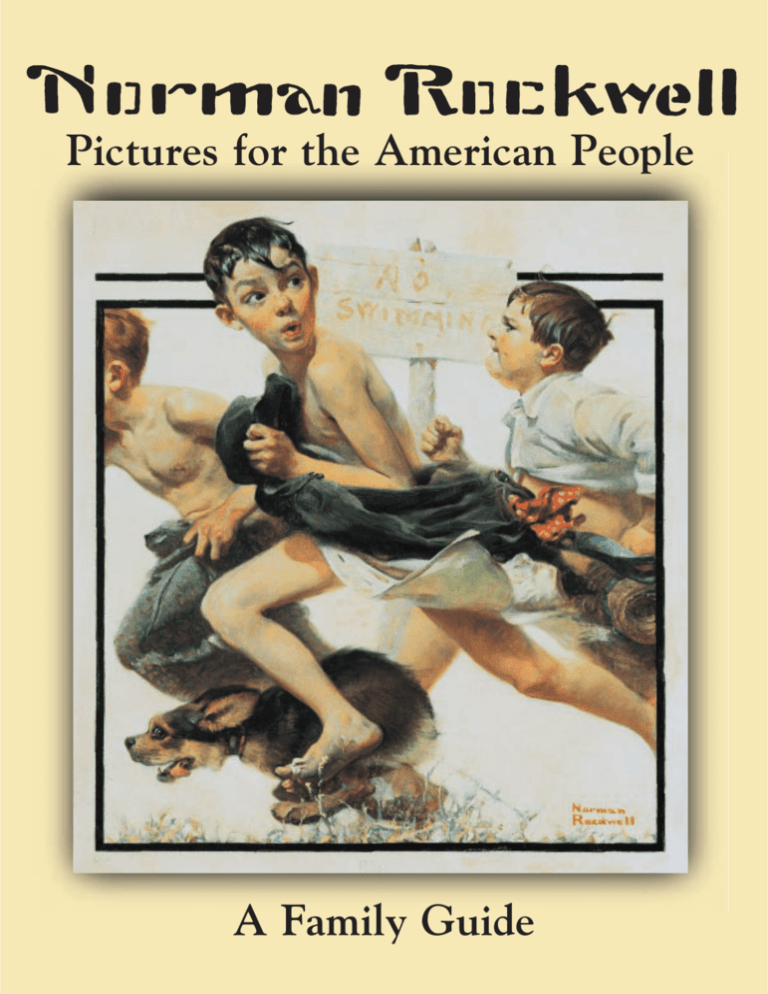

Pictures for the American People

A Family Guide

Norman Rockwell’s paintings...

Rockwell was born in New York City on February 3,

1894. When he was nine years old, his family moved

to the small town of Mamaroneck, New York. He was a

skinny boy and not very athletic, so he chose drawing

as his hobby. At age eighteen, Rockwell became art

editor of Boys’ Life, the official magazine of the Boy

Scouts of America. When Rockwell was twenty-two

years old, one of his paintings appeared on the cover of

The Saturday Evening Post, which showcased the works

of the finest illustrators of the period. Remarkably, in

forty-seven years, 321 of his paintings appeared on the

cover of the Post, making him one of the most famous

painters of the twentieth century.

Norman Rockwell created paintings to be enjoyed by

everyone. Many fine artists create paintings and

sculptures for private collectors, and sometimes this

artwork is not shown to the general public. Rockwell’s

paintings were seen across America, as they appeared

in books, advertisements, calendars, and on the covers

of popular magazines, such as The Saturday Evening

Post, Look, and Ladies’ Home Journal.

