Chapter 6 Learning - WW Norton & Company

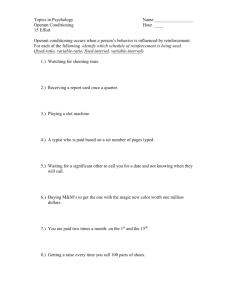

advertisement

6.1 What are the three ways we learn? 6.2 How do we learn by classical conditioning? Ch. 6 Learning 6.4 How do we learn by watching others? 6.3 How do we learn by operant conditioning? 6.1 What Are the Three Ways We Learn? • Learning: a relatively enduring change in behavior due to experience – Central to almost all areas of human existence We Learn From Experience • Behaviorism: a formal learning theory from the early twentieth century – John Watson: focused on environment and associated effects as key determinants of learning – B. F. Skinner: designed animal experiments to discover basic rules of learning We Learn From Experience • Critical for survival • Adapt behaviors for a particular environment – Which sounds indicate potential danger? – What foods are dangerous? – When is it safe to sleep? We Learn in Three Ways 1. Non-associative learning 2. Associative learning 3. By watching others • Let’s look at these on the following slides We Learn in Three Ways 1. Non-associative learning: information about one external stimulus (e.g., a sight, smell, sound) We Learn in Three Ways • 1a. Habituation: exposure to a stimulus for a long time, or repeatedly, leads to a decrease in behavioral response – Especially if the stimulus is neither harmful nor rewarding • See Figure 6.2a on the next slide . . . We Learn in Three Ways We Learn in Three Ways • 1b. Sensitization: exposure to a stimulus over a long time, or repeatedly, leads to an increase in behavioral response – Heightened preparation in a situation with potential harm or reward • See Figure 6.2b on the next slide . . . We Learn in Three Ways We Learn in Three Ways • 2. Associative learning: understanding how two or more pieces of information are related We Learn in Three Ways • 2a. Classical conditioning: learn that two stimuli go together – Example: music from scary movies elicits anxiousness when heard • 2b. Operant conditioning: learn that a behavior leads to a particular outcome – Example: studying leads to better grades We Learn in Three Ways • 3. Learning by watching others – Observational learning – Modeling – Vicarious conditioning The Brain Changes During Learning • Long-term potentiation (LTP): the strengthening of synaptic connections between neurons – Recall that “cells that fire together, wire together” – Exposure to environmental events causes changes in the brain to allow learning 6.1 What are the three ways we learn? 6.2 How do we learn by classical conditioning? Ch. 6 Learning 6.4 How do we learn by watching others? 6.3 How do we learn by operant conditioning? 6.2 How Do We Learn By Classical Conditioning? • Familiar example: association between scary music in movies and bad things happening to characters Through Classical Conditioning, We Learn That Stimuli Are Related • Pavlov: Nobel Prize in 1904 for research on the digestive system • Observed dogs began to salivate as soon as they saw bowls of food – Salivating at sight of a bowl is not automatic – Behavior acquired through learning by association • See Figure 6.3b on the next slide . . . Through Classical Conditioning, We Learn Stimuli Are Related Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Classical conditioning: learning begins with a stimulus that naturally elicits a response – Much like a reflex Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Four key steps: 1. Present unconditioned stimulus: evokes unlearned response 2. Present neutral stimulus: no response 3. Pair stimuli from Steps 1 and 2: learned response (conditioning trials) 4. Neutral stimulus alone will trigger learned response (critical trials) • Let’s look at this on the next slide Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Step 1: presenting food causes salivary reflex – Unconditioned stimulus (US): nothing is learned about the stimulus (e.g., food) – Unconditioned response (UR): an unlearned behavior, like a simple reflex (e.g., salivation) Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Step 2: clicking metronome is neutral stimulus – Neutral stimulus: anything seen or heard; must not associate with the unconditioned response Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Step 3 (conditioning trials): start of learning – Dog begins to associate US (food) and neutral stimulus (metronome) Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Step 4 (critical trials): association learned – Metronome alone, without food, makes dog salivate • See Figure 6.3 on the next slide . . . Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning Pavlov’s Experiments Reveal the Four Steps in Classical Conditioning • Conditioned stimulus (CS): after conditioning, previously neutral stimulus (NS) reliably produces unconditioned response (UR) • Conditioned response (CR): behavior only after conditioning; usually weaker than unconditioned response Learning Varies in Classical Conditioning • Animals adapt via conditioning • Learning to predict outcomes leads to new adaptive behaviors Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery • Acquisition: gradual formation of learned association between CS and US to produce CR – Strongest conditioning occurs when CS is presented slightly before US • See Figure 6.5a on the next slide . . . Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery • Extinction: CS no longer predicts arrival of US • Sometimes associations are no longer adaptive • See Figure 6.5b on the next slide . . . Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery • Spontaneous recovery: original association between CS and US is relearned • Can occur after only one pairing following extinction – Response will get weaken if CS-US pairings do not continue • See Figure 6.5d on the next slide . . . Acquisition, Extinction, and Spontaneous Recovery Generalization, Discrimination, and Second-Order Conditioning • Stimulus generalization: stimuli similar, but not identical to, CS that produces CR – Animals respond to variations in CS • See Figure 6.6 on the next slide . . . Generalization, Discrimination, and Second-Order Conditioning Generalization, Discrimination, and Second-Order Conditioning • Stimulus discrimination: differentiate between similar stimuli; one is consistently associated with US and the other is not • See Figure 6.7 on the next slide . . . Generalization, Discrimination, and Second-Order Conditioning Generalization, Discrimination, and Second-Order Conditioning • Second-order conditioning: second CS becomes associated with first CS; elicits CR when presented alone • Neither US nor original CS present – Example: pairing black square (second CS) with metronome (first CS) so black square produces salivation (CR) on its own We Learn Fear Responses Through Classical Conditioning • Phobia: acquired fear that is very strong in comparison to threat The Case of Little Albert • Classical conditioning demonstrated in phobias: – Showed “Little Albert” various neutral objects (e.g., white rat, rabbit, dog, monkey, white wool) – Paired rat (CS) and loud clanging (US) until rat alone produced fear (CR) • Fear generalized to all similar stimuli • See Figure 6.8 on the next slide . . . The Case of Little Albert Counterconditioning • Classical conditioning techniques valuable in treating phobias Counterconditioning • Counterconditioning: exposing subject to phobia during an enjoyable task • Systematic desensitization: exposure to feared stimulus while relaxing – CS -> CR1 (fear) connection replaced with CS -> CR2 (relaxation) connection Adaptation and Cognition Influence Classical Conditioning • Pavlov’s belief: any two events presented together would produce learned association • By 1960s, data suggested that some conditioned stimuli more likely to produce learning Evolutionary Influences • Certain pairings more likely to be associated – Conditioned taste aversions: easy to produce with smell or taste cues – Auditory and visual stimuli: value for signaling danger Cognitive Influences • Through classical conditioning, animals predict events – Easier when CS before US rather than after US – Easier when CS is more unexpected or surprising 6.1 What are the three ways we learn? 6.2 How do we learn by classical conditioning? Ch. 6: Learning 6.4 How do we learn by watching others? 6.3 How do we learn by operant conditioning? 6.3 How Do We Learn by Operant Conditioning? • Human behaviors are purposeful • Operant conditioning: relationship between behavior and consequences We Learn Effects of Behavior Through Operant Conditioning • Operant conditioning: animals operate on environments to produce effects • Consequences determine likelihood of behavior in future Thorndike’s Experiments Reveal the Effects of Action • Thorndike’s puzzle box: challenged fooddeprived animals to find escape – Trap door would open if animal performed specific action – Animal quickly learned to repeat behavior to free itself and reach the food • See Figure 6.10 on the next slide . . . Thorndike’s Experiments Reveal the Effects of Action Thorndike’s Experiments Reveal the Effects of Action • Thorndike’s general theory of learning – Law of effect: any behavior leading to a “satisfying state of affairs” likely to be repeated – Any behavior leading to an “annoying state of affairs” less likely to reoccur Learning Varies in Operant Conditioning • B. F. Skinner’s learning theory based on the law of effect: – Reinforcer: stimulus occurs after response and increases likelihood of response reoccurring • Believed that behavior occurs because reinforced Shaping • Shaping: operant-conditioning technique; reinforce behaviors increasingly similar to desired behavior • See Figure 6.12 on the next slide . . . Shaping Reinforcers Can Be Conditioned • Primary reinforcers: satisfy biological needs, necessary for survival (e.g., food, water) • Secondary reinforcers: serve as reinforcers, do not satisfy biological needs; established through classical conditioning Reinforcer Potency • Some reinforcers are more powerful • Premack principle: more valued activity can reinforce performance of less valued activity – Example: “Eat your spinach and then you’ll get dessert.” Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Operant Conditioning • Reinforcement and punishment have opposite effects on behavior – Reinforcement: behavior more likely to be repeated – Punishment: behavior less likely to occur again Positive and Negative Reinforcement • Both positive and negative reinforcement increase likelihood of a given behavior Positive and Negative Reinforcement • Positive reinforcement: addition of stimulus that increases probability behavior will reoccur – Example: feeding a rat after it has pressed a lever • Negative reinforcement: removal of stimulus that increases likelihood of given behavior – Example: taking a pill to get rid of a headache Positive and Negative Reinforcement • Both positive and negative punishment reduce likelihood that behavior will be repeated Positive and Negative Reinforcement • Positive punishment: addition of stimulus decreases probability of behavior being repeated – Example: electrical shock, speeding ticket • Negative punishment: removal of stimulus decreases probability of behavior being repeated – Example: loss of food, loss of privileges Schedules of Reinforcement 1. Continuous reinforcement: behavior reinforced each time it occurs – Fast learning, uncommon in real world 2. Partial reinforcement: behavior is occasionally reinforced – More common in real world Schedules of Reinforcement • How reinforcement given x how consistently given = four common schedules 1. 2. 3. 