Bonds at Your Stage of Life

advertisement

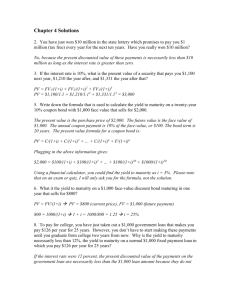

Understanding Bonds By Nina Røhr Rimmer, Associate Professor, MSc. Econ A bond is a debt security, similar to an ”I Owe You document” (IOU). When you purchase a bond, you are lending money to a government, municipality, corporation, federal agency or other entity known as the issuer. In return for the loan, the issuer promises to pay you a specified rate of interest during the life of the bond and to repay the face value of the bond (the principal) when it “matures,” or comes due. Among the types of bonds you can choose from are: Government securities, municipal bonds, corporate bonds, mortgage and asset-backed securities, federal agency securities and foreign government bonds. Key Bond Investment Considerations There are a number of key variables to look at when investing in bonds: the bond’s maturity, redemption features, credit quality, interest rate, price, yield and tax status. Together, these factors help determine the value of your bond investment and the degree to which it matches your financial objectives. Interest Rate Bonds pay interest that can be fixed, floating or payable at maturity. Most debt securities carry an interest rate that stays fixed until maturity and is a percentage of the face (principal) amount. Typically, investors receive interest payments semi-annually. For example, a DKK 1,000 bond with an 8% interest rate will pay investors DKK 80 a year, in payments of DKK 40 every six months. When the bond matures, investors receive the full face amount of the bond—DKK 1,000. But some sellers and buyers of debt securities prefer having an interest rate that is adjustable, and more closely tracks prevailing market rates. The interest rate on a floating—rate bond is reset periodically in line with changes in a base interest—rate index, such as the rate on Treasury bills. Some bonds have no periodic interest payments. Instead, the investor receives one payment—at maturity—that is equal to the purchase price (principal) plus the total interest earned, compounded semi-annually at the (original) interest rate. Known as zero—coupon bonds, they are sold at a substantial discount from their face amount. For example, a bond with a face amount of DKK 20,000 maturing in 20 years might be purchased for about DKK 5,050. At the end of the 20 years, the investor will receive DKK 20,000. The difference between DKK 20,000 and DKK 5,050 represents the interest, based on an interest rate of 7%, which compounds automatically until the bond matures. If the bond is taxable, the interest is taxed as it accrues, even though it is not paid to the investor before maturity or redemption. Maturity A bond’s maturity refers to the specific future date on which the investor’s principal will be repaid. Bond maturities generally range from one day up to 30 years or more. In some cases, bonds have 1 been issued for terms of up to 100 years. Especially the new Covered Bonds often have long maturity as they are backed by real estate. Maturity ranges are often categorized as follows: Short—term notes: maturities of up to five years; Intermediate notes/bonds: maturities of five to 10 years; Long—term bonds: maturities of 10 or more years. Redemption Features While the maturity period is a good guide as to how long the bond will be outstanding, certain bonds have structures that can substantially change the expected life of the investment. Call Provisions For example, some bonds have redemption, or “call” provisions that allow or require the issuer to repay the investors’ principal at a specified date before maturity. Bonds are commonly “called” when prevailing interest rates have dropped significantly since the time the bonds were issued. Before you buy a bond, always ask if there is a call provision and, if there is, be sure to obtain the “yield to call” as well as the “yield to maturity.” Bonds with a redemption provision usually have a higher annual return to compensate for the risk that the bonds might be called early. Put Provision Conversely, some bonds have “puts,” which allow the investor the option of requiring the issuer to repurchase the bonds at specified times prior to maturity. Investors typically exercise this option when they need cash for some purpose or when interest rates have risen since the bonds were issued. They can then reinvest the proceeds at a higher interest rate. Principal Payments and Average Life In addition, mortgage—backed securities are typically priced and traded on the basis of their “average life” rather than their stated maturity. When mortgage rates declines, home-owners often prepay mortgages, which may result in an earlier—than—expected return of principal to an investor. This may reduce the average life of the investment. If mortgage rates rise, the reverse may be true—homeowners will be slow to prepay and investors may find their principal committed longer than expected. Your choice of maturity will depend on when you want or need the principal repaid and the kind of investment you are seeking within your risk tolerance. Some individuals might choose short—term bonds for their comparative stability and safety, although their investment returns will typically be lower than would be the case with long—term securities. Alternatively, investors seeking greater overall returns might be more interested in long—term securities despite the fact that their value is more vulnerable to interest rate fluctuations and other market risks as well as credit risk. 2 Credit Quality Bond choices range from the highest credit quality Treasury securities, which are backed by the full faith and credit of the government, to bonds that are below investment—grade and considered speculative. Since a bond may not be redeemed, or reach maturity, for years—even decades—credit quality is another important consideration when you’re evaluating a fixed—income investment. When a bond is issued, the issuer is responsible for providing details as to its financial soundness and creditworthiness. This information is contained in a document known as an offering document, prospectus or official statement, which will be provided to you by your investment advisor. But how can you know whether the company or government entity whose bond you’re buying will be able to make its regularly scheduled interest payments in five, 10, 20 or 30 years from the day you invest? Rating agencies assign ratings to many bonds when they are issued and monitor developments during the bond’s lifetime. Securities firms and banks also maintain research staffs which monitor the ability and willingness of the various companies, governments and other issuers to make their interest and principal payments when due. Your investment advisor or the issuer of the bond can supply you with current research on the issuer and on the characteristics of the specific bond you are considering. Credit Ratings In the United States, major rating agencies include Moody’s Investors Service, Standard & Poor’s Corporation and Fitch Ratings. Each of the agencies assigns its ratings based on in—depth analysis of the issuer’s financial condition and management, economic and debt characteristics, and the specific revenue sources securing the bond. The highest ratings are AAA (S&P and Fitch Ratings) and Aaa (Moody’s). Bonds rated in the BBB category or higher are considered investment—grade; securities with ratings in the BB category and below are considered “high yield,” or below investment—grade. While experience has shown that a diversified portfolio of high—yield bonds will, over the long run, have only a modest risk of default, it is extremely important to understand that, for any single bond, the high interest rate that generally accompanies a lower rating is a signal or warning of higher risk. How can you find out if the credit factors affecting your bond investment have changed? Usually, rating agencies will signal they are considering a rating change by placing the security on CreditWatch (S&P), Under Review (Moody’s) or on Rating Watch (Fitch Ratings). The rating agencies make their ratings available to the public through their ratings information desks. In addition, their published reports and ratings are available in many local libraries. Many also provide online ratings information that can be accessed through the Internet. 