Hypotheses for Epidemiology FAQ

advertisement

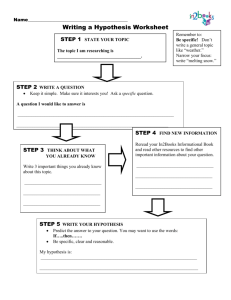

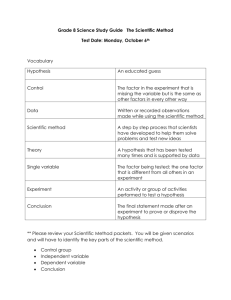

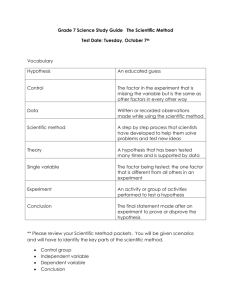

Hypothesis Formation in Epidemiology FAQ These FAQs will assist you as you complete this task about forming good, testable hypotheses. What is a hypothesis? A hypothesis is a tentative answer to a well-formed question. Modern scientists commonly follow a five-step process (known as the scientific method) when pursuing a problem or developing a theory. (1) They make an observation. This might be some phenomenon the scientist ran into by accident, but more often it will be something he or she observed while studying a problem. (2) They ask questions about the observation(s). (3) They form a hypothesis—a tentative answer to a question. (4) They make predictions based on the hypothesis. (5) They test the predictions. What is a scientific hypothesis? If a hypothesis can’t give rise to predictions that could be tested and found false, it is not a scientific hypothesis. In principle, any scientific hypothesis is subject to testing and falsification. If no evidence could conceivably disprove it, a hypothesis is not scientific. Interestingly, hypotheses cannot be proven to be correct. They can continually be challenged by some new test or piece of evidence proving them to be false. How do I create a hypothesis? A hypothesis begins with a question—the hypothesis is a tentative answer or explanation that addresses the question. Suppose you are looking for something in the dark, using a flashlight. Your flashlight goes out. Your question is almost certainly “Why did the flashlight go out?” Stop and think for a moment… can you create one or two hypotheses (answers to your question)? One reasonable hypothesis would be: The batteries are dead. Another reasonable hypothesis would be: The bulb has burned out. Generate hypotheses by thinking of them as answers to questions. Remember, though: A hypothesis is a scientific hypothesis only if it could be tested. What is an alternative hypothesis? The “alternative” hypothesis is a statement that you believe to be true. For example, let’s say you have a theory and you want to test it. First, you come up with the alternative hypothesis, which is your theory: “An employer who has a screening process is more likely to hire a quality candidate than an employer who just hires the first person that asks him/her for a job.” This hypothesis states the direction (e.g., more likely, less likely) and tells the reader what you believe to be true. What is a null hypothesis? While it may seem counterintuitive, the unstated goal of any study is not to prove the alternative hypothesis, but it is actually to try to disprove the null hypothesis (as mentioned previously, hypotheses cannot be proven to be correct). In epidemiology, when a hypothesis is stated as the null, it says there is no difference between group 1 and group 2. At the end of a study, you find that the null is either not true and there is an explanation for the difference between the two groups or you find that the null is true and there’s no difference between the two groups. Here are examples of null hypotheses: 1. If you want to test whether more boys or girls at Lakeview High prefer to drink Coke versus Pepsi, the null hypothesis would be, “There is no difference between the percentage of girls and the percentage of boys who drink Coke instead of Pepsi at Lakeview High.” 2. If you want to test whether students who listen to music while doing homework have lower or higher GPAs, the null hypothesis would be, “There is no difference in GPA between those high school students who usually listen to music while doing homework and those who rarely listen to music while doing homework.” In epidemiology, what makes a hypothesis “good” (or testable)? There are two important keys to a good, testable hypothesis. It must be simple and specific. Simple – you should always test one variable at a time, not multiple variables. If you try to include multiple variables in your hypothesis, you won’t ever be able to determine the direct association. Example - If your alternative hypothesis states that smoking and alcohol consumption both lead to heart disease, how will you determine who falls into the “exposed” group (the group exposed to the thing that leads to heart disease)? People who smoke? People who drink? Or only people who smoke and drink? It’s better to have two hypotheses, and to test each separately. The first hypothesis could examine the relationship between alcohol and heart disease and the second could address the relationship between smoking and heart disease. Specific – your hypothesis should be as specific as you can make it. Whenever possible, you should include details that indicate exactly what you are looking for in your study. For your alternative hypothesis, this includes the direction of the association (e.g., people who smoke are more likely to get lung cancer; people who exercise regularly are less likely to get heart disease). Example - Let’s say you have a theory that people who drink coffee have stomach problems. There are some additional questions that need to be answered so your hypothesis is easier to test: How much coffee? What are the steps in forming a null hypothesis? Compared to whom? What kind of stomach problems? 1. Think of the question you want to research. 2. Turn the question into a statement that says what you think to be true or what you hope to find out (alternative hypothesis). 3. Make sure the hypothesis is both simple and specific. 4. Reframe the hypothesis and make it “null” by stating that there is no difference between group 1 and group 2.