Full Presentation

advertisement

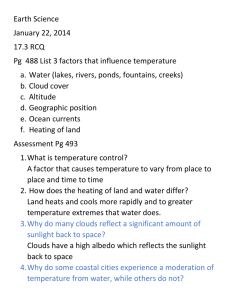

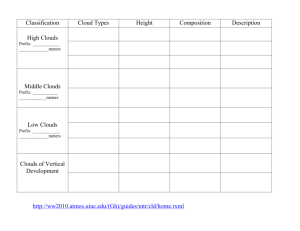

”Tropical Clouds and Cloud Feedback” The importance of radiative constraints Dennis L. Hartmann Department of Atmospheric Sciences University of Washington Seattle, Washington USA Workshop on Large-Scale Circulations in Moist Convecting Atmospheres October 15-16, 2009 Papers online: Google Dennis L. Hartmann Outline • Motivation from AR4 simulations • Radiation-Convection-Dynamics Interaction • Fixed Anvil Temperature Hypothesis (FAT) • Application of FAT to AR4 GCM Simulation Interpretation LW feedbacks positive and comparable magnitude. SW feedbacks positive/negative, and dominate total feedback. SW and LW cloud feedback Net cloud feedback from 1%/ yr CMIP3/AR4 simulations Courtesy of B. Soden Clouds, Convection and Radiation Atmospheric Energy Balance • Atmospheric Energy Balance is Radiative –Convective • Radiative Cooling = Latent Heating + Advection of Energy • Clear-Sky Radiative Cooling is a key parameter. Clear-sky Radiative Cooling and Relaxation: for tropical climatological conditions In the tropical atmosphere, and the in the global atmosphere, radiative cooling approximately balances heating by latent heat release in convection. The global mean precipitation rate is about 1 meter per year, Adiabatic which equals an energy input of about 80 Watts/sq. meter, Heating Requiring a compensating atmospheric radiative cooling of about 0.7 ˚K/day, averaged over atmosphere. -2.0 -1.0 Atmospheric Radiative Cooling Altitude vs Frequency Upper Troposphere Cooling from Water Rotation Lines 50 m 20 m 106.7 mm 5 m Lower Troposphere Cooling from Water Continuum Harries, QJRMS, 1996 The FAT Hypothesis, The Fixed Anvil Temperature Hypothesis. Tropical anvil clouds appear at a fixed temperature given by fundamental considerations of: • Clausius-Clapeyron definition of saturation vapor pressure dependence on temperature. • Dependence of emissivity of rotational lines of water vapor on vapor pressure. Testing the FAT Hypothesis with a CRM. ‘Cloud-Resolving’ Model 1km horizontal resolution Doubly periodic domain 64km x 64km box with uniform SST (28, 30, 32C) Bulk microphysics RRTM radiation model Basically a radiative-convective model in which the Clouds are explicitly resolved at 1km resolution. Run to equilibrium and average last 50 days. Zhiming Kuang’s work: Updated by Bryce Harrop Recreating Kuang & Hartmann (2007) Results Using SAM with CAM 5˚C Radiation • Change the level of clear-sky convergence • Two possibilities – Remove water vapor to lower convergence level – Add more water vapor to raise convergence level • SAM model: Two different water vapor variables – Bulk microphysics – Radiation Altering Water Vapor in the Radiation Code Part I Water vapor change only applied to radiation calculation!! Temperature Base Case Removal Case Reduces emissivity = Less cooling = ? qv, stratospheric Water Vapor (radiation only) Removal of Water Vapor Comparison Base Removal Altering Water Vapor in the Radiation Code Part II Water vapor change only applied to radiation calculation!! Temperature Base Case Removal Case Addition Case qv, Water Vapor (radiation only) stratospheric Addition of Water Vapor Comparison Addition Base Radiative Control In radiative-convective equilibrium in a CRM • If you change SST, cloud temperature remains about the same - FAT • If you change the emissivity of the upper troposphere in the Tropics, you can change the cloud temperature and associated circulation. LW feedbacks positive and comparable magnitude. SW feedbacks positive/negative, and dominate total feedback. SW and LW cloud feedback Net cloud feedback from 1%/ yr CMIP3/AR4 simulations Courtesy of B. Soden Motivation: Why is the Longwave Cloud Feedback Robustly Positive in the AR4 GCMs? • We hypothesize that it is largely due to the fact that tropical high clouds remain at approximately the same temperature as the climate warms • The clouds become higher as the surface warms, but do so in such a way as to remain at