- World Bank

advertisement

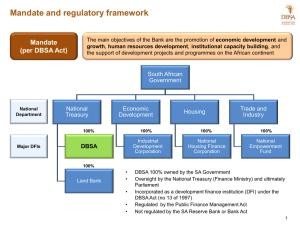

Session 3: Role of State-Owned Financial Institutions Lewis Musasike 6th Annual Financial Markets and Development Conference The Role of State-Owned Financial Institutions: Policy and Practice April 26-27, 2004 Washington, DC For more information, see: http://www.worldbank.org/wbi/banking/finsecpolicy/stateowned2004/ 1 The role of Development Finance Institutions: Lessons from southern Africa of best practices for their effective management Lewis Musasike 1 , Ted Stilwell, Moraka Makhura, Barry Jackson & Marie Kirsten2 1. Introduction In both the economies of developed and developing nations, the State has always played a central role, although dominance has changed over time in response to globalisation, privatisation and the perceived efficiencies of the private sector. The establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions was a landmark in the reshaping of the international finance system and the development finance system in particular. In subsequent years, regional economic and political groups established their own development institutions in the 1960s such as the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. Sub-regional and national development financial institutions gained prominence with the support of the Bretton Woods institution; and as more and more nations gained independence and nationhood from western nations. A number of these institutions were created for political reasons, but served to address the development challenges related to provision of basic services; the creation of jobs; the promotion of foreign exchange earnings and building better infrastructure. In most developing nations, there was no dividing line between public finance and development finance with governments often using DFIs as conduits for fiscal transfers; and in reverse using them as sources of funding budgetary deficits. The result was that over time, DFIs became a drag on the fiscus of many governments and were finally left to disappear. The demise of many DFIs at national and even sub-regional level was precipitated by structural reforms of the 1980s and 1990s (as dictated by the Bretton Woods institutions), the privatisation trends which began in the mid-1980s in developed nations, and mismanagement and corrupt practices. As the role of the state was reduced, so did the influence of state-owned enterprises, with the exception of those deemed to be of strategic importance to the well-being of the state. From an African perspective, the performance of the continent has lagged behind other regional groupings worldwide. This has led to the re-examination of the real challenges facing African countries in their quest for development, hence the birth of the New Programme for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) initiative. Politically, the transformation of the OAU to the African Union revealed the determination of Africans to promote good governance and tackle civil strife across the continent. Regional integration is a principle feature of the NEPAD strategy. The strategy argues that the prevailing economic conditions point to the need for African countries to pool their resources and enhance regional development and economic integration in order to improve international competitiveness. NEPAD underscores a break with the past – it emphasises African ness and African responsibility while recognising the need for constructive support from, 1 . Executive Manager Treasury, Development Bank of Southern Africa Contact details; DBSA, P O Box 1234, Halfway House, 1685, SOUTH AFRICA. http://www.dbsa.org 2 Policy Analysts, Policy Business Unit, DBSA. 2 and partnerships with, other regions of the world if sustained and sustainable development are to be realities for the continent. Recently, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly accepted NEPAD as the basis for all UN engagements with Africai. This resolution in effect significantly elevates the standing and credibility of the approach adopted by African leaders. It also implies that, with regard to their support for Africa, all multi- and bilateral agencies and organisations will now depart from similar principles and focus on the same overarching vision drawn from NEPAD. In the same way NEPAD’s agenda for action poses new development challenges for DFIs in Africa. This paper sets out a general perspective on development finance and DFIs, with particular reference to their role and functions in providing focused financial and development support to bolster human development and economic growth at national and regional level. The case of the Development Bank of Southern Africa, its scope and nature is reviewed in the next section. Some of its breakthroughs and challenges are highlighted to draw out lessons of best practice in the management of DFIs. The final section puts forward a set of policy conclusions. 2. Development Finance Institutions in perspective Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) are post world war two, post colonial developments, designed to provide focused financial support to national and regional development efforts and bolster economic growth (Diamond, 1957).ii. Development finance is that set of financial flows, largely of a capital nature, that involves investments in development projects or ventures, in income generating activities, public or private, that operate on the basis of commercial profitability, and full cost recovery (Hoffmann, 1998)iii. DFIs address market, political or bureaucratic imperfections and asymmetry arising from perceived or actual financial risk by delivering a structured package of support to their clients. The most classical role of DFIs is to fill the gaps in domestic fiscal and term-lending capabilities of under-developed and developing countries. They seek to address the capital market inefficiencies where private capital is unwilling or unable to bear the risk of providing capital to countries, projects or clients that are not considered creditworthy. They further seek to fill the fiscal gap between capital for pure pubic good provided by the state and commercial projects where there is cost recovery (Mistry)iv. This particular DFI role in support of development finance can be depicted as illustrated below: Fiscal transfers and grants Cost recovery 3 Cost recovery Private sector capital DFI niche Risk potential Risk Risk Cost recovery The model schematically