Chapter 12 and 13 Powerpoint - Madison Central High School

advertisement

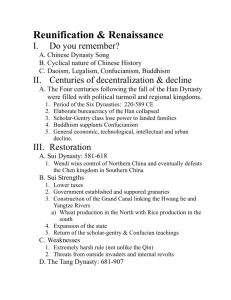

CHAPTERS 12 AND 13: RENAISSANCE AND SPREAD OF CHINESE CIVILIZATION Sui, Tang, and Song Dynasties & Sinification Chinese Renaissance After the fall of the Han dynasty in the 3rd century C.E., it took China roughly 400 years to recover economically and culturally. These 400 years can be viewed as a type of Chinese “Middle Age”, sandwiched between the classical era and the Renaissance of the next three dynasties (Sui, Tang, and Song). Chinese Urban Prosperity Nowhere was this renaissance seen more clearly than in the great cities of China. By the 8th century, China boasted at least a dozen cities with over 1 million people (No cities in Europe, Africa, the Middle East or the Americas could claim even one). As always, these cities served as the centers for wealth, artistic movements, great construction, and political concentration of power. Hangzhou and Kaifeng Hangzhou bridges, canals, and religious structures Chinese pagoda of Kaifeng Sui dynasty (589-618) #1&2 This dynasty arose under the leadership of Wendi, a powerful landlord of noble birth. He was able to secure his power base by negotiating with neighboring nomadic commanders and offering them land and titles in return for their service. He neglected the Confucian scholar-gentry class and won support from the peasantry by lowering taxes and establishing granaries throughout the empire to help in case of flood, drought or famine. Rule of Yangdi (#3) End of Sui Dynasty Eventually Wendi is murdered by his son Yangdi. He was overly fond of luxury and extravagant construction projects like the Grand Canal. Failed military campaigns also led to widespread revolt of his rule. The Grand Canal The Tang Dynasty (#4) Yangdi’s disastrous decisions were averted by one of his ablest generals, Li Yuan, the Duke of Tang. He helped lay the foundation for the golden age of the Tang dynasty. The first thing he did was use military force to secure China’s borders. He extended the empire deep into central Asia (map on p.258), repaired portions of the Great Wall, and secured frontier armies for the empire through a harsh hostage system. Rebuilding the bureaucracy (#6) Despite Wendi’s efforts to weaken the bureaucracy, his son Yangdi (last Sui emperor) and emperors from the Tang dynasty took great efforts to rebuild the bureaucratic structure of China. The Tang emperors needed bureaucrats (also called scholar-gentry) to govern the huge expanding empire they created. Though aristocrats (large landowners) still held power, most of the positions in the executive level of government were held by the scholar-gentry. Civil Service Examination System (#8) The Ministry of Rites was in charge of administering the examination system. High government offices could be gained only by passing exams in Confucian philosophy, law, or the more challenging literature. Those who passed the latter earned the title of jinshi and all its privileges Xu Guangqi, Jinshi (p.261). official (1562) Buddhism’s growth in China (#10) From the Han dynasty up until the Tang dynasty, Buddhism’s popularity continued to grow in China. New strands of Buddhism emerged in China to appeal to different classes. The pure land strain of Mahayana Buddhism and Zen Buddhism were the two most common. Chinese rulers built monasteries and sent ambassadors to India to bring back Buddhist texts and relics. Empress Wu even tried to elevate Buddhism to the status of official state religion. She commissioned paintings and sculptures (p.263), and constructed monasteries and pagodas. By the mid-9th century, there were almost 50,000 monasteries and hundreds of thousands of Buddhist monks and nuns in China. Anti-Buddhist Backlash (#11) Confucian rivals, threatened by the faith’s growing power, began an all-out attack on the religion. Buddhism was targeted as an “alien” faith, since it came from India, even though the Buddhism practiced in China was much different from the original religion taught by the Buddha. Most importantly, Confucian scholars convinced Tang rulers that the Buddhist monastic community was an economic threat to the empire, since the monastic lands and resources could not be taxed. As a result, the regime lost tons of revenue. This had to change. Anti-Buddhist Backlash (#11) Under Emperor Wuzong (Tang dynasty), open persecution of Buddhism began. Buddhist monasteries and shrines were destroyed and thousands of monks and nuns had to abandon their monasteries and return to civilian life in order to be taxed. Monastic lands could again be taxed and some lands were taken away and given to landlords. Neo-Confucianism During the Song dynasty we see a revival of Confucian thought and principle. Many of the scholar-gentry