It would seem that past Alaska Native/American Indian policies of

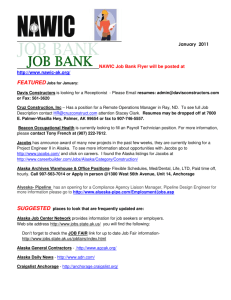

advertisement