GENERAL BIOLOGY LAB 1 (BSC1010L)

advertisement

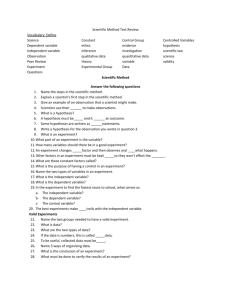

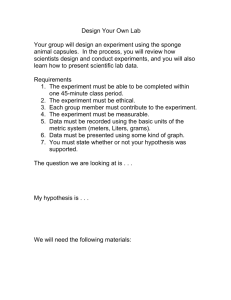

Exercise 1: Introduction, Scientific Method & Measurements I ______________________________________________________________________________ OBJECTIVES: 1. Familiarize yourself with lab policies and practices 2. Learn and practice the scientific method 3. Learn about accuracy vs. precision 4. Learn about the use of basic statistics _____________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION: Science is a way of acquiring new knowledge to understand the world around us. Scientists approach all natural phenomena using standardized deductive reasoning, more commonly referred to as the scientific method. The scientific method may be expressed as a series of steps: 1) making observations, 2) creating questions, 3) forming hypotheses, 4) conducting empirical tests, 5) quantifying data, 6) testing hypotheses, and 7) drawing conclusions (Fig. 1), each of which will be discussed in further detail and implemented throughout the semester. In this course, you will learn and apply the underlying principles and techniques used by scientists to gather data of basic biological processes. You will also gain an overall understanding of how this knowledge is used in areas ranging from the development of treatments for diseases to the effects of global warming on our planet. In addition, this lab will introduce you to basic techniques required to perform experiments later on in the semester. ______________________________________________________________________________ A GENERAL NOTE ON PERFORMING TASKS IN THIS COURSE: In any experiment, wait for your TA to describe or demonstrate the proper procedure before starting. Never perform an experiment unless you are sure about what you are doing. If you have any questions, it is much better to ask than to proceed incorrectly and fail or cause danger to yourself or others. ______________________________________________________________________________ Task 1 - SAFETY: Learn about safety in a biology laboratory. 1. Review the lab safety handout with your instructor. 2. Note the location of each of the following safety equipment/items a. Shower ___________________________________________________ b. Eyewash___________________________________________________ c. Medical emergency procedure__________________________________ d. Fire extinguisher_____________________________________________ e. Emergency gas cut-off valve___________________________________ f. Phone_____________________________________________________ 1 Task 2 - THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD The scientific method is a way of posing questions about the natural world that can be tested through repeated and unbiased experiments. It is a highly effective process for solving problems and answering questions. Generally, the scientific method includes the following steps: Figure 1. The Scientific Method The scientific method begins with a question about a particular phenomenon; for instance, the role of smoking in lung cancer. After conducting background research and learning more about the subject of interest, a scientist formulates a possible explanation for the phenomenon i.e., a hypothesis. Hypotheses are always phrased as statements, not questions. In formulating a hypothesis, assumptions are stated and a tentative explanation is proposed. In the lung cancer example above, the general hypothesis is that smoking causes lung cancer. It is important that hypotheses are falsifiable. In other words, based on the results of the data collected, a hypothesis is either retained or rejected. The results can never “prove” the hypothesis, but can lead to the conclusion that it cannot be rejected. To ensure that results obtained are not erroneous (such as false positives or false negatives) due to random chance, we need to consider alternative explanations. In the case of 2 our lung cancer example, an alternative explanation would be that lung cancer is caused by something else, not smoking (i.e. smoking does not cause lung cancer). In lieu of this, scientists formulate two types of hypotheses: 1) a null hypothesis (Ho), and 2) an alternative hypothesis (Ha). Note that Ho and Ha are always paired. Ho states that any relationship found between treatments is due to random chance, while Ha predicts that a relationship actually exists (i.e., the exact opposite of Ho). In essence, Ho is a statement that we are trying to nullify/falsify in favor of the Ha. In the lung cancer example, Ho: Smoking does not cause lung cancer Ha: Smoking causes lung cancer In order to test the hypotheses generated, an experiment needs to be designed. A plausible experiment to test Ho and Ha above might be to track groups of smokers and non-smokers and