4. Fixed schedule: predictable basis Variable schedule: unpredictable basis Interval schedule: based on passage of time Ratio schedule: based on number of responses • See Figure 6.15 on the next slide . . . Schedules of Reinforcement Schedules of Reinforcement 1. Fixed interval schedule (FI): reinforcement after fixed amount of time – Example: paycheck 2. Variable interval schedule (VI): reinforcement after unpredictable amount of time – Example: pop quiz – More consistent response rates than fixed interval Schedules of Reinforcement 3. Fixed ratio schedule: reinforcement after fixed number of responses – Example: paid by the completed task – Often yields better response rates than fixed interval 4. Variable ratio schedule: reinforcement after variable number of responses – Example: slot machine Schedules of Reinforcement • Partial-reinforcement extinction effect: behavior lasts longer under partial reinforcement than under continuous reinforcement • To condition behavior to persist: – Use continuous reinforcement initially – Slowly change to partial reinforcement Operant Conditioning Affects Our Lives • Imagine a parent says no to a candy bar, so child throws a tantrum – Parent yells, “If you don’t stop screaming, you’re going to get a smacked bottom!” • Will this approach get the desired behavior? Parental Punishment Is Ineffective • To be effective, punishment must be: – Reasonable – Unpleasant – Applied immediately – Clearly connected to the unwanted behavior Parental Punishment Is Ineffective • Punishment can cause confusion: – Wrongly applied after desirable behavior – Leads to negative emotions (e.g., fear, anxiety) – Fails to offset reinforcing aspects of the undesired behavior • Reinforcement teaches desirable behavior • See Figure 6.16 on the next slide . . . Parental Punishment Is Ineffective Behavior Modifications • Behavior modification: operant conditioning replaces unwanted behaviors with desirable behaviors • Most unwanted behaviors can be unlearned Behavior Modifications • Token economies: opportunity to earn tokens (secondary reinforcers) for completing tasks and lose tokens for behaving badly – Tokens later traded for objects or privileges • Gives participants sense of control Biology and Cognition Influence Operant Conditioning • Behaviorists believed conditioning principles explained all behavior • In reality, reinforcement explains only a certain amount of human behavior Dopamine Activity Affects Reinforcement • Biological influence on how reinforcing something is – Drugs that block dopamine’s effects disrupt operant conditioning – Drugs that enhance dopamine activation increase reinforcing value of stimuli Biology Constrains Reinforcement • Some animal behaviors hardwired – Difficult to learn behaviors counter to evolutionary adaptation • Conditioning most effective when matched to animal’s biological predispositions Learning Without Reinforcement • Tolman argued that reinforcement impacts performance more than knowledge acquisition – Ran rats through complex mazes to obtain food – Cognitive map: maze-specific mental representation that Tolman believed each rat developed Learning Without Reinforcement • Three groups of rats traveled maze – Group 1: no reinforcement – Group 2: reinforcement every trial – Group 3: reinforcement only after first 10 trials • See Figure 6.19 on the next slide . . . Learning Without Reinforcement Learning Without Reinforcement • Latent learning: learning without reinforcement • Group 1: slow, many wrong turns • Group 2: faster, fewer errors each trial • Group 3: – Before reinforcement, similar to Group 1 – After reinforcement, better than Group 2 Learning Without Reinforcement • Insight learning: solution suddenly emerges after delay; type of problem solving • Reinforcement does not fully explain but predicts behavior’s repetition 6.1 What are the three ways we learn? 6.2 How do we learn by classical conditioning? Ch. 6: Learning 6.4 How do we learn by watching others? 6.3 How do we learn by operant conditioning? 6.4 How Do We Learn by Watching Others? • Behaviors we learn by watching others: – Mechanical skills, social etiquette, situational anxiety, attitudes about politics and religion • Three ways we learn by watching: 1. Observational learning 2. Modeling 3. Vicarious conditioning Three Ways We Learn Through Watching 1. Observational learning: individual acquires or changes behavior after viewing it at least once – Examples: foods safe to eat, objects and situations to fear • Powerful adaptive tool • See Figure 6.20 on next slide . . . Three Ways We Learn Through Watching Bandura’s Research Reveals Learning Through Observation • Observation of aggression: Bandura’s Bobo doll study – Group 1: watched film of adult playing quietly with Bobo, an inflatable doll – Group 2: watched film of adult attacking Bobo • Viewers of aggression were more than twice as likely to play aggressively Learning Through Modeling 2. Modeling: imitation of observed behavior • More likely to imitate actions of attractive, high-status models similar to ourselves • See Figure 6.22 on the next slide . . . Learning Through Modeling Learning Through Vicarious Conditioning 3. Vicarious conditioning: learning about consequences by watching others – Rewarded behavior more imitated – Punished behavior less imitated • See Figure 6.23 on the next slide . . . Learning Through Vicarious Conditioning Watching Others Results in Cultural Transmission • Meme: shared piece of cultural knowledge – Similar to genes, selectively passed across generations, can spread much faster – Animals also show this kind of knowledge sharing • See Figure 6.24 on the next slide . . . Watching Others Results in Cultural Transmission Biology Influences Observational Learning • Mirror neurons: fire in your brain and other person’s brain every time you watch them engaging in an action – Does not always lead to imitation • Scientists still debating mirror neurons’ function