approximately the same temperature • If high cloud emission temperature stays constant (or warms less than the surface), then this would lead to a positive cloud feedback, assuming no change in cloud fraction. Predicting level of abundant high cloudiness from clear-sky balance • Input to Fu-Liou code: tropical-mean profiles of temperature and humidity averaged over decades calculate net (LW+SW) radiative cooling profiles • Assume that this radiative cooling is balanced by diabatic subsidence take vertical derivative to get clear-sky UT convergence assume from mass continuity that this is balanced by convective detrainment should see clouds there Mark Zelinka’s Work Dashed: Clouds, Solid: Convergence SRES A2 Ensemble-Mean Radiative cooling 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Static stability (T/θ)dθ/dp 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Diabatic ω 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Diabatic convergence 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 SRES A2 Ensemble-Mean CTT warms ~1 K Sfc Warms ~3 K Upper Troposp here warms ~6 K Attempting to Quantify Contribution of FAT to Longwave Cloud Feedback First calculate ΔLWCF, then use radiative kernel technique to estimate LW Cloud Feedback Very difficult because cloud properties are not saved and so cannot calculate radiative effect of clouds Compare ΔLWCF for ‘FAT’ and ‘FAP’ • FAT ΔLWCFtropics = Δfhi(OLRclr– OLRhicld) – fhiΔOLRhicld – floΔOLRlocld + fΔOLRclr • FAP ΔLWCFtropics = Δfhi(OLRclr–OLRhicld) – fhiΔOLRhicld – floΔOLRlocld + fΔOLRclr assuming that OLRhi = σCTT4 in which the CTT increases as much as the temperature at a fixed pressure level (the initial cloud-weighted pressure) • Finally, apply the cloud mask as explained in Soden et al. 2008 to convert ΔLWCF to LW cloud feedback Actual ENSEMBLE MEAN LW CLOUD FEEDBACK Actual FAP FAT FAP minus Actual FAT minus Actual Conclusion. • Radiative Convective Equilibrium, constrained by Clausius Clapeyron and basic radiation physics, seems to be a strong constraint on the depth of the convective layer in the Tropics. • One result of this is that the detrainment layer in the Tropics tends to have a nearly fixed temperature as the climate changes, or a nearly fixed anvil cloud temperature. • Another result of this is that climate models tend to give a relatively strong positive cloud longwave feedback. • Also, the Hadley Cell will deepen in pressure thickness with global warming. High Cloud-weighted P Red: 1:1 line, with nonzero yintercept Each x is a decadal mean UT Convergence-weighted P High Cloud-weighted T Red: 1:1 line, with nonzero yintercept Each x is a decadal mean UT Convergence-weighted T Radiative cooling 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Static stability (T/θ)dθ/dp 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Diabatic ω 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Diabatic convergence 2000-2010 2070-2080 2090-2100 Attempting to Quantify Contribution of FAT to Longwave Cloud Feedback First calculate ΔLWCF, then use radiative kernel technique to estimate LW Cloud Feedback Very difficult because cloud properties are not saved and so cannot calculate radiative effect of clouds Decomposing the change in LWCF for cloud fraction (f) and cloud properties • If OLR = f OLRcld + (1-f)OLRclr then LWCF = OLRclr – OLR = f (OLRclr – OLRcld) • ΔLWCF = Δf (OLRclr–OLRcld) + f ΔOLRclr – fΔOLRcld Actual HAD CM3 ΔLWCF Sum Δf(OLRclr – OLRcld) – fΔOLRcld fΔOLRclr Sum minus actual Decomposing the change in LWCF • LWCF = OLRclr – OLR = f(OLRclr – OLRcld) • ΔLWCF = Δf(OLRclr–OLRcld) + fΔOLRclr– fΔOLRcld • This term dominates, but not because of warming or cooling high clouds, but apparently because of different abundances of high vs. low clouds (see next slide) HAD CM3 ΔLWCF<<0 due to ΔOLRcld>>0 Dashed: 2000-2010 Solid: 2090-2100 HAD CM3 ΔLWCF>>0 due to ΔOLRcld<<0 Another ΔLWCF decomposition • Let’s assume we can break OLRcld and f into contributions from high and low clouds. • We do this separation only in the Tropics • Rather than