class stressed the need for a return to Confucian morality and personal virtue, thus we see the birth of neo-Confucianism (new Confucianism). According to neo-Confucianists, virtue was attained only through knowledge gained by book learning and through contact with men of wisdom and high morality. In this way, the good nature of humans was cultivated and superior leaders, fit to govern, could be developed. A huge emphasis was placed on tradition and hostility to foreign influences, which ultimately stifled innovation and critical thinking among the Chinese. Neo-Confucianism By the 11th century, the Song dynasty was weakening due to invasions, costs to protect their borders and economic waste from the scholar- gentry class. Despite the hold that neo-Confucianists had on the upper levels of government, by 1070, a chief minister named Wang Anshi tried to reform China through several techniques (p.266-267) (#16) By 1085 however, a new emperor has come to the throne. He was manipulated by the neo-Confucianists and many of Wang Anshi’s reforms were undone. Tang and Song Prosperity: The Basis of a Golden Age (#17) During these dynasties, there is a major shift in population density from the north to the south. In order to improve communication, transportation, and trade between the regions, the Grand Canal is constructed. The canal linked the northern millet growing areas to the rice producing centers in the south. The canal made it possible to transport armies to the south for defense and helped prop up the north with food production from the south in order to avoid famine. Naturally, we can see why it was so important to Chinese rulers. In all, more than one million forced laborers died during its construction. Commercial Expansion (#19) Tang expansion into central Asia reopened many of the Silk Road routes that had been neglected for centuries. The development of Chinese sea commerce during this time was impressive. Spearheaded by Chinese junks, massive commerce ships, Chinese merchants became the most dominant force in the Asian seas. Chinese Junk Commercial Expansion (#20) The expanding market centers of the Tang and Song era were regulated by the government. Merchants specializing in products of the same kind formed guilds. Credit vouchers, known as “flying money” were established so that merchants could present them for reimbursement at the city of their destination. In this manner, merchants did not have to carry large sums of money, and the danger of robbery was greatly reduced. Family life in the Tang and Song Eras (#23 and 24) The Chinese family continued to resemble that of the classical Chinese culture, with male domination being at the center. Women’s position improved drastically during the Tang and early Song eras, but then fell off drastically during the late Song era. Obedience amongst children was paramount with beheadings and hard labor prescribed to disobedient children. A very elaborate process of arranged marriages emerged with professional go-betweens who would negotiate dowries for the families. Women’s Deteriorating Status (#24) With the rise of neo-Confucianism, women’s rights steadily declined. The woman’s role as a homemaker and mother was reasserted. Increased confining of women to the home rose. Widows were discouraged from remarrying. Neo-Confucianists attacked Buddhists for promoting career alternatives for women like scholarship and the monastic life. Women were excluded from education that would allow them to enter civil service and laws were drafted that favored men in inheritance and divorce. Footbinding (OUCH!!) (#25) Footbinding is the one clear example of women’s decreased status in China. Grown out of the taste of one Tang emperor, this practice is widely adopted by upper class Chinese. It reinforced the women’s position in the house by making mobility very painful and difficult. Footbinding process Chapter 13: The Spread of Chinese Civilization Sinification – the extensive adoption of Chinese culture. In chapter 13, the text deals with various ways in which Japan, Korea, and Vietnam underwent this process. •*Taika reforms (646 CE) – Attempts to remake the Japanese monarch into an absolutist Chinese-style emperor; included attempts to create professional bureaucracy & peasant army •Taika reforms failed; the aristocracy returned to Japanese traditions •*Bushi – regional warrior leaders in Japan; ruled small kingdoms from fortresses; administered the law, supervised public works projects, and collected revenues; built up private armies (Samurai) •Similar to Feudalism in Europe – local nobles carved out estates and reduced the peasants to serfdom A Feudal Comparison •Bakufu – Military government established in Japan. It retained an emperor for symbolic reasons, BUT the real power resided in military government and samurai. •Shoguns – Military leaders of the Bakufu A Feudalism Comparison Samurai Samurai warriors were the military elite of Japanese society. Their lives were governed by strict codes of conduct (known as bushido) and loyalty to their lords was paramount in that code. The code was so strictly enforced that samurai would rather die than dishonor the code (sepukku). Korea’s Sinification (#15) Korea, of all China’s neighbors, was the most open to sinification. 