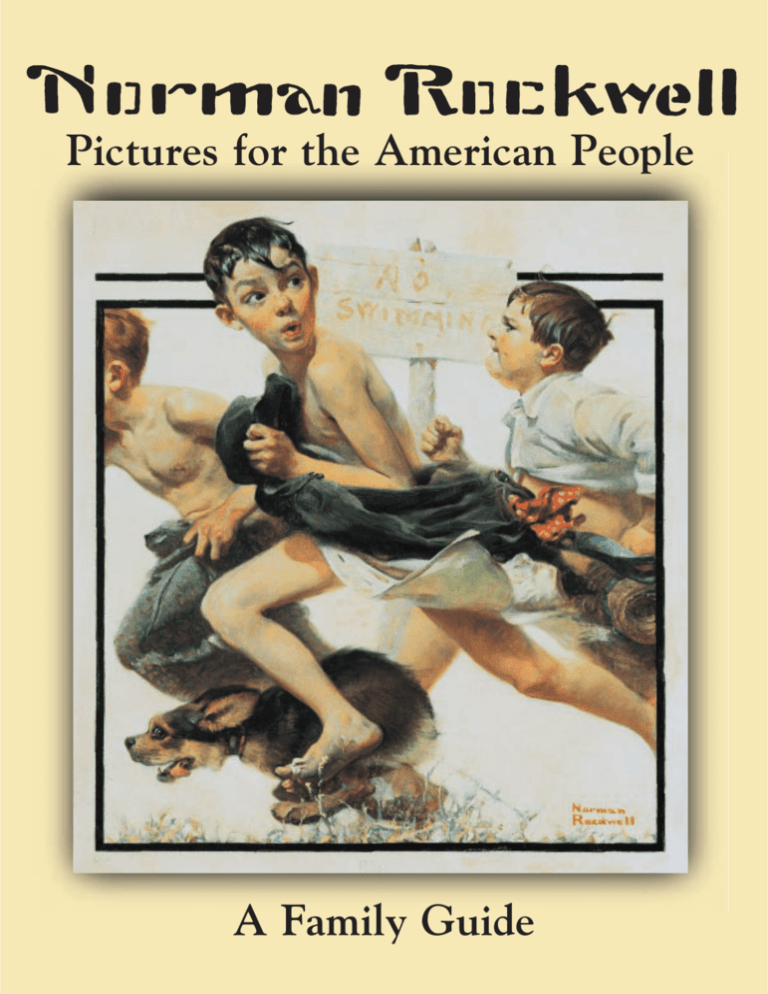

Are humorous:

Look at No Swimming on the

cover of this guide. Rockwell often paints the funniest

moment in a story. Rather than picture the boys

swimming in the forbidden pool, Rockwell paints the

moment when the rascals have been discovered and are

frantically trying to put their clothes back on as they

race from the scene of the crime.

Celebrate ordinary, everyday life:

Rockwell’s stories about swimming holes, gossiping,

family vacations, and barbershops are not what you read

about in newspaper headlines and history textbooks.

Rockwell painted scenes from the daily life of ordinary

people.

Are skillfully painted:

Rockwell carefully

studied the works of great artists like those pictured in

the upper right corner of the easel in Triple SelfPortrait. He also spent weeks, even months creating his

paintings.

LOOK

Look closely at the painting Triple

Self-Portrait. Can you find these items?

See page 15 for answers.

•

•

•

•

Rockwell often

included an image

of himself in his

paintings. Look for a

“Find Norman” symbol in

this family guide. When you see it,

search the painting for Rockwell’s

face. Remember sometimes he is

only a face in the crowd.

2

The “antique” that fooled Rockwell

The soft drink he often enjoyed as he worked

A reference to the accidental burning of his studio

A tribute to the great artists he admired

Triple Self-Portrait, 1960

The Saturday Evening Post

© 1960 The Curtis Publishing

Company

Many artists paint

pictures of themselves,

known as self-portraits.

When Rockwell painted

this self-portrait, he

included images of some

of his favorite artists

and shared details

about his life.

“It is no exaggeration to say simply that Norman

Rockwell is the most popular, the most loved, of all

contemporary artists...[H]e himself is like

a gallery of Rockwell paintings–friendly, human,

deeply American, varied in mood, but full,

always, of the zest of living.”

–Ben Hibbs, Saturday Evening Post Editor

TRY IT

Pretend you made a

visit to Rockwell’s studio. You two

hit it off quite well, and Rockwell

told you that, as a gift, he would like

you to select any item from this

painting. What would you bring

home and why? Draw a portrait of

yourself with your new treasure.