3 Bond Credit Quality Ratings Rating agencies Credit Risk Investment grade Highest quality High quality (very strong) Upper medium grade (strong) Medium grade Not investment grade Lower medium grade (somewhat speculative) Low grade (speculative) Poor quality (may default) Most speculative No interest being paid or bankruptcy petition filed In default Standard & Poor’s** Moody’s* Fitch Ratings** Aaa Aa A Baa AAA AA A BBB AAA AA A BBB Ba B Caa Ca BB B CCC CC BB B CCC CC C D C C D D * The ratings from Aa to Ca by Moody’s may be modified by the addition of a 1, 2 or 3 to show relative standing within the category. ** The ratings from AA to CC by Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings may be modified by the addition of a plus or minus sign to show relative standing within the category. Bond Insurance Credit quality can also be enhanced by bond insurance. Specialized insurance firms serving the fixed—income market guarantees the timely payment of principal and interest on bonds they have insured. In the United States, major bond insurers include MBIA, AMBAC, FGIC and FSA. (See glossary for list.) Most bond insurers have at least one triple—A rating from a nationally recognized rating agency attesting to their financial soundness, although some bond insurers bear lower credit ratings. In either event, insured bonds, in turn receive the same rating based on the insurer’s capital and claims—paying resources. While the focus of their underwriting activities has historically been in municipal bonds, bond insurers also provide guarantees in the mortgage and asset—backed securities markets and are moving into other types of securities as well. An investor may also buy bond insurance on a bond purchased in the secondary market. 4 Price The price you pay for a bond is based on a whole host of variables, including interest rates, supply and demand, credit quality, maturity and tax status. Newly issued bonds normally sell at or close to their face value. Bonds traded in the secondary market, however, fluctuate in price in response to changing interest rates. When the price of a bond increases above its face value, it is said to be selling at a premium. When a bond sells below face value, it is said to be selling at a discount. Yield Yield is the return you actually earn on the bond—based on the price you paid and the interest payment you receive. There are basically two types of bond yields you should be aware of: current yield and yield to maturity or yield to call. Current yield is the annual return on the dollar amount paid for the bond and is derived by dividing the bond’s interest payment by its purchase price. If you bought at DKK 1,000 and the interest rate is 8% (DKK 80), the current yield is 8% (DKK 80 ÷ DKK 1,000). If you bought at DKK 900 and the interest rate is 8% (DKK 80), the current yield is 8.89% (DKK 80 ÷ DKK 900). Yield to maturity and yield to call, which are considered more meaningful, tell you the total return you will receive by holding the bond until it matures or is called. It also enables you to compare bonds with different maturities and coupons. Yield to maturity equals all the interest you receive from the time you purchase the bond until maturity (including interest on interest at the original purchasing yield), plus any gain (if you purchased the bond below its par, or face, value) or loss (if you purchased it above its par value). Yield to call is calculated the same way as yield to maturity, but assumes that a bond will be called and that the investor will receive face value back at the call date. You should ask your investment advisor for the yield to maturity or yield to call on any bond you are considering purchasing. Buying a bond based only on current yield may not be sufficient, since it may not represent the bond’s real value to your portfolio. Market Fluctuations - The Link between Price and Yield From the time a bond is originally issued until the day it matures, its price in the marketplace will fluctuate according to changes in market conditions or credit quality. The constant fluctuation in price is true of individual bonds—and true of the entire bond market—with every change in the level of interest rates typically having an immediate, and predictable, effect on the prices of bonds. When prevailing interest rates rise, prices of outstanding bonds fall to bring the yield of older bonds into line with higher—interest new issues. When prevailing interest rates fall, prices of outstanding bonds rise, until the yield of older bonds is low enough to match the lower interest rate on new issues. Because of these fluctuations, you should be aware that the value of a bond will likely be higher or lower than its original face value if you sell it before it matures. 5 Market Fluctuations - The Link between Interest Rates and Maturity Changes in interest rates don’t affect all bonds equally. The longer it takes for a bond to mature, the greater the risk that prices will fluctuate along the way and that the fluctuations will be greater—and the more the investors will expect to be compensated for taking the extra risk. There is a direct link between maturity and yield. It can best be seen by drawing a line between the yields available on like securities of different maturities, from shortest to longest. Such a line is called a yield curve. A normal yield curve would show a fairly steep rise in yields between short— and intermediate— term issues and a less pronounced rise between intermediate— and long—term issues. That is as it should be, since the longer the investor’s money is at risk, the more the investor should expect to earn. If the yield curve is said to be “steep,” it means the yields on short—term securities are relatively low when compared to long—term issues. This means you can obtain significantly increased bond income (yield) by buying a longer maturity than you can with a short one, and you may wish to modify your choice of bond accordingly. On the other hand, if the yield curve is “flat,” it means the difference between short— and long—term rates is relatively small. This means that the reward for extending maturities is relatively small, and many investors will choose to stay in the short end of the maturity range. When yields on short—term issues are higher than those on longer—term issues, the yield curve is said to be “inverted.” This suggests that investors expect interest rates to decline. An inverted yield curve is sometimes considered to be a harbinger of recession. The Interest Rate—Inflation Connection As an investor, you need to know how bond market prices are directly linked to economic cycles and concerns about inflation. You may have wondered why press reports say the bond market fell after the government released positive economic news about job growth or housing starts. As a general rule, the bond market, and the overall economy, benefit from steady, sustainable growth rates. Moderate economic growth also benefits the financial strength of the government, municipal and corporate issuers whose bonds you may hold, making them a stronger credit. But steep rises in economic growth can lead to inflation, which