compare the occurrence of lung cancer in each group. Predictions about the experimental outcomes are then made using if-then statements; if the data supports Ho, then we should not observe a higher incidence of lung cancer in smokers, compared to non-smokers. In other words, if no observable differences between smokers and non-smokers are noted, then we fail to reject Ho. Whether a hypothesis can be tested is dependent on how well an experiment is designed. A good experiment should have all variables identified and proper controls to limit extraneous influences. A variable is anything that is controlled, manipulated or measured. An independent (experimental) variable is the one that is manipulated during the experiment while the dependent (response) variable changes in response to the independent variable. Controls are a crucial component of every experiment and are kept constant throughout the experiment in order to examine the impact of the independent variable. In the lung cancer example, smoking is the independent variable while the occurrence of lung cancer would be the dependent variable. The control in this case would be a group of non-smokers. Using the Scientific Method A. Description of the Problem You will work through this exercise in your groups, periodically coming together as a class to explain your reasoning and to decide on how to proceed with the remainder of the task. Your assignment is to develop a scientific hypothesis and test it. The topic will be neuromuscular reaction time. This can be easily determined by measuring how quickly a person can grasp a falling meter stick and will be recorded as millimeters (mm) free fall. Procedure: The person whose reaction time is being measured (the subject) sits at a table with her or his forearm on the top and the hand extended over the edge, palm to the side and the thumb and forefinger partially extended (Fig. 2). A second person holds a meter stick just above the extended fingers and drops it. The subject tries to catch it. The distance the meter stick drops before being caught is a measure of the subject’s reaction time. 3 Figure 2. Measuring reaction time Your assignment is to generate a scientifically testable hypothesis regarding reaction time in individuals with different characteristics. Remember that a null hypothesis (Ho) is always paired with an alternative hypothesis (Ha). You will then design an experiment to test the hypothesis, collect and analyze the data, and decide whether to reject or fail to reject your Ho. For example, you might investigate if there are differences in reaction times between those who play musical instruments and those who do not, if there are gender differences, or if differences exist between right and left-handed individuals. The design will depend on the hypothesis that you decide to test as a class. B. Summarizing Observations 1. As a group, begin your discussion of this assignment by summarizing all possible questions to answer. Are neuromuscular responses the same for all people or might they vary by athletic history, gender, body size, age, hobbies requiring manual dexterity, left versus right hand, or other factors? For example, you might expect differences in the physiological responses of those who exercise. What other factors might influence the response time? C. Asking Questions 2. Research starts by asking questions which are then refined into hypotheses. Review the group observations that you listed above and write down scientifically answerable questions that your group has about reaction time in people with different characteristics. Present your group’s best question to the class. D. Forming Hypotheses 3. As a class, review the questions posed by all groups. Examine the questions for their answerability. As a class, you will now vote on the best question that all groups will examine. Write that question in the space provided below. In addition to the question decided on by the class, you will determine if the size of a person’s hand affects reaction speed (distance from beginning of the palm to tip of the middle finger). 4 4. In your group, state the question above as a prediction. For example, because piano players constantly train their neuromuscular reaction time, you might expect that they would have short reaction times. Use this prediction as a basis for forming a testable hypothesis. Continuing with the example, you might propose for a hypothesis that there would be no significant difference between piano players and non-musicians in reaction time. The alternate hypothesis would be that there is a significant difference between musicians and non-musicians. Remember that hypotheses must be testable through experimentation or further data gathering. State Ho and Ha below. a. Describe what makes your Ho testable. b. State the hypothesis testing if the size of one’s hand affects reaction speed: E. Designing an Experiment To test a hypothesis, a controlled experiment must be devised. It should be designed to collect evidence that would prove the hypothesis false. Discuss the design of the experiment to be performed including the variables below. 