Link

advertisement

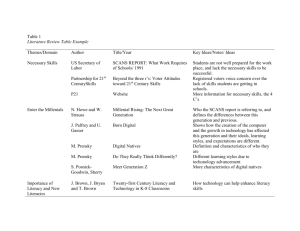

Running Head: LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN Navigating educational reforms: Reflections on stimulating literate student agency in the economic domain George L. Boggs Florida State University email: glboggs@fsu.edu phone: (850)644-4880 fax: (850)644-7736 Hilda E. Kurtz The University of Georgia email: hkurtz@uga.edu LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 2 Abstract This paper grounds 21st century literacy instruction economically. Abstract and workforce preparation oriented economic rationales for 21st century literacies create a domain for curriculum research on social, especially economic, significance of student action, but reform narratives lack economic rationales for designing literacy instruction. Using sociocultural theories of language and social practice, we characterized student projects in five iterations of a service-learning course by their degree of connection (networked or insulated) to systems of economic exchange and their manner of participation (direct or mediated) in economic activities. We found that service-learning students embraced a wide variety of organizational and communicative means to accomplish required and student generated projects; within each semester, projects tended to increase in connectedness to networks of economic exchange and increase slightly in directness of participation in production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. While each course include what one student referred to as “typical academic activities,” characterized as insulated and mediated with respect to economic life, students working together with the support of disciplinary concepts demonstrated economically significant literacy-supported agency in the economic domain. These findings confirm the importance of authentic learning experiences and underline the need for careful interpretation of economic narratives underpinning educational reform. Keywords: 21st century literacies, economics, disciplinary literacies, educational reform, funds of knowledge 2 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 3 “The distortions of our language help make us helpless” (Sharp, 2011, n.p.). In Gulliver’s Travels (2009/1726-7), Swift’s professors portray frivolous academia through their inane research efforts to improve literacy and the food system— the most developed episode incorporates both at once. Touché! say the literacy and local food researchers. The fatuous linguist sought to revolutionize literacy by having folks carry the things themselves like sheep and England instead of words and sounds; his stuffy and unfeasible response to the complex intersections of language, politics, and economics is meant to amuse. The joke—that language is transcendently efficient, indispensible for its ability to symbolize abstractly—has a double edge, for language and even thinking are entangled economically. Well into Swift‘s lifetime, world powers enriched themselves through mercantile trade restrictions: Raw materials in, manufactured goods out; silver and gold in, never out. Read in the context of mercantilism past its prime, Swift’s satire combines the interconnectedness of literacy and economic existence with the unwillingness of researchers to get real about it. Economic abstractions backed up by employers’ pleas for skilled writers and problem solvers are currently driving educational reform in the research gap between new means of communication and economically relevant literacy instruction. “Magical thinking” (Labaree, 2012) about this convergence of economy and education ultimately leaves teachers holding the bag—to design instruction “for jobs that do not yet exist” (Dede, 2010). In response, this paper situates literacy practices in the context of emergent economic realities to foster relevant curriculum design decisions (Rutkowski, Rutkowski, & Langfelt, 2011). Swift pilloried the destructive consequences for humans, animals, and nature of an economic system past its prime, and he lamented sorry institutional efforts to adjust. High status educational reform imperatives today shape and are shaped by the financialization of higher education, a shift in emphasis toward returns on investment at the expense of other measurements of productivity (Au, 2011). A key critical agenda is therefore to respond to and accommodate high status educational reform narratives in a way that positions teachers and students to resist the economic and social forces from which the reform imperatives emanate (21st Century Schools, 2010; Laitsch, 2013). This paper reports on our efforts to do so in the context of a service-learning course centered 3 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 4 on food justice. In the course, we draw attention to the problem of communication, strategy, and seeking justice among multiple stakeholders with a variety of expectations, while a significant fraction of our audiences—the public, the state and federal government, and the university—becomes increasingly fixated on economic growth. The need to navigate these tensions highlights conundrums with language a la Gulliver’s Travels, and spurs critical reflection on the economic relevance of 21st century literacies. It is not hard to offer economic competitiveness for labor markets as a rationale for educational reform, but an abstract crisis narrative like global competition needs to be unpacked (Voogt & Roblin, 2012). In this paper, we discuss a theoretical basis for economically-minded literacy education and describe our method of researching the economic significance of student work in a series of service-learning courses. We then evaluate student work in light of core dimensions of economic participation, relation to networks of exchange and manner of engagement in economic activity. A relationship between economic relevance of coursework and the development of 21st century literacies is examined as a way of thinking about current instructional practices. We engage these issues in hopes of probing and reconciling contradictions inherent in powerful economic metanarratives currently asserting such control over educational practice. As we endeavor to ‘get real’ about the interconnectedness of literacy and (21st century) economic existence, we invite questioning of our motives, process, and conclusions. 