trying to pretend like we know the effective high and low cloud fractions, lets assume that the high cloud-weighted temperature is a reasonable estimate of the high cloud emission temperature and that the low cloud emission is the same as clear-sky emission. • Then we can determine what fhi and flo must be such that fOLRcld = fhiOLRhicld + floOLRlocld • [1] LWCF = OLRclr - OLR = f(OLRclr – OLRcld) • [2] ΔLWCF = Δf(OLRclr – OLRcld) + fΔOLRclr – fΔOLRcld • If we assume that f and OLRcld can be broken into a component from high and from low clouds: • [3] fOLRcld = fhiOLRhicld + floOLRlocld, where flo is the fraction of area covered by low clouds that are not covered by high clouds • Using a cloud-weighted temperature for clouds that are between the freezing level and the tropopause as CTT, we write [4] OLRhicld = σCTT4 • Using f = fhi + flo, we can solve [3] for fhi: • [5] OLR OLR cld locld f f hi OLR OLR hicld locld where OLRcld is given by [1], OLRhicld is given by [4], and we assume OLRlocld = OLRclr • [6] ΔLWCF = Δfhi(OLRclr– OLRhicld) – fhiΔOLRhicld – floΔOLRlocld + f ΔOLRclr So the formulas are…. • ΔLWCFtropics = Δfhi(OLRclr– OLRhicld) – fhiΔOLRhicld – floΔOLRlocld + f ΔOLRclr • ΔLWCFextra-tropics = Δf(OLRclr–OLRcld) – fΔOLRcld + fΔOLRclr Predictions from Clear-Sky Radiative Cooling • In the Tropics we should see two or three levels of cloud. – Boundary layer cloud - from strong radiative cooling of moist, warm low level air - H2O continuum – High cloud from strong cooling under tropopause by rotation bands of H2O – Middle cloud from 6.7 micron V/R band MODIS Temperature-Optical Depth Histogram Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean Three Levels of Cloud Tropopause High High-Anvil and Cirrus Clouds Middle Low MiddleCongestus Low Cumulus+ Stratocumulus Optical Depth Kubar et al. 2007 Fundamental energy balance in atmosphere is: Convective heating = Radiative Cooling Question is, Which places a more fundamental Constraint on the climate system in the tropics? Answer: In the deep tropics radiative cooling, particularly in clear skies, may provide a more fundamental prediction of the depth of the convective layer. First Law of Thermodynamics T T T J t u x v y S p c p In Tropics ~ J Spcp Using continuity in pressure coordinates J gV p p S p c p Fact: The radiatively-driven divergence in the clear regions is related to the decrease of water vapor with temperature following the Clausius-Clapeyron relation and the consequent low emissivity of water vapor at those low temperatures. Fact: 200 hPa Convective outflow and associated large-scale divergence near 200 hPa are both associated with radiatively-driven divergence in clear skies. Hypothesis: The temperature at which the radiatively-driven divergence occurs will always remain the same, and so will the temperature of the cloud anvil tops. t>1 9% 22% 10% Use Cloudsat to detect cloud tops and AMSR to estimate precipitation rate Heavy rain is 90th Percentile, 10% of frequency, but ~50% of total rainfall. West Pacific East Pacific Kubar & Hartmann 2008 Use Cloudsat to detect cloud tops and AMSR to estimate precipitation rate Heavy rain is 90th Percentile, 10% of frequency, but ~50% of total rainfall. Kubar & Hartmann 2008 Why should convection stop/detrain at a fixed temperature? Vapor pressure depends only on temperature, and decreases exponentially as T decreases with altitude. Emissivity (radiative relaxation time) depends most importantly on vapor pressure. Temperature where water vapor emissivity becomes small is only weakly dependent on relative humidity and pressure. Heating of air by condensation also becomes small at this temperature Testing the FAT Hypothesis in a model. Larson and Hartmann (2002a,b) Model Study: MM5 in doubly periodic domain a) 16x16 box with uniform SST (297, 299, 301, 303K) b) 16x160 box with sinusoidal SST c) 16x16 box with uniform SST and rotation. Clouds and circulation are predicted Clouds interact with radiation Basically a radiative-convective model with parameterized convection, in which the large-scale circulation