File

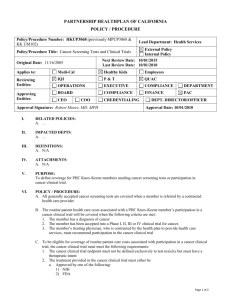

advertisement