21st Century Literacies 21st century literacies described by the National Council of Teachers of English (2013, Figure 1) and closely related to 21st century competences and skills identified in literally thousands of publications annually emphasize the ability to collaborate and solve problems rather than the possession of a static body of knowledge (Voogt & Roblin, 2012). Likewise, open-ended preparation for a workforce of possibility is prized over vocational training or disciplinary specialization (Dede, 2010). Reform advocates point to many types of dysfunction as the impetus for changing literacy education, most often the mismatch between school learning and workforce needs (Kay, 2008; Kellner, 2000; P21.org, 2011). Nationalistic rationales for improving literacy education warn of losing a competitive edge to eager outsiders in a global market, while global development models 4 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 5 use free market rationales to argue for the common good. However, free market rationales for 21st century literacies education mask the emergence of a transnational neomercantile system in which concentrated wealth and concentrated political power mutually support one another at the expense of consumers, producers, and distributors of goods and services (Labaree, 2012). The effect on education is that abstract economic models supplant other models of productivity. For teachers, there is intense pressure to build and update literacy instruction out of blind faith in a connection between literacy and the economy. The economic anti-rationale will breed resistance; what’s worse is it offers little guidance for fostering literate student agency. -------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here -------------------------While contemporary literacy practices recognizably respond to technological changes in the way information is created, communicated, enhanced, and put to use, and might seem to embrace the democratization of knowledge production, such commitments are belied by the free-market rationales used in support of 21st Century Literacies, The Partnership for 21st Century Schools, and the Common Core State Standards Initiative (P21.org, 2011; CCSI, 2012; Voogt & Roblin, 2012). Economic thinking that motivates 21st century skills reform does not practically embrace the depth of the paradigmatic changes brought on by soaring food costs, climate change, unemployment, and austerity measures worldwide. Likewise, seemingly cutting-edge return-on-investment models, tied invariably to test scores, graduation rates, or employment, are inarticulate with respect to literacy instruction (Voogt & Roblin, 2012), often reinforcing antithetical teaching practices (Au, 2011). The problem for developing instruction around these new literacy and economic practices is formidable. First, economic changes are continually demanding new modes of interacting, so it is fruitless merely to “train” students in the use of the latest communication gadgets. Second, economic changes go deeper than changes in the constitution of the global workforce; the housing crisis, blended consumerism, and social activism, and local food movements are only a few areas in which radical economic change bursts the labor market paradigm for curriculum design. Third, like new wine in 5 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 6 old wineskins, the policies underwriting contemporary structural change in secondary and post-secondary education originate in archaic models of workforce preparation rather than emergent economic life (Duff, 2008). Literacy education cannot be evaluated solely by the likelihood of getting some child some job someday, and it cannot be graded based on students’ use of internet communicative tools (Hennessy, Ruthven, & Brindley, 2005). Economic environments that literacies help create and transform should figure in as well. This paper explores ideas about what we can do as instructors to stimulate literate student agency in the economic domain beyond workforce development. Our goal is to step back with the bigger economic picture in mind, and consider the manipulation of local economic environments as a fundamental property of literate life in the 21st century. To accomplish this larger goal we accept the premise that literacy practices and even thinking are part of economic reality, and, since we cannot fulfill our responsibility as teachers merely by training our students for a known workforce, we seek to understand the emergent, local, economic consequences of 21st century literacies in the context of school-based learning. Theoretical Framework Critical Funds of Knowledge This paper employs the foundational notion of language as a cultural tool from Vygotskian (1987) sociocultural theory to recognize opportunities for mutual assistance between school and community. People’s literacy signifies “ability to use literary skills to