illustrates the "gap" in the financing system. It implies that by and large pure public goods and projects that lack sufficient income generating capability do not constitute a substantial part of a DFIs loan portfolio. Special fiscal, grant and concessionary funding vehicles are required to meet many basic human needs and social services, with the DFIs and the private sector supplementing these efforts with loan funding on the basis of cost recovery from beneficiaries. The gap in the graph is illustrative of the DFI market niche. The interface areas may vary from sector to sector and client to client depending on the financial model which the DFI adopts as well as the funding sources and the DFI’s ability to access resources and concessionary finance from multilateral and bilateral agencies. The above schematic model further illustrates the potential for co-funding with the private sector and for various tripartite funding modalities. The most prominent of a DFIs package of services is thus the extension of loan finance on beneficial terms to revenue-generating enterprises and projects. This “development banking” ability of DFIs stems from their capitalisation, usually consisting of public sector equity and fiscal transfers, often augmented by loan or grant capital from private and donor sources. As governments face more budgetary constraints and development aid Development Finance is usually applied to investments in revenuegenerating enterprises and projects or ventures – public or private. declines, DFIs have been Projects financed may be; commercially profitable; or involve fullforced to become less cost recovery autonomous to the enterprise; or partial cost recovery, dependent on central with an explicit subsidy provided by government. Application is governments, and have generally confined to the initial capital outlay (and/or first cycle of had to use their financial working capital) (Kritzinger, L, World Bank 2002) strength to intermediate between the providers of capital (financial markets and international funders) and users of capital who otherwise cannot access this capital directly. By intermediating, DFIs can substantially reduce the cost of capital to borrowers by the partial transfer of a subsidy through the interest rate or the tenor (maturity and grace periods), asset and liability matching or by stipulating less onerous collateral requirements. Further, DFIs have a better understanding of developmental risk, a higher risk appetite, and a stronger risk rating, all of which they can use to benefit poorer or unrated clients. The inclusion of more commercially orientated projects in their portfolios also allows them to cross-subsidise development projects in poor areas. Recently, Public Private Partnerships (PPP’s) have materialized as important financial instruments through which DFIs can structure their “development banking” portfolios by mobilising resources in partnerships with private sector players. These products and services include equity, quasi-equity instruments, senior debt, subordinated debt and guarantees, syndication underwriting, and arranging. Through their willingness to take political and general country risks that private sector investors have less appetite for, non-financial constraints to private sector investment in what is perceived to be economically depressed areas are mitigated and market comfort brought to fruition. This leveraging accelerates the pace at which development backlogs can be addressed. A second, complementary function of DFIs is their “development assistance” role. This function is additional, and often non-recoverable, but complements “development banking” by improving information flow, enhancing borrower capacity and improving the prospects of debt servicing. In this way, the banking and development assistance functions of a DFI become mutually reinforcing. DFIs value development per se, but also depend on the servicing of debt. Private financial institutions are concerned with repayments and enforce more onerous financial requirements (higher collateral, capacity and tenor) up front. DFIs bundle the “development banking” and “development assistance” functions together, since the skills required for assessing potential investment projects are similar to those required for addressing capacity building and development needs, and preparing borrowers for project lending. This implies the existence of 4 economies of scope in the provision of these two services. Of late, the emphasis on DFIs role as knowledge-brokers has also increased. The nature and role of development finance is continuously changing due to recent development in global capital markets over the last decade, global constraints on public finance, the narrowing definition and range of public goods and services, and the reduced direct role of the state in the market e.g. increasing privatisation. The borders between public finance on the one hand and private commercial finance on the other have become blurred thus shifting the nature, scope and role of DFIs in a rapidly changing macro-economic environment. Moreover experience with development finance and DFIs in the past has lead to scepticism of the efficacy of development finance especially where state owned banks were and are still used for non-commercial, quasi-fiscal purposes thus posing a risk to macroeconomic and financial sector stability of economies in transition (Sherif & Borish 2003)v. Development finance cannot compensate for deficiencies in regional and national policy gaps and institutional capacities, which make DFIs a weak mechanism for unfunded public sector redistributive mandates. The central intermediation function of DFIs requires employment of sound banking principles to ensure that scarce capital is obtained at an affordable cost and allocated efficiently, consistent with both risk and return (in development and financial terms). Cost-effective intermediation is key for DFI customers, who generally cannot afford high interest rates, and most often cannot access commercial bank services. Where nationally-based DFIs are required to be self sustaining, and must increasingly raise funds independent of government guarantees, they have to pay special attention to their credit ratings and adopt prudent risk management policies and practices. The outcome is that DFIs end up prioritizing their financing activities, and certain high risk segments of the market go unserved. However, some DFIs try to make up for this by establishing special-purpose grant and soft loan windows to help reach the unserved in a manner that does not compromise their basic functions and sustainability (DBSA, 2004)vi. The fundamental role of DFIs in the market economy is to crowd in private financial flows by providing a package of services that not only fill the fiscal gap between capital for pure pubic good finance provided by the state on the one side and pure commercial projects on the other, but also seek to narrow the gap in the finance system. Therefore national DFIs should not be permanently enshrined institutional structures; they should work towards successful transformation of both development financing and funding so that they are no longer needed. 