is allowed to play a role by dividing the domain into cloudy (rising) and clear (sinking) regions. Radiative Cooling in non-convective region for SST’s ranging from 297K to 303K. From Larson & Hartmann (2002a). The temperature of the 200 hPa surface increases about 13K, while the surface temperature rises 6K. The temperature at which the radiative cooling reaches -0.5 K/day remains constant at about 212K. The temperature at which the visible optical depth of upper cloud reaches 0.1 remains constant at about 200K. Cloud Fraction versus Air Temperature 6˚C CRM in Rad/Conv. Equilibrium 28˚C, 30˚C and 32˚C SST Kuang &Hartmann, J. Climate 2007 Cloud Fraction vs Air Temp. vs Pressure Stratospheric Transport and Exchange 1. Apply upward motion of Brewer-Dobson Circulation. 28, 30, 32C 30C +BDC Test Impact of Radiation Same SAM framework as Kuang & Hartmann • Alter the water vapor that the radiation code sees to change the emissivity of the upper tropical troposphere. • Expect that increasing upper tropospheric radiative cooling vapor will cool the average cloud tops, and vice versa. Bryce Harrop’s work Divergence Calculations Subsidence warming = radiative cooling Comparing CAM and RRTM Radiation Codes Comparing CAM and RRTM Radiation Codes Continued Convergence computed from clear-sky radiative cooling, and Cloud fraction from MODIS plotted versus air temperature (solid) for West Pacific (WP) and East Pacific (EP) Good agreement between clear-sky divergence and cloud fraction. Kubar et al. 2007 217K 221K et al (2007) MODIS Anvil Top vs Convergence Kubar Temperature Kubar et al. 2007 Radiation Code Adjustments: Comparing Weighted Temperatures this study Moist Thermodynamics • Double the Latent Heat of Fusion • Two Possibilities: – Lift the parcel – Warm the parcel Doubling Latent Heat of Fusion Comparison Radiation and Lf Adjustments: Comparing Tconv and Tcld 2x Lf 2x Lf Conclusions • When the radiation is changed, the cloud profile adjusts so that the cloud amount peaks near the level of clear-sky convergence. • A relationship exists between convergence weighted and cloud weighted temperatures. AR4 Climate Simulations Robust Longwave Cloud Feedback • All AR4 models produce a similar positive longwave cloud feedback, compared to the large variability in shortwave cloud forcing. • Can basic constraints like saturation vapor pressure and radiative cooling explain this consistency in the models? Mark Zelinka’s work Is any of this believable? • It is likely that some portion of Δfhi is actually including information about changes in the emission temperature of high clouds as well. • Because we enforce OLR OLR cld locld f f hi OLR OLR hicld locld any error in our estimate of OLRhicld or OLRlocld will be subsumed into fhi (and by extension flo) • This could result in the ΔLWCF term due to Δfhi being overestimated and the ΔLWCF term due to ΔOLRhicld being underestimated • Would like a good method of assessing sensitivity to our assumptions – fhiΔOLRhicld Δfhi(OLRclr – OLRhicld) f ΔOLRclr ENSEMBLE MEAN – floΔOLRlocld ΔLWCF Δfextra-tropical(OLRclr – OLRcld) – fextra-tropicalΔOLRcld Tropical-Mean Results • Varying degrees of agreement between UT convergence and level of high cloud abundance in models • In all models, both convergence- and cloud-weighted pressure (temperature) decrease (VERY slightly increase) in a nearly 1:1 fashion, but with a nonzero y-intercept (see previous point) • Tropical mean UT convergence and high cloud amount decrease slightly over the course of the 21st century (enhanced static stability out-pacing enhanced radiative cooling – see previous slide) – Can this explain Trenberth and Fasullo’s results about decreases in cloudiness allowing for more absorbed shortwave (next slide)? – Also, if high cloud coverage strongly impacts absorbed shortwave, and static stability vs. radiative cooling determines high cloud coverage, then this implies some dependency of SW cloud feedback on lapse rate feedback (at least in the tropics) • Those models with larger (negative) lapse rate feedback should tend