manipulate their environment efficiently and productively” (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005, p. 65). Outside of school, literacies—flexible sets of culturally situated resources—are deployed every day in ways that affect local economic security. This study focuses on community development opportunities originating in school, supported by the resources of a discipline, instructor, and others, and schematizes the economic significance of students’ major activities that make up a university service-learning course. The notion of situated literacies (Barton & Papen, 2010) has been used to show that literacies are economically embedded social practices that serve people’s day-to-day needs. As they worked to bring about change on behalf of working poor US-Mexican 6 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 7 families, González, Moll, and Amanti (2005) accepted that literacy education is good because it offers people entrée into formal employment in primary labor markets (p. 58), but they also recognized that economic activity goes far beyond participation in labor markets. Literacy education can be good for a million other reasons, many clustered around improved community economic stability. Affordances and constraints This analysis of 21st century literacies in an academic discipline focuses on the economic significance of student activity in a course. The research is rooted in the notion that tools such as language and communicative technologies have actual and perceived affordances and constraints (Gibson, 1979). An affordance describes a potential for action posed by objects, the potential for harnessing objects such as technologies for our assertive will (Ryder & Wilson 1996). Constraints refer to the real or perceived limitations on the use of an object for a given purpose. Here, we use affordances and constraints in relation to literacies as well as the communication technologies associated with them. For example, writing online affords communicating across geographical and some temporal boundaries, while writing on a tree trunk affords transcendence of temporal boundaries yet constrains global sharing. Social media tools afford distribution of a photograph of the otherwise bounded inscription to millions. 21st Century Literacies and skills education privileges the literate use of multiple, changing communicative technologies because of their affordances for participation in emergent social networks with vast potential for economic impact. Teachers often struggle to align students’ low view of the affordances of literacy (e.g., toil, wasting time, winning tokens of school success) with its potential (e.g., persuading, contributing to public discourse, advertisement). Limited literacy constrains action as suggested by the expression “when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” With acquisition of a more robust literacy comes the ability to perform actions afforded by the literacy’s tools. We proceed from the premise that literacy practices shape and are shaped by economic conditions and relations; that is, among actions afforded by literacy is the ability to respond to and shape economic conditions. We define literate student agency, then, as the ability to select and use symbolic systems strategically to manipulate an environment. Our task is thus to examine the role of 7 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 8 literacy in helping students identify relevant environments to manipulate and relevant tools with which to manipulate them as they respond to economic vulnerabilities and opportunities. Students in our study were attempting to respond to locally experienced economic vulnerabilities by supporting the local food movement and increasing access to quality, affordable food. To that end, we drew students’ attention to the problem of communication, strategy, and seeking justice among multiple stakeholders. Economic impact analysis Examining the ways in which 21st century literacies afford students’ participation in and manipulation of local food economies offers a way to inscribe locally sustainable instructional directives into the global competition imperatives that underpin 21st century educational reform. In the following analysis, we plot course activities according to schematized economic properties, asking how directly student actions relate to the conditions of local food access and to what degree they are mediated by institutional or other apparatuses? In other words, are student activities insulated from (economic/food access) conditions in the local communities, or are they networked with/among other stakeholders? Do student activities directly produce economic goods and services, or is their economic participation indirect? This analysis does not put a dollar amount on economic impact of student activities. The value of the analysis is in schematizing economic engagement and integrating economic thinking into 21st century literacies education. We suggest that such an analysis reveals more about curricula than typical return on investment calculations based on graduation rates (e.g., Communities in Schools, 2012). Method Context Local food system. Renewed interest in local food systems as social contexts, labor markets, objects of study, and means of social change and protest has sparked the development of food-oriented courses in various departments and colleges within the university where this research is being conducted. The town boasts a vibrant local food system, but participation appears to be very uneven in terms of the socioeconomic backgrounds. In recognition of the broader implications of a food