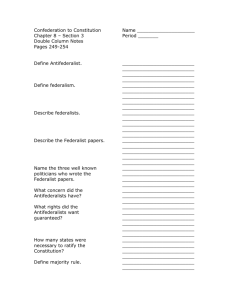

Individual Freedom and the Bill of Rights

advertisement