Aggregate Expenditure

advertisement

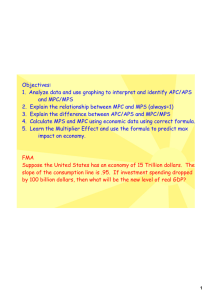

Aggregate Expenditure Outline •Components of aggregate expenditure •Planned and unplanned expenditure •The consumption function •Imports and GDP •Equilibrium expenditure •The expenditure multiplier Components of Aggregate Expenditure Recall from Chapter 5 that aggregate expenditure for final goods and services equals the sum of •Consumption expenditure, C •Investment, I •Government purchases of goods and services, G •Net exports, NX Thus: Aggregate expenditure = C + I + G + NX Planned and Unplanned Expenditures Aggregate expenditure aggregate income and real GDP. But aggregate planned expenditure might not equal real GDP because firms can end up with larger or smaller inventories than they had intended. Aesop’s Bottles B.C. 400 Investment Plans Planned spending on buildings, equipment, and tools 20,000 drachmas Planned inventory investment 0 drachmas Value of inventories on Dec. 31, 401 B. C. 11,000 drachmas Value of inventories on Dec. 31, 400 B.C. 13,500 drachmas Unplanned inventory investment in 400 B.C. 2,500 drachmas Actual investment in 400 B.C. 22,500 drachmas Autonomous versus induced Expenditure •Autonomous expenditure: The components of aggregate expenditure that do not change when real GDP changes. •Induced expenditure: The components of aggregate expenditure that change when real GDP changes. The Consumption Function The consumption function shows the relationship between consumption expenditure and disposable income, holding all other influences on influences on household spending behavior constant. What is disposable income? •Disposable income is aggregate income (GDP) minus net taxes •Net taxes are taxes paid to government minus transfer payments received from government. Disp osable Income and Consumptio n in th e U.S., 1959-99 7000 www.bea.gov 6000 1991 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Disp osable Income (billions o f 1996 dollar s) 7000 450 line Consumption (trillions of 1996 dollars) Saving F Consumption function E D 6.0 Dissaving C Saving is zero B 2.0 A 2.0 6.0 10.0 Disposable income (trillions of 1996 dollars) (trillions of 1996 dollars) Disposable income Planned Consumption Expenditure 0 2.0 4.0 6.0 8.0 10.0 1.5 3.0 4.5 6.0 7.5 9.0 A B C D E F Notice that autonomous consumption is given by point A. This is planned consumption expenditure when disposable income is zero ($1.5 trillion). This spending must be financed by past saving or by borrowing Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction of the change in disposable income that is spent on consumption. That is: MPC = Change in consumption expenditure Change in disposable income Notice that when disposable income increases from $6 to $8 trillion, consumption expenditure changes from $6.0 to $7.5 trillion. Thus we have: $1.5trillion MPC 0.75 $2.0trillion Consumption (trillions of 1996 dollars) MPC gives the slope of the consumption function Consumption function E 7.5 6.0 D rise K run rise EK $1.5trillion Slope MPC 0.75 run KD $2.0trillion 0 6.0 8.0 Disposable income (trillions of 1996 dollars) Disposable income + (Expected) real interest rate The buying power of net assets Expected future disposable income + + Real Consumption Spending Consumption (trillions of 1996 dollars) Shifts of the consumption function CF 1 CF0 CF2 CF0 to CF1 •Decrease in the real interest rate. •Buying power of net assets increases. •Rise in expected future disposable income. 0 Disposable income (trillions of 1996 dollars) Falling interest rates have stimulated consumer spending recently Complete Exercise #1 on p. 394 Imports and GDP Imports are a component of induced expenditure. Imports depend partly on the health of the domestic economy. Marginal Propensity to import (MPI) The marginal propensity to import (MPI) is the fraction of the change in disposable income that is spent on imports . That is: MPI = Change imports Change in disposable income Suppose that, ceteris paribus, when disposable income increases from $2 trillion, imports increase by $0.3 trillion. Thus we have: $0.3trillion MPI 0.15 $2.0trillion Aggregate Expenditure and Real GDP Planned Expenditures [Y] [C] [I] [G] [X] [M] [AE = C + I + G +X - M] (trillions of 1996 dollars) A 0.00 0.00 2.00 1.00 1.50 0.00 4.50 B 3.00 2.25 2.00 1.00 1.50 0.75 6.00 C 6.00 4.50 2.00 1.00 1.50 1.50 7.50 D 9.00 6.75 2.00 1.00 1.50 2.25 9.00 E 12.00 9.00 2.00 1.00 1.50 3.00 10.50 F 15.00 11.25 2.00 1.00 1.50 3.75 12.00 Note: Y is real GDP I+G+C+X Agg. Exp. (billions of 1996 dollars) imports AE D Consumption expenditure C 4.5 I+G+X A 3 0 I+G I 9 GDP (Billions of 1996 dollars) Real GDP Aggregate Unplanned planned inventory expenditure change (trillions of 1996 dollars) A 0.0 0.0 -4.5 B 3.0 3.0 -3.0 C 6.0 6.0 -1.5 D 9.0 9.0 0.0 E 12.0 12.0 1.5 F 15.0 15.0 3.0 AE (trillions of 1996 dollars) 12 AE J F D 9 B 6 K 450 0 3 9 15 GDP (trillions of 1996 dollars) •AE > GDP by vertical distance B-K •Plans of producing and spending units do not coincide •Unplanned inventory investment = - $3 trillion •Tendency for firms (on average) to step up the pace of production and offer more employment • GDP > AE by vertical distance J-F •Plans of producing and spending units do not coincide •Unplanned inventory investment =$3 trillion •Tendency for firms (on average) to scale back the on production and offer less employment •AE = GDP •Plans of producing and spending units coincide. •Unplanned inventory investment = 0 • No tendency for firms (on average) to step up the pace of production and offer more employment. Nor is there a tendency for firms to scale back on production and offer less employment. Say’s Law1 •“Supply creates its own demand.” •By producing goods and services, firms create a total demand for goods and services equal to what they have produced. Say’s law apparently rules out the possibility of a widespread glut of goods. 1 J.B. Say. Treatise on Political Economy, 1903. Say’s law implies that full-employment equilibrium is the normal state of affairs AE C + I + G + NX AE touches the 450 line at potential GDP Full employment GDP GDP General (Keynesian) Case: Underemployment Equilibrium AE A C + I + G + NX H Y* Full employment GDP GDP •Assume the economy is in equilibrium when real GDP = $3 trillon. •What would happen if, other things being equal, planned investment (I) increased by $0.5 trillion? How did a $0.5 trillion change in I bring about a $2 trillion change in GDP? AE AE2 2 AE1 1 5 I 4.5 GDP 450 0 9.0 11.0 GDP It’s a bird It’s a plane No, it’s the multiplier effect! The expenditure multiplier The multiplier is amount by which a change in any component of autonomous expenditure is magnified or multiplied to determine the change that it generates in equilibrium expenditure and real GDP. Change in equilibrium expenditure Multiplier = Change in autonomous expenditure Thus in our case the multiplier is given by: Y $2trillion Multiplier 4 I $0.5trillion Chain of causation When firms increase investment by $0.5 trillion, sales revenues at investment goods manufacturers (Boeing, Westinghouse, Cincinnati Milacron) will increase by $0.5 trillion The $0.5 trillion in revenue will be distributed as factor payments to those supplying resources necessary to produce capital goods—hence the change in spending generates $0.5 trillion in income in the first round. Now households have $1,000 in additional income. What do they do with it? Their spending will increase by the MPC times the change in income—that is: C = .75 $0.5 trillion = $0.375 trillion Hence, households spend $375 billion and save $125billion But the story does not end here, since McDonalds’s, Disney, Kraft, American Airlines, and Amheiser Busch, etc. will see their sales increase by $375 billion, and will distribute $375 billion in wages, salaries, rental income, and profits to those who supplied resources necessary to produce the additional consumer goods. Those who earned additional income in consumer goods industries will now increase their spending. By how much? C = .75 $375 = $281.85. This will result in additional production and factor payments. Spending will then increase. And so on. And so on. Why is the multiplier greater than 1? As we see from the preceding illustration, a change in autonomous expenditure (in this case, I) induces a change in consumption expenditure. The Multiplier and the MPC We will now illustrate why the magnitude of the multiplier depends on the MPC. For the moment, assume no imports, exports, or taxes. Thus: Y C Y [1] Where: C MPC Y [2] Now substitute [2] into [1] to obtain: Y MPC C I [1] Now solve for Y (1 MPC ) Y I [4] Now rearrange [4] 1 Y I (1 MPC ) [5] Divide both sides of [5] by I to obtain the multiplier Multiplier Y 1 1 1 4 I (1 MPC ) (1 0.75) 0.25 The expenditure multiplier You can see from the math that the size of the multiplier is positively linked to the MPC. The higher the MPC, the greater the “induced” expenditure resulting from a change in autonomous expenditure Taxes, Imports, and the Multiplier Once we allow for imports and taxes, the multiplier depends not only on the MPC, but also on the marginal propensity to import (MPI) and the marginal tax rate (MTR) Marginal Tax Rate (MTR) The marginal tax rate (MTR) is the fraction of the change in real GDP that is paid income taxes. That is: MTR = Change in tax payments Change in real GDP Suppose that, ceteris paribus, when real GDP increases by $0.5 trillion, tax payments increase by $0.05 trillion. Thus we have: $0.05trillion MTR 0.1 $0.5trillion The “real” expenditure multiplier The multiplier is given by Multiplier Y 1 I (1 Slope of AE curve) The slope of the AE curve is given by: Slope of AE curve = MPC – (MPI + MTR) Thus the multiplier can be written as: Multiplier Y 1 I 1 MPC MPI MTR In this case, MPC = 0.75; MPI = 0.15; MTR = 0.1 AE Slope = 0.5 AE2 2 AE1 1 5 Multiplier I Y $1.0 trillion 2 I $0.5 trillion 4.5 Y 450 0 9.0 10.0 GDP