system beyond farmers’ markets and restaurants with local offerings, instructors and students in human geography 8 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 9 developed a course aimed at addressing food system disparities through an ethic of mutual aid. Course. The course invited students to read about suffering caused by paternalistic and unilateral solutions to poverty and hunger as a basis for developing ideas about mutually supported community action. The course was designed in 2007 as a servicelearning based intervention in disparate access to healthy and affordable food within/across the local community. The course creates an opportunity for students to engage critically with problems of hunger and food insecurity in the community through group service learning projects supported by discussion-based academic work and reflective writing. In 2011, the course was incorporated into a food studies-related certificate program that provides a strong suite of courses and numerous service learning and internship opportunities to position students to contribute to the development of vibrant alternative food initiatives (Allen, et al. 2003). The course, taught five times during the study, was focused on community engagement to increase access to affordable, healthy food. The Urban Food Collective (UFC) adopted the motto “Direct learning through direct action.” The course satisfied majors’ and instructors’ intention to have an experiential course on food issues in human geography, with a focus on structural change, as opposed to charitable food relief services such as soup kitchens. Students were invited to read about global and local food insecurity, about how food relief programs perpetuated local instability, and about the importance of avoiding paternalistic approaches to community development. Participants. Three course instructors, who took turns, approached the course and local community engagement with different syllabi, philosophical positions, and prior experience. They agreed on the necessity of students deciding how, why, and with whom to engage. Thirty-five student participants included 50% human geography majors, 5% graduate students. Students were typically in their second year or beyond, and most described themselves as successful in school. Data Physical artifacts of student work included documents, photographs, field notes, and publicity generated by participants and press agencies. Syllabi from the UFC courses were collected as well as syllabi from food-related traditional format courses. Study 9 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 10 participants, with six exceptions, provided initial and exit interviews. Classroom discussions and select meetings outside class were audio recorded and transcribed. These data enabled us to identify and characterize student action, the major projects that students undertook. Each semester’s projects (Figure 2) could then be categorized in relation to economic development characteristics and later examined with respect to the affordances and constraints of 21st century literacies. -------------------------------Insert figure 2 about here -------------------------------Analysis. We subjected the student projects that made up each UFC course to schematic economic analysis. The diagram below (Figure 3) represents economic activity visually, as an aid in thinking about desirable educational goals and experiences. Figure 3 shows an economic conceptualization of course projects in terms of two key dimensions. Course projects were categorized with respect to their connectedness to exchange markets and the directness of their economic activity. Student projects were deemed either insulated from or networked to exchange contexts and either directly producing, distributing, or consuming goods and services or affecting economic activity in highly mediated ways. We further distinguished the categories by low and high degree. Working clockwise from the top around Figure 3, for direct economic activity, the scale of production could be small or large. For networked actions, low and high connectedness was determined according to the necessity of the network to the action. Mediated, indirect economic participation was subdivided again into the large or small scale of influence. More and less insulated actions were distinguished by avoidance of networking versus exercises in connectedness nonetheless separated from networks beyond the classroom. ------------------------------Insert figure 3 about here ------------------------------Course initiatives (UFC I-V) were plotted in relation to the two axes and in terms of their degree, high and low (Figure 4). Such visualization affords examination of the 10 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 11 role of 21st century literacies and reflection upon the economic significance of other courses we teach. An Economic View of Student Action Plotting course activities according to their economic properties reveals economic impact of curricula at a finer, more informative resolution compared with return on investment calculations based on graduation rates (e.g., Communities in Schools, 2012). Activities in the courses transcended the domain of typical school activities, whose economic value is too often restricted to the lower left quadrant, that is, insulated and highly mediated in terms of economic participation.1 Moreover, within each of the five iterations of the UFC course is a progression over time from insulated, mediated action toward a combination of direct and mediated networked action, with a general movement from left to right. -----------------------------Place