to have larger positive (or less negative) SW cloud feedback due to this effect because strong increases in static stability will cause strong decreases in high cloud cover (I guess it depends on the importance of high clouds changes for SW cloud feedback) Issues (1 of 2) • • Clouds plotted in previous figures are total cloud fraction in each pressure bin reported by the model: There is no information about cloud optical properties, nor does it provide information about cloud tops, which are emitting to space. Can look at ISCCP simulator output from models that have participated in CFMIP, but – there are no CO2 scenarios, just 2XCO2 runs with slab oceans – The ISCCP pressure bin resolution is inadequately poor (7 vertical bins) • • • Have done simulations with the GFDL model in aquaplanet mode at .5x, 1x, 2x, and 4x CO2 using the ISCCP simulator – results look similar to here, but with more dramatic warming of high clouds / UT convergence and more dramatic decrease in high cloud coverage more dramatic because of factor of 8 variation in CO2? To what degree should model clouds be collocated with the UT diabatic convergence? Probably depends on details of each model’s convective parameterization (detrainment based on neutral buoyancy?). Very thin stuff near tropopause probably unrelated to detrainment – but we don’t know how much of that type of cloud is represented in these profiles Still need to show that the prevailing thought that detrainment occurs once the parcels reach neutral buoyancy is either incorrect or is consistent with this – if Issues (2 of 2) • • • Probably should be running the Fu-Liou code for each lat, lon, & season rather than just for tropical-mean annual-mean profiles currently working with Marc to run Fu Liou code more efficiently than I have been (currently have a Matlab script that calls the fortran code) Very difficult to be quantitative: can only say that – in all the models – the entire cloud profile rises vertically but as a function of temperature the cloud profile stays nearly constant (warms slightly). (How realistic is the cloudweighted temperature as a proxy for CTT?) Two issues with using tropical-mean temperature and humidity profiles as input to the Fu-Liou code – 1. mean profiles calculated from clear-only regions will likely be different (certainly drier) than those calculated from both clear and cloudy this will affect the shape and magnitude of UT convergence (need to assess sensitivity) – 2. The presence of clouds alters the radiative cooling rates substantially. This is much more difficult to take into account in the radiation code, since one needs to know more about the cloud properties than is provided in the AR4 diagnostics. It is not clear to me to what extent real-world UT detrainment is affected by clouds in the surrounding regions altering the radiative cooling rate. Rainrates from two different algorithms. TOP: Satellite-derived method, based on cloud top temperature; BOTTOM: Derived from Microwave Sounding Unit, (Figure from Berg et al. 2002) Modeling Tropical Convection in a Box or on a Line. For this study we will use the SAM model from CSU. Khairoutdinov and Randall (2003) The first set of experiments will be from a 3D doublyperiodic model run with fixed forcing in a dx=1km 256km x 256km domain with 64 levels, also use 2D version. The dynamics are anelastic, the radiation is that of the NCAR CCM. The cloud physics scheme has conservation equations for total water and precipitating water, apportionment among types is based on temperature. Note that 3D model has 5m/s shear imposed. 