Word document

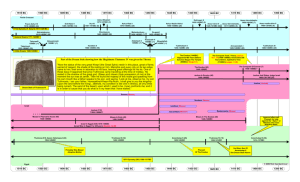

advertisement

NOTES ON THE FIRST READINGS FOR THE FIFTEENTH WEEK OF ORDINARY TIME (Cycle 1) (if a festal day falls on any of these days, the readings of the feast are used instead) We continue from the book of Genesis into the book of Exodus, the second of the five books of the Pentateuch (‘five scrolls’). Our Bible gives this book its title from the Greek (‘coming out’ [of Egypt]), though the actual coming out is not the only event described in it. Exodus also deals with the giving of the Law to Moses on Sinai, and the presence of God with his people in the “tabernacle” or dwelling. The Jewish Bible calls this book by the first words of verse 1: “these are the names …” The whole Pentateuch has been subject to an editing process, culminating in the work of the Priestly author after the exile to Babylon; this process was described in the introduction to the book of Genesis. The hands of various author-editors will be seen, as in Genesis, throughout this book. The hero of Exodus is Moses, the model for God’s other servants in the Bible, including the prophets (Isaiah and Jeremiah) and of course Jesus himself. Moses’ role is that of mediator, to bring the wavering and often sinful people into a right relationship with God. Exodus consists of two main ‘panels’, which overlap: the rescue of the Hebrews from slavery (chapters 1 to 15:21) and the twelve stages of their journey to Sinai (chapter 12:37 to 40:38), the first three of which take place within Egypt itself, hence the overlap. Monday: Exodus 1: 8-14, 22. Joseph is dead and a new king, the Pharaoh, fears that the numerous Hebrews may rebel against him and desert. He decides to quell them, firstly with forced labour. When that fails, he determines to kill all the male children. The city of Rameses, which the Hebrews have to build, could be identified with the ‘Raamses’, a great city on the old course of the Nile, built under Ramses II (12901224BC), which had to be abandoned when the Nile’s course silted up and changed. Tuesday: Exodus 2: 1-15. The birth of Moses. There are many traditions of a ‘hidden child’, including from within Egypt itself. Following Pharaoh’s orders, Moses on birth is literally ‘thrown into the Nile’, but not to perish. The involvement of Pharaoh’s daughter means that the child Moses is actually brought up at the court of the one who wished to be rid of him and all his kind. The name Moses is explained by reference to Hebrew ‘draw out’ (of water), though in fact in Egyptian tradition it means the more prosaic ‘born of’. When he grows up, Moses’ Hebrew origins show as he defends his own people, and he is obliged to flee for his life to Midian, beyond the Jordan, where he will marry. Wednesday: Exodus 3: 1-6, 9-12. Moses at the Burning Bush, where God reveals his presence. In the original, there is a play on words between ‘bush’ and ‘Sinai’. As with other Biblical leaders (e.g. Jeremiah) Moses shows himself reluctant to accept God’s commission. In order to be able to worship the true God in freedom, the people must leave Egypt, which is seen as the land of slavery to a false god. Moses asks for a sign, but unusually no prior sign is given. Moses is told only that his future worship of God on Sinai will be a sign that God’s will has indeed been accomplished. Thursday: Exodus 3: 13-20. Moses asks for God’s name. One of the authors of the Pentateuch tells us (Genesis 4:26) that the people called God ‘Yahweh’ (our Bibles translate as “The Lord”); Yahweh may possibly be translated as ‘He who causes to be …’ The name which God gives himself here is a first-person version, which may mean ‘I am who I am’ or ‘I will be who I will be’. It expresses the total freedom of God. In a way God does not give a direct answer for Moses; the name represents the person, whereas God’s essential personhood cannot be comprehended by any human being. God says that the elders of the Hebrews will accept Moses, that they will ask Pharaoh for leave to go to the wilderness, that he will refuse, and that God will then display his power. Friday: Exodus 11:10 – 12:14. Egypt now suffers the ten plagues at God’s hand. We omit all but the tenth, the death of the Egyptian firstborn. At this point in the narrative, the final editor of the book, the Priestly writer, has inserted an account of the institution of the feasts of the Passover and Unleavened Bread, which became associated with the Exodus. Originally, the Passover and Unleavened Bread were separate feasts. Passover began as a celebration by primitive herdsmen moving their beasts from the winter pastures to the higher summer pastures, and wishing to placate the deity by offering an animal in sacrifice. Unleavened Bread was a farming festival marking the beginning of the new season with the removal of all the ‘old’ leaven of the previous year. Not only are the two feasts now linked together, but they are both made dependent on the Exodus. The blood of the Passover sacrifice serves to indicate the houses of the Hebrews, which are to be spared by the destroying angel. The unleavened bread is all that the Hebrews can take in their hasty flight from Egypt (12:34). By their nature, the two feasts marked the New Year. Hence it is the first month. The Jewish understanding of ‘memorial’ (and this is something which has passed into Christianity) allows succeeding generations to participate in the liberating event by their own ‘commemoration’ of it, something which is not to be seen only in the ‘weak’ sense of a looking back into history. Saturday: Exodus 12: 37-42. The first stage of the Exodus journey begins, taking the Israelites some 25 miles S.E. to Succoth on the way to what is properly the ‘Sea of Reeds’, to us the Red Sea. With typical Biblical exaggeration of figures to stress the grandeur of God’s design, the size of the Israelite army on the march is given in gigantic terms. The author says that this move to Succoth marked the first step in the liberation of Israel from their 430 years of slavery in Egypt. He reaches this figure by reference to the promises God gave to Abram in Genesis 15. Each generation of patriarchs is taken to be 100 years. God has promised: “They shall come back home in the fourth generation”.