raises the costs of goods and services for everyone, leads to higher interest rates and erodes a bond’s value. Ultimately, persistent and rapid economic growth will lead to rising interest rates, either through actions taken by the 6 Federal Reserve to slow the expansion, or through market forces acting in anticipation of interest rate moves. Since rising interest rates push bond prices down, the bond market tends to react negatively to reports about strong economic growth. Duration of the Bonds The term duration has a special meaning in the context of bonds. It is a measurement of how long, in years, it takes for the price of a bond to be repaid by its internal cash flows. It is an important measure for investors to consider, as bonds with higher durations carry more risk and have higher price volatility than bonds with lower durations. Factors Affecting Duration It is important to note, however, that duration changes as the coupons are paid to the bondholder. As the bondholder receives a coupon payment, the amount of the cash flow is no longer on the time line, which means it is no longer counted as a future cash flow that goes towards repaying the bondholder. Our model of the fulcrum demonstrates this: as the first coupon payment is removed from the red lever and paid to the bondholder, the lever is no longer in balance because the coupon payment is no longer counted as a future cash flow. The fulcrum must now move to the right in order to balance the lever again: Duration increases immediately on the day a coupon is paid, but throughout the life of the bond, the duration is continually decreasing as time to the bond's maturity decreases. The movement of time is represented above as the shortening of the red lever. Notice how the first diagram had five payment periods and the above diagram has only four. This shortening of the time line, however, 7 occurs gradually, and as it does, duration continually decreases. So, in summary, duration is decreasing as time moves closer to maturity, but duration also increases momentarily on the day a coupon is paid and removed from the series of future cash flows - all this occurs until duration, eventually converges with the bond's maturity. The same is true for a zero-coupon bond Duration: Other factors Besides the movement of time and the payment of coupons, there are other factors that affect a bond's duration: the coupon rate and its yield. Bonds with high coupon rates and, in turn, high yields will tend to have lower durations than bonds that pay low coupon rates or offer low yields. This makes empirical sense, because when a bond pays a higher coupon rate or has a high yield, the holder of the security receives repayment for the security at a faster rate. The diagram below summarizes how duration changes with coupon rate and yield. If you are interested in further advanced information about calculating Duration, you can find inspiration below: Table of Contents 1) Advanced Bond Concepts: Introduction 2) Advanced Bond Concepts: Bond Type Specifics 3) Advanced Bond Concepts: Bond Pricing 4) Advanced Bond Concepts: Yield and Bond Price 5) Advanced Bond Concepts: Term Structure of Interest Rates 6) Advanced Bond Concepts: Duration 7) Advanced Bond Concepts: Convexity 8) Advanced Bond Concepts: Formula Cheat Sheet 9) Advanced Bond Concepts: Conclusion Tax Issues Some bonds offer special tax advantages. Do you want income that is taxable or income that is tax-exempt? The answer depends on your income tax bracket and the difference between what can be earned from taxable versus tax-exempt securities not only presently but also throughout the period until your bonds mature. The decision about whether to invest in a taxable bond or a tax-exempt bond can also depend on whether you will be holding the securities in an account that is already tax-preferred or tax-deferred, such as a pension account. 8 In Denmark, as a general rule, interest payments are fully taxed in your Personal Income (as Net Capital Income with current marginal rates between 33% - 60%), whereas capital gains on the bonds are tax exempt. Both interest and capital gains on bonds in Pension Schemes are currently taxed at 15%. Risks of Bond Investing Virtually all investments have some degree of risk. When investing in bonds, it’s important to remember that an investment’s return is linked to its risk. Higher return equals higher risk. Conversely, relatively safe investments offer relatively lower returns. The bond market is no exception to this rule. Bonds in general are considered less risky than stocks for several reasons: Bonds carry the promise of their issuer to return the face value of the security to the holder at maturity; stocks have no such promise from their issuer. Most bonds pay investors a fixed rate of interest income that is also backed by a promise from the issuer. Stocks sometimes pay dividends, but their issuer has no obligation to make these payments to shareholders. Historically the bond market has been less vulnerable to price swings or volatility than the stock market. The average returns from bond investments have also been historically lower, if more stable, than average stock market returns. While generally considered safer and more stable than stocks, bonds have certain risks – the most significant are: Interest rate risk: when interest rates rise, bond prices fall. If you need money and have to sell your bond before maturity in a higher rate environment, you will probably get less than you paid for it. Interest rate risk declines as the maturity date gets closer. Credit risk: if the issuer runs into financial difficulty or declares bankruptcy, it could default on its obligation to pay the bondholders. Liquidity risk: if the bond issuer’s credit rating falls or prevailing interest rates are much higher than the coupon rate, it may be hard for an investor who wants to sell before maturity to find a buyer. Bonds are generally more liquid during the initial period after issuance as that is when the largest volume of trading in that bond generally occurs. Call risk or reinvestment risk: If a bond is callable, the issuer can redeem it prior to maturity, on defined dates for defined prices. Bonds are usually called when interest rates are falling, leaving the investor to reinvest the proceeds at lower rates. 9 It’s all relative to “Risk free” Treasury Yields Bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government (or other government bonds such as Danish Government bonds) and therefore considered to have no credit risk. The market for U.S. Treasury securities is also the most liquid in the world, meaning there are always investors willing to buy. U.S. Treasury yields will almost always be lower than other bonds with comparable maturities because they have the fewest risks. Relative yields—which may be discussed in terms of “spread” or difference in yield between a given bond and a “riskless” U.S. Treasury security with comparable maturity—vary with the type of bond, maturity date, the issuer and the economic cycle. Callable bonds are riskier than non-callable bonds, for example, and therefore offer a higher yield, particularly if the call date is soon and interest rates have declined since the bond was issued, making it more likely to be called. Short-term bonds with maturities of three years or less will usually have lower yields than longterm bonds with maturities of 10 years or more, which are more susceptible to interest rate risk. All bonds have more risk when interest rates are rising, but those with the lowest coupons stand to lose the most value. Additional Risks of investing in all types of bonds: Duration risk The modified duration of a bond is a measure of its price sensitivity to interest rates