View/Open - Cardinal Scholar

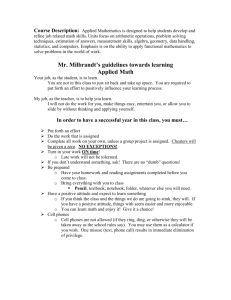

advertisement