Figure 4 about here --------------------------------------------------------Place Figure 5 about here ----------------------------------------------------------Place Figure 6 about here -----------------------------21st century literacies and economic relevance A graph of UFC I-V action provides an opportunity to understand the role of 21st century literacies in the courses’ economic significance (Figure 8, above), and to grasp why “new literacies are central to full civic, economic, and personal participation in a global community” (International Reading Association, 2009). Technologically literate communication permeated even the most traditional forms of classroom activity. Many students accessed digital copies of required readings. Discussions of readings were 1 It is instructive to note how commonly schools coercively position students economically (e.g., as consumers of textbooks, producers of fundraising revenue) while schooling rarely positions students as agentive producers for audiences beyond the classroom. A notable exception is Uzbek public education, where students are required annually to harvest cotton by hand. 11 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 12 enriched, from time to time, by popular culture references, acknowledgements of contributions from other fields, and media representation of issues. Discussions were periodically interrupted by requests for web links, listserv addresses, online documents, and phone numbers. However, students observed a threshold in class meetings that corresponds with analysis of economic significance: Discussion of readings gave way, within each class meeting and from beginning to end of each semester, to discussion of community engagement. In UFC II, a massive community food assessment project eclipsed the readings for several weeks. Late in semesters I, IV, and V, the instructor placed discussions at the end of class in order to allow necessary time for course projects. In this way, what one student described as “typical academic activities" (i.e., reading, discussion, and writing) faded into the background over time, while 21st century literacies became indispensable to student projects. While the courses placed a premium on student ownership of their learning, and thus, indirectly, on the literacies that make less-hierarchical collaborative learning possible, the application of 21st century literacies to the problems in question pushed economic significance of initiatives toward networks of interested parties, a major concern of Common Core State Standards for literacy (CCSSI, 2012) Literacies and economically significant action intersected in the engagementoriented course format, a phenomenon represented with some irony in Jairus’ account of writing an article for a newspaper in UFC IV: Well my part [of the article] was the last section, right before we asked people to come to [the activist networking session]. [Pause] This class was one of my favorites. Going to miss this class. I don’t want to put any dirt on [UFC III], but this class was a lot better. We were not so much in the books, but in the community trying to get stuff done. Contrasting conceptualizations of traditional school literacy throw light on the affordance of 21st century literacies (e.g., identifying stakeholders, building networks, communicating purposively) for extending economic impact. In fact the article he helped write put him in the community in a way that he had never experienced before, even in a prior UFC course. The point is that as students and policymakers increasingly demand authentic, useful capabilities as the end goal of education, the affordances and constraints 12 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 13 of literate practices must be evaluated in ways that connect learners with the environments their literacy enables them to manipulate. Discussion Course actions identified in Figure 1 required participants to negotiate among many approaches to a problem. The occurrence of most of those initiatives late in each semester, together with the rushed way that many wound up taking place, suggests a thread interweaving unstructured tasks, ‘real-world’ problems, and the opportunity and pressure to do something of lasting value locally. Networked, mediated economic activity evident in community outreach efforts depended heavily on 21st century literacies, as sets of tools helping participants and community members understand and act in response to the problem of food insecurity. “Typical school activities” like writing papers and discussing readings should not be valued less because they are less directly involved and networked with economic structures, but economic analysis can help describe the artificial limitations teachers and schooling often place on students. Economically isolated and mediated projects are often transformed as 21st century literacies reposition the classroom as a staging area for purposive interactions that bridge school and community concerns. Unfortunately, school often remains a kind of dry swim: a highly abstract, tenuous, and unfocused setting in which what students produce or exchange has little value beyond classroom or school. Nonetheless, our economic evaluation constructs action whose economic impact is insulated and mediated as a potentially vital transitional phase. The left to right and bottom to top economic movement we tracked in each semester demonstrates the potential and importance of using typical academic activities as a research and development phase rather than permanent state of isolation. It may be hard to envision the widespread reification of school as un-real, but