3. The Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA): Background, Nature and Practice 3.1 Governance The legal aspects and corporate governance The DBSA is a development finance institution that was established in 1983 under the apartheid government to channel fiscal transfers from the South African central government to the so called 5 ‘homeland’ governments or Bantustans. It is wholly owned by the South African government. The Bank was created under an Act of Parliament, the DBSA Act, as amended in 1997. It does not fall under the Banks Act and is therefore not directly supervised by the Reserve Bank. It however complies with applicable provisions of the Companies Act and the Public Finance Management Act of 1999. The DBSA Act of 1997 (Act 13 of 1997)vii Articles 5 to 10 provide for the appointment of a Board of Directors and the governance of the Bank. The Act allows for the appointment of a maximum of 15 and a minimum of 10 directors by the shareholder(s). At present the Board of Directors consists of twelve members from the private sector and one from the public sector. (Until recently there were two public sector members.) Directors are appointed by the Minister of Finance and the Act requires that they “shall be appointed on the grounds of their ability and experience in relation to socio-economic development, development finance, business, finance, banking and administration.” All but one of the directors are independent and non-executive, with only the CEO/MD as the executive director. This majority of directors from the private sector indicates the ‘arms-length’ relationship between the South African The Public Finance Management Act (PFMA) government, as shareholder, and the Bank. lays a basis for a more effective corporate Article 5 (b) provides that the Board shall governance framework for the public sector. control the business of the Bank and shall direct The PFMA introduced generally recognized the operations of the Bank. In execution of their accounting practices; uniform treasury norms duties the Directors subscribe to the King II and standards; prescribed measures to ensure Report on Corporate Governanceviii and the transparency and expenditure in all spheres of Code of Corporate Practice and Conduct of the government; and set the operational procedures for borrowing, guarantees and Institute of Directors in Southern Africa procurement of services. The Bank reports on (IDOSA 2002)ix, and the Public Finance quarterly basis to the National Treasury in Management Act, No. 1 of 1999 (SA terms of the 1999) PFMAx.requirements. Unlike Government The Board is assisted in its strategic oversight by a number of functionally commercial banks, the DBSA is not subjectthe to Audit and Finance committee, the Credit Committee, focused Board sub-committees, namely: supervision by the Reserve Bank under the the Knowledge Strategy Committee and the Remuneration Committee. Although the DBSA does Banks Act, 1990, but provides specific not legally report the Reserve information to thetoSARB related toBank, its it nonetheless provides it with regular information regarding theand Bank’s funding and assetpolicies and liability management practices. borrowings currency management on a quarterly basis, or as and when required. Vision, Mission and Mandate The Vision of the Bank is “to be a leading change agent for socio-economic development in southern Africa”. The mission of the Bank, accordingly, has been “to contribute to development by providing finance and expertise to improve the quality of life of the people of southern Africa, mainly through the provision of infrastructure” The main objects and mandate of the Bank are provided for in the DBSA Act. Article 3 (1) notes that “the main objects of the Bank shall be the promotion of economic development and growth, human resources development, institutional capacity building (by mobilizing financial and other resources from the national or international private and public sectors) and the support of (sustainable) development projects and programmes in the region”. Prior to 1994, the Bank funded projects in all sectors which included agriculture, industrial development and small and medium enterprises. In the period between 1994 and 1996, the 6 Government streamlined the entire development funding system which resulted in the refocusing of the five national DFIs that narrowly constitute the development finance system: the DBSA on infrastructure; the Landbank on Agriculture; the Industrial Development Corporation on industry; Khula Enterprise on small and medium scale lending and the National Housing Finance Corporation on housing. Three further points from the Bank’s history are worth noting. During its first ten years, as a publicly funded body, it stressed its role of encouraging private sector lending by describing itself as a “lender of last resort.” Since 1994 the newly-elected ANC government supported the continuation and transformation of the DBSA with the intention that public sector borrowers, such as local authorities, must be subject to the discipline of the market. In 1995 Government ceased fiscal transfers to the DBSA and required it to be financially self-sustaining. For the DBSA, infrastructure is broadly defined to comprise economic, institutional and social infrastructure. Examples of economic infrastructure include water, sanitation, roads, drainage, telecommunications and energy. Like many of its peers, the Bank is mandated to accelerate the delivery of basic services and economic growth while maintaining financial sustainability as a means to achieving that goal. Consequently the Bank operates on sound banking principles and is required to manage any natural tension that may arise between these underlying principles. In order to galvanise the efforts of its interventions, the Bank has adopted further guiding principles, namely: partnerships (with government, private sector and civic society); innovation; risk taking and risk management; knowledge management; rewarding performance; and focus on mandate as agreed with the shareholder. 