3

Rockwell The Artist

FUN FACT

Did you know

Rockwell left actual

globs of paint on

this canvas? Look

closely at the critic’s

palette. Each color

is a dried clump of

paint!

Art Critic, 1955, The Saturday Evening Post, © 1955 The Curtis Publishing Company

LOOK

Here is a finished painting entitled Art Critic. To the right is an early sketch.

How many differences can you find between the two versions? Can you think of any

reasons why Rockwell changed what he did?

4

Look more closely at some of Rockwell’s techniques.

Rockwell didn’t just sit down and begin to paint. Each painting was carefully

planned, and many took several months to complete.

• When he had an idea for a painting, Rockwell often took photographs of

models (sometimes his friends and neighbors) in various poses. A photo he

used to create Art Critic is shown at the right.

• He then mixed and matched details from these photos and made numerous

pencil sketches, rearranging the composition and adding new details.

• Rockwell sometimes coated the back of his final sketch with charcoal dust

and laid it on top of a canvas. By tracing the top image, he left a dust outline

on the canvas.

• He then painted on top of this sketchy image with oil paints, which covered

up the charcoal lines. Even while he was painting the picture, Rockwell often

made changes in the poses, the backgrounds, and facial expressions.

Photo by Gene Pelham

Photo by Bill Scovill

FUN FACT

The painting of the

woman in Art Critic

was based on photographs of Rockwell’s

wife, Mary.

5

Art Critic (study), 1955, © The Curtis Publishing Company

Rockwell The Humorist

6

The paintings on these two pages are called

sequence paintings because they are

composed of lots of little images that are

combined to tell a story, just like a comic

strip or a movie. The painting above is

entitled Day in the Life of a Little Girl.

Rockwell created another sequence painting

entitled Day in the Life of a Little Boy. Look

closely at this little girl’s day and try to

imagine what the boy’s day might look like.

Day in the Life of a Little Girl, 1952, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1952 The Curtis Publishing Company

TRY IT

Find a partner. Choose one of the images on

this page but don’t tell your partner which you chose. Simply

imitate the action and invite your partner to guess. Switch

and then guess as your partner imitates one of the images.

Remember, if you were a model for Norman Rockwell, you

might have to hold that pose for several minutes!

SEARCH

The people who posed for The Gossips were Rockwell’s neighbors in

Arlington, Vermont. His wife, Mary, appears in the painting, too. Look at her photograph on page 5 (posing for the painting Art Critic), then see if you can find her in the

painting below. The answer is on page 15. The models never knew how they would

look in the finished painting.

FUN FACT

The editor at The

Saturday Evening Post

did not believe that

anyone could have a

mouth as big as the

man with the black

hat. He said that no

one in America

would believe it.

Rockwell sent him a

photo of this man

with his mouth open,

and the editor had to

agree–that man had

one enormous mouth!

So the painting was

published exactly how

Rockwell painted it.

The Gossips, 1948, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1948 The Curtis Publishing Company

TRY IT

Write dialogue for the people in the

painting. Why is the woman at the end shocked?

Do you think the story the woman tells in the

beginning has changed by the end?

Why are some of the folks laughing?

7

Inventing America

America went through many changes during Rockwell’s sixty-year career. He often

illustrated these transitions from an old way of life to a new future by combining

something traditional with something modern. Today, these paintings help us imagine

what it must have been like to live in earlier times.

In the painting Going

and Coming, Rockwell

shows an old-fashioned

tradition: family gatherings. This family,

however, is wrapped in

a modern invention:

the American station

wagon.

LOOK

Notice

the feelings Rockwell

shows in the top part

of the painting. How

are the two parts the

same, how are they

different? Look for the

one person who

remains unchanged.

Going and Coming, 1947

The Saturday Evening Post

© 1947 The Curtis Publishing Company

During the 1940s and 1950s, a

feeling of hopeful idealism could

be found in a number of movies

and television shows, such as It’s

a Wonderful Life or Leave It To

Beaver. Like many Rockwell

paintings, these shows depicted

life in an idealized American

home.

8

• Can you think of a TV show or movie about average

people doing ordinary things in a small town?