5. What are the variables in your experiment? a. Which of the variables is (are) the independent variable(s)? b. Which of the variables is (are) the dependent variable(s)? c. What variables will be controlled and how will they be controlled? 5 6. Having decided which variables fit into these categories, you must now decide on a level of treatment and how it will be administered. How will you standardize measurements across groups in the lab so that the results are comparable? 7. Recognizing that the subject may anticipate the dropping of the meter stick or be momentarily distracted when it is dropped, how many times will you repeat the experiment to have confidence in your results? 8. Present your group design to the class. Consider the experimental designs proposed by other groups. As a class, vote on an experiment that best tests the hypothesis. Note the experimental design below. Make sure that each person in the group serves as a subject. F. Procedure 9. As a class, write a protocol describing about how the experiment will be performed. All groups will follow these procedures. Also, design a table in which you will record your data. Put the procedures and data table in the space provided. 6 10. Perform the experiment as a group. G. Data Recording 11. Combine your group results with those from the other groups to generate a class dataset. Make sure to copy all of the data for analysis. Record all the data in the space below. 7 H. Data Summarization 12. Graph your data to investigate the relationship between your independent variable and reaction speed for each experiment. Divide the space below into two graphs to display the data for each hypothesis (hand size and variable determined by the class). Note: The independent variable is plotted on the horizontal (x) axis while the dependent variable is plotted on the vertical (y) axis. 8 I. Data Interpretation 13. Write a few sentences that summarize the trends that you see in the data. J. Conclusion 14. Return to the hypotheses (Ho and Ha) that were formulated at the beginning of the experiment. Compare them to the experimental results. Do you reject or fail to reject the hypothesis? Why? Cite the data used in making the decision. K. Discussion 15. As you conducted this experiment and analyzed the results, additional questions probably came into your mind. As a result of this thinking and the results of this experiment, what do you think would be an interesting hypothesis to test if another experiment were to be done? 16. Evaluate the design of your original experiment. Be as critical as you can. Were any variables not controlled that should have been? Is there any source of error that you now see but did not before? Note: In any experiment there is “error”. Error is the difference between a measured value of quantity and its true value. It is not a "mistake". Variability is an inherent part of things being measured. 9 ______________________________________________________________________________ Task 3 – DATA COLLECTION: Accuracy vs. Precision When taking scientific measurements both accuracy and precision need to be considered. Accuracy is the exactness of a measure whereas precision is the ability of an instrument to repeatedly provide a measure. In the example below (Fig. 3), arrows that land closer to the bull’s eye are considered more accurate than those landing further away, while arrows that cluster tightly together in a particular area of the target are more precise than those scattered about. Figure 3. Precision is the ability to consistently hit the same area of the target, while accuracy is how close you come to the center of the target. In the lab, scientists use a balance/scale to measure mass in grams (g), however the number of decimal places reported varies from scale to scale. The scale’s accuracy is determined by how close its measurement of an object’s mass is to the object’s actual value. If greater accuracy is required, a scale that provides further definition should be used, i.e., one that reports a greater number of decimal places. In contrast, when referring to precision, we are talking about how well the scale performs, i.e., its reproducibility or ability to consistently give similar mass measurements every time the same object is weighed. Procedure: 1. Your TA will demonstrate how to correctly use the tools for measuring volume that are at your station. 2. Use the 5mL pipette and 100mL beaker (filled with about 25mL of water) at your table to practice using the pipette. 