Using Local Labor Market Data to Guide High

advertisement

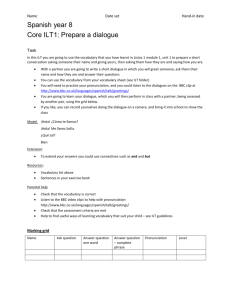

Webinar: Meeting Students’ Needs through Increased Learning Time September 18, 2014 WebEx Instructions 2 WebEx instructions Attendees can provide nonverbal feedback to presenters utilizing the Feedback tool. 3 WebEx instructions Feedback options: 4 WebEx instructions Responses to poll questions can be entered in the Polling Panel. Remember to click “Submit” once you have selected your answer(s). 5 WebEx instructions Attendees should utilize the “Q&A” feature to pose questions to the speaker, panelists, and/or host. The host will hold all questions directed toward the speaker or panelists, and they will be answered during a Q&A session at the end of each discussion. 6 Welcome and Overview Dr. Lydotta Taylor Task 2 Lead REL Appalachia What is a REL? • A REL is a Regional Educational Laboratory. • There are 10 RELs across the country. • The REL program is administered by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES). • A REL serves the education needs of a designated region. • The REL works in partnership with the region’s school districts, state departments of education, and others to use data and research to improve academic outcomes for students. 8 What is a REL? 9 REL Appalachia’s mission • Meet the applied research and technical assistance needs of Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. • Conduct empirical research and analysis. • Bring evidence-based information to policy makers and practitioners: – Inform policy and practice—for states, districts, schools, and other stakeholders. – Focus on high-priority, discrete issues and build a body of knowledge over time. http://www.RELAppalachia.org Follow us! @REL_Appalachia 10 What Does the Research Say about Increased Learning Time and Student Outcomes? Introducing the new REL Appalachia report Dr. Jim Lindsay Senior Research Analyst American Institutes for Research Why this study? • Districts are considering increased learning time (ILT) programs as school improvement strategies. • A summary of research on impacts of ILT programs can inform districts’ choices on type of programs to adopt. 12 Unique features of REL Appalachia review • Previous reviews: single approaches to ILT. – Out-of-school programs. – Summer school programs. – Expanded learning time schools. – Year-round schools. • Research base is expanding, studies getting better. • Review standards that focus on most rigorous studies. • Examination of effects for approaches, outcomes types, student subgroups. 13 Research questions • To what extent do the four types of ILT approaches affect student outcomes: – Out-of-school programs? – Summer school? – Expanded learning time schools? – Year-round schools? • What are the effects of ILT program characteristics, such as instructors’ qualifications, instruction approach, and teacher-to-student ratio? • Are ILT programs effective for: – Students at risk of academic failure? – Students in urban, suburban, and rural schools? – Students in elementary and secondary grades? 14 Review methodology • Broad search for studies on ILT: – Articles, reports, dissertations from 12 databases of research literature. – Other reviews. – Internet search. – Websites of funding organizations and associations. – Inquiries to researchers and funders. • Systematic screening process for relevance. • Review criteria for rigor: What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) group design standards. • Combining findings from studies: meta-analysis with conservative assumptions. 15 Sample of studies • Initial pool of studies: 7,000+ • After screening out nonrelevant studies (6,835) and studies not meeting WWC standards (165), 30 studies remained. K-5 16 2 11 1 Mixed 11 Low 19 0-5 11-20 21 or more 6 South 11 Northeast 2 Midwest 2 National Study 5 Cannot tell 6 4 Urban 4 Locale 6-10 4 West 6-8 9-12 Cannot tell Region K-8 Number of Studies 0 5 10 15 20 5 6 Cannot tell 9 0-50 51-100 13 1-1,000 5 1,000 or more 5 13 Suburban 4 Rural and Urban 2 Rural 2 National Study 7 Student Needs SocioNumber of Econo Students in the Number of Schools mic Study in the Study Status Grade Range Number of Studies 0 5 10 15 20 5 Below_Standards Behavior_Problems ADHD 4 2 4 16 Sample of studies (continued) Characteristics of ILT Programs Characteristics of Study Reports Number of Studies 5 10 15 K-5 Region 11 1 Mixed 11 Low South 11 Northeast 2 Midwest 2 5 4 Urban Locale 4 5 21 or more 6 Cannot tell 9 0-50 51-100 13 1-1,000 5 1,000 or more 5 13 Suburban 4 Rural and Urban 2 Rural 2 National Study 7 5 Below_Standards Behavior_Problems ADHD 20 6 Cannot tell 6 15 4 National Study 19 0-5 11-20 10 West 2 6-8 6-10 5 Cannot tell 16 K-8 9-12 0 20 Student Needs Number of Students in the Study SocioNumber of Schools in Economi the Study c Status Grade Range 0 Number of Studies 4 2 4 17 Findings • Across all studies, out-of-school programs had a positive effect on students’ academic motivation, but not on literacy or math achievement. – Effect was not substantial. – Not all programs/program features produce positive impacts on all outcomes. 