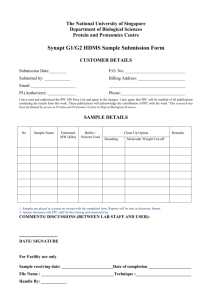

Report Template

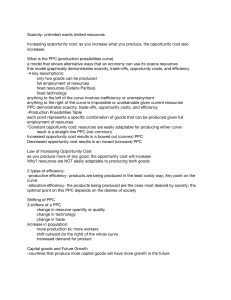

advertisement