The effect of music listening on spatial skills: The role of processing

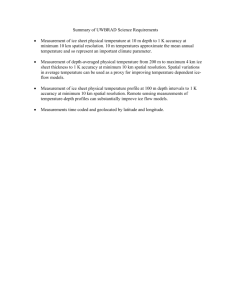

advertisement

The effect of music listening on spatial skills: The role of processing time Doris Grillitsch, Department of Psychology Richard Parncutt, Department of Musicology University of Graz, Austria International Conference of Music Perception and Cognition Sapporo, Japan, August 2008 “Mozart effect” Rauscher, Shaw & Ky (1993) listening to music can improve spatial ability small effect, short period 3 conditions: Mozart Sonata in D major for 2 pianos relaxation CD (voice only) no music (sit in silence) Humans versus rats Rauscher, Robinson & Jens (1998) repeated pre- and postnatal music exposure can improve rats’ ability to negotiate a maze depends on kind of music But: Can rats hear anything before birth? Any pre- and postnatal sensory exposure can affect brain development What aspect of “musical” structure did it? Die Musik an sich? Thompson, Schellenberg & Husain (2001) “Mozart effect” is an artifact of arousal mood It’s not about Mozart - not even about music! The role of preference Hypothesis: listener must like sound stimulus or identify with it Nantais & Schellenberg (1999, Expt 2) better spatial skills after hearing preferred stimulus choice between Mozart Sonata and short story Time on spatial task Time not reported: Rauscher et al. (1993) Schellenberg & Hallam (2005) Ivanov & Geake (2003) – spatial skills are better evaluated without time limit (Silverman, 1999) Time limit (1 minute per task): Thompson et al (2001) Nantais & Schellenberg (1999) What about motivation? Definition tendency to engage with spatial task Measure time spent on task Relevance expertise approach to musical ability Question Does flow matter? Adjust difficulty to ability? Playfulness Schellenberg, Nakata, Hunter & Tamoto (2007): Children heard familiar songs or unfamiliar music Familiar group spent more time drawing pictures Their pictures were rated more creative Did familiar songs make the children more playful? persistent? Does time spent have more important implications for musical development than the “Mozart effect”? Our experiment Music conditions fast happy music start of Mozart Sonata in D for 2 pianos, KV 448 personal favorite music mostly pop slow sad music start of Mozart Fantasy in D minor (KV 397) silence (control) Measures enjoyment of music spatial skill measure mood time spent on spatial tasks Participants 4 groups @ 10, random assignment undergraduate students in various disciplines (mainly psychology) average age: 24 years Procedure 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Instructions for spatial skills task* Music (or silence) for 3 minutes Mood questionnaire Spatial skills tasks Mood questionnaire How much did you enjoy the music? * Due to short duration of “Mozart effect” Mental rotation task A3DW (Gittler, 1999), standard version S2 test cube none of them don`t know Mental rotation task Adaptive procedure (A3DW) The difficulty of each task is matched to the estimated spatial skill of the participant. The skill measure (“parameter”) is updated after each task. The system stops after 10 items if the measure is stable. maximum 17 items Results spatial skill “parameter” = final estimate of spatial ability no significant difference among the groups no direct effect of music on spatial skills no „Mozart effect“ Results working time per task large & highly significant effect of music on time spent per rotation task (F3, 32 = 6.123; p = 0.002) significant difference (Tukey) between – favourite music – Mozart Sonata and control A second analysis Rauscher et al. (1993): spatial skills effect limited to 10-15 minutes We repeated our analysis for data obtained in first 15 minutes after music stopped 23 of our 40 participants spent less than 15 minutes on mental rotation tasks repeat analysis was different for only 17 participants For these we now considered: (i) (ii) average time spent on each task before 15 minutes spatial skills measure at 15 minutes Results spatial skill at 15 min again: no significant effect of music on task performance Results working time per task first 15 min again: large & highly sig. effect of music on time spent per rotation task (F3, 32 = 6.350; p = 0.002) again: significant difference (Tukey) between – favourite music – Mozart Sonata and control Mood monitored before and after rotation tasks standardised test: EWL 60 S (Janke & Debus, 1978) rate own mood from a list of adjectives Only one sig. effect of music on mood: deterioration for favourite music group (z = -2.555; p = 0.011) Possible explanations: Improved mood after preferred music Longer