• If you were to write a story or make a movie, would

it resemble your own life, or would it be a fantasy of

your imagining?

• Can you think of any changes that have taken place

in our world since your parents were your age?

FUN FACT

Rockwell said if he

were to paint this

work again, he

would leave out

the magazine.

How would this

change the

meaning of the

painting?

Girl at Mirror, 1954

The Saturday Evening Post

© 1954 The Curtis Publishing

Company

Rockwell remembers thinking about growing up when he was a child. He was a bit concerned about

not always fitting in with the other kids, “When I got to be ten or eleven…I could see I wasn’t God’s

gift to man in general or to the baseball coach in particular….At the age boys who are athletes were

expressing themselves fully….I didn’t have that. All I had was my ability to draw.”

LOOK

This painting captures a change from an old way of life

to a new way. See how the girl is in a room surrounded with oldfashioned things–her doll, the chair, her clothing. They all relate to

the past. She is looking in a mirror thinking about growing up,

and the comfortable old things around her may be Rockwell’s way

of suggesting that the old-fashioned values and traditions of the

past will help her as she moves into the future.

SEARCH

The little girl in this

painting is Mary Whalen Leonard, who

Rockwell met at a basketball game.

Rockwell often used her as a model

because he found she could act out “any

story.” Look through the family guide to

find another painting in which you can

find her acting out several stories.

9

Honoring the

American Spirit

When the United States entered World War II in

December 1941, Rockwell wanted to help in the war

effort. Remembering a speech President Franklin D.

Roosevelt had made earlier in the year, Rockwell

painted pictures to help people better understand the

four basic freedoms the president thought everyone in

the world should have: freedom of speech, freedom to

worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.

It took Rockwell seven months to complete the four

paintings. He painted Freedom of Speech and Freedom

to Worship several times before he was satisfied with

the results. In the middle of the night when pondering how to best depict freedom of speech, Rockwell

was struck with what he called “the best idea I’d ever

had.” He remembered a man who stood up at a town

meeting and made a comment. Everyone disagreed

with him but believed that he had the right to speak

his mind. This, Rockwell thought, was what freedom

of speech was all about.

Freedom of Speech, 1943, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1943 The Curtis Publishing Company

FUN FACT

Rockwell claimed

that the turkey featured in Freedom

from Want was, in fact, the Rockwell

family’s Thanksgiving turkey. He later

confessed, “This was one

of the few times I’ve

ever eaten the

model.”

SEARCH

Rockwell used many of his friends

and family in this painting. The woman serving the

Thanksgiving turkey in Freedom from Want was the

Rockwell family cook, and he also included his wife,

Mary. Look closely to find her.

10

Freedom from Want, 1943, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1943 The Curtis Publishing Company

SEARCH

The father in Freedom from Fear

appears in all four paintings. Can you find him?

FUN FACT

The American people

responded enthusiastically to

The Four Freedoms. After the

paintings appeared in The

Saturday Evening Post, 70,000

people wrote letters of praise

to the magazine. That’s a

stack of letters over six

basketball goals high!

Freedom from Fear, 1943

The Saturday Evening Post

© 1943 The Curtis Publishing Company

LOOK

Rockwell was able to

convey complicated ideas without

using words. By looking at the

details of a painting–the clothing

people wear, the expressions on their

faces–we discover things about them

that would take pages of text to

explain.

TRY IT

Pick a person from

one of The Four Freedoms and

describe everything you can about

his or her life just by the details

Rockwell has painted.

SEARCH

The woman with

a braid in her hair in Freedom to

Worship also appears in another

painting in this guide. Can you find

her?

Freedom to Worship, 1943, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1943 The Curtis Publishing Company

11

Honoring the

American Spirit

“Like everyone else, I'm concerned with the world

situation, and like everyone else, I'd like to

contribute something to help.”

–Norman Rockwell

Throughout his life,

Rockwell was concerned

with political issues, such

as racism, poverty, and

social injustice. In the

1960s, Rockwell painted

for Look magazine. These

illustrations addressed

important events of the

day and were generally

less humorous than those

he painted for The

Saturday Evening Post.