movements, based on the average time to maturity of its interest and principal cash flows. Duration enables investor to more easily compare bonds with different maturities and coupon rates by creating a simple rule: with every percentage change in interest rates, the bond’s value will decline by its modified duration, stated as a percentage. For example, an investment with a modified duration of 5 years will rise 5% in value for every 1% decline in interest rates and fall 5% in value for every 1% increase in interest rates. Bond portfolio managers increase average duration when they expect rates to decline, to get the most benefit, and decrease average duration when they expect rates to rise, so minimize the negative impact. If rates move in a direction contrary to their expectations, they lose. Reinvestment risk When interest rates are declining, investors have to reinvest their interest income and any return of principal, whether scheduled or unscheduled, at lower prevailing rates. Inflation risk Inflation causes tomorrow’s dollar to be worth less than today’s; in other words, it reduces the purchasing power of a bond investor’s future interest payments and principal, collectively known as “cash flows.” Inflation also leads to higher interest rates, which in turn leads to lower bond prices. Inflation-indexed securities (in US - Treasury Inflation Protection Securities (TIPS) in Denmark Indexed Bonds) are structured to remove inflation risk. 10 Market risk The risk that the bond market as a whole would decline, bringing the value of individual securities down with it regardless of their fundamental characteristics. Selection risk The risk that an investor chooses a security that underperforms the market for reasons that cannot be anticipated. Timing risk The risk that an investment performs poorly after its purchase or better after its sale. Risk that you paid too much for the transaction The risk that the costs and fees associated with an investment are excessive and detract too much from an investor’s return. Liquidity risk The risk that investors may have difficulty finding a buyer when they want to sell and may be forced to sell at a significant discount to market value. Liquidity risk is greater for thinly traded securities such as lower-rated bonds, bonds that were part of a small issue, bonds that have recently had their credit rating downgraded or bonds sold by an infrequent issuer. Bonds are generally the most liquid during the period right after issuance when the typical bond has the highest trading volume. How to Invest There are several ways to invest in bonds. You can buy individual bonds, bond funds or unit investment trusts. Individual Bonds There is an enormous variety of individual bonds to choose from. Your investment advisor can help you find a bond that matches your investment needs and expectations. Most individual bonds are bought and sold in the over-the-counter (OTC) market, although some corporate bonds are also listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The OTC market comprises hundreds of securities firms and banks that trade bonds by phone or electronically. Some are dealers that keep an inventory of bonds and buy and sell these bonds for their own account; others act as agent and buy from or sell to other dealers in response to specific requests on behalf of customers. If you’re interested in purchasing a new bond issue, your investment advisor will provide you with the security’s offering statement, or prospectus—the official document that explains the bond’s terms and features, as well as risks that investors should know about before investing. You can also buy and sell bonds which have already been issued. This is known as the secondary market. Many dealers keep inventories of a variety of outstanding (i.e., previously issued) bonds. Bonds sold in the over-the-counter market are usually sold in DKK 5,000 denominations. In the secondary market for outstanding bonds, prices are quoted as if the bond were traded in DKK 100 increments. Thus, a bond quoted at 98 refers to a bond that is priced at DKK 98 per DKK 100 of face value, or at a 2% discount. 11 Bond prices normally include a mark-up, which constitutes the dealer’s costs and profit. If a broker or dealer has to seek out a specific bond that is not in their inventory for a customer, a commission may be added to compensate for the costs and efforts of serving the customer’s special needs. Each firm establishes its own prices within regulatory guidelines, which may vary depending upon the size of the transaction, the type of bond you are purchasing and the amount of service the firm provides. Bond Funds Every bond has certain characteristics: A definite maturity date when the bond issuer promises to repay the bondholder who owns the security at the time. A promise to pay taxable or tax-exempt interest at a stated “coupon” rate in defined intervals over the life of a bond. A yield, or return on investment, which is a function of the bond’s coupon rate and the price the investor pays, which may be more or less than the bond’s face value depending on a variety of factors. A credit rating indicates the likelihood that the issuer will be able to repay its debt. Bond funds offer investors another way to invest in the bond markets. Bond funds, like stock funds, offer professional selection and management of a portfolio of securities. They allow an investor to diversify risks across a broad range of issues and offer a number of other conveniences, such as the option of having interest payments either reinvested or distributed periodically. Because a fund is actively managed, with bonds being added to and eliminated from the portfolio in response to market conditions and investor demand, bond funds do not have a specified maturity date. With “open—end” funds, you are able to buy or sell your share in the fund whenever you choose. But because the market value of bonds fluctuates, as previously described, a fund’s net asset value will change from day to day, reflecting the cumulative value of the bonds in the portfolio. As a result, when you sell, the value of your investment—as reported in most daily newspapers—may be higher or lower, depending upon how the fund has performed since you purchased your share. “Closed—end” bond funds have a specific number of shares that are listed and traded on a stock exchange. Because the fund managers are less concerned about having to meet investor redemptions on any given day, their strategies can be more aggressive. Most funds charge annual management fees averaging 1%, while some also impose initial sales charges (some up to 5%) or fees for selling shares. Because the annual management fees will lower returns, investors need to be aware of the total costs when calculating their overall expected returns. 