Chapter 3 Checkpoint

advertisement

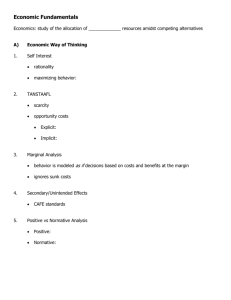

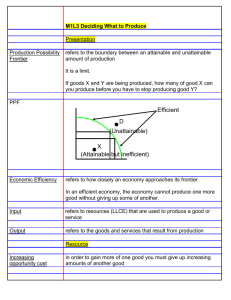

© 2013 Pearson The Economic Problem 3 CHECKPOINTS © 2013 Pearson Checkpoint 3.1 Problem 1 Checkpoint 3.2 Checkpoint 3.3 Problem 1 Problem 1 Problem 2 Problem 2 Clicker version Problem 2 Problem 3 Clicker version In the News Problem 4 Clicker version In the News Clicker version Checkpoint 3.4 Problem 1 Problem 2 In the News © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Practice Problem 1 Table 1 sets out the production possibilities of a small Pacific island economy. Draw the economy’s PPF. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Solution The PPF is the boundary between combinations of goods that are attainable and unattainable. The figure shows the economy’s PPF. The graph plots each row of the table as a point with the corresponding letter. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Practice Problem 2 The figure shows an economy’s production possibilities. Which points are attainable? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Solution The PPF is the boundary between combinations of goods that are attainable and unattainable. Any point on the PPF or below (inside) the PPF is attainable. Any point outside the PPF is unattainable. Point A, B, C, D and E are attainable. Point F and G are unattainable. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Study Plan Problem We can produce all combinations ______. A. on the PPF but not inside or outside the PPF B. inside the PPF but not on the PPF or outside the PPF C. on the PPF and outside the PPF D. inside the PPF and on the PPF © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Practice Problem 3 The figure shows an economy’s production possibilities. Which points are efficient and which points are inefficient? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Solution To be efficient, a point must be attainable. So points F and G are not efficient. Points inside the PPF are not efficient because more goods can be produced at such points. So points D and E not efficient. The only efficient points are those on the PPF—points A, B, and C. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Inefficiency occurs when resources are misallocated or unemployed. Inefficiency occurs at any point inside the PPF. Combinations at points D and E are inefficient. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Study Plan Problem Production efficiency occurs when Figure 1 A. it is not possible to produce more of one good or service without producing less of something else. B. we use the least possible quantity of resources. C. we produce only one good. D. we produce at least possible cost. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Study Plan Problem Which points are inefficient? Figure 1 A. Points F and G only B. Points D and E only C. Points A, B, C, D, and E D. Points A, B, and C only © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Practice Problem 4 The figure shows an economy’s production possibilities. Which points illustrate a tradeoff? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Solution A tradeoff is an exchange—giving up something to get something else. A tradeoff occurs when moving along the PPF from one point to another. So moving from any point on the PPF, point A, B, or C, to another point on the PPF illustrates a tradeoff. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Study Plan Problem A tradeoff occurs when we ____. Figure 1 A. move from a point inside the PPF to a point on the PPF B. move from a point outside the PPF to a point on the PPF C. move from a point on the PPF to another point on the PPF D. move from a point on the PPF to a point outside the PPF © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 In the News Loss of honeybees is less but still a threat Honeybees are crucial for the pollination of almonds in California’s Central Valley. During 2008, 30 percent of U.S. honeybee hives died. Source: USA Today, May 20, 2009 Explain how the loss of honeybees affected the Central Valley PPF. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Solution Honeybees are a resource used in the production of almonds. In 2008, Central Valley farmers were at a point on their PPF. A 30 percent drop in bees hives will reduce the quantity of almonds produced by about 30 percent. With no change in the quantity of other crops produced, the Central Valley PPF will shift inward. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.1 Study Plan Problem A free lunch occurs at ____. Figure 1 A. B. C. D. Points A, B, C, and D Points F and G only Points D and E only Points A, B, and C © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 Practice Problem 1 The table shows Robinson Crusoe’s production possibilities. If Crusoe increases production of berries from 21 pounds to 26 pounds and his production is efficient, what is his opportunity cost of a pound of berries? Does Crusoe’s opportunity cost of berries increase as he produces more berries? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 Solution Production is efficient, so Crusoe produces on his PPF. The opportunity cost of an extra pound of berries is the decrease in the quantity of fish divided by the increase in the quantity of berries as he moves along his PPF in the direction of producing more berries. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 Table 1 tells you that to increase the quantity of berries from 21 pounds to 26 pounds, Crusoe moves from row F to row E. His production of fish decreases from 15 pounds to 13 pounds. To gain 5 pounds of berries, Crusoe must forego 2 pounds of fish. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 The opportunity cost of 1 pound of berries is the 2 pounds of fish forgone divided by 5 pounds of berries gained. His opportunity cost is 2/5 of a pound of fish. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 The opportunity cost of berries increases as Crusoe produces more berries. To see why, move Crusoe from row E to row D in Table 1. The production of berries increases by 4 pounds to 30 pounds and production of fish decreases by 2.5 pounds to 10.5 pounds. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 To increase his production of berries by 4 pounds he forgoes 2.5 pounds of fish. His opportunity cost of 1 pound of berries is 5/8 of a pound of fish. As Crusoe produces more berries, his opportunity cost of a pound of berries increases. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 Practice Problem 2 The table shows Robinson Crusoe’s production possibilities. If Crusoe is producing 10 pounds of fish and 21 pounds of berries, what is his opportunity cost of an extra pound of berries? What is his opportunity cost of an extra pound of fish? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 Solution The figure graphs the data in the table and shows Crusoe’s PPF. If Crusoe is producing 10 pounds of fish and 21 pounds of berries, he is producing at point Z. You can see that Z is a point inside Crusoe's PPF. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 When Crusoe produces 21 pounds of berries, he has sufficient time available to produce 15 pounds of fish at point F on his PPF. To produce more berries, Crusoe can move from point Z toward point D on his PPF and forgo no fish. His opportunity cost of a pound of berries is zero. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 In the News Obama drives up miles-per-gallon requirements Emission levels of new automobiles must be cut from 354 grams in 2009 to 250 grams in 2016. To meet this standard, the price of a new vehicle will rise by $1,300. Source: USA Today, May 20, 2009 Calculate the opportunity cost of reducing the emission level by 1 gram. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.2 Solution By spending $1,300 extra on a new car, you forgo $1,300 of other goods. With a new car, your emissions fall from 354 grams to 250 grams, a reduction of 104 grams. The opportunity cost of a 1-gram reduction in emissions is $1,300 of other goods divided by 104 grams, or $12.50 of other goods. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.3 Practice Problem 1 The table shows an economy that produces education services and consumption goods. If the economy currently produces 500 graduates a year and 2,000 units of consumption goods, what is the opportunity cost of one additional graduate? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.3 Solution By increasing the number of graduates from 500 to 750, the quantity of consumption goods produced decreases from 2,000 to 1,000 units. The opportunity cost of a graduate equals the decrease in consumption goods divided by the increase in the the number of graduates. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.3 The opportunity cost of a graduate equals 1,000 units of consumption goods divided by 250 graduates. The opportunity cost of 1 additional graduate is 4 units of consumption goods. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.3 Practice Problem 2 How does an economy grow? Explain why economic growth is not free © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.3 Solution An economy grows if it expands its production possibilities—if it develops better technologies; improves the quality of labor by education, on-the-job training, and work experience; and acquires more machines to use in production. When resources are used today to produce better technologies, better quality labor, or more machines, they cannot be used to produce goods and services. The cost of economic growth is the goods and services forgone today. Economic growth is not free. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Practice Problem 1 Tables show Tony’s and Patty’s production possibilities. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Who has a comparative advantage in producing snowboards? Who has a comparative advantage in producing skis? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Solution The person with a comparative advantage in producing snowboards is the person who has the lower opportunity cost of producing a snowboard. To produce 5 more snowboards, Tony must produce 10 fewer skis, so his opportunity cost of 1 snowboard is 2 skis. To produce 10 more snowboards, Patty must produce 5 fewer skis. Her opportunity cost of 1 snowboard is ½ a ski. Patty has the lower opportunity cost of producing a snowboard, so she has a comparative advantage in producing snowboards. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Tony’s production possibilities show that to produce 10 more skis he must produce 5 fewer snowboards. So his opportunity cost of producing a ski is 1/2 snowboard. Patty’s production possibilities show that to produce 5 more skis, she must produce 10 fewer snowboards, so her opportunity cost of producing a ski is 2 snowboards. Tony has the lower opportunity cost of producing a ski, so he has a comparative advantage in producing skis. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Practice Problem 2 Tony produces 10 snowboards and 5 skis. Patty produced 5 snowboards and 10 skis. If they specialize and trade, what are the gains from the trade? © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Solution Patty has a comparative advantage in producing snowboards, so she specializes in producing snowboards. She produces 20 snowboards a week. Tony has a comparative advantage in producing skis, so he specializes in producing skis. He produces 50 skis a week. Before specializing, they produce 15 snowboards (Patty’s 10 plus Tony’s 5) and 45 skis (Tony’s 40 plus Patty’s 5). By specializing, they increase their total production by 5 snowboards and 5 skis, which are the gains from trade. They can share the gains by trading 1 ski for 1 snowboard. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 In the News With big boost from sugar cane, Brazil is satisfying its fuel needs Brazil is almost self-sufficient in ethanol. Brazilian ethanol is made from sugar and costs of 83 cents per gallon. U.S. ethanol is made from corn and costs of $1.14 per gallon. Source: The New York Times, April 12, 2006 Which country has a comparative advantage in producing ethanol? Explain why both the United States and Brazil can gain from specialization and trade. © 2013 Pearson CHECKPOINT 3.4 Solution The cost of producing a gallon of ethanol is less in Brazil than in the United States, so Brazil has a comparative advantage in producing ethanol. If Brazil specialized in producing ethanol and the United States specialized in producing other goods (for example, movies or food) and engaged in free trade, each country would be able to get to a point outside its own PPF. © 2013 Pearson