3-D Model External forcing from Reanalysis for EP and WP, but use same SST of 302.49K Top Heavy Bottom-Heavy converting cloud in to precip. Model Movie Use 2-D to Test Sensitivity • Use same SAM model in 2-D version • Apply SST sinusoid to force circulation. • No external forcing other than SST and Radiation MODIS Temperature-Optical Depth Histogram Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean Three Levels of Cloud Tropopause Thin Anvil Thick High-Anvil and Cirrus Clouds Middle Low MiddleCongestus Low Clumulus+ Stratocumulus Optical Depth Kubar et al. 2007 We will see that, with same microphysics 2-D model has similar strengths and weaknesses as 3-D Model • Decent thick and thin cloud distributions, but • Anvil clouds (intermediate optical depths) are too few and do not have correct dependence on precipitation rate. Validation Methodology • Average over comparable subdomains - about 100km square sub-domains to define local precip and cloud properties. • Use precipitation rate as an independent variable. • Tests relationship of cloud stuff to precipitation rate • Works equally well for column model, regional model, global model and data. • Don’t have to adjust anything about methodology in going from 3D to 2D Test 3-D & 2-D run against Satellite Data a la Kubar et al. 2007 2-D Base MODIS AMSR Thick Cloud - about right Lopez et al. 2007 Test 3-D run against Satellite Data a la Kubar et al. 2007 Anvil Cloud Error 2-D case Lopez et al. 2007 Test 3-D run against Satellite Data Albedo & OLR PDFs - Domain Mean Anvil Cloud Signature Anvil Cloud is Missing Lopez et al. 2007 Use 2-D to Test Sensitivity Summary: • We can increase ice cloud by reducing ice sedimentation, but this also increases thick cloud unrealistically. • Increasing the Autoconversion/Accretion rate reduces the thick cloud preferentially. • AA rate preferentially controls water cloud, which is responsible for thick cloud fraction. • Accretion is more important than autoconversion. Adjustments suggested by 2-D Sensitivity Tests • We need to increase ice and decrease water to get the right albedo distribution of cold cloud. • This means decreasing ice sedimentation, while increasing accretion of cloud water. Use 2-D to Test Sensitivity Multiple Changes • NOSED - set ice sedimation velocity to zero, but lower threshold for autoconversion of ice by a factor of 100. • AALIQN - increase liquid water accretion rate by factor of N. • NOSEDAALIQ5 - NOSED, plus increase liquid water accretion by factor of 5. Multiple Changes to Cloud Physics 2D Results 2-D Base Thick Cloud Lopez et al. 2007 Multiple Changes to Cloud Physics - 2D Anvil Cloud 2-D Base Lopez et al. 2007 Use 2-D to Test Sensitivity Multiple Changes • We found a set of cloud physics parameters that produces better anvil cloud amounts and maintains the observed amount of thick cloud as a function of rain rate NOSEDAALIQ5. • Let’s put these back in the 3-D West Pacific run and see what happens. Improvement! • Cloud Forcing looks more reasonable. But most is thin cloud, and out highofcoverage Cloud fraction climbs sight! of thin cloud may not be unreasonable for the conditions of the simulation. Lopez et al. 2007 Conclusions • Satellite data can be used to effectively test CRM cloud simulations, and GCM’s too. • It is very effective to do the test as a function of rain rate. • Something approaching the observed behavior of convective cores, anvil clouds and thin clouds can be achieved with judicious tuning of a simple bulk scheme. • Work continues. . . Multiple Changes to Cloud Physics - 2D Thin Cloud 2-D Base Lopez et al. 2007 Test 2-D run against Satellite Data a la Kubar et al. 2007 Thin Cloud Not bad 2-D case 3D WP 3D EP Lopez et al. 2007 Model Clouds too Cylindrical General Approach • Focus on Pacific ITCZ regions • Observe and model same regions. EP &WP • Average over comparable subdomains about 100km square subdomains to define local precip and cloud properties. • Use precipitation rate as an independent variable. Testing the Relative Roles of Radiation and Latent Heating in Determining the Temperature of Tropical Cloud Tops Bryce Harrop Clouds and Radiation in the Tropics • Greatest uncertainty in clouds • Changing cloud forcing can drive changes in worldwide circulations LWCF = Fclear - Ftotal Strong COLD LWCF Weak LWCF WAR M SWCF = Stotal - Sclear Strong SWCF Weak SWCF Hartmann et al (2001) Hartmann et al (2001) Temperature Dependent Clear-sky Convergence at 200hPa Anvil Detrainment at 200hPa Fixed Anvil Temperature Hartmann & Larson (2002) PULL