3.2 Products and Services The Bank offers a package of development banking and development assistance products and services, consisting of lending/investment; guarantees; grants and technical assistance; advisory services; research and policy. The Bank is predominantly a debt provider, but invests in equity instruments as guided by its risk management policies. In recent times, the DBSA has widened its scope of funding instruments to include investment banking products such as arranging syndication and underwriting roles. These represent powerful tools to crowd in the private sector and the wide network of bilateral and multi-lateral development partners. Within the key provision of the broad operational framework of the DBSA’s mandate the DBSA plays a triple role of financier (lender/investor), partner, and advisor to its clients. The figure below shows the relationship and complementarity of the roles. As a financier the DBSA thus fulfils its ‘development banking’ role on the one side, and as advisor its ‘development assistance’ role on the other. Recent developments in PPPs provide the scope for partnership with public and private institutions as either financier or advisor or both when transacting with the beneficiaries of development finance. The modalities by which DBSA executes its triple role are represented in the table below. Financier Partner 7 Advisor Fund mobiliser Grant-maker Lender Investor Under-writer Arranger Catalyst Leverage Agent Development Facilitation Policy analysis Advocacy Capacity building & training Research & Evaluation Development Information In fulfilling its developmental role in the region DBSA has achieved significant impact beyond its limited resources. It is not the intention of this paper to reflect on all these achievements in great details but to highlight lessons of best practice in the management of the key modes by which the Bank executes its development finance role. 3.2.1 Finance Lending and Investment Activities The Bank’s lending and investment instruments consist of fixed and floating rate loans on Rands as well as US dollar and Euros. In broader terms, the lending modalities are similar to those of other DFIs. The lending and investment operations of the DBSA are focused on infrastructure as previously noted. The guiding principles are that the projects and and programmes must be sustainable from a development impact and financial perspective. In arriving at a lending or investment decision, the appraisal process looks at a number of modules, namely: the economic, financial, technical, social, institutional and environmental. These modules are similar to those applied in multi-lateral development institutions. Risk management tools and practices are vigorously applied and weighted accordingly. As part of its development assistance, the Bank offers technical assistance targeted at addressing constraints at project or client level that may negatively affect the success of projects and programmes. Infrastructure projects are by nature long term, and cash flows are not always positive at the outset. The Bank plays a developmental role by offering long term loans that match the lives of the projects or underlying assets, while at the time structuring the project to crowd-in the private sector who might not be in a position to assume certain risks without the involvement of a DFI. In this regard, the DBSA regularly applies project finance and syndication techniques to encourage the participation of private sector. The Bank’s lending and investment operations extent to other SADC countries, but with an overall limit of one third of total portfolio. In the rest of the SADC region, the Bank finances not only projects of an infrastructure nature, but also economic growth sectors that are drivers of economic development plans of these countries. In addition, projects and programmes that promote the development of local capital markets are encouraged, and so is support to financial institutions through lines of credit. For South African based activities, the major clients are local authorities (municipalities) and utilities. Since 1996 the Bank established its private sector business as a means to partner with private sector in development projects. From a zero base, it has grown to a portfolio of diverse projects amounting to US$690,000, and represents one of the fastest growing parts of the Bank’s business. The spread of sector and country portfolios are 8 contained in its annual reports, but the following tables provide selected information in this regard. Banking principles Like most DFIs, the Bank has to balance sustainable development impact and financial sustainability, and therefore applies sound banking principles. The development finance (banker) role of the DBSA is the nexus of its long term sustainability and independence from periodic government recapitalisation of capital. Sound and prudent financial management has allowed the DBSA considerable leeway to cross-subsidise its advisory role and in some cases its knowledge partnership role. The rating agencies Fitch, Moody’s Investors Service, and Standard and Poor’s reaffirmed or upgraded the Bank’s investment grade ratings. Fitch reaffirmed the AAA domestic ratings, while the international ratings were upgraded by Moody’s in May 2002 from Baa3 to Baa2 with a positive outlook and from BBB- to BBB with a stable outlook by Standard and Poor’s. These ratings reflect, among other factors, strong shareholder support from the South African government, a solid financial position, and prudent risk management policies. The DBSA’s sources of funding are domestic and international financial and capital markets; international DFIs and partners; internal cash generation and callable capital of $700 millionxi. Among other factors, investment grade credit ratings put the Bank in a position to mobilise funds efficiently and costeffectively. As the Bank looks forward to raising its profile in international capital markets, these credit ratings underpin its borrowing strategy. The Bank’s regulations stipulate a maximum