10 3. Your TA will now demonstrate how to use the balance. Make sure you learn and understand how to “zero” the balance. Note: The process of subtracting the mass of the device holding a substance from the mass of the substance plus the holding device is called taring. When you zero the scale, you are taring. 4. Weigh an empty, 100mL beaker. Mass of beaker alone = __________. 5. Using a graduated cylinder, fill the beaker with 25mL of water and weigh it again. Mass of beaker + water = ________. Note: When reading the amount of liquid within a container, you must consider that liquids tend to adhere to the sides of the vessel where they are. When liquid does this, it forms a meniscus (Fig. 4). Readings should be taken at the bottom of the meniscus. Meniscus Figure 4. Meniscus of a liquid-filled graduated cylinder 6. Subtract the mass of the beaker alone from the mass of the beaker with water for the mass of the water. Mass of water = ________. 7. Empty the beaker again and use a pipette to add the following volumes of water in milliliters to your beaker: 5.0, 4.5, 4.3, 4.2, 4.0, 3.5, 3.3, 3.2, 3.0, 2.5, 1.5, 1.0 (this should equal a total of 40mL). We will now check the accuracy of the pipette by weighing the water and using the density of water to calculate volume. Density = mass per unit volume (mass/volume). The density of water at room temperature = 0.998g/ml. 8. Weigh the beaker with the water added. Mass of beaker + water = _________. 11 9. Subtract the mass of the empty beaker (you measured this previously) from the mass of the beaker with the water. Mass of water = _________. 10. Divide the mass of the water in the beaker by the density of water to get the volume of water in the beaker. Volume = __________. Question: Is the volume more or less than 40mL? If it is not the same, what can we say about the precision and accuracy of the pipette? 11. Calculate the experimental error using the following formula: % error = [(actual value – theoretical value)/ theoretical value] x 100 % error = ________________ 12. What does a positive error value mean? What about a negative value? What are some sources of possible error? 13. If you did the same experiment but instead you added two 20mL portions, do you think the error would change? Why? 12 Because there is usually some degree of error introduced when we take measurements, scientists take multiple readings and then use statistics to get a more accurate representation of the true measurement to evaluate how accurate the sampling was. Some frequently used statistical measures include mean (arithmetic average of a group of measurements), median (middle value of a group of measurements), and mode (most frequently occurring number in a group of measurements). In addition, range, variance and standard deviation can be used to measure variability. Range = absolute difference between lowest and highest value in the data set Variance = [sum (measured value for each sample – mean)2] / (sample size -1) = ∑ (x-x)2 N-1 Standard Deviation = √variance 14. Using the values in the Table 1, perform all calculations necessary to obtain the variance and standard deviation for the example data set. Table 1: Measure Collected 15 20 25 16 20 24 10 20 30 Sum (∑) = Sample Size (N) = Mean = Measure - Mean (Measure – Mean) 2 ∑= N – 1= Variance = Standard Deviation = 15. We will now apply what you have learned about the use of general statistics towards examining the data you collected using the pipettes. Each group will select one person to go to the board to write down the value you calculated for water volume using density. 16. Copy the data on the board in Table 2 and compute all listed variables. 13 Table 2: Group Water vol. (ml) 1 2 3 4 5 6 ∑= Range = N= Mean = Measured vol. – Mean vol. (Measured vol. – Mean vol.) 2 ∑= ∑/ (N -1) = √∑/ (N -1) = 17. Do the values between each group differ? If so, is any value very different from the others? If yes, check these for possible errors. If you can determine there was a gross error, you can then feel comfortable about eliminating that particular data point from your data set. Look for outliers and check them to make sure they are not legitimate measures. Sometimes outliers are true measures, but sometimes they are not. If determined not to be a true measurement, those data points should be discarded. However, if the outliers are true measures, then we should keep them. If your group does reject any data, write down the reasons for rejection in the space provided below. 18. Calculate the mean for water volume and record this value in Table 2. Questions: a. Is this value closer to the theoretical value of 40mL than the individual measurements? Why? b. Is the range a good measure of the variability of the data? If you used proper lab technique, should the range be small or large? Why? 14