vs PUSH • PULL Mechanism – Clear-sky convergence level determines height of clouds • PUSH Mechanism – Buoyancy determines height of clouds Hartmann & Larson (2002) Kuang & Hartmann (2007) Xu et al (2007) >300km L G A E R M U 150-300km E M D I S M A L 100-150km Future Work • How do the moist thermodynamics influence the cloud level? • Is there a relationship between Tconv and Tcld when we change the moist thermodynamics? • Can we modify the moist thermodynamics in such a way that the cloud will reach a different level than the clear-sky convergence? Acknowledgements • Dennis Hartmann • Peter Blossey • Grads 08 Questions? Greenhouse Effect Sensitivity of OLR to Water Vapor 50 m 20 m 10 m Harries, QJ, 1996 5 m Atmospheric Radiative Cooling Altitude vs Frequency Upper Troposphere Cooling from Water Rotation Lines 50 m 20 m 106.7 mmicron 5 m Lower Troposphere Cooling from Water Continuum Harries, QJRMS, 1996 MODIS Temperature-Optical Depth Histogram Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean Three Levels of Cloud Tropopause High High-Anvil and Cirrus Clouds Middle MiddleCongestus Low Cumulus+ Stratocumulus Low Optical Depth Kubar et al. 2007 Rotational Lines of Water Vapor and UpperTropospheric Cooling Total Beyond 18.5m --> Cooling efficiency of atmosphere declines in upper troposphere because of lack of water vapor to emit and absorb radiation. Recreating Kuang & Hartmann (2007) Results Using SAM with CAM Kuan-Man Xu, Personal Communication Dr. Kuan-Man Xu NASA Langley Research Center Analysis of New Data March 2003-November 2004: Aqua. • MODIS optical depth and cloud top temperature - 5km data • AMSR rain rates and column vapor. • Collocated three-day, 1-degree, averages • MLS upper tropospheric humidity: Aura • GPS upper tropospheric temperature profiles Regions of Interest Fig 1. Ensemble SSTs for March 2003-November 2004 West Pacific Central Pacific East Pacific ▪Latitude band of 5ºN-15ºN allows focus to be almost exclusively on convective areas, even in the East Pacific Cloud as a function of rainrate R A I N R A T E WEST CENTRAL EAST Temp-Opt Depth histograms as a function of rainrate (MODIS/AMSR). Rain Rate/Anvil Cloud Area More high cloud per unit of rain in the warmer West Pacific. -3C +20% Modifying the Fixed Anvil Temperature Hypothesis • Cloud Top Temp. 218-216K ( -3C) as SST 27C-30C ( +3C) • Cloud Fraction from 20-40% • Relative humidity ~ high cloud fraction es~ -20% for T~ -3C (es =Saturation Vapor Press.) RH ~ 20%, so e ~ (RH•es) ~ 0 at median anvil level. • Can conclude anvil cloud occurs at fixed e, or fixed T if RH constant. Relative Humidity Profiles From MLS and AIRS and reanalysis for the Western Pacific (WP) Central Pacific (CP) and Eastern Pacific (EP) MLS humidity above 316mb, Temps. from GPS. WP EP with WP humidity EP Fixed Anvil Temperature Hypothesis • Cloud Top Temp. 218-216K ( -3C) as SST 27C-30C ( +3C) • Cloud Fraction from 20-40% • Relative humidity ~ high cloud fraction es~ -20% for T~ -3C (es =Saturation Vapor Press.) RH ~ 20%, so e ~ (RH•es) ~ 0 at median anvil level. • Can conclude anvil cloud occurs at fixed e, or fixed T if RH constant. Conclusions: The favored temperature for tropical anvil cloud tops should remain approximately constant during climate changes of reasonable magnitude. FAT Hypothesis. The emission temperature of the rotational lines of water vapor should also remain approximately constant during climate change. These assertions imply relatively strong water vapor and IR cloud feedback, all else being equal. Hartmann and Larson, GRL, 2002. Some Remaining Questions: How do tropical cloud albedos respond to climate change? Will the area occupied by tropical convection change with climate? If so, how? How do tropical convective clouds interact with other cloud types like marine boundary layer clouds? What will happen at the tropical tropopause? Will it get warmer or colder and what will this mean for climate? Global models should be able to get FAT right, but do they? Fin Greenhouse Effect BB Curve minus OLR 50 m 20 m 10 m 5 m Harries, QJ, 1996