a graduate student participant offered a glimpse of the scope of the problem when he reported radical differences in community reception to his ideas depending on whether he identified himself as a student or member of a community action organization. His youth didn’t matter. His network did. Figure 6, above offers one explanation for why community members expect little from students in school. Fundamentally, Internet communicative tools blur the division between novice children and competent adults when it comes to a) community participation and b) 13 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 14 collective action. These accompanying literacies enable them to manipulate their worlds with a range of potential for impact, including economic growth. Economic development in this study consists mainly of expanding the local food system, which has been shown to correlate significantly with increased local employment and personal income (Martinez, et al, 2010). Complementary factors, such as health, nutrition, reduced crime, and community solidarity have been similarly related. Educators and researchers need to develop strategies for understanding how actions, and even thinking, are embedded in economic systems. One participants’ response to a peer’s question concerning vegetable varieties encapsulates this need: Aaron said, “I thought it was interesting how you express your fathers’ position that commonly available varieties of tomatoes served their purposes, but whose purposes, why?” Aaron’s question might be evaluated positively from a range of disciplinary perspectives due to its awareness of bias and critical thinking. Too often, the goal of academic disciplines to serve the common good is needlessly sacrificed to the project of showing students the ropes. Aaron’s question was shaped by his internalization of disciplinary concepts of scale, food system, commodity food, logistics, and marketing. His literacies in Global Information Systems (GIS) technology and multiple communicative platforms enabled him not only to pretend in school with authentic realworld problems, but to feed information to local food activists, speak to city commission members, build restaurant networks to support local farmers, and write for the paper. Far from treating economic development as an unquestioned good, however, drawing attention to economic significance available through school settings environments offers a unique opportunity to put flesh on the disembodied economic imperatives driving secondary literacy instruction. A critical funds of knowledge approach enables us to ask Which economy, whose growth, and whose security does the acquisition of 21st century skills and literacies benefit? Whose goals are served by global competition in labor markets? The findings of this research confirm the importance of 21st century literacies, but they represent a challenge to global competition as the reason for employing them. The scale at which we choose to view economic development matters a great deal to the vitality of communities and households, and, as demonstrated here, the potential for 21st century literacies education. 14 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 15 15 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 16 References 21st Century Schools (2010). What is 21st century education? Retrieved from http://www.21stcenturyschools.com/What_is_21st_Century_Education.htm Au, W. (2011). Teaching under the new Taylorism: High-stakes testing and the standardization of 21st century curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(1), 25-45. Barton, D. & Papen, U. (Eds.) (2010). The Anthropology of writing: Understanding textually-mediated worlds. London: Continuum. Communities in Schools (2012). The economic impact of Communities In Schools: An economic impact quantifying the costs and benefits of Communities In Schools model. Retrieved from http://www.communitiesinschools.org/about/publications/publication/economicimpact-communities-schools. Dede, C. (2011). Reconceptualizing technology integration to meet the challenges of educational transformation. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 5(1), 4-16 Duff, A. (2008). The Normative Crisis of the Information Society. Cyberpsychology : Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 2(1). Engeström, Y. (2004). New forms of learning in co-configuration work. Journal of Workplace Learning 16(1/2), 11-21. Framework for 21st century learning (P21) (2011). Retrieved from http://www.p21.org/overview Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin. González, N., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Hennessy, S., Ruthven, K., & Brindley, S. (2005). Teacher perspectives on integrating ICT into subject teaching: commitment, constraints, caution, and change. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(2), 155-192. Howard, R. M. (2000). Collaborative pedagogy. In G. Tate. A Rupiper, & K. Schick (Eds.), Composition pedagogies: A bibliographic guide, 54-71. New York: Oxford University Press. 16 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 17 International Reading Association (2009). New literacies and 21st century technologies: A position statement of the International Reading Association. Retrieved from http://www.reading.org/Libraries/position-statements-andresolutions/ps1067_NewLiteracies21stCentury.pdf Kay, K. (2008). Ken Kay, president of the partnership, provides platform testimony for the DNC and RNC. Retrieved from http://www.p21.org/events-aamp-news/pressreleases/488-ken-kay-president-of-the-partnership-provides-platform-testimonyfor-the-dnc-and-rnc Kellner, D. (2000). New technologies/new literacies: Reconstructing education for the new millennium. Teaching Education, 11(3), 245-265. Laitsch, D. (2013). Smacked by the invisible hand: the wrong debate at the wrong time with the wrong people. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(1), 16-27, DOI: 10.1080/00220272.2012.754948 Martinez, S., Hand, M. Da Pra, M., Pollack, S, Ralston, K., Smith, T., Vogel, S. (2010). Local food systems: Concepts, impacts, and issues. Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/122864/err97_reportsummary_1_.pdf National Council of Teachers of English Executive Committee (NCTE) (2013). The NCTE definition of 21st century literacies. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/21stcentdefinition Professional development for the 21st century (P21) (2013). Retrieved from www.p21.org/storage/documents/ProfDev.pdf Rutkowski, D. Rutkowski, & Langfelt, G. (2011). Smacked by the invisible hand. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(2), 165-192. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00220272.2011.586728 Ryder, M., & Wilson, B. G. (1996). Affordances and constraints of the internet for learning and instruction. Paper presented at Association for Educational Communications Technology (AECT). Retrieved from http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~mryder/aect_96.html. Sharp, G. (2011). Sharp's dictionary of power and struggle. New York, NY: Oxford. 17 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 18 Swift, J. (2009/1726-7). Gulliver’s travels into several remote nations of the world. Project Gutenberg Ebook. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/829/829-h/829-h.htm Voogt, J. & Roblin, N. P. (2012). A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21st century competences: Implications for national curriculum policies. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(3), 299-321. Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In R. Rieber & A. Carton, Eds; N. Minick, Trans., Collected works, vol. 1, 39-285. New York, NY: Plenum. 18 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 19 Figures Figure 1. National Council of Teachers of English Definition of 21st Century Literacies Active, successful participants in this 21st century global society must be able to Develop proficiency and fluency with the tools of technology; Build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought; Design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes; Manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information; Create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts; Attend to the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments (NCTE, 2013). Figure 2. Urban Food Collective course action, by semester. UFC I A. Read and discussed course readings B. Maintained reflective journal C. Cultivated rooftop garden D. Distributed food via Food Not Bombs community partner E. Supported local school’s community engagement (garden installation and supplies, food production education, outreach) F. Produced local food news ‘zine’ with interviews G. Hosted Movie Night H. Co-constructed four single-family gardens in low-income neighborhood I. Co-constructed school and homeless shelter gardens UFC II A. Read and discussed course readings B. Cultivated rooftop garden C. Distributed food to various recipients in and out of class D. Composed Community Food Assessment E. Hosted Community Supper to encourage local food system participation UFC III A. Read and discussed course readings B. Participated in online class discussion forum C. Cultivated rooftop garden D. Distributed food to homeless shelter and among students E. Developed and publicized mayoral petition detailing expansion of local food system F. Conducted ‘Fun with Food’ weekly afterschool program (created cookbook, participatory food demonstrations, and gardens at four community centers) G. Composed academic paper and presentation on aspect of local food system 19 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 20 UFC IV A. Read and discussed course readings B. Maintained reflective journal C. Cultivated rooftop garden D. Distributed food in various ways E. Publicly protested public space food restrictions via garden display, potluck, and public forum F. Founded Campus Kitchens, a food reclamation program G. Distributed plants propagated by UFC members and others to school and community gardens H. Co-constructed school garden I. Composed articles to raise awareness of local food system issues J. Coordinated activist networking summit UFC V A. Read and discussed course readings B. Collaboratively maintained topical journals C. Cultivated rooftop garden D. Distributed food in various ways E. Canvassed neighborhoods to build support for community garden Figure 3. Two dimensions of economic impact. Direct Isolated Networked Mediated Figure 4. Course Activities from Fig 3—Insulated or Connected (x-axis) and Mediated or Direct (y-axis). UFC I Projects 20 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 21 Direct Isolated Is ol at ed Networked Mediated UFC II Projects Direct Isolated Networked Mediated UFC III Projects Direct Isolated Networked Mediated UFC IV Projects Direct Isolated Networked Mediated 21 LITERACY IN ECONOMIC DOMAIN 22 UFC V Projects Direct Isolated Networked Mediated Figure 5. Combined Graph: Connectedness and Directness of Course Action, UFC I-V 2 Direct 1 Isolated -2 Networked 0 -1 0 1 2 -1 -2 Mediated Figure 6. Comparand: Course Action from Syllabi in Three Related Courses in Human Geography taught by the same instructor. 2 Direct 1 Isolated -4 Networked 0 -2 0 2 4 -1 -2 Mediated 22