18 Findings (continued) • Characteristics of programs or samples that showed positive effects: – Certified teachers and traditional instruction each had a positive effect on students’ academic outcomes; experiential instruction had a positive effect on social-emotional skill development. Effects were statistically significant but not substantial. – ILT had a small effect on the literacy achievement of students not at risk for academic failure, but a substantial effect for students below standards. – ILT had a positive effect on the math achievement of students not at risk. – ILT had a substantial positive effect on the social-emotional skill development of students with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. 19 Findings (continued) • Characteristics of programs or samples that showed positive effects (continued) – ILT had substantial positive effects for students in suburban settings (literacy achievement). – ILT had a positive effect for students in mixed settings (math achievement and academic motivation). – ILT had a positive effect for academic outcomes for students in elementary grades, but ILT might have a negative effect for students in middle school grades. 20 In summary • The review was broad, systematic, impartial, and included only studies capable of finding causal impacts. • No single type of ILT works for all students, in all settings, and for all outcomes. – Each district should consider the desired goal of its ILT program, the characteristics of the ILT, and the types of students who could best benefit from the ILT. 21 In summary Program Features, Student Groups, and Circumstances Under Which ILT Produces Statistically Significant Outcomes ILT produced negative results when... Implementation features Outcome Literacy Achievement Math Achievement ILT produced positive results when... Students are in middle school grades (4 studies) Teachers are certified (10 studies) Instruction is traditional (9 studies) Teachers are certified (5 studies) Student groups Settings Students are below standards (3 studies) Participants live in suburban locales (3 studies) Students are not at risk (4 studies) Students are not at risk (3 studies) Students are in elementary grades (13 studies) Participants live in a variety of locales (4 studies) Instruction is traditional (4 studies) Students are in elementary grades (6 studies) Academic Motivation Out-of-school program approach is used (10 studies) Participants live in a variety of locales (4 studies) Social-Emotional Skill Development Instruction is experiential (4 studies) Students have ADHD (3 studies) Bold bullet points are findings that are large enough to be considered substantially important (g > .25 standard deviations). 22 Q & A discussion 23 Translating the Evidence on Increased Learning Time into Practice Dr. Yael Kidron Senior Research Analyst American Institutes for Research Actionable, research-based practice guide • Provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (IES). • Written by an expert panel. • Based on research vetted by the WWC. 25 1. Align the program academically with the school day • Maintain ongoing communication between teachers and the out-ofschool program staff. • Designate a school-based coordinator. • Provide information to the out-of-school provider about schoolbased goals and learning objectives. • Hire school staff for out-of-school programs. • Follow FERPA guidelines for protecting student information. 26 2. Maximize student participation and attendance • Design program features to meet the needs and preferences of students and parents. • Promote awareness of the program within the school and to parents. • Use attendance data to identify students facing difficulties in attending the program. 27 3. Adapt instruction to student needs • Use formal and informal assessment data to inform academic instruction. • Use one-on-one tutoring if possible; otherwise, break students into small groups. • Provide professional development and ongoing support to all instructors. 28 4. Provide engaging learning experiences • Make learning relevant by providing practical examples and linking instruction to students’ interests and experiences. • Make learning active through collaborative learning and hands-on projects. • Build adult-student relationships. 29 5. Assess program performance • Develop an evaluation plan. • Collect program and student performance data. • Analyze data and use findings for program improvement. 30 School Turnaround Learning Community (STLC) • http://schoolturnaroundsupport.org/ 31 Searching the STLC resource library 32 Q & A Discussion 33 Aligning Increased Learning Time Academic Supports with Student Data Dr. Joe McKown Vice President The National Center on Time & Learning Closing the achievement and opportunity gaps Generate Knowledge: Document and disseminate effective practices of highperforming expanded learning time charter and district schools across the country. Improve School Practice: Through technical assistance, grow and strengthen the number of highquality expanded learning time schools nationally. Build Support: Build broad-based support to bring highquality expanded learning time school opportunities to all high-poverty students over time. Inform Policy: Support policy development and leverage federal, state, and local funding to support high-quality expanded learning time implementation. 35 NCTL’s principles of expanded learning time (ELT) • Significantly more learning time for all students. • A balanced approach to the school day—more time for core academics, enrichment, and teacher collaboration. • A catalyst for school redesign and turnaround. • Better integration of community partnerships and expertise into the school day. • Deeper implementation of school and district priorities. 