1) They fully embraced Buddhism from the Chinese missionaries that brought it to the peninsula, building monasteries and pagodas 2) Chinese writing was introduced to Korea 3) A unified law code that was patterned after that of Han China was imposed 4) Universities were established to teach Confucian classics and train youth of Korea in hopes to form a Chinese-style bureaucracy, though this never caught on. Korea’s Sinification (#15) For the next 700 years, sinification in Korea expanded greatly. 1) Ambassadors were regularly sent to the Chinese court to collect Chinese texts and the latest fashions of court dress and etiquette, which would be copied by the Korean imperial court. The tributary system allowed privileged access to Chinese learning, art, and manufactured goods. Korean scholars studied at Chinese academies and purchased scrolls and literature to fill they libraries back home. Korea’s Sinification (#17) On top of political organization, trade, and education, sinification of Korea extended heavily into its culture. 1) Korean cities were modeled after the Chinese gridstlye layout with parks, lakes, and markets. 2) Korean artwork and monasteries were modeled after Chinese styles, and in case of the former, they outdid their Chinese counterparts, producing the finest pottery in Asia. Vietnam’s Sinification (#19) Overall, the people of Nam Viet (“people of the south”), were fiercly independent. Map on p.294. As a result, they continually fought against China’s expanding influence into their region. Through intermarriage with the Khemers (Cambodians today) and Tais (Thai peoples), they had created their own distinct culture that was more alligned with southeast Asian patterns instead of Chinese. For example, the Nam Viet had their own distinct language, they favored the nuclear family instead of the extended family of the Chinese, and women in this society have had historically more freedom than their Chinese counterparts. Vietnam’s Sinification (#20) By 100 B.C.E., the Han dynasty had conquered Vietnam and began the process of sinification. 1) Vietnamese elite attended Chinese-style schools and learned Chinese script and memorized writings of Confucius. 2) They adopted the examination system to attain high post positions in government. 3) Chinese agricultural techniques were introduced, such as terraced farming, leading to huge agricultural productivity. 4) Over time, the Nam Viet adopted the Chinese extended family patterns and took to venerating their ancestors like the Chinese. Vietnam’s resistance (#21) Over time, the Vietnamese aristocracies disdain for their Chinese overlords grew into outright revolt. It does not hurt to mention that the Chinese also viewed the Vietnamese as backward and barbaric and therefore, treated Vietnamese rulers in this fashion. Vietnamese peasantry was never fully exposed to Chinese ways, and therefore loathed their foreign rulers. They began calling for their local lords to rebel against Chinese rule. This call for rebellion was eventually answered by the Trung sisters. Their role in leading this revolution testifies to the freedom Vietnamese women exercised in this society. In fact, women were the main group behind the revolution, fearing the Confucian codes of subordination and almost sub-human Vietnamese independence (#22) The Vietnamese independence movement was aided by the great distance they were from major Chinese imperial centers and the mountain barriers that created nightmare conditions for the Chinese to supply an army against them. Taking advantage of the weakening Tang dynasty, the Nam Viet peoples launched a massive rebellion shortly after Tang fall in 907 C.E. By 939C.E., they had won their independence and would keep it until conquests by the French in the 19th century. Ultracivilized: Japanese Courtly Life Without going into too much detail, let us look at the “ultracivilized” life in the Japanese aristocratic and imperial courts. Life in this setting was characterized by: 1) Strict codes of polite behavior 2) Constant scrutiny from peers and superiors 3) Rampant gossip 4) Well-mannered behavior 5) An obsession with beauty (in both humans and nature) Outside of nature and humans, this beauty could be found in poetry, of which the upper classes of Japan were obsessed.