DebtEquity ratio for the Bank, of 250%. Capitalisation and funding The DBSA was initially capitalised by its shareholder and received fiscal transfers up until 1994 when these ceased to be the main funding tool. During the transformation of the national development finance system, certain of the Bank’s loan portfolios to the then “homeland governments” were taken over by National Government in exchange for liquid Government bonds but at a higher coupon rate. This effectively added another capitalisation layer. Furthermore in 1997 the Government committed itself to callable capital of R4.8billion to support the expansion of DBSA’s borrowing to fund its lending operations. The Bank has further strengthened its capital base through the net surpluses it has earned since inception. The Bank’s capital base now stands at around R11 billion (US$1.75 billion). Loan portfolio management The Bank maintains a portfolio balance to mitigate risk in terms of: Country spread. Sector spread. Single obligor limits. 9 Country limits are reviewed on an annual basis and presented to the Board of Directors for approval. The Banks policy is that the total exposure to SADC countries (excluding South Africa) should not exceed 33% of the Bank’s portfolio. As at 31 Multi-State December 2003 the Botswana cumulative loan and equity Malawi approval by country are reflected in the table below. Lesotho Mozambique South Africa Namibia Swaziland The Bank’s exposure to countries outside South Africa was 26% and within the limits set by the directors. Zimbabwe As at 31 December 2003 the Bank’s cumulative loan and Zambia equity approval sectoral spread of projects is reflected in the table below Sector Commercial Communications Transportation Education Energy Residential Facilities Roads & Drainage Sanitation Social Infrastructure Water TOTAL ZAR ‘000 4,828 1,535 13 1,632 6,270 349 5,056 2,171 821 6,609 29,284 US $ ‘000 690 219 2 233 896 50 722 310 117 944 4,183 Commercial Communications Transportation Education Energy Residential Facilities Roads & Drainage Sanitation Social Infrastructure Water 10 16.50% 5.20% 0.00% 5.60% 21.40% 1.20% 17.30% 7.40% 2.80% 22.60% Msunduzi Urban Development Programme The DBSA policy thus ensures a portfolio As part of its drive to extend municipal services to the previously spread between various disadvantaged areas, the Msunduzi Municipality (formerly sectors and countries. In Pietermaritzburg TLC) designed an infrastructure renewal programme, the rest of the SADC called the Msunduzi Urban Development Programme. The programme region, the Bank’s was divided into phases, and involves the development and extension of lending and investment infrastructure in three key sectors – roads, electricity, water and programmes are limited sanitation. to a third of the Bank’s maximum possible For a start, the municipality used its own capital budget, but had to borrow because of the magnitude of the programme. The DBSA was exposure. Unlike multiapproached towards the end of 1997, and gave approval for the first loan laterals such as the in 1998. Phases I and II were completed in 1999 and 2000 respectively. IBRD and the AfDB, By December 2002, the Bank’s financial contribution to the whole the Bank’s operations in programme was R154.3 million. Meanwhile, work continued on the SADC are not all remaining phases of the programme. guaranteed by the respective governments, nor does the Bank enjoy preferred creditor status. It operates through memoranda of understanding, and within the context of treaties and other bi-lateral agreements between South Africa and these countries. The third portfolio management policy that has been approved by the Directors is not to expose the Bank unduly to single obligators. The single obligor limit is 10% of shareholders interest including the R4.8 billion callable capital for South Africa. The public sector single obligor limit for clients situated outside South Africa’s borders is 10% of shareholder’s interest excluding callable capital. Lastly, no more than 10% of shareholders interest may be invested in equity / quasi-equity in aggregate. Interest rate policies Interest rate policies are a contentious issue, however interest rate subsidies to clients tends to distort financial markets and crowd out local and foreign direct investment. Client subsidies are better applied through the development assistance functions of DFIs, such as the DBSA’s advisory (capacity building) and partnership roles. The DBSA policy is thus to charge market related interest rates and rather create comfort for private capital through its higher risk appetite and prepare borrowers to take up project loan financing. The interest rates applied to DBSA project finance are determined in accordance with the Bank’s interest rate policy, approved from time to time by the Board of Directors, and are implemented by executive management. This policy determines, inter alia, that lending rates are based on the cost of funding plus a margin for risk, and an internal overhead charge Risk management The Bank’s pursuit of best practices in risk management has stood it in good stead. In the development of its risk management policies and methodologies it has consistently endeavoured to benchmarkxii against best practice in the development finance industry as well as others in the banking industry. Additionally, the Bank engaged consultants to benchmark its risk management 11 practices against international best practice. This was done using grant financing provided by the World Bank. The results of these efforts include: Maintenance of the quality of the loan book; The low rate of defaults experienced by the Bank; Efficient and effective workout procedures when defaults have occurred; The contribution made by risk management to the credit rating agencies’ assigning premier ratings to the Bank; The Bank’s low cost of funding. 