Dick Sweeney

advertisement

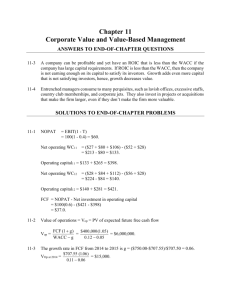

Dick Sweeney Notes on Valuing the Project/Company as a Whole For valuing the project/company as a whole, we use the Free Cash Flow (FCF) approach in this course. That is, we use the WACC approach to valuing a levered firm. This approach is based on MM Proposition II with corporate taxes. Below are some notes on applying this approach. The notes are designed to accompany Copeland, Tom, Tim Koller and Jack Murrin, Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Corporations, 2000. These notes are adapted with kind permission from a paper that Allan Eberhart originally prepared. A firm's free cash flow is defined as: Free Cash Flow = Gross Cash Flow - Gross Investment In turn, Gross Cash Flow = + Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) Taxes on EBIT Change in Deferred Taxes = + Net Operating Profit Less Adjusted Taxes (NOPLAT) Depreciation and other non-cash expenses (e.g., amortization and depletion) = Gross Cash Flow and Gross Investment = + + + Increase in Operating Working Capital Capital Expenditures Investment in Goodwill Increase in Net Other Assets (this can be a catch-all category) = Gross Investment This gives Free Cash Flow as Free Cash Flow = Gross Cash Flow - Gross Investment By adding Non-operating Cash Flow, Total After-Tax Cash Flow = Free Cash Flow + Non-operating Cash Flow Note: Because FCF depends on changes in certain variables, you clearly cannot calculate FCF for the first year for which you have financial information on the firm. Explanations 1 Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT): This is often called "operating income" on the firm's income statement. Be sure to remove any nonoperating income, if this is included: Examples of nonoperating income (losses) are gains (losses) from the sale of assets; accounting changes, etc. Taxes on EBIT: These are the taxes the firm would pay if it had no debt or excess marketable securities (note: ask whether the firm has excess marketable securities: Vick does not, but in later 1 The Copeland et al. book suggests calculating the firm’s financial flow as a check on your calculation of total after-tax cash flows. The advantage of the financial flow approach is that it highlights how the FCF is divided among the shareholders and the debtholders. The firm's financial flow is defined as: Financial Flow Financial Flow = + + + + Change in Excess Marketable Securities After-tax Interest Income Decrease in Debt After-tax interest expense Dividends Share repurchases = Financial Flow = Total After-tax Cash Flow 2 years Corning does). Specifically, Taxes on EBIT are defined as: Total income tax provision from income statement + Tax shield on interest expense Tax on the company’s interest income Tax on nonoperating income ______________________________ = Taxes on EBIT Change in Deferred Taxes The total income tax provision from the firm's reported income statement generally is not equal to the firm's actual tax payment (e.g., because the firm uses straight line depreciation for its reported earnings and MACRS for its earnings reported to the IRS). An increase in deferred taxes means the firm has paid fewer taxes than it reported (and vice versa). This will be listed on the liability side of the firm's balance sheet. If it is also listed on the asset side, then subtract this amount from the liability amount and look at the change in this difference. (Note: Firms are now required to report cash taxes paid and so you can put cash taxes in directly; to be consistent with the definition in the Valuation book, however, you can just use this indirect method.) Net Operating Profit Less Adjusted Taxes (NOPLAT): This is the firm's after-tax profits, that is, after adjusting the taxes to a cash basis. Depreciation and other non-cash expenses: Depreciation is the major noncash expense you need to worry about adding back to cash flow. More generally, for our purposes, we can add back in depreciation, depletion and amortization. Gross Cash Flow: This is the total after-tax cash flow produced by the firm. It is the amount the firm has available for maintenance and growth investment without relying on additional capital. Change in (operating) Working Capital: This is the amount the firm invests in working capital over the year. Hence, it is the change in (current assets - current liabilities). Because this is operating working capital, non-operating assets and interest-bearing liabilities are excluded (e.g., short-term debt should not be included; short-term debt includes notes payable and current portion of long-term debt). Note: You should exclude non-operating cash from the operating working capital definition; however, for our purposes, you are welcome to assume non-operating cash is zero. Capital Expenditures: This includes expenditures on new and replacement property, plant, and equipment. It can be calculated as the increase in net property, plant, and equipment on the balance sheet plus depreciation. Because depreciation and amortization are lumped together, you can include them both here. 3 Investment in Goodwill: This can be calculated as the change in intangibles plus any amortization charge. Increase in Net Other Assets: This is the increase in expenditures on all other assets. It can be calculated from the change in the balance sheet item(s). Note: In general, the change in any longterm (operating) asset category not accounted for in capital expenditures or investment in goodwill represents an investment (e.g., investment at equity) and should be put in this category. Gross Investment: This is the total investment in new capital, including working capital, capital expenditures, goodwill and other assets. Non-operating Cash Flows: These are the after-tax cash flows from items not related to operations. Examples include the proceeds from an asset sale, returns from financial investments (assuming the firm is not some type of financial institution). Change in Excess Marketable Securities Excess marketable securities are short-term cash investments that the firm holds that are in excess of its target cash balances. You can estimate this by examining other similar firms. After-tax Interest Income: This is the pre-tax interest income (on excess marketable securities) times one minus the marginal tax rate. Change in Debt : This is the net borrowing or repayment on all of the firm's debt. After-tax Interest Expense: This is the firm's pretax interest expense times 1 minus the firm's marginal tax rate. Dividends: This is the cash dividend paid to common and preferred shareholders. Share Issues/Repurchases: If stock is issued, this is a negative number; if stock is repurchased, this is a positive number. The Free Cash Flow (FCF) Approach Computing the firm's current FCF is relatively straightforward. Of course, firm value is not determined by current FCF but forecasted FCF (discounted at the WACC, plus the present value of nonoperating cash flows). Nevertheless, getting an accurate calculation of current FCF is important because forecasted FCF is computed based on the growth in each component of the current FCF. The key to understanding the FCF approach is to think back to the separation theorem. 4 This theorem says that the firm makes its investment decisions (i.e., capital budgeting decisions) first and then decides how to finance these investments. With perfect markets, MM show that the financing decision does not affect the value of the firm. With imperfections, capital structure may affect the firm's investment policy (e.g., through indirect bankruptcy costs). Capital structure may also affect the firm's WACC (as in the case of corporate taxes where interest payments are tax deductible and dividend payments are not). To keep things tractable, the FCF approach relies on the MM theory of capital structure with corporate taxes. Thus, the firm's investment policy is presumed to be independent of the capital structure. The relevance of capital structure is revealed in the WACC. Recall that at the extreme, the MM theory suggests that the firm should use 100% debt financing. Of course, this cannot be taken literally. The intelligent inference is that, at the margin, increasing the firm's debt level will decrease the WACC. Ceteris paribus, this will increase value. You should not, however, be lulled into such a simple, mechanical, increase in value; keep in mind that there can be offsetting effects (e.g., bankruptcy costs, personal taxes, agency conflicts). 5