Tagging and Graffiti Project - Ministry of Youth Development

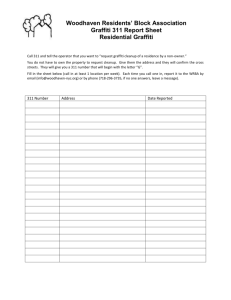

advertisement