FUN FACT

During his life,

Rockwell traveled to

many countries in

Europe, as well as

India, Egypt, Iran,

and Turkey.

LOOK

Rockwell used photos of his friends

and neighbors in Vermont and Massachusetts

to compose the painting Golden Rule. What

similarities do you see between these individuals? Notice he shows two different women

holding babies. Why do you think he put two

people in almost the same pose at the center of

the painting?

12

Golden Rule, 1961, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1961 The Curtis Publishing Company

When Rockwell painted New Kids in the

Neighborhood, America was experiencing the

civil rights movement. Families from different

cultures and backgrounds were beginning to

live in the same neighborhoods, eat at the same

restaurants, and sit next to each other on buses.

New Kids in the Neighborhood, 1967, Look

© 1967 The Norman Rockwell

Estate Licensing Company

LOOK

The two groups of children in New

Kids in the Neighborhood may look different, but

they also have several things in common. Can

you find them? When the kids start to talk and

play together, what do you think they will find?

13

Celebrating the

Commonplace

“Commonplaces are never tiresome.

It is we who become tired when we cease to be curious

or appreciative...[We] find that it is not a new scene

which is needed, but a new viewpoint.”

–Norman Rockwell

Rockwell liked to focus

on the lives of ordinary

people in typical

American towns,

enjoying the simple

pleasures of life.

These images proved

very popular with

Saturday Evening Post

readers. They felt that

they were seeing

themselves on the

cover of a magazine!

TRY IT

In this painting,

Rockwell carefully created a

composition out of rectangles.

With a dark marker, outline the

rectangles you can see. Notice

how Rockwell built his painting

around these shapes.

Shuffleton’s Barbershop, 1950

The Saturday Evening Post

© 1950 The Curtis Publishing Company

LOOK

When looking at the painting Shuffleton’s Barbershop, what

is your viewpoint? Where are you standing as you look in on this scene?

What kinds of clues can you find about the shop?

Who might work there? What other hobbies do they have?

Who are the people inside, and how long have they known each other?

Can you think of a tune they might be playing? What other

instruments might be in the group hidden from our view?

14

Rockwell gives us lots of clues to help us understand the story he’s

telling. Sometimes he leaves things hidden so we can imagine

stories of our own.

Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People

is organized by The Norman Rockwell Museum at Stockbridge

and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

The exhibition and its national tour are made possible by Ford Motor Company.

The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are also made possible by The Henry Luce Foundation.

Additional support is provided by The Curtis Publishing Company and

The Norman Rockwell Estate Licensing Company.

Education programs for the national tour are made possible by

Fidelity Investments through the Fidelity Foundation.

In Atlanta, the exhibition is made possible by The Fraser-Parker Foundation.

No Swimming, 1921, The Saturday Evening Post

© 1921 The Curtis Publishing Company

Page 7 Mary is the second person from the left

in the third row.

The pictures pinned to

Rockwell’s canvas are selfportraits by Albrecht

Dürer, Rembrandt, Pablo

Picasso, and Vincent van

Gogh.

ON THE COVER

WORD SEARCH

self-portrait

Norman

Rockwell

sequence

traditional

modern

magazine

golden rule

T

R

E

D

B

E

C

N

E

U

Q

E

S

D

N

S

M

O

D

E

E

R

F

E

G

P

H

L

A

C

I

T

I

L

O

P

I

E

D

E

A

R

O

T

A

R

T

S

U

L

L

I

N

O

P

M

T

E

R

B

P

E

L

S

H

R

I

I

O

H

U

M

O

R

O

U

S

O

freedoms

photograph

models

American

E

T

H

N

A

M

R

O

N

H

R

E

T

D

I

S

P

W

T

E

P

A

I

N

T

O

O

D

O

L

R

A

I

C

I

L

E

C

G

political

illustrator

humorous

commonplace

M

A

G

A

Z

I

N

E

T

R

D

H

R

E

R

I

C

H

A

M

O

D

E

L

S

A

E

T

H

E

L

L

E

W

K

C

O

R

P

D

E

A

M

E

R

I

C

A

N

G

Y

H

15

Page 11 Rose Hoyt also

appears in Golden Rule.

