washingtonpost - Dr John La Puma

advertisement

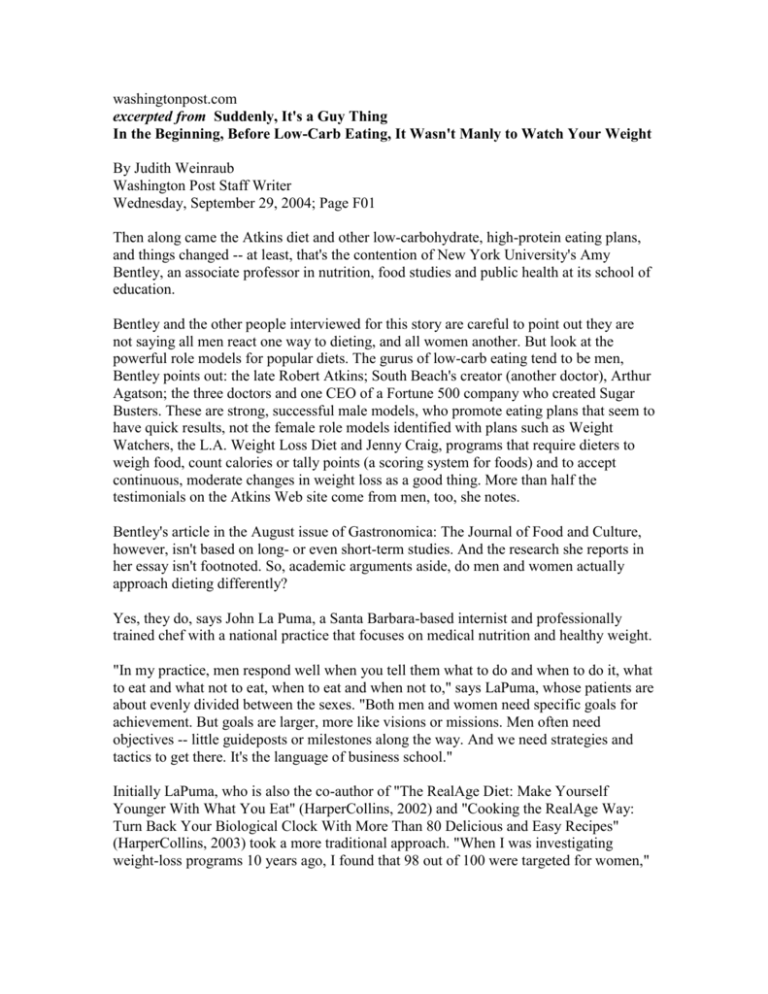

washingtonpost.com excerpted from Suddenly, It's a Guy Thing In the Beginning, Before Low-Carb Eating, It Wasn't Manly to Watch Your Weight By Judith Weinraub Washington Post Staff Writer Wednesday, September 29, 2004; Page F01 Then along came the Atkins diet and other low-carbohydrate, high-protein eating plans, and things changed -- at least, that's the contention of New York University's Amy Bentley, an associate professor in nutrition, food studies and public health at its school of education. Bentley and the other people interviewed for this story are careful to point out they are not saying all men react one way to dieting, and all women another. But look at the powerful role models for popular diets. The gurus of low-carb eating tend to be men, Bentley points out: the late Robert Atkins; South Beach's creator (another doctor), Arthur Agatson; the three doctors and one CEO of a Fortune 500 company who created Sugar Busters. These are strong, successful male models, who promote eating plans that seem to have quick results, not the female role models identified with plans such as Weight Watchers, the L.A. Weight Loss Diet and Jenny Craig, programs that require dieters to weigh food, count calories or tally points (a scoring system for foods) and to accept continuous, moderate changes in weight loss as a good thing. More than half the testimonials on the Atkins Web site come from men, too, she notes. Bentley's article in the August issue of Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture, however, isn't based on long- or even short-term studies. And the research she reports in her essay isn't footnoted. So, academic arguments aside, do men and women actually approach dieting differently? Yes, they do, says John La Puma, a Santa Barbara-based internist and professionally trained chef with a national practice that focuses on medical nutrition and healthy weight. "In my practice, men respond well when you tell them what to do and when to do it, what to eat and what not to eat, when to eat and when not to," says LaPuma, whose patients are about evenly divided between the sexes. "Both men and women need specific goals for achievement. But goals are larger, more like visions or missions. Men often need objectives -- little guideposts or milestones along the way. And we need strategies and tactics to get there. It's the language of business school." Initially LaPuma, who is also the co-author of "The RealAge Diet: Make Yourself Younger With What You Eat" (HarperCollins, 2002) and "Cooking the RealAge Way: Turn Back Your Biological Clock With More Than 80 Delicious and Easy Recipes" (HarperCollins, 2003) took a more traditional approach. "When I was investigating weight-loss programs 10 years ago, I found that 98 out of 100 were targeted for women," he says. "They were often process-oriented -- that is, they tried to make sense of the problem and reason through it the way women often do with relationships, to turn the problems over to fully understand them, and then to come out with a solution better than what they went in with. It's a thoughtful examination of the reasons for eating other than hunger, with small changes making a big difference. I started that way. . . . Three years ago, it became clear to me that it worked for some people but not for others, and the people it worked for tended to be women." What he observed about the men he treated was that generally they were goal-oriented, numbers-oriented and specific about wanting to be told exactly what to do. In general, he found that approach works for his male patients and some women -- with a caution. "The flip side is that it can seem parental," he says. "But it's not. It's more like a business partner with experience in a specific area. . . . I give them specific goals -- weight, blood pressure, cholesterol -- and I give them a specific time period to do it. . . . It's prescriptive, clear, based in science, and it gives us something to shoot for." La Puma isn't the only one to see a difference in the way men and women diet. At Weight Watchers (where the amount and kinds of food allowed have been based on a point system that is reliant on calories as well as grams of dietary fiber and fat), low-carb diets are seen as serious competition, especially for male clients. Men have never been a large part of the Weight Watchers constituency. Trying to make sense of that, the company did extensive research about "extreme dieting" -- that is low-carb and no-carb dieting -- in the United States. "We wanted to understand men, and their needs, preferences and weight issues," says Karen Miller-Kovach, the company's chief scientific officer. At Weight Watchers, for example, research has indicated that men go on diets primarily for the same reasons that women do: to feel and look better, as opposed to a concern about their health. In contrast, LaPuma finds that his patients (who tend to be CEOs, very successful people, yet they haven't been able to solve their weight problems) care mightily about potential health hazards of being overweight. "They don't want the fact they're obese or hypertense or have high cholesterol to steal from them what they've earned in life," he says. Whatever the reason for dieting, the weight problem isn't going to go away -- for women or for men. "There's too much food out there, too many choices. It's too tempting," says NYU's Bentley. "We're in desperate times." © 2004 The Washington Post Company