36 Relationship between time and achievement Analysis of three years of test data from Illinois schools found a direct correlation between more time in reading and math and higher student achievement. Dennis Coates. (2003, December). Education production functions using instructional time as an input. Education Economics, 11(3), 273-292. Twenty-five (25) percent more instructional time and high dosage tutoring were two of the strongest predictors of higher achievement. Will Dobbie & Roland G. Fryer, Jr. (2011, December). Getting beneath the veil of effective schools: Evidence from New York City (NBER Working Paper, No. 17632). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Students who attended charter schools with significantly more time performed much better than peers in charter schools with more conventional calendars. Caroline Hoxby & Sonali Muraka,. (2008, Summer). New York City charter schools: How well are they teaching their students? Education Next, pp. 54-61. 37 More time benefits both students and teachers More Time to Raise Student Achievement More Time to Provide Rich Engagement Offerings for Students More Time to Collaborate and Improve Quality of Instruction 38 © 2014 National Center on Time and Learning; www.timeandlearning.org Seven essential elements of high-quality ELT schools See NCTL’s Time Well Spent for a detailed discussion of the practices of 30 ELT schools serving high-poverty populations with impressive track records of student success: http://www.timeandlearning.org/?q=time-well-spent-0. 39 High-quality intervention: Coordinated execution 40 Pennington Elementary School (Wheat Ridge, CO) A high-quality targeted intervention encompassing all of the elements needed to differentiate based on student need. 41 Pennington Elementary School (continued) Differentiation supported by dedicated meeting time to analyze data for student grouping adjustments Sample Grade 2 Student Schedule Start Time: 7:45 a.m. Breakfast + Assembly Literacy Intervention All students receive intervention in groups of 2-8 students based on intensity of support needed and areas of weakness. Literacy Core Lunch + Recess Specials Read Aloud Math Core Math Intervention Science/Social Studies End Time: 4:15 p.m. Enrichment Elective One period/week: Vertical intervention teams (by support level provided) meet to: 1. Discuss progress monitoring data. 2. Regroup students. 3. Identify intervention strategies to move students forward. 42 Additional examples/resources For more information about how expanded learning time schools are implementing high-quality targeted intervention and acceleration based on data analysis: Time Well Spent www.timeandlearning.org/timew ellspent.pdf 43 Q & A Discussion 44 Expanded Learning Opportunities: A Smart Investment Virginia Partnership for Out-of-School Time (VPOST) Blaire Denson Director Virginia Partnership for Out-of-School Time Virginia Partnership for Out-of-School Time (VPOST) • Statewide public-private initiative. • Mission: Develop and expand academic, social, emotional, and physical supports and services to school-age children and youth across the Commonwealth of Virginia. • Out-of-school time: Before school. After school. Vacation periods. Summer. • Services: Technical assistance to school-based/school-linked programs, partner organizations, and policy-makers. – Support and promote high-quality programs to improve outcomes for youth and families. – Support statewide systems to ensure programs are of high quality. 46 Expanded learning opportunities • Expanded learning opportunities (ELOs) offer structured learning environments outside the traditional school day. • Programs before and after school; summer programs; and extended-day, -week, or -year programs. • ELOs provide a range of enrichment and learning activities in various areas: – – – – – Academic support. Mentoring. Arts. Civic engagement. Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). 47 Activities endorsed by VPOST • Academic programs. • Mentoring activities including collaboration among families, communities, and schools. • Hands-on learning. • Financial models of operating ILT programs (e.g., after-school programs) that are affordable, scalable, and sustainable. • Arts. • Civic engagement. • STEM. 48 Benefits and gains • • • • • Increase graduation rates. Boost students’ academic gains. Increase student engagement in learning. Cultivate students’ work-study habits. Improve student behavior and socialemotional development. • Improve school and community connectedness. • Raise aspirations for college. 49 What we know • The research evidence is abundant. • Highly effective before-school, after-school, and summer learning models are plentiful. • Outcomes are broad and deep: increased attendance, academic success, higher graduation rates, reduction in the achievement gap and summer learning loss, safety, engagement in STEM and 21stcentury skills. • Great return on a very modest investment. 50 Conclusion • After-school programs are key to keeping kids safe, helping working families, improving academic achievement, and workforce development. • We continue to support efforts to build capacity for expanded afterschool programs for Virginia’s children and youth. 