Page 10 (Find Norman)

Only a portion of

Rockwell’s face can be

seen. His eye is visible

on the left edge of the

painting, looking at the

man speaking.

Page 10 Mary Rockwell

is sitting on the left of

the table, and Rockwell’s

mother is on the right.

The smoke rising from

the trash can is a reference to the accidental

burning of Rockwell’s studio in 1943.

Page 9 She also was the

model for Day in the Life

of a Little Girl on page 6.

Norman Rockwell’s daily

cola drink is precariously

perched on his art book.

Page 7 (Find Norman)

Rockwell appears in the

last row, pointing at the

woman. He was the

subject of the

gossip.

Page 2 The gold helmet

atop the easel: Rockwell

thought it was an antique

army helmet but later

discovered it was just a

fireman’s hat!

ANSWERS

TRY IT

Make your own Saturday Evening Post cover using Rockwell’s technique (see pages

4-5 for ideas). Think of something you want to celebrate about your life, your town, or your

neighborhood. Sketch all the different ideas you have, then select the very best one. Using a

sharp pencil, lightly trace the outlines of the image in the box provided. Add more details by

tracing from different images. When you are finished, use crayons or paint to color in the image.

Resources Menu | Coffee | Library | Gallery | Lucidcafé Home | Revised: January 1, 2011

Norman Rockwell

American Illustrator and Painter

1894 - 1978

I showed the America I knew and observed

to others who might not have noticed.

—Norman Rockwell

Norman Percevel Rockwell was born on February 3, 1894, the second son of Nancy and Waring Rockwell. He and his brother Jarvis lived in

New York City until Norman was 9 years old at which point they moved to the suburban commuter town of Mamaroneck. Norman left high

school early to return to New York City, settling at the Arts Student League to study art where his discipline, hard work, and sense of humor

were widely recognized. As a student Norman was given small illustration jobs, but his major breakthrough came in 1912 with his first book

illustration for C.H. Claudy's Tell Me Why: Stories about Mother Nature. By 1913 he was art editor for Boy's Life and just 19 years old.

Considered a modest, retiring man, not given to grand gestures, Norman impressed himself on America's collective imagination by his stubborn

adherence to the old values. His ability to relate these values to the events and circumstances of a rapidly changing world made him a special

person—both hero and friend—to millions of his compatriots.

It has often been said that Norman provided a commodity that people could rely on. This is clearly reflected in more than 4,000 illustrations

completed throughout his 47 year career. He is best known for his contributions to the Saturday Evening Post for whom he produced 332

covers, beginning in 1916. It is noteworthy that the Post could automatically increase its print order by 250,000 copies when an issue had a

cover by Rockwell.

Eighty magazines used his cover illustrations but, by far, no paintings by an American were ever published on such a global scale as Rockwell's

"Four Freedoms." First appearing in the Post, the originals were used by the United States Treasury in a 16 city tour seen by 1,222,000 people

who purchased over $133,000,000 in war bonds.

Norman's ability to "get the point across" in one picture, and his flair for painstaking detail made him a favorite of the advertising industry. He

was also commissioned to illustrate over 40 books including the ever popular Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. His annual

contributions for the Boy Scout calendars (1925 - 1976), was only slightly overshadowed by his most popular of calendar works - the "Four

Seasons" illustrations for Brown & Bigelow were published for 17 years beginning in 1947 and reproduced in various styles and sizes since

1964. Illustrations for booklets, catalogs, posters (particularly movie promotions), sheet music, stamps, playing cards, and murals (including

Yankee Doodle Dandy, was completed in 1936 for the Nassau Inn in Princeton, New Jersey) rounded out Rockwell's oeuvre as an illustrator. In

his later years, Rockwell began receiving more attention as a painter when he chose more serious subjects such as the series on racism for

Look magazine.

Christopher Finch, author and art curator, had this to say: "Norman Rockwell created a world that, because of its traditional elements, seems

familiar to all of us, yet is recognizably his and his alone. He is an American original who left his mark not by effecting radical change but rather

by giving old subjects his own, inimitable inflection. His career has been an ode to the ordinary, a triumph of common sense and

understatement."