time spent on rotation tasks Enjoyment of music Just checking: We asked the three experimental (music) groups how much they had enjoyed the music. significant effect of group (F2, 24 = 3.714; p = 0.039) favourite music group enjoyed music more than Mozart Sonata group (Tukey) Favorite music more time on subsequent task. Why? 1. Favourite music improves mood • more relaxed, less afraid of mistakes • less afraid of seeming unintelligent • holiday behavior: avoid stress, take your time 2. Positive emotion of the music is incompatible with subsequent task • motivation falls, speed of working falls 3. Favourite music induces playfulness • try out many different task solutions • more persistent, give up less easily Play and skill acquisition Skills are often developed in a playful manner e.g. language, creativity, use of tools and symbols, problem solving, anxiety management, conflict resolution (Bruner, Jolly, & Sylva, 1976) Specific skill levels depend primarily on total amount practice time (Ericsson et al., 1993) playfulness repetitions skill? Is music a virtual person? Music (and especially preferred music) expresses personal states such as anger expresses personal attributes such as femininity linked to spirituality alleviates pain and loneliness Children play with more engagement and for longer periods when their mother is available but passive (Slade, 1987). Do children play independently for longer when familiar music is playing in the background? In this study: Did familiar music make participants feel more emotionally secure and able to focus attention on the task? Caveats Our spatial skills test was too complex Results may depend on age – as does “open-earedness” Future work simpler spatial skill task additional measures – behavioral and physiological measures of arousal – behavioral measure of mood Summary Listening to favorite music increases time spent on subsequent spatial task Music may promote learning by promoting playfulness literature Bruner, J. S., Jolly, A., & Sylva K. (Eds., 1976). Play—Its role in development and evolution. New York: Basic. Ericsson, K. A. Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100. 363-406. Gittler, G. (1999). Adaptiver 3-dimensionaler Würfeltest A3DW (Version 23.00) [Computer Software]. Mödling, Austria: Schuhfried. Gittler, G. (1990). Dreidimensionaler Würfeltest (3DW). Ein Rasch- skalierter Test zur Messung des räumlichen Vorstellungsvermögens (Theoretische Grundlagen und Manual). Weinheim: Beltz Test GmbH. Ivanov, V. K. & Geake, J. G. (2003). The Mozart Effect and primary school children. Psychology of Music, 31(4), 405-413. Janke, W. & Debus, G. (1978). Die Eigenschaftswörterliste Selbstbeurteilungs-Skala (S) (EWL 60 S). Göttingen: Hogrefe. Nantais, K. M., & Schellenberg, E. G. (1999). The Mozart effect: An artifact of preference. Psychological Science, 10 (4), 370-373. Parncutt, R., & Kessler, A. (2006). Musik als virtuelle Person. In R. Flotzinger (Ed.), Musik als... Ausgewählte Betrachtungsweisen (pp. 9-52). Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. literature Rauscher, F. H., Robinson, K. D., & Jens, J. J. (1998). Improved maze learning through early music exposure in rats. Neurological Research, 20, 427-432. Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., & Ky, K. N. (1993). Music and spatial task performance. Nature, 365, 611. Schellenberg, E. G. (2005). Music and cognitive abilities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 (6), 317-320. Schellenberg, E. G. & Hallam, S. (2005). Music listening and ccgnitive abilities in 10- and 11-year-olds: The Blur effect. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1060. Schellenberg, E. G., Nakata, T., Hunter, P. G., & Tamoto, S. (2007). Exposure to music and cognitive performance: Tests of children and adults. Psychology of Music, 35, 5-19. Slade, A. (1987). A longitudinal study of maternal involvement and symbolic play during the toddler period. Child Development, 58, 367-375. Thompson, W. F.; Schellenberg, E. G., & Husain G. (2001). Arousal, mood and the Mozart effect. Psychological Science, 12 (3), 248-251. Many thanks for your attention Ideas from the discussion Which was more important for spatial skills, arousal or liking? Did the students like the Fantasie more than the Sonata? Did ability increase during the spatial skills task? Is it possible to approach this kind of spatial task playfully? Or Rauscher’s paper folding task? What kind of music did the students in the favorite music group bring? Arousal? Valence? Do these results imply that the people in the favorite music group were less good at the spatial task? They took twice as long but were not better.