3.2.2 Partnerships Smart Partnerships In its engagement with NEPAD, Africa south of the Sahara, and more specifically SADC a strategic thrust of the DBSA is to establish smart partnerships with multi-lateral and bi- lateral development finance agenciesxiii on the one hand and knowledge partners as part of its advisory role on the other side. In line with this thrust, the Bank continues to act as a catalyst and facilitator to draw in and complement the involvement of as many relevant development partners as possible. The DBSA is well placed to play the wider role of a trusted regional development partner and advisor in strategic support of various developmental processes. Its partnerships role helps reduce transaction costs and risks through better knowledge management and capacity building, and enables the realisation of synergies and positive externalities, thus achieving developmental leverage beyond its own means. This is consistent with present efforts by leading development agencies and further enhances the role of non-traditional partners in development, such as the private sector, regulators and civil society. As a catalyst for regional integration and development the DBSA as a smart partner has achieved leverage beyond its limited means (DBSA 2003). The Mozal aluminium smelter near Maputo is the biggest industrial development project ever undertaken in Mozambique. The total cost of Mozal I and II is estimated at $2,2 billion, and the DBSA has provided financing to the value of $103 million. The smelter will produce 2 per cent of the world’s annual consumption. The Bank became involved in order to support the Maputo Development Corridor and the economic development programmes of Mozambique and the region. This decision has been justified by the performance of Mozal I, which has made a major contribution to the regeneration of the Mozambican economy. Investor confidence in the country has risen significantly, and the prospects for further investment are strong, with a number of substantial projects in the pipeline. Mozal I has contributed around $160 million per annum to the country’s GDP, generated export earnings of $430 million per annum (an increase of more than 150%), and added about $4 million per annum to tax revenue. The Mozambican government’s shareholding in the first phase has generated dividend income of $5 million per annum. The economy has also benefited from the establishment of related infrastructure, including improved roads and bridges, telecommunications networks, water and sewage systems, upgraded harbour facilities and electricity supply. Mozal has initiated an innovative social development programme, implemented through the Mozal Community Development Trust, to provide support for communities within a ten kilometre radius of the smelter. The company funds the Trust to the tune of $2 million per annum. The Trust focuses on small business development, agriculture, education and training, health and the environment, culture and sports, and community infrastructure. Various projects are already being implemented and others are under consideration. (NEPAD / DBSA 2003 b)xiv 12 Agency Services As the Bank has become known for its institutional capacity, there have been more and more requests for it to play an agency role implementing projects on behalf of others. These requests come from institutions such as governments, donors and other development stakeholders, who lack the specific local and regional capacity to implement programmes. The Bank, in turn, has increasingly recognised that it needs to play a more enabling role in development. The idea of providing agency services has therefore developed over time, and is now included in the Bank’s range of standard products. Agency activities allow the Bank to enhance development in South Africa and the rest of the continent by negotiating new partnerships and strengthening existing ones with other development stakeholders. Currently, the Bank has 22 agency projects on its books, with a funding value of some $7million in financial year 2002/03. These projects are diverse in nature and include joint ventures, independent contractor assignments and management contracts. Some of the important agency functions are the African Connection project, the Carbon Finance Intermediary Agreement (with the World Bank), the International Development Research Council (sponsored by the Canadian Research Centre), the Environmental Capacity Building Unit (with the South African government), the Job Creation Trust, the Timbuktu Manuscript and Infrastructure Restoration Project (with the governments of Mali and South Africa), and the Low Cost Housing Infrastructure Fund (funded by Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau). 3.2.3 Advisor As an advisor the DBSA performs an important role of providing development assistance to its clients to address shortcomings in borrower institutional capacity. The DBSA strengthens the capacity of its clients to take up loan finance from the DBSA. By capacity building is meant institutional capacity to manage projects in terms of good governance, the systems in place, both organisational procedures and management information hardware and software, and individuals’ knowledge and skills development to support sound project investment and achieve significant impact. To achieve this the DBSA places much emphasis on sharing lessons learned, through knowledge management, hands-on capacity building and other forms of technical assistance. Knowledge management As an advisor the DBSA is focusing on positioning itself as a knowledge institution and centre of excellence in Africa south of the Sahara. A knowledge organisation, as defined by the DBSA, is: an organisation that values, generates and shares knowledge; applies and internalises knowledge in business processes and client-focused products and services; pursues focussed knowledge outreach to stakeholders; and has the architecture and infrastructure which capacitates the organisation for learning and leveraging skills and information. The DBSA has therefore established an organisational structure which gives equal importance and standing to its knowledge cluster as its other functional clusters, e.g. operations, private sector investment, treasury and special projects. 