12 Money Market Funds Money market funds, as the name implies, refer to pooled investments in short—term, highly liquid securities. These securities include U.S. Treasuries, municipal bonds, certificates of deposit issued by major commercial banks, and commercial paper issued by established corporations. Generally, these funds consist of securities and other instruments having maturities of three months or less. Money market funds also offer convenient liquidity, since most allow investors to withdraw their money at any time. However, money market funds are not insured or guaranteed by the U.S. government and there can be no assurance that the fund will be able to maintain a stable net asset value of DKK 1.00 per share. Bond Unit Investment Trusts Bond unit investment trusts offer a fixed portfolio of investments in government, municipal, mortgage—backed or corporate bonds, which are professionally selected and remain constant throughout the life of the trust. The benefit of a unit trust is that you know exactly how much you will earn while you’re invested in it, because the composition of the portfolio remains stable. Also, since the unit trust is not an actively managed pool of assets, there is usually no management fee, but investors do pay a sales charge, plus a small annual fee to cover supervision, evaluation expenses and trustee fees. As an investor, you can earn interest income during the life of the trust and recover your principal as securities within the trust are redeemed. The trust typically ends when the last investment matures. Diversifying Risk by Building a Portfolio Bond investors can diversify risk by purchasing bonds from different issuers with different maturities. As mentioned, the cost of buying a bond includes a commission or a “mark-up” on the price, depending on whether you are buying from a firm acting as an agent who is getting the bond from someone else, or as principal, meaning the firm owns the bond it is selling. Executing an effective diversification strategy requires a significant minimum investment to start. While there is no absolute requirement, a rule of thumb says it often takes at least DKK 10,000 or more to build a fully diversified bond portfolio. As you build your investment portfolio of fixed—income securities, there are various techniques you and your investment advisor can use to help you match your investment goals with your risk tolerance. Diversification No matter what your investment objective, it makes good sense to diversify your portfolio. Diversification can provide some protection for your portfolio, so if one sector or asset class is in the midst of a downturn, the rising value of another class of assets may help offset the negative impact. For example, suppose your portfolio held a variety of high—yield and investment—grade bonds. You chose the high—yield securities for their greater returns. The investment—grade bonds probably generate somewhat lower yields, but their ability to weather economic downturns should 13 offset potential credit—quality concerns which could affect the high—yield securities in the portfolio. Similarly, you might want to balance corporate issues with U.S. Treasury, municipal or mortgage—backed issues offered by government—sponsored agencies. Laddering Another diversification strategy is to purchase securities of various maturities. When you buy bonds with a range of maturities, a technique called laddering; you are reducing your portfolio’s sensitivity to interest rate risk. If, for example, you invested only in short—term securities, the kind least sensitive to changing interest rate risk, you would have a high degree of stability, but you might be giving up yield. Conversely, investing only in long—term securities may result in greater returns, but their prices will be more volatile, exposing you to losses should you have to sell before maturity. Building a laddered portfolio involves buying an assortment of bonds with maturities distributed over time. For example, you might invest equal amounts in securities maturing in two, four, six, eight and 10 years. In two years, when the first bonds mature, you would reinvest the money in a 10—year maturity, maintaining the ladder. Your return would be higher than if you bought only short—term issues. Your risk would be less than if you bought only long—term issues. You would be better protected against interest rate changes than with bonds of one maturity. If interest rates fell, you’d have to reinvest the securities maturing in two years at a lower rate, but you’d have the above—market return from the other issues. If rates rose, your total portfolio would pay a below—market return, but you could start correcting that in two years or less when your shortest issue matured. Barbell This strategy also involves investing in securities of more than one maturity to limit your risk against fluctuating prices. But instead of dividing your money in a series of bonds distributed over time, as with a laddered portfolio, you’d concentrate your holdings in bonds with maturities at both ends of the spectrum, long— and short—term—for example, bills or notes maturing in six months or a year, and 20— or 30—year bonds. Bond Swap Investors use bond swaps to realize a variety of benefits. A swap, the simultaneous sale of one security and the purchase of another, may be done to change maturities, upgrade the credit quality of the portfolio, increase current income or achieve a number of other objectives. The most common swap is done to achieve tax savings. Anyone owning bonds selling below their purchase price and having capital gains or other income which could be partially, or fully, offset by a tax loss can benefit from a tax swap. In a two—step process, the investor would sell a bond that is worth less than what he paid for it and would simultaneously purchase a similar bond at approximately the same price. By swapping the securities, the investor has converted the paper loss to an actual loss 14 which can be used to offset capital gains and up to DKK 3,000 of ordinary income each year on a joint return. Bond Funds: Convenient, Affordable way to invest in a Diversified Portfolio of Bonds? Bond funds offer a convenient and affordable way to invest in a diversified portfolio of bonds, but a bond fund investment can differ from a bond investment in ways that are important to understand. When you buy a bond fund, you buy shares in a portfolio of bonds that is created or managed to pursue a specific investment objective such as current income, current tax-exempt income, total return, or to match the performance of a market index. The portfolio might invest in a particular type of bond (government, municipal, mortgage or high-yield) or a particular maturity range (shortterm: three years or less; intermediate term: three to 10 years; or long-term: usually 10 years or longer). Types of bond funds Bond mutual funds can be actively managed or indexed, open-end, closed end or exchange traded funds. Actively managed bond funds, as their names suggest, have managers who buy and sell bonds in pursuit of their investment objective. They sometimes sell bonds at a profit, creating a capital gain, or at a loss if they need cash to pay shareholders who want to sell their shares. Index bond funds are not actively managed but constructed to match the composition of a given bond index, such as the Lehman 10-year Bond Index. When the index changes, the portfolio changes automatically. Sponsors of open-end bond funds (usually a mutual fund company) offer new shares and redeem existing shares continuously, requiring their managers to invest cash coming into the fund and liquidate positions when they need cash to meet redemptions. Investors in open end funds have the choice to collect their interest income and capital gains or reinvest them automatically in new funds shares. Closed-end bond funds have a fixed number of shares that trade on exchanges similar to stocks at a price that may be above or below net asset value depending on supply and demand. Closed-end bond funds can be indexed or actively managed. To buy or sell shares in a closed end fund, you have to go through a broker and pay a commission. Exchange traded funds (ETFs) represent shares in a “basket” of bonds that mirrors an index, but the number of shares is not fixed. ETFs trade on an exchange, with shares bought and sold through brokers who charge commissions. Unit investment trusts are a portfolio of bonds held in a trust that sells a fixed number of shares. On the trusts’ maturity date, the portfolio is liquidated and the proceeds returned to unit holders on a pro rata basis. UITs are usually created by brokerage firms that maintain a