A test of parallelism. Presentation at the 10th Laboratory Phonology

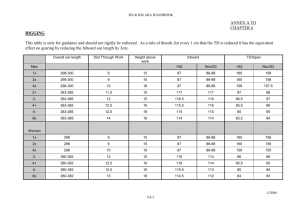

advertisement

Perceptual Organization in Intonational Phonology: A Test of Parallelism J. Devin McAuley1 & Laura C. Dilley2 Department of Psychology Bowling Green State University1 The Ohio State University2 10th Conference on Laboratory Phonology, Paris July 1, 2006 Patterns in prosodic systems Patterns are widespread in prosodic systems Example: Repetition in accentual sequences Why does accentual repetition occur? Ladd (1986): I wanted to read it to Julia. H L HL Other kinds of patterning have been central to phonological theory H L Correspondence Theory (McCarthy & Prince 1995): Patterning arises from Universal Grammar Proposal: Perception provides the basis for patterning in prosodic systems Prosodic patterns In pitch: “…nothing like the full set [of accents] generated by the grammar has ever been documented. For three accent phrases, the typical pattern is either to use the same accent type in all three positions, or else to use one type of accent in both prenuclear positions, and a different type in nuclear position.” (Pierrehumbert 2000: 27) In time? cf. perceptual isochrony (Lehiste 1977) Why are accentual sequences repeated? What mechanisms underlie perceptual isochrony? Perceptual organization Repeating patterns in pitch and time lead to: Perception of structure: grouping and meter Generation of expectations Pitch: H L H L H L … (H* L) (H* L) (H* L) … H (L* H) (L* H) (L* …) Time: … ( * )( * )( * )… (Woodrow 1911, Povel and Essens 1985, Handel 1989) Parallelism Principle “When two or more stretches of speech can be construed as parallel, they preferably form parallel parts of groups with parallel metrical structure.” (cf. Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1983) Parallelism depends on regularity in pitch or in time )L)( )(H* ( L)) (H* H ( (L* H) …) ) ((L* ( )(L* (H) (H* (H* L) )… H L H L H L ……(H*) (L* H L) L) …… … * * * * Parallelism aids in communication * * Creates metrical structure Causes expectations to be generated, drawing attention to important parts of utterances Stimuli and Task 20 target sequences consisted of two disyllabic trochaic words (e.g., worthy vinyl) followed by a final four syllable string that could be organized into words in more than one way (e.g., lifelong handshake versus life longhand shake). 80 filler sequences consisted of 6 – 10 syllables; an equal number ended with a disyllabic or monosyllabic final word. Task: Participants listened to target and filler sequences and reported the final word they heard in each sequence. Condition I: “Pitch” F0 alternated between H and L HL expectancy: worthy vinyl life H L H L HL long hand shake H L “shake” H LH expectancy: worthy vinyl life long hand shake L H H L H L L H “handshake” Condition II: “Duration” F0 was flat; interval between syllables 5, 6 varied weak-strong expectancy: long hand shake worthy vinyl life S W S W S (W) S W “shake” S lengthened strong-weak expectancy: worthy vinyl life long hand shake S W W S W S shortened S W “handshake” Condition III: “Pitch + Duration” F0 alternated between H and L; interval between syllables 5, 6 varied HL + weak-strong expectancy: worthy vinyl life long hand shake H S H S L W H L S W H L S (W) L W “shake” H S lengthened LH + strong-weak expectancy: worthy vinyl life L S H W L H S W L S long hand shake H L H W S W shortened “handshake” Participants One-hundred thirty-eight native speakers of American English attending Ohio State University. Assigned to one of the three prosodic context conditions. Pitch (n = 57) Duration (n = 40) Pitch + Duration (n = 41) Procedure Practice Participants listened to six filler sequences and wrote down the final word they heard. Test Participants listened to 100 sequences (20 targets / 80 fillers) and wrote down the final word they heard. 