July 31st, 2003 as a powerpoint file

advertisement

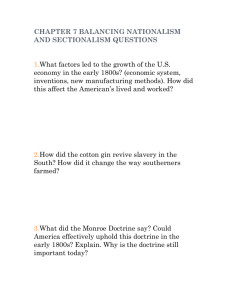

Today’s Lecture • A comment about your Third Assignment and final Paper • Preliminary comments on the Philosophy of Mind • Gilbert Ryle A comment about your Third Assignment and final Paper • I’m going to take the long weekend to grade your Third Assignments. • I am giving you a bonus day of grace to get your final Paper in to me. • Three things to note about this proposal: • (1) It means that IF you get your paper to me, or the assignment drop box, by 4:00 p.m. on August 11th, THEN you will not receive any late penalties for your paper. • (2) This extra day of grace only applies to your Paper. • (3) Technically, this does not change the due date for the paper (which remains August 8th). Third in-class quiz • Do remember that due to my oversight in not giving a third in-class quiz, and what I imagine would have been your stellar performance in answering whatever question I would have asked, each of you have received an automatic ‘2 out of 2’ for that ‘quiz that wasn’t’. Churchlands interview • Any lingering thoughts on the Churchlands? Preliminary comments on the Philosophy of Mind: Dualism • In Substance Dualism, mental states are substantially different than brain or neuronal states. The mind, under this account, is not physical or material. • In Property Dualism, certain non-physical mental properties (e.g. consciousness) emerge from the proper functioning of our brains (see FP, p.391). Preliminary comments on the Philosophy of Mind: Monism (i) Methodological Behaviorism hopes to develop a science of psychology that only regards publicly observable contingencies when explaining or predicting behavior. There is no appeal to an ‘inner realm’ of private mental (conscious or unconscious) states when explaining or predicting (human or nonhuman) animal behavior (FP, p.394). (ii) Metaphysical Behaviorism seeks to understand, describe or explain human and nonhuman animal behavior in terms of physical dispositions to act (see FP, p.391). Metaphysical Behaviorists deny that there is an ‘inner’ private realm of mentality (see FP, pp.391, 394). (iii) Logical Behaviorism seeks to reduce our discourse about the mind to discourse about dispositions to act (FP, pp.39495). Preliminary comments on the Philosophy of Mind • Mind-Brain Identity Theory contends that types of mental states are nothing more than types of brain states. • Functionalism contends that an internal state of an individual counts as a type of mental state if it performs the relevant causal role, in relation to other states of the central nervous system or non-neuronal physiological processes, and is causally efficacious in contributing to the subsequent behavior of the organism that possesses it (see FP, p.391). Gilbert Ryle • Gilbert Ryle was a British analytic philosopher. • He was born in 1900 and died in 1976. • He believed that philosophy’s primary twofold task was to (1) highlight ambiguities or confusions in certain expressions about ourselves, the world or the supernatural and in so doing resolve certain philosophical difficulties that have arisen due to these ambiguities or confusions and (2) give reformed robust philosophical analyses of our ordinary concepts (that do not yield unnecessary philosophical puzzles or confusions). Gilbert Ryle • Our readings are only part of a larger project, this being the first chapter of his book The Concept of Mind, of showing the conceptual ambiguities and confusions attaching to the way philosophers, theologians, and others have used mental vocabulary (e.g. terms like belief, desire, preference and the like) (FP, p.393). • Ryle was probably a logical behaviorist (FP, p.394). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • First thing to note about this section of the chapter is that it is no longer true that Cartesian Dualism is the “official doctrine” on mind (in philosophical circles) … largely thanks to the attacks of philosophers like Ryle. • It is interesting to note, however, that is was so at the time this book was written (circa 1949) … which is not that long ago (FP, p.396). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • Cartesian Dualism proffers the following about the human mind: • (1) Every properly functioning human of a certain, to-bespecified maturity, has a dual nature - they are, or have, a body and a mind (FP, p.396). • (2) Though the mind is causally connected to the body in life, it can survive the death of the body (and without a loss of personal identity) (FP, p.396). • (3) Human bodies, being in space, are subject to the various causal regularities, or laws, of nature (FP, p.396). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (4) The biological life of humanity is a public affair (FP, p.397). • (5) The human mind, which is not located in space, is not subject to the various causal regularities, or laws, of nature (FP, p.397). • (6) The mental life of humanity is a private affair (FP, p.397). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • “A person therefore lives through two collateral histories, one consisting of what happens in and to his body, the other consisting of what happens in and to his mind” (FP, p.397). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (7) Each individual cognizer has special access to at least some of the mental episodes making up their inner (mental) life. This access yields certain knowledge of these episodes (FP, p.397). • (8) Talk of an inner (mental) and outer (physical) world must be metaphorical. This metaphor can lead to confusion, but the mind is not literally inside anything (FP, p.397). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (9) This is because the mind is in time but not space, while the body is in both time and space (FP, p.397). • (10) What is physical is material, or a “function of matter” (FP, p.397). • (11) What is mental is immaterial, consisting of consciousness or “a function of consciousness” (FP, p.397). • (12) We only directly know our own minds (and [at least some of] its content). All other minds we know indirectly (if we know of them at all) (FP, p.398). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (13) Knowledge of our own minds is immediate (FP, p.398). • (14) We also possess the ability to observe our minds at work (i.e. we have introspective access to our own minds) (FP, p.398). • (15) Our indirect knowledge of other minds (if we have knowledge of other minds at all) is predicated upon suggested analogies between our own behavior (and our immediate knowledge that such behavior arises from causally efficacious [albeit private] mental states) and the behavior of others (FP, p.398). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (16) This indirect process of getting to know other minds (if we get to know them at all) leaves open the strong possibility that anyone of us is mistaken about the mindedness of another (FP, p.399). • (17) Our use of mental vocabulary, when used to describe or explain the behavior of another, is theoretical or hypothetical. With a framework of understanding these terms that is importantly first-person, they are supposed to refer, when used correctly, to analogous private mental episodes occurring in the mind of another (FP, p.399). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • Problems for Cartesian Dualism raised in this section of Chapter One: • (1) There is no available means to explain the nature of the states which transfer data from the (immaterial) mind to the (material) body. These states are neither introspectively available or observationally available to the cognizer, philosopher, psychologist or physiologist. What’s more, they can’t be of either a material or immaterial nature. After all, they mediate the gap between matter, or the physical, and consciousness (FP, p.397). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • There have been attempts by some Substance Dualists to ‘deal with’ this problem with interactionism. • Parallelism is the view that our mental lives somehow, and rather mysteriously, run parallel to the physical world (this is almost always a view held by theists). This deals with interactionism by denying the causal connection between mind and body (i.e. this deals with interactionism by denying it exists). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • Two important versions of Parallelism are: • (i) Occasionalism and (ii) Pre-Established Harmony Theory. • (i) Occasionalism: This is the view that the events in the physical and mental worlds run parallel to each other because of the constant intervention of God to ensure that the relevant events are in perfect alignment as you ‘move’ from the mind to the body (and the greater physical environment). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (ii) Pre-Established Harmony Theory: This is the view that God has determined the course that the mental and physical worlds have taken and are going to take. The harmony between events in the physical and mental worlds was preestablished (in God’s mind before creation). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • Problems for Cartesian Dualism raised in this section of Chapter One (continued): • (2) Only we ourselves have direct and certain knowledge of our own minds, under this account. This produces two problems in itself. • (i) We know from ever growing clinical evidence of psychology and psychiatry that introspection is not a reliable means to know our own minds. This raises the possibility that no one has direct and certain knowledge of any one’s mind. Our claims of knowledge about our own minds must, then, be verified or confirmed. But how can we do this without trapping ourselves in a viciously circular process of reasoning? (FP, p.398) Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Official Doctrine • (ii) We can only have inferential arguments for the existence of other minds. Given that (a) behavior is not, by any stretch of the imagination, an infallible indicator of particular mental states, or any mental states at all, and (b) that I’m basing this inference on an analogy with only one case, namely my own, it really could be the case that I am alone. After all, the inferential argument for other minds cannot be a very strong one (FP, pp.398-99). But this seems absurd. Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Absurdity of the Official Doctrine • Ryle christens the official doctrine of Cartesian Dualism the “Ghost in the machine” (FP, p.399). • Ryle’s primary criticism of Cartesian Dualism is neither epistemological nor metaphysical. • He will contend that Cartesian Dualists make a logical mistake in talking of minds, a mistake Ryle christens a “category mistake” (FP, p.399). • “It [i.e. the Official Doctrine] represents the facts of mental life as if they belonged to one logical type or category (or range of types or categories), when they actually belong to another” (FP, p.399). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Absurdity of the Official Doctrine • “University tour” example: Imagine taking a tour of university campuses like Western, where the university campus is relatively spread out. You’re not alone, let’s suppose. As the tour finishes your companion turns to your tour guide and says, “This is all fine and good, but when are we going to see the university?” • This is a category mistake. Your tour companion is under the impression that the university buildings and the associated, and various, administrative bodies fall under a category importantly different from the category ‘university’. I.e. she is treating the university as a thing over and above the buildings and institutional bodies she has encountered, or has been ‘introduced’ to (FP, pp.399-400). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Absurdity of the Official Doctrine • “Marching division” example: Imagine you have taken a child to see a parade of the local Canadian Armed Forces. He sees the various members of the Forces march by him, and when it is all over asks “But when are we going to see the Division march by?” • This, again, is a category mistake. The child is mistakenly treating the various members of the division as one class of thing and the division itself as something over and above these armed personnel (FP, p.400). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Absurdity of the Official Doctrine • “Team spirit” example: Imagine that we are watching a cricket match together as a group. One of us is seeing the game for the first time, and so we explain the various roles played by the various team members of ‘our side’. After explaining the position of each team player, he asks “But who is responsible for the team spirit?” • This is a category mistake. ‘Team spirit’ is being treated as if it is a position over above the various positions to be taken up by a well put together team. It is thus confusing the categories of team spirit (how the team works together as a unit) and bowler or fielder (FP, p.400). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Absurdity of the Official Doctrine • Category mistakes are philosophically important, and interesting, when committed by well educated users of the relevant natural language (FP, p.400). • This, suggests Ryle, is what has happened with those who hold the Official Doctrine of the Ghost in the Machine. • Through long experience with the differing semantic contexts in which we talk of our bodies or talk of our minds, philosophers (and others) have mistakenly concluded that each context indicates that the subjects of discourse are importantly different things, though on the same level of being (FP, p.401). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Origin of the Category-Mistake • Ryle explains the origins of this category mistake in the following ways (note he does not yet claim to have proved that the Cartesian Dualist has committed a category mistake [see FP, p.401]): • (1) Descartes was both a person of science and religion. As his religious sensibilities ran counter to the contemporary understanding of the physical world, he refused to go any further than the human body when defending the mechanistic view of the world (FP, p.401). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Origin of the Category-Mistake • (2) Differences in ontology where needed to justify this refusal, and so Descartes (and others) committed himself (and themselves) to a metaphysical category mistake that became known as substance dualism (FP, p.401). But this generated its own problems, like interactionism, the problem of the freedom of the will and the problem of other minds. These problems only emerge, Ryle suggests, if you suppose mind and body to be importantly two different categories of thing (FP, pp.401-02). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Origin of the Category-Mistake • The common test for a category mistake is seeing if two (or more) terms can be legitimately conjoined in the same sentence. • So claiming “I bought a left-hand glove and a right handglove” is perfectly fine, but I make an important category mistake if I claim that “I bought a left-hand glove and a right hand-glove and a pair of gloves”. • Being a pair of gloves is not some-thing over and above being a matched set of a left-hand and right-hand glove (FP, p.403). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Origin of the Category-Mistake • Cartesian Dualists, according to Ryle, make this kind of mistake when talking, in the same sentence, of simultaneously occurring mental processes and physical processes as if they are importantly different kinds of things, or categories of things, but at the same level of existence. • I.e. the fundamental mistake is thinking that, when we talk in this way, we are talking of two kinds of things that are on the same ontic level [or level of being] (FP, p.403). Chp.1 of The Concept of Mind: The Origin of the Category-Mistake • An interesting consequence of Ryle’s position is the claim that both Materialism and Idealism are mistaken metaphysical theses. • A reduction of the mental to the physical, or a reduction of the physical to the mental, only makes sense if they exist in the same way, or are competing classes of things at the same level of being ... which, according to Ryle, they are not (FP, p.403).