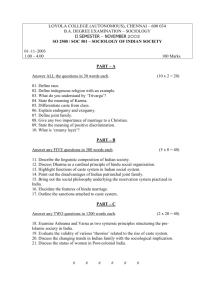

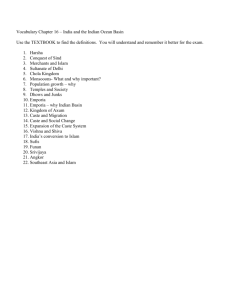

Indian Society 12th NCERT Sociology

advertisement