Ryle: Descartes` Myth - Villanova University

advertisement

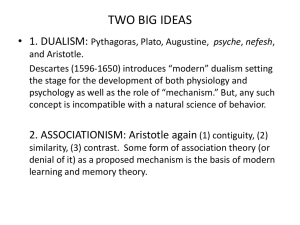

Philosophy 4610 Ryle: “Descartes’ Myth” 1. The ‘official doctrine’. So far, we have considered Descartes’ ‘first-person’ approach to the mind, an approach that starts with one’s own mind and with our own, first-person reflection on it. But starting this week, we’ll consider ‘third-person approaches’ that start in the objective world, not with the individual. There are good reasons for going for third-person approaches in their own right, and thinking aout the diference can show us some problems with first-person approaches like Descartes’. Ryle’s view, in particular, is a linguistic approach. It starts by asking about the meaning of the language that we use to describe mental and physical life, and suggests that if we pay attention to the way this language works, we can understand the mind better. In particular, we can see that the Cartesian, dualistic picture is false, and is based on a large-scale misunderstanding of the language of the mental. Ryle’s main goal is to dispute the “official doctrine” of Cartesian dualism. He will begin by characterizing it, and then he will point out some big problems with it. Ryle describes the official doctrine as follows: “With the doubtful exceptions of idiots and infants in arms every human being has both a body and a mind. Some would prefer to say that every human being is both a body and a mind. His body and his mind are ordinarily harnessed together, but after the death of the body his mind may continue to exist and function.” (p. 32) This is the view that Ryle will also call the view of the “ghost in the machine”. He will also call it the “double life theory.” It holds that our lives are divided between two separate streams or strata, two separate “biographies” – mind and body – that go along in parallel but are not descriptions of the same thing. Ryle goes on to describe the implications of the standard view, in a way that is very reminiscent of Descartes. According to the official doctrine, “human bodies are in space and are subject to … mechanical laws.” But minds are not in space. The events that happen with the body are public: that means that anyone can see them or know them. But the events that happen to the mind are private: only I can know them for sure. I know what is happening in my own mind by a special ability, that is something like visual seeing but also different: this ability is called “introspection” or inward-looking. Again, the life of the mind is characterized as the “inner” life and the life of the body as the “outer” life. What happens in the “inner realm” of the mind is known immediately and directly. And we can be immediately certain of what happens in the inner realm, with a certainty greater than anything we can know of the outer. 2. Problems with the ‘official doctrine’. This official view, dualism, is very familiar to us, and it has become part of our everyday language and ordinary thinking through the influence of metaphors and turns of phrase. But there are various problems with it. One big problem is the one we have already discussed: the problem of causality, of how mind causes things to happen in the body and how body causes things to happen in the mind. Ryle thinks that is already sufficient to show us that the official view is probably false. But there is also another problem, concerning our ways of knowing about other minds. Suppose I hope that I will pass my test. According to the official view, I can know my own mental state immediately and with certainty. But suppose you hope that you will pass your test. According to the official view, this is a private mental state in your mind, and I have no way of knowing it directly. I can observe your behavior; perhaps I see you pacing back and forth, and hear you saying again and again ‘I hope I will pass the test!’. But for the dualist, all of this is just behavior: I still can’t know for sure what is going on in your mind. In a very real sense, I can never know what anyone else is thinking, feeling, or sensing. All I get are signs, which may or may not correspond to anything: “The verbs, nouns, and adjectives, with which in ordinary life we describe the wits, characters and higher-grade performances of the people with whom we have to do, are required to be construed as signifying special episodes in their secret histories, or else as signifying tendencies for such episodes to occur. When someone is described as knowing, believing, or guessing something, as hoping, dreading, intending or shirking something, as designing this or being amused at that, these verbs are supposed to denote the occurrence of specific modifications in his (to us) occult stream of consciousness.” (p. 34) On the official doctrine, the mental lives of others are in themselves hidden to me, hidden as if behind a veil. The things people do or say can, at best, be signs of these things. In fact, if dualism is true, it is impossible for me even to know that anyone – besides myself – actually has a mind at all. Because all that shows up to me is the behavior of their bodies, they could always be faking it, or just carrying out actions mechanically. “Yet the explanation given presupposed that one person could in principle never recognize the difference between the rational and irrational utterances issuing from other bodies, since he could never get access to the postulated immaterial causes of some of the utterances. Save for the doubtful exception of himself, he could never tell the difference between a man and a robot.” (p. 37) If dualism is correct, then it is at least possible that everyone else, besides myself, actually has no mind at all: that everyone else is a robot, with no mind or conscious life at all. There is no way for me to exclude this, since all I have knowledge of is the “public” side of everyone else’s life. 3. The Official Doctrine is a category-mistake. According to Ryle, the official view is a mistake. But he also wants to show how it arises, and how it has come to be so influential. According to Ryle, this particular category-mistake comes from misunderstanding the way that we talk about ourselves and understand other people. “My destructive purpose is to show that a family of radical category-mistakes is the source of the double-life theory. The representation of a person as a ghost mysteriously 2 ensconced in a machine derives from this argument. Because, as is true, a person’s thinking, feeling and purposive doing cannot be descried solely in the idioms of physics, chemistry and physiology, therefore they must be described in counterpart idioms. As the human body is a complex organized unit, so the human mind must be another complex organized unit, though one made of a different sort of stuff and with a different sort of structure.” (p. 35) According to Ryle, Descartes and his contemporaries already knew how to understand bodies in general, and the human body in particular, as mechanical systems made of matter, governed by physical laws. They saw the language of physics and chemistry could be used to describe a great deal of what goes on in the world. But they also saw that the language of physics and chemistry alone could not describe people’s beliefs, hopes, intentions, motivations, etc. So they thought that the mind must be another kind of stuff, in addition to the body and connected to it causally. But this is a mistake. It is like the mistake Ryle describes of a student who goes to the university, and sees all the individual buildings, stadiums, and libraries (etc.) and then asks where the university itself is. The student is making a logical mistake: he doesn’t see that the building, stadiums, etc. and the university itself are not items on the same level. Rather, the university is made up of these buildings, stadiums, etc. In the same way, the person who thinks that we are made up of both a mind and a body is making a confusion of levels. He is describing two things that are on different logical levels as if they were on the same level, and mutually interacted. For Ryle, when we describe someone’s “mind” or mental life, we are really just describing things that happen to them or that they do – things that happen in the physical world, and not in some other, ghostly world of the mind. This does not mean that we are really speaking the language of physics when we talk about other people’s minds or behavior. But it does mean that we are not describing some separate, shadowy realm behind the scenes. This has the effect of solving the problem of “other minds” that troubles the dualist. For on Ryle’s view, to say that you are hoping you passed your test is not to say something about your mysterious and occult mental states, but just something about the way you are actually behaving or likely to behave. There is now no special problem about how I know this: I know it in just the same way I know anything about things in the world, by perception and observation. Of course, my observation can be wrong: but this is generally true with observations. Instead of construing the phrase “he hopes he passed his test” as referring to a mysterious, obscure mental object, Ryle construes it as referring to the ordinary ways people behave: the behavioral criteria for hoping, wanting, etc. Construed this way, our knowledge of “other minds” is no more mysterious than our knowledge of anything else we know about the world outside ourselves. It is just part of our ordinary ways of understanding and operating with the world, a world that includes, beyond ourselves, other people as well. 3