13 Development banking has always been a knowledge-based business, but this has been largely implicit in the past since the skills required for assessing potential investment projects are similar to those required for addressing capacity building and development needs, and preparing borrowers for project lending. As a regional organisation DBSA is uniquely endowed with a developmental track record of 20 years. With the recent development of frameworks for knowledge management, and the more explicit recognition that the Bank has a huge pool of development finance knowledge, a concerted effort is being made to recognize and characterize the knowledge that the Bank possesses, and put structures and processes in place to enable its widespread exploitation. This is especially important as the DBSA’s own triple role of financier, partner and advisor has matured. The approach has been to build solid foundations for the sustained delivery of knowledge, by firstly improving internal capabilities to deliver on the knowledge vision and then to deploy the extensive, domain-specific knowledge that the Bank has built up, as widely as possible through its marketplace. The DBSA Knowledge Strategy … conceptualising, nurturing and driving four dynamics … 1 Initiation and Embedding of “Learning Organisation” Culture and Dynamics 2 3 Development of “Knowledge” Products and Services and Embedding knowledge in Internal Systems and Processes Establishment of Organisational Architecture to Develop Internal Synergy and Leverage Skills and Knowledge for the Organisation 4 Establishment of Resources, Infrastructure, Systems and Processes to Support Learning Organisation Dynamics and Information Flows Via Formal Programmes in Five Strategy “Pillars” The Bank has developed formal knowledge programmes in five key strategic areas or “pillars”: Propagating and entrenching a knowledge culture in the organisation. Becoming a learning organisation. Exchanging and sharing knowledge in communities of practice and stakeholders. Knowledge accounting through evaluation and assessment of effective deployment of knowledge. Building smart institutional partnerships for knowledge building and brokering. The DBSA thus continues to invest in knowledge networks and communities of practice within and outside the organization. It is currently setting up and operationalising a specialized training academy, and working closely with various partners such as universities and multilateral and bilateral development agencies to tackle key social, financial and technological challenges of development and knowledge economies. The DBSA further seeks to supplement its own efforts and comparative advantages with the complementary strengths of various other role-players, leveraging collective resources, experiences and expertise. 14 The DBSA Development Fund A further intervention by the Bank to assist its clients is the establishment of the DBSA Development Fund. This is a non-profit company incorporated in December 2001 to address sustainable capacity-building in South Africa at municipal level, and to support municipalities in enhancing service delivery and local economic development. The core business of the Development Fund is to maximise the impact of development finance by mobilising and providing grant funding to address human, institutional and financial constraints on rural and urban development, thereby promoting effective service delivery and local economic development. This is done through a mix of products and services, including: Funds: Supporting capacity building funding through grants, development credits and other financial instruments. Expertise: Consulting and advisory services for institutional and human capacity building to ensure that basic services are delivered to disadvantaged communities. Development facilitation: Ongoing technical support and sharing of knowledge to ensure that clients gain the necessary experience to manage the functions and processes of service delivery. With the Fund operational in all nine provinces of South Africa, progress has been made in helping local government institutions to build capacity and formulate integrated development plans. The Fund approved technical support grants to 134 municipalities and provincial departments totalling $1,1 million in its first year of operation and has now been capitalised with the transfer of US$50 million from DBSA operational surpluses. Technical assistance Through its Operational units the DBSA frequently provides Technical Assistance to its clients for project preparation to the point where a bankable project proposal is submitted to the Bank for consideration for development finance. 3.3 Development Impact Through its sound governance, fiscal and outreach policies the DBSA has achieved considerable impact in the region. The table below contains the standard set of indicators that DBSA uses in its Annual Report. This table specifically illustrates DBSA’s contribution, over the last ten years, to employment creation and the impact of investments on low income households. The table illustrates how the Bank looks beyond its financial performance and evaluates its development impact in South Africa and the region, as required by its shareholder and directors. Project Funding ($ million) Contribution to GDP ($ million) Employment creation (numbers) Skilled (numbers) Semi-skilled (numbers) Unskilled (numbers) Impact on low income households ($mill.) Total approvals including co-funders $10,889 $7,940 527,874 51,250 227,027 249,597 $968 15 Total DBSA loans approved $3,723 $2,176 143,904 15,355 63,100 65,449 $328 The DBSA leverages or crowds in third party funding into the development process. This partnership approach over the past ten years, led to a $1 to $3.4 participation ratio with the DBSA approving projects to the value of $3,723 million and co-funders $7,166 million. Furthermore, projects supported by DBSA have contributed $7,940 million to the region’s GDP over the last ten years. Unemployment in the region is a concern and through its funding DBSA has contributed to parttime and permanent employment in the region. The table indicates the impact of disbursements on the income of low income households. The impact is considerably smaller than the impact on GDP because of the capital intensive nature of most infrastructure projects. In the final analysis the table once more indicates the leverage DBSA achieves in mobilising other sources of finance through structuring its package of financial services to crowd in foreign and domestic direct investments. 