limited secondary market for the units. Unit holders who want to sell before maturity may have to accept less than they paid. 15 Bonds at Your Stage of Life It’s a common misconception that bonds are only for very old, very rich or very conservative investors or very young (savings bonds for kids). In fact, bonds are an important component of a strategically-balanced portfolio at every stage of any investor’s life. Bonds can: provide investment stability to help buffer against the volatility of the stock market pay a steady stream of income, sometimes tax-free income, which can help with living expenses provide high rates of return to grow your capital play different roles at different points in your life to help you achieve your financial goals The key to a well-balanced portfolio is asset allocation and diversification. Asset allocation is spreading your money across a good mix of equity investments (stocks), debt investments (bonds) and cash instruments to maximize the return of the entire portfolio. Diversification is investing in various vehicles across asset classes to reduce the risk that any one investment may pose to your overall portfolio. Unfortunately there is no hard and fast rule, or formula, about how much to invest and where to invest. Your investment strategy will change over time, reflecting your investment horizon (how much time there is between now and when you want to access the money you are investing) and your risk tolerance (how much risk you are willing to take in exchange for a possible higher rate of return.) So whether you are just starting out in your career or you are already enjoying retirement, or if you are somewhere in between, bonds should be a part of your investment portfolio. Let’s look at the role bonds can play at each stage of your life. Starting Out: Investing in Your 20s and 30s Investment Goal at this Stage Maximize Capital (your most likely primary financial goal at this point) Investment Horizon Very Long (30 - 40+ years) (how long until you need to access your money) Risk Tolerance High (how much risk you feel comfortable taking) At the beginning of your career you may have a hard time imagining life 15, 30 or 40 years from now. Chances are that you are more concerned about paying bills and saving money toward bigticket items such as a car, a wedding, a house or having a baby. Since you have a longer horizon for investing (the amount of time between now and when you want/need to access your money), you are in a better position to consider investing in higher-yield, higher-risk instruments. There are higher-risk bonds that carry high coupons (interest rates). You may be interested in assuming that risk to potentially make significant interest on your investment. 16 Keep in mind, however, that even at this early stage of the investment game, you want to aim for a well-blended portfolio to balance risk and market volatility. While your higher-yield investments can appear more exciting (because of their potential to earn more interest), it’s important to round out your portfolio with some strategically chosen lower- and medium-risk investments as well, including bonds. Depending on your circumstances bonds can help you: Grow capital through high-yield returns There are high-risk/high-yield bonds that may be of interest to you as you look to grow financially. Remember that when you invest in higherrisk instruments you face a greater potential for loss due to interest rate risk and credit risk. Carefully research each bond offering and know a bond issue’s conditions and terms (including its’ rating, call features and whether or not it is insured) prior to investing. A financial advisor may be able to help you. Click here to learn more about “Selecting and Working with a Financial Professional.” Preserve your savings for a big future purchase If you are saving money for a large future purchase—a car, a wedding, a house—you might consider investing that savings in a low-risk bond with a maturity date that matches the date you will need the money. For example, new issue U.S. Treasury bills, notes and bonds are available directly from the Federal Reserve in three-month, six-month, and two-year and three-year maturities in DKK 1,000 increments starting at DKK 1,000. You can also buy outstanding Treasury or corporate bonds with maturities timed to your needs in the secondary market through a bank or a broker. Prices and yields will vary. Diversify your employer-sponsored retirement plan If your 401(k) or other employersponsored retirement plan offers a variety of mutual funds, you might want to allocate some portion of your assets toward bond funds to diversify your holdings and spread your risk. Because the stock and bond markets do not often move in the same direction, bond investments can stabilize and even enhance your overall returns. You might look into highyield and long-term bond funds if you want to take more risk for the possibility of higher returns. Supplement your income Maybe you’ve received an inheritance or other large sum of money. Investing it in bonds can help you preserve the principal for the future while generating interest income that you can spend now. Depending on how much you have to invest, you might want to consider constructing a bond portfolio yourself with the help of an advisor, or investing in another type of bond investment such as a unit trust or bond fund. Develop discipline with dollar-cost averaging One of the common myths about investing is that you have to have a lot of money to do it. That’s a good reason to consider dollar-cost averaging. If you can only invest a small amount at a time, or if you are uncomfortable investing large chunks of money at once, dollar cost averaging can be a way to invest in bonds automatically on a regular schedule. First, consider working with a financial advisor to determine what types of bond investments are appropriate for your portfolio. Next, select a regularly scheduled date to have a pre-determined amount of money automatically withdrawn from an account of your choice and have it deposited into your brokerage account to purchase (or earmark toward purchase) the bonds you have chosen. Making small deposits over time will add up to consistent investments which can reap significant 17 dividends over the long term. Think you don’t have enough money to invest? Consider the dollar-cost averaging approach to purchase bonds for your portfolio. In the Middle: Investing in Your 30s and 40s Investment Goal Capital Growth (your most likely primary financial goal for your principal at this point) Investment Horizon Long (20—30+ years) (how long until you need to access your money) Risk Tolerance Moderate (how much risk you feel comfortable taking) The middle years—mid-30s to late 40s—are crucial to accumulating and wisely investing toward your retirement and long-term financial goals. Even if you didn’t, or couldn’t, start saving and investing earlier you need to begin making up for lost time. If you’re between 35 and 55, you are probably earning enough to live more comfortably now than when you were younger, but are increasingly concerned about funding your retirement and paying for your children’s education. While you still have time in your investment horizon to be able to recover from a market downturn, you don’t want to have your portfolio so heavily loaded in highrisk investments that you could lose the bulk of your money if the stock market or your individual stocks decline significantly. Because your investment horizon is somewhat shorter than when you were first starting out in your twenties, you should rebalance your portfolio to make sure that you have allocated your assets appropriately. Financial advisers usually recommend that at this point in your