Document

advertisement

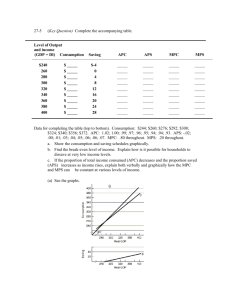

“ I believe myself to be writing a book on economic theory which will largely revolutionize—not, I suppose, at once but in the course of the next ten years— the way the world thinks about economic problems. ” -- John Maynard Keynes The book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money , systematically analyzed the relationship between changes in aggregate expenditure and changes in GDP. In any particular year, the level of GDP is determined mainly by the level of aggregate expenditure. Real GDP 370 390 C 375 390 410 430 450 470 S Ig C + Ig ______ ______ 20 ______ ______ ______ Unplanned Inventory ______ ______ 405 420 435 450 ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ 490 510 530 465 480 495 ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ 550 510 ______ ______ ______ ______ GDP - C Real GDP 370 390 C 375 390 410 430 450 470 S Ig C + Ig -5 0 20 20 395 410 Unplanned Inventory 25 20 405 420 435 450 5 10 15 20 20 20 20 20 425 440 455 470 15 10 5 0 490 510 530 465 480 495 25 30 35 20 20 20 485 500 515 -5 -10 -15 550 510 40 20 530 -20 GDP - C C 0 GDP Real Consumption A smooth, upward trend, interrupted infrequently by brief recessions. After taxes (-) and transfers (+) Every $1 increase increases consumption by 4-5 cents Doesn’t seem to have much affect up or down Price levels affect real wealth more than total consumption Higher rates - more savings, lower rates - more consumption GDP C S 1500 1540 ____ 1600 1620 ____ 1700 1700 ____ 1800 1780 ____ 1900 1860 ____ 2000 1940 ____ 2100 2020 ____ 2200 2100 ____ Planned consumption (trillions of $) 45º line 12 Saving C 9 Dis-saving 6 3 45º 3 6 9 12 Real disposable income (trillions of dollars) Savings Consumption The Relationship between Consumption and Income, 1960–2010 The line, which represents the relationship between consumption and disposable income, is called the consumption function. The slope of the consumption function is the marginal propensity to consume. Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) The slope of the consumption function: The amount by which consumption spending changes when disposable income changes. MPC Change in consumptio Change in disposable n income C YD Between 2006 and 2007, disposable income increased by $228 billion and consumption spending increased by $208 billion. C YD $208 billion $228 billion 0 . 91 Marginal propensity to save (MPS) The amount by which saving changes when disposable income changes. Between 2006 and 2007, disposable income increased by $228 billion and if consumption spending increased by $208 billion, then savings increased by $20 billion. S YD $20 billion $228 billion 1 = MPC + MPS 0 . 09 Calculating the MPC and MPS Real GDP Consumption $9,000 $8,000 10,000 8,600 11,000 9,200 12,000 9,800 13,000 10,400 Calculating the MPC and MPS Real GDP Consumption Saving $9,000 $8,000 1000 10,000 8,600 1400 11,000 9,200 1800 12,000 9,800 2200 13,000 10,400 2600 Calculating the MPC and MPS Real GDP Consumption Saving MPC MPS $9,000 $8,000 1000 .60 .40 10,000 8,600 1400 .60 .40 11,000 9,200 1800 .60 .40 12,000 9,800 2200 .60 .40 13,000 10,400 2600 .60 .40 MPC MPS C Y S Y $ 8 , 600 $ 8 , 000 $ 10 , 000 $ 9 , 000 $ 1, 400 $ 1, 000 $ 10 , 000 $ 9 , 000 $ 600 0 .6 $ 1, 000 $ 400 $ 1, 000 0 .4 Real Investment Planned Investment Higher rates - more savings, lower rates - more consumption Corporate taxes (-) Investment tax credits (+) The more profitable a firm is, the greater its cash flow and the greater its ability to finance investment. Unplanned Inventory Reduction Planned consumption (trillions of $) 45º line 12 Saving C 9 Dis-saving 6 Unplanned Increases in Inventory 3 45º 3 6 9 12 Real disposable income (trillions of dollars) Lower inflation rates attract more consumption Higher incomes increase consumption Appreciating currency increases import consumption, but decreases export consumption. Planned aggregate expenditures Equilibrium (trillions of $) Keynesian equilibrium 10.3 10.0 9.7 (AE = GDP) AE = C + I + G + NX AE = C + I + G AE = C + I AE = C Full Employment (potential GDP) 45º Output 9.4 10.0 10.6 (Real GDP -trillions of $) Planned aggregate expenditures (trillions of $) (AE = GDP) AE = C + I + G + NX,P1 AE = C + I + G + NX,P2 AE = C + I + G + NX, P3 10.6 10.0 9.4 Output (Real GDP -trillions of $) 45º 9.4 10.0 10.6 P3 P2 P1 AD 9.4 10.0 10.6 • The Multiplier: A change in an spending (e.g. investment) leads to an even larger change in output and employment. • The multiplier is the number by which the initial change in spending is multiplied to obtain the total increase. • The size of the multiplier depends on how much is spent of each increase. • The greater this %, the greater the effect •injections will increase the size of the multiplier; •leakages will decrease the size of the multiplier, Expenditure stage Additional income Additional consumption Marginal propensity to consume (dollars) (dollars) Round 1 Round 2 Round 3 Round 4 Round 5 All others 1,000,000 750,000 562,500 421,875 316,406 949,219 750,000 562,500 3/4 3/4 421,875 316,406 237,305 711,914 3/4 3/4 3/4 3/4 Total 4,000,000 3,000,000 3/4 For simplicity (here) it is assumed that all additions to income are either spent domestically or saved. • The multiplier concept is based upon the proportion of additional income that households choose to spend (here assumed to be 75% = 3/4). Assume the people will spend .8 (80%) of a change in their income and the change in business investment is $10 (billion). Complete the table below. How much will they save? ______ change in income change in consumption change in savings + $10 ______ ______ 2nd round ______ ______ ______ 3rd round ______ ______ ______ 4th round ______ ______ ______ 5th round ______ ______ ______ 16.38 13.10 3.28 ______ ______ ______ increase in investment of $10 billion all other rounds Totals Higher Spending Means a Larger Multiplier MPC Size of multiplier 9/10 4/5 3/4 2/3 1/2 1/3 10.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 1.5 • As the spending % increases more and more money of every injection is spent (and so received as payment and then spent again, received as payment and spent again, etc.). • The effect is that for higher spending, higher multipliers result, specifically the relationship follows this equation: 1 M = 1 - %spent Calculating the effect of the multiplier: change in the injection % not spent (saved) Change in investment % saved multiplier effect $10 20% ________ $10 10% ________ $10 25% ________ $20 20% ________ Total Output (Real GDP) Planned Aggregate Expenditures $5,000 $5,250 5,500 5,500 6,000 5,750 6,500 6,000 7,000 6,250 a. If the current output rate is $5,000, what will tend to happen to business inventories, future output, and employment? b. If the current output rate is $6,500, what will tend to happen to business inventories, future output and employment? c. What is the equilibrium rate of income of this economy? d. If the economy’s full employment rate of output is $6,000, will the rate of unemployment be high, low, or normal, assuming the current planned demand persisted into the future? e. What would happen if there was an increase in investment of $250? Keynesian View of the Business Cycle During a downturn, business pessimism, declining investment, and the multiplier principle combine to plunge the economy further toward recession. During an economic upswing, business and consumer optimism and expanding investment interact with the multiplier to propel the economy to an inflationary boom. • The theory suggests that a market-directed economy, left to its own devices, will tend to fluctuate between economic recession and inflationary boom. Keynesian View of the Business Cycle • Regulation of aggregate expenditures is the crux of sound macroeconomic policy according to the Keynesian view. • If we could assure aggregate expenditures large enough to achieve capacity output, but not so large as to result in inflation, the Keynesian view implies that maximum output, full employment, and price stability would be attained.