4. Ongoing challenges: balancing priorities The environment in which the DBSA operates creates certain tensions between the triple roles of financier, partner and advisor giving rise to a number of challenges in the wise management of the DBSA by its directors and executive in balancing priorities. Where nationally-based DFIs are required to be self sustaining, and must increasingly raise funds independent of government guarantees, they have to pay special attention to their credit ratings and establish risk management policies and practices to secure these. The intermediation function of the DBSA as a development banker requires employment of sound banking principles to ensure that scarce capital is obtained at an affordable cost and allocated efficiently, consistent with both risk and return (both developmental and financial returns). While the objectives and mandate of the DBSA are clearly developmental, tensions arise on the one hand with the need for the Bank to retain its favourable credit ratings, and on the other to deliver developmental outcomes such as uplifting neglected areas, combating poverty, creating employment etc. A careful balance must be struck between investments with high returns and less secure or attractive investments in pursuit of Government’s development agenda. Balancing costeffective intermediation, risk management and outreach through continuous strategic analysis, careful financial modelling, review of key performance areas, and value engineering have become crucial management functions of the organization and its executive. There is also a tension in the imperative to crowd in private sector lenders. Ideally a DFI should not compete with the private sector where the private sector is willing to invest. However the need for the DFI to have some good quality loans in its book means that this needs to be managed carefully in order to avoid discouraging private sector investments. When a DFI has a number of financial products such as special-purpose grants and soft loan windows, such as the DBSA Development Fund, it needs clear policies on when to use each in order to reach the unserved in a manner that does not compromise the basic functions and sustainability of the DFI. In the same vein, a DFI can use these products (in appropriate amounts) 16 and its knowledge role to build capacity among hitherto non-bankable potential clients and so “graduate” them to a position where they can take up loans from the DBSAxv, thus increasing the Bank’s loan book and scope of its development finance operations. 5. Policy conclusions An overview of the development finance system and the background, nature and practice of the DBSA in addressing development challenges leads to a number of guiding principles for the successful management of DFIs. These include: Governments must provide an environment that is conducive to the development of financial markets, e.g. in Africa the NEPAD emphasises transparency and good governance as crucial for Africa’s recovery. DFIs need autonomy of governance to maintain an arms-length from both governments and their clients. Prescriptions on who to fund, and on what financial terms and conditions lead to ineffectiveness, weakening of the DFIs ability to raise private capital, and crowding out private capital. DFIs should have the flexibility to focus on regional and local circumstances as development partners with multilateral and bilateral agencies, as the former have a better understanding of local and regional developmental risk and are able to match their risk appetite accordingly. DFIs can achieve enormous leverage beyond their capitalisation by establishing smart partnerships with multilateral and bilateral agencies, private capital, knowledge institutions and NGOs. Prudent management of systemic risk requires that DFIs manage diversified portfolios. The sustainability of DFIs depends on them spreading risk across different types of clients and sectors. Interest rates and tenor should be market-related to avoid crowding out private capital. Client subsidies are better applied through the development assistance functions of DFIs, such as advisory services and capacity building. DFIs should be subject to strict commercial norms and practice. Systemic risk as related to funding structure (as reflected in balance sheet ratios) should be minimised by applying commercial risk principles. Public subsidy-dependent key performance areas and sectors, e.g. basic social services in the DFI portfolio should generally be pursued as an off-balance-sheet ‘agency’ arrangement entered into with the relevant government ministries or multilateral and bilateral donors. For DFIs to succeed within the rapidly changing global and regional environment they must meet a number of challenges for their effective management. This requires sound governance and financial management, flexibility, and an ability to balance cost-effective intermediation and risk management with outreach through smart partnerships, capacity building and knowledge management. 17 Endnotes i World body endorses NEPAD: UN negotiations bring agreement to back African initiative. Africa Recovery, Vol.16#4 (February 2003), page 6. ii Diamond, W.1957. Development Banks, John Hopkins Press, Baltimore. iii Hoffmann, S L. 1998. The Law and Business of International Project Finance. London: Kluwer Law International. iv Mistry, P, Realigning the development finance system in South (and Southern) Africa: Issues and options, Undated Mimeo, Development Bank of Southern Africa, Midrand, South Africa. v Sherif, K & Borish, M, 2003. State - Owned Banks in the Transition: Origins, Evolution and Policy Responses by Alexandra Gross , World Bank 2003. vi DBSA, 2004, Ten year review. Work in progress draft, Development Bank of Southern Africa, Midrand, South Africa. vii DBSA Act of 1997 Act no. 13 of 1997. viii King Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa 2002 (King II Report). Institute of Directors in Southern Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa http://www.idosa.co.za ix Reviews of the effectiveness of the Board were conducted during the 2003/04 financial year in line with the King II recommendations and the Board Charter. x South African Public Finance Management Act. 1999. http://www.gov.za/acts/1999/a1-99.pdf xi 2004 prices. xii The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) loan pricing spread resemble that of DBSA. The IFC currently applies lending spreads for projects at a range from a low of 125 basis points to a maximum of 500 basis points. The AfDB aggregates its risk pricing also to a maximum of 500 basis points for unsecured private sector loans in high risk countries. xiii e.g. AfDB, EIB, KFW, CfD and World Bank projects and Agencies. xiv NEPAD/DBSA, 2003. Financing Africa’s Development: Enhancing the role of private finance. Development Report 2003. DBSA, Midrand, South Africa. xv E.g. borrowers do not have the capacity to absorb development finance, so DBSA established the Vulindlela Academy and Knowledge Portal, but this still needs to be rolled out to SADC and NEPAD. 18