Rockwell made no secret of his lifetime preference for countrified realism . . . "Things happen in the country, but you don't see them. In the city

you are constantly confronted by unpleasantness. I find it sordid and unsettling." His time spent in the country was a great influence on his

idyllic approach to storytelling on canvas. From 1953 until his death in 1978, Norman lived at Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where there is a

museum devoted to him.

Although Norman Rockwell was always at odds with contemporary notions of what an artist should be, he chose to paint life as he wanted to

see it. His themes and unique style have passed the test of time making him the best known of all American artists.

If you are aware of any Internet resources, films or books about Norman Rockwell or related subjects, or if you would like to submit comments,

please send us email: rc@lucidcafe.com.

Resources

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Norman Percevel Rockwell (February 3, 1894 – November 8, 1978)

was a 20th-century American painter and illustrator. His works enjoy a

broad popular appeal in the United States, where Rockwell is most

famous for the cover illustrations of everyday life scenarios he created

for The Saturday Evening Post magazine for more than four decades.[1]

Among the best-known of Rockwell's works are the Willie Gillis series,

Rosie the Riveter (although his Rosie was reproduced less than others of

the day), Saying Grace (1951), The Problem We All Live With, and the

Four Freedoms series. He is also noted for his work for the Boy Scouts

of America (BSA); producing covers for their publication Boys' Life,

calendars, and other illustrations.

1 Life and works

1.1 Early life

1.2 World War I

1.3 Personal life

1.4 World War II

1.5 Later career

2 Body of work

2.1 Influence

3 List of major works

4 Gallery

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Norman Rockwell

Birth name

Norman Percevel Rockwell

Born

February 3, 1894

New York City, New York

Died

November 8, 1978 (aged 84)

Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Nationality

United States

Field

Painting, illustrator

Training

National Academy of Design

Art Students League

Works

Willie Gillis

Saying Grace

Four Freedoms

Early life

Norman Rockwell was born on February 3, 1894, in New York City to Jarvis Waring Rockwell and Anne Mary "Nancy"

(née Hill) Rockwell.[2][3][4] His earliest American ancestor was John Rockwell (1588–1662), from Somerset, England, who

immigrated to America probably in 1635 aboard the ship Hopewell and became one of the first settlers of Windsor,

Connecticut.[5] He had one brother, Jarvis Waring Rockwell, Jr., older by a year and half.[6][7] Jarvis Waring, Sr., was the

manager of the New York office of a Philadelphia textile firm, George Wood, Sons & Company, where he spent his entire

career.[6][8][9]

Norman transferred from high school to the Chase Art School at the age of 14. He then went on to the National Academy

of Design and finally to the Art Students League. There, he was taught by Thomas Fogarty, George Bridgman, and Frank

Vincent DuMond; his early works were produced for St. Nicholas Magazine, the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) publication

Boys' Life and other juvenile publications. Joseph Csatari carried on his legacy and style for the BSA.

As a student, Rockwell was given smaller, less important jobs. His first major breakthrough came in 1912 at age eighteen

with his first book illustration for Carl Harry Claudy's Tell Me Why: Stories about Mother Nature.

In 1913, the nineteen-year old Rockwell became the art editor for Boys' Life, published by the Boy Scouts of America, a

post he held for three years (1913–1916).[10] As part of that position, he painted several covers, beginning with his first

published magazine cover, Scout at Ship's Wheel, appearing on the Boys' Life September 1913 edition.

World War I

During the First World War, he tried to enlist into the U.S. Navy but was refused entry

because, at 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and 140 pounds (64 kg), he was eight pounds underweight.

To compensate, he spent one night gorging himself on bananas, liquids and doughnuts, and

weighed enough to enlist the next day. However, he was given the role of a military artist

and did not see any action during his tour of duty.