investment life it would be prudent to shift your investments to focus more on medium-risk and low-risk instruments, while still maintaining a healthy, but smaller, percentage of investments in higher-risk instruments. Remember that the key is spreading, or allocating, your assets across investments of varying degrees of risk to blend the risk you’re taking and to maximize your interest-earning potential. Consult a financial advisor for investment recommendations and assistance. Bonds should represent a larger portion of your asset allocation than they did when you were younger. Bonds provide a stable backbone and more predictable income generation than equities. Following are some bond strategies to consider at this stage in your investment life. As always, it’s a good idea to consult a financial advisor before making any investment decisions. Zero Coupon bonds for specific goals Zero coupon bonds are sold at a steep discount from their face value. When the bond matures, the face value reflects both the principal and the interest accumulated. Buying a zero coupon now with a maturity that coincides with the year your child starts college or the year you would like to retire can be a cost-effective way to increase the likelihood that you will have the money you need when you need it. Zero coupon bonds work best in a qualified, tax-deferred retirement or college savings account because the interest is taxable when it is credited to the bond, even though you can’t spend it until maturity. 18 Tax-advantaged bond investing If you’re in a high tax bracket, tax-advantaged municipal bonds issued by state and city governments may be more attractive than corporate bonds that pay taxable interest income. Interest paid on most U.S. government securities is exempt from state and local income tax, which can be important if you live in a high-tax state. Municipal bonds pay interest that is exempt from federal income tax, and, depending on the issuer, possibly from state and city income tax as well. To see how much you would have to earn on a fully taxable investment to match the return of a tax-exempt investment you’re considering, use the Taxable Equivalent Yield calculator. You can earn tax-exempt interest on bonds and bond funds that qualify. In most cases, you don’t want to put this kind of investment in a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account, however, so you don’t waste the tax exemption feature. Increasing your allocation to bonds If you have not yet started investing a portion of your assets in bonds, now may be a good time to start. If you are willing to take a little more risk for the possibility of higher returns, consider high-yield or longer-term bonds or bond funds. Nearing Retirement: Investing in Your 50s and 60s Investment Goal Conserve capital (your most likely primary financial goal at this point) Investment Horizon Moderate (5 - 15 years) (how long until you will need to access your money) Risk Tolerance Low (how much risk you feel comfortable taking) Hopefully by this point the hard work and discipline of saving and investing is creating a solid portfolio that enables you to look forward to financial freedom in your retirement. As retirement approaches, your investment horizon shrinks. In other words, the closer you are to retirement, the less chance you want to take that you could lose a sizable portion of your investments. You want to more aggressively protect your assets from the stock market’s volatility. Many advisors suggest that people at this point begin increasing the bond portion of their portfolio to 50% or more to lower their overall investment risk. Some issues to consider when evaluating bonds for your portfolio: Bonds or Bond Funds? The bond markets offer investors many choices and sectors, each with a slightly different risk and return profile. As with all investments, diversification is important in your bond investments too. Because many kinds of bonds can only be bought in minimum increments of DKK 5,000, creating a bond portfolio that includes different issuers, market sectors, maturities and credit qualities can require a significant amount of assets. Bond funds, unit trusts or exchange-traded funds may be a better choice for more convenient and affordable diversification, although they don’t offer the comfort of a single bond’s promise that your principal will be returned on the maturity date. Tax-advantaged bond investing If you’re in a high tax bracket, tax-advantaged bonds issued by federal, state and city governments may be more attractive than corporate bonds paying taxable interest income. Interest paid on most U.S. government securities is exempt 19 from state and local income tax, which can be important if you live in a high-tax state. Municipal bonds pay interest that is exempt from federal income tax, and, depending on the issuer, possibly from state and city income tax as well. To see how much you would have to earn on a fully taxable investment to match the return of a tax-exempt investment you’re considering, use the Taxable Equivalent Yield calculator. You can earn tax-exempt interest on bonds and bond funds that qualify. In most cases, you don’t want to put this kind of investment in a tax-deferred retirement or college savings account, however, as that would be wasting the tax exemption. Managing interest rate risk The rule of thumb is that when interest rates rise, bond prices fall and vice versa. If you buy a bond with a 5% coupon and interest rates on the same maturity rise to 6%, not only will your bond be worth less if you want to sell it before maturity, but you will also be missing the opportunity to earn higher interest. One way to manage this risk is with laddering. Creating a portfolio of bonds with maturities staggered over one, three, five and ten years, for example, helps you do well in any interest rate environment. When rates are rising, you will have short-term bonds maturing that allow you to reinvest the principal at higher rates. When rates are falling, you will still have the longerterm bonds paying higher coupons. Retirement: Investing in Your 60s Investment Goal Preserve Capital (your most likely primary financial goal at this point) Investment Horizon Short (Immediate Access to Funds) (how long until you need to access your cash) Risk Tolerance Very Low (how much risk you feel comfortable taking) During retirement your main investment focus is ensuring your financial security. Most financial advisors say you'll need about 70 percent of your pre-retirement earnings to comfortably maintain your pre-retirement standard of living. If you have average earnings, your Social Security retirement benefits will replace only about 40 percent. Your investments and your employer’s plan, if you have one, will have to make up the rest. Bonds can generate an important source of retirement income while preserving your principal. When thinking about bonds, think about: Maximizing your lifetime income The right kind of bond investments for you will depend on your life expectancy, your tax bracket, and the amount of risk you can afford to take. High yield and longer-term bonds may have higher coupons, but they also can put your principal at risk if you need to sell the bond before it matures and the issuer’s credit quality has declined or interest rates have risen. Consider a balanced bond fund where you can supplement your regular income with a percentage of your earnings while still maintaining enough capital in the fund to outpace inflation. If you’re in a higher tax bracket you may benefit from the federal (as well as possibly state and local) tax-exempt interest from municipal bonds. 