10 targets paired with a disyllabic context 10 targets paired with a monosyllabic context Target sequence / context pairing counterbalanced across participants. Predictions ‘HL’, ‘weak-strong’, and ‘HL + weak-strong’ expectations (“monosyllabic contexts”) should produce monosyllabic final word reports: e.g., worthy vinyl life longhand shake ‘LH’, ‘strong-weak’, and ‘LH + strong-weak’ expectations (“disyllabic contexts”) should produce disyllabic final word reports: e.g., worthy vinyl lifelong handshake Results 1.0 0.8 Context Disyllabic 0.7 Monosyllabic P(Disyllabic Response) 0.9 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 Duration Pitch Condition Pitch+Duration Perceptual sensitivity analysis Could subjects simply be reporting more disyllabic words across the board? How much prosodic context affects word reports vs. Bias for reporting disyllables vs. monosyllables d' = z(Hits) – z(False Alarms) Hit = Reporting a disyllabic word in a disyllabic context False Alarm = Reporting a disyllabic word in a monosyllabic context Low d' (≈0) if Hits≈False Alarms; Higher d' (> 0 – 4.0) indicates that disyllabic words are more often reported only in disyllabic contexts Results 2 Perceptual Sensitivity (d') 1.8 1.6 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 Duration Duration-alone Pitch Pitch-alone Disyllabic Context Pitch+Duration Pitch+Duration Results 1 0.8 0.6 Criterion (c) 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 Duration-alone Duration Pitch-alone Pitch Di-Syllabic Context Pitch+Duration Pitch+Duration Summary Regularity in pitch and time affected perceived syllable grouping into words More disyllabic responses when prior context favored a disyllabic grouping Both pitch and duration were effective cues to structure; combined cues were most effective Supports the relevance of auditory perception to prosodic phenomena Supports the Parallelism Principle Prosodic regularity is not simply due to “Universal Grammar” Mechanisms underlying Parallelism Listeners generate expectations about upcoming auditory events which affect attention (Jones 1976, McAuley and Jones 2003) Confirming expectation Habituation (“Nothing new…”) Violating expectation Heightened attention (“Here’s something new!”) Parallelism Principle describes a special case of these general processes Patterns lead to maximal violation of expectation and maximally heightened attention at location of a change Intonational phonology: Implications Why do accents tend to repeat? Observation: Narrow focus and/or nuclear position leads to a different accent. Why? Repeating sequences have special status in effectively creating perceptual structure (Parallelism) Change draws attention to important locations What factors limit possible accentual sequences? Fixed inventory of single-toned and bitonal accents (Pierrehumbert 1980) Language-universal principles (cf. Parallelism) + language-specific restrictions (Dilley 2005) Language acquisition Studies of segmentation have focused primarily on local cues to stress and word boundaries An experiment showed that listeners “carry forward” expectations based on perceived parallel structure Infants may use global prosodic structure to develop candidate word segmentations Parallelism provides initial “hook” into prosodic structure Parallelism likely supplements acoustic cues to stress, which are variable, plus phoneme sequence probabilities Conclusions A Parallelism principle was proposed to explain prosodic patterning Experimental evidence supported this principle Parallelism is a special case of general processes involving generation of expectations and allocation of attention These processes help to explain repetition and change in accentual sequences Parallelism may play a role in language acquisition References Handel, S. (1989) Listening: An introduction to the perception of auditory events. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Ladd, D. R. (1986) Intonational phrasing: the case for recursive prosodic structure. Phonology Yearbook 3, 311-340 Lehiste, I. (1977) Isochrony revisited. Journal of Phonetics 5, 253-263. Lerdahl, F. and Jackendoff, R. (1983) A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Jones, M. R. (1976). Time, our lost dimension: Toward a new theory of perception, attention, and memory. Psychological Review, 83, 323-355. McAuley, J. D. and Jones, M. R. (2003). Modeling effects of rhythmic context on perceived duration: A comparison of interval and entrainment approaches to short-interval timing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 29, 11021125. McCarthy, J. and Prince, A. (1995) Faithfulness and Reduplicative Identity, in University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 18: Papers in Optimality Theory. Ed. by Jill Beckman, Suzanne Urbanczyk and Laura Walsh Dickey. Pp. 249–384. Pierrehumbert, J. (2000) Tonal elements and their alignment. In Prosody: Theory and Experiment, M. Horne (ed.), Kluwer, pp. 11-36. Povel, D. J., and Essens, P. (1985) Perception of temporal patterns. Music Perception 2(4), 411-440. Woodrow, H. (1911). The role of pitch in rhythm. Psychological Review, 18, 54-77.