51 Q & A Discussion 52 Examining Increased Learning Time Practice in Context Dr. Carol K. McElvain Principal TA Consultant American Institutes for Research Examining ILT practice in context • Programs that delineated elements appear to have impact to build: – Stronger self-efficacy. – Interest in school and career. – Engagement. – Relationships with peers and adult leaders. • Areas of programming we looked at in case studies: – College and technical education (CTE). – English language skill building. – STEM. 54 Key elements of strong CTE programs • Emphasis on problem solving—“real world” problems. • Critical thinking. • Professionalism/work ethic. • Oral communication. • Strong teamwork. • For older students: – High school offers technical certifications for students. – Culinary arts, entrepreneurship, carpentry, electrical and mechanical trades, medical (nursing, home health care). – College-bound programs—multiple-year reinforcement, advising, career planning, and appropriate class choices. 55 Case studies: CTE • Belle Fourche Middle School (SD): – “Mind Your Own Business” program. – Career-related skills developed—obtaining a business license, doing a cost analysis, using a checking account, applying for a loan. – Students designed and manufactured a product to sell at a business fair. • Duquesne-West Mifflin Boys & Girls Club (PA): – Students ran a “mini-mall” called The Zone on a street with good foot traffic. – All aspects of mini-mall planned and managed by youth. – Included ordering, food preparation, inventory, stocking, and customer service. • Community Works of Louisiana (LA): – Assessments and personality inventories to explore potential careers. – “Pathway” concept—from choosing high school classes to college. 56 Key elements of strong English language programs • Instructional practices focused on language and academic support: – Focused on the four domains of language development: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. – Intentionally focused on vocabulary development. – Used students’ home language. – Hired specialists for targeted support. • Meaningful inclusion and affirming learning environments: – Intentional outreach to English language learning students. – Addressed social-emotional needs. – Hired staff who had particular skills or expertise in working with English language learning students (community members, bilingual staff, staff with prior experience in English learning). 57 Key elements, English language programs (continued) • Culturally relevant programming. – Incorporated activities to instill cultural pride. • Family and community engagement. – Connected parents and other family members to relevant services targeting immigrant and English language learning families. – Acted as a liaison between families and school. • Adequate professional development for staff to work with English language learning students and families. 58 Case studies: English language • Kindergarten Kids (ID): – Emphasis on building ways for Hispanic students to “love language.” – Intentional methods included concept mapping, pre-teaching, and re-teaching for reinforcement. – Provided students first with “big ideas,” then worked on words in a variety of contexts and formats. • Shorefront Ystars @PS22 (NY): – New English language learning students paired with students who had been in the United States longer and had stronger English language skills (mentors). – Not only built rapport, but gave mentor students a stronger sense of confidence in their own abilities. • OurBridge (NC): – Interest in working with Asian students a key to hiring. – Linguistic tutor works individually with students for short time periods. 59 Key elements of strong STEM programs • Provide opportunities to engage in inquiry-based activities. – Consider ways to use alternate spaces and learning environments. – Design program model/components and activities conducive to STEM learning. – Identify relevant STEM topics. – Secure appropriate STEM resources and supplies. • Community partnerships. – Range and types of partnerships in 21st Century Community Learning Centers STEM programs. – Diversity of roles in STEM partnerships. • Professional development in the content areas. – Provide opportunities for STEM professional development from external providers. 60 Case studies: STEM • Bristol Borough at St. James Parish House (PA): – Leverages strong partnership with the Holy Family University Criminal Justice Department to engage students in forensic science activities and investigations. – Through partnership, students have access to technology to examine hair strands, fingerprints, and saliva. • Red Cloud Indian School (SD): – Program serves students in grades 9–12 in partnership with the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. – Staff members alter the science labs for after-school program, allowing for more creative use of space and self-directed, interest-based projects. • E3 University at P.S. 2 (NJ): – Students in grades 4–8 (many English language learning students) take advantage of proximity to Passaic River and collect and analyze water samples from around Patterson and perform related experiments and activities. 61 Q & A Discussion 62 Wrap-Up Dr. Lydotta Taylor Task 2 Lead REL Appalachia 63 Stakeholder Feedback Survey