20 Guarding against inflation Retirees living on a “fixed income” can lose purchasing power if inflation increases. To help guard against this risk, you might consider including Treasury Inflation Protection Securities (TIPS) or Treasury Inflation Indexed Securities in your investment portfolio. TIPS have a fixed coupon rate, but their principal amount is adjusted every six months according to changes in the Consumer Price Index. As a result, the amount of your income that should stay represents equivalent purchasing power. At maturity, you get the higher of the original face value or the inflation-adjusted amount. Another way to guard against inflation is to keep a small percentage of your portfolio invested in stocks for their greater growth potential. Spend from taxable income first Remember that if you’re in a position where your cash assets won’t cover ongoing or one-time expenses you will want to dip into your taxable investment accounts first. Taking money from a tax-advantaged retirement plan, such as a 401(k) or IRA, can have tax implications and early withdrawal penalties. Keep an eye on CD maturity and bond maturity rates in your portfolio and consider cashing those out and retaining a portion before rolling the sum into another vehicle when they mature. 21 Bond Basics Glossary Accrued interest Interest deemed to be earned on a security but not yet paid to the investor. Ask price Price being sought for the security by the seller. Basis point One—hundredth of 1 percent. for example 50 basis points = ½ per cent. Yield differences among fixed—income securities are stated in basis points. Bid The price at which a buyer offers to purchase a security. Bond insurers and reinsurers A partial list of bond insurers includes American Municipal Bond Assurance Corp. (AMBAC), ACA Financial Guaranty, AXA Re Finance, Financial Guaranty Insurance Co. (FGIC), Financial Security Assurance (FSA), Municipal Bond Insurance Association (MBIA), Radian Asset Assurance and XL Capital Assurance. Callable bonds Bonds which are redeemable by the issuer prior to the maturity date at a specified price at or above par. Cap The highest interest rate that can be paid on a floating—rate security. Collar Upper and lower limits (cap and floor, respectively) on the interest rate of a floating—rate security. Coupon This part of a bearer bond denotes the amount of interest due, and on what date and where payment will be made. Bearer coupons are presented to the issuer’s designated paying agent for collection. With registered bonds, physical coupons don’t exist. (See “Registered bond.”) The payment is mailed directly to the registered holder. Note that while bearer bonds are no longer issued in the United States and, hence, physical coupons are increasingly scarce, 22 dealers and investors often still refer to the stated interest rate on a registered or book—entry bond as the “coupon.”. Current yield The ratio of interest to the actual market price of the bond, stated as a percentage. For example, a bond with a current market price of DKK 1,000 that pays DKK 80 per year in interest would have a current yield of 8%. Default Failure to pay principal or interest when they are due. Defaults can also occur for failure to meet non—payment obligations, such as reporting requirements, or when a material problem occurs for the issuer, such as a bankruptcy. Duration The weighted maturity of a fixed—income investment’s cash flows, used in the estimation of the price sensitivity of fixed—income securities for a given change in interest rates. Face amount Par value (principal or maturity value) of a security appearing on the face of the instrument. Floating—rate bond A bond for which the interest rate is adjusted periodically according to a predetermined formula, usually linked to an index. High—yield bond Bonds issued by lower—rated corporations, sovereign countries and other entities rated Ba or BB or below and offering a higher yield than more creditworthy securities; sometimes known as junk bonds. Issuer An entity which issues and is obligated to pay principal and interest on a debt security. Interest Compensation paid or to be paid for the use of money. Interest is generally expressed as a percentage rate. 23 Junk bond A debt obligation with a rating of Ba or BB or lower, generally paying interest above the return on more highly rated bonds; sometimes known as high—yield bonds. Leverage The use of borrowed money to increase investing power. LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) The rate banks charge each other for short—term loans. LIBOR is frequently used as the base for resetting rates on floating—rate securities. Liquidity or Marketability A measure of the relative ease and speed with which a security can be purchased or sold in the secondary market at a price that is reasonably related to its actual market value. Maturity The date when the principal amount of a security is payable. Mortgage pass—through A security representing a direct interest in a pool of mortgage loans. The pass—through issuer or servicer collects payments on the loans in the pool and “passes through” the principal and interest to the security holders on a pro rata basis. Non—callable bond A bond that cannot be called for redemption by the issuer before its specified maturity date. Offer The price at which a seller will sell a security. Par value The principal amount of a bond or note due at maturity. Premium The amount by which the price of a security exceeds its principal amount. 24 Prepayment The unscheduled partial or complete payment of the principal amount outstanding on a mortgage or other debt before it is due. Prepayment risk The risk that falling interest rates will lead to heavy prepayments of mortgage or other loans—forcing the investor to reinvest at lower prevailing rates. Primary market The market for new issues. Principal The face amount of a bond, payable at maturity. Ratings Designations used by credit rating agencies to give relative indications of credit quality. Reinvestment risk The risk that interest income or principal repayments will have to be reinvested at lower rates in a declining rate environment. Secondary market Market for issues previously offered or sold. Settlement date The date for the delivery of securities and payment of funds. Swap Simply, the sale of a block of bonds and the purchase of another block of similar market value. Swaps may be made to achieve many goals, including establishing a tax loss, upgrading credit quality, extending or shortening maturity, etc. Trade date The date when the purchase or sale of a bond is transacted. 25 Unit investment trust Investment fund created with a fixed portfolio of investments that never changes over the life of the trust. As investments within the trust are paid off, they provide a steady, periodic flow of income to investors. Yield The annual percentage rate of return earned on a security. Yield is a function of a security’s purchase price and coupon interest rate. Yield curve A line tracing relative yields on a type of security over a spectrum of maturities ranging from three months to 30 years. Yield to call A yield on a security calculated by assuming that interest payments will be paid until the call date, when the security will be redeemed at the call price. Yield to maturity A yield based on the assumption that the security will remain outstanding to maturity. It represents the total of coupon payments until maturity, plus interest on interest, and whatever gain or loss is realized from the security at maturity. Zero—coupon bond A bond on which no periodic interest payments are made. The investor receives one payment—which includes principal and interest—at redemption (call or maturity). (See “Discount note.”). Sources, Litterature etc. Skat.dk Danskebank.dk Realkreditdanmark.dk Nykredit.dk Investopedia.com 26