Rockwell's family moved to New Rochelle, New York when

Norman was 21 years old and shared a studio with the

cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, who worked for The Saturday

Evening Post. With Forsythe's help, he submitted his first

successful cover painting to the Post in 1916, Mother's Day

Off

(published on May 20). He followed that success with

Scout at Ship's Wheel, 1913

Circus Barker and Strongman (published on June 3), Gramps

at the Plate (August 5), Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins

(September 16), People in a Theatre Balcony (October 14) and Man Playing Santa

(December 9). Rockwell was published eight times total on the Post cover within the first

twelve months. Norman Rockwell published a total of 322 original covers for The Saturday

Evening Post over 47 years. His Sharp Harmony appeared on the cover of the issue dated

September 26, 1936; depicts a barber and three clients, enjoying an a cappella song. The image

was adopted by SPEBSQSA in its promotion of the art.

The Four

Freedoms:Freedom of

Speech

Rockwell's success on the cover of the Post led to covers for other magazines of the day, most

notably The Literary Digest, The Country Gentleman, Leslie's Weekly, Judge, Peoples

Popular Monthly and Life Magazine.

Personal life

Rockwell married his first wife, Irene O'Connor, in 1916. Irene was Rockwell's model in

Mother Tucking Children into Bed, published on the cover of The Literary Digest on January

19, 1921. However, the couple were divorced in 1930. Depressed, he moved briefly to

Alhambra, California as a guest of his old friend Clyde Forsythe. There he painted some of his

best-known paintings including "The Doctor and the Doll". While there he met and married

schoolteacher Mary Barstow.[11] The couple returned to New York shortly after their marriage.

They had three children: Jarvis Waring, Thomas Rhodes and Peter Barstow. The family lived at

24 Lord Kitchener Road in the Bonnie Crest neighborhood of New Rochelle, New York.

Rockwell and his wife were not very religious, although they were members of St. John's

Wilmot Church, an Episcopal church near their home, and had their sons baptized there as

well. Rockwell moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939 where his work began to reflect

small-town life.[citation needed]

The Four

Freedoms:Freedom from

Want

In 1953, the Rockwell family moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, so that his wife could be treated at the Austen Riggs

Center, a psychiatric hospital at 25 Main Street, down Main Street from where Rockwell set up his studio.[12] Rockwell

himself received psychiatric treatment from the renowned analyst Erik Erikson, who was on staff at Riggs. Erikson is said

to have told the artist that he painted his happiness, but did not live it.[13] In 1959, Mary Barstow Rockwell died

unexpectedly of a heart attack. In 1961, Rockwell married Molly Punderson, a retired teacher.

World War II

The rear of Norman Rockwell's

preserved studio.

In 1943, during the Second World War, Rockwell painted the Four Freedoms series,

which was completed in seven months and resulted in his losing 15 pounds. The

series was inspired by a speech (http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches

/fdrthefourfreedoms.htm) by Franklin D. Roosevelt, in which he described four

principles for universal rights: Freedom from Want, Freedom of Speech, Freedom to

Worship, and Freedom from Fear. The paintings were published in 1943 by The

Saturday Evening Post. The United States Department of the Treasury later

promoted war bonds by exhibiting the originals in 16 cities. Rockwell himself

considered "Freedom of Speech" to be the best of the four. That same year a fire in

his studio destroyed numerous original paintings, costumes, and props.

Shortly after the war, Rockwell was contacted by writer Elliott Caplin, brother of

cartoonist Al Capp, with the suggestion that the three of them should make a daily

comic strip together, with Caplin and his brother writing and Rockwell drawing. King Features Syndicate is reported to

have promised a $1,000/week deal, knowing that a Capp-Rockwell collaboration would gain strong public interest.

However, the project was ultimately aborted as it turned out that Rockwell, known for his perfectionism as an artist, could

not deliver material as fast as required of him for a daily comic strip.[14]

During the late 1940s, Norman Rockwell spent the winter months as artist-in-residence at Otis College of Art and Design.

Students occasionally were models for his Saturday Evening Post covers. In 1949, Rockwell donated an original Post cover,

"April Fool," to be raffled off in a library fund raiser.

In 1959, his wife Mary died unexpectedly, and Rockwell took time off from his work to grieve. It was during this break that

he and his son Thomas produced his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, which was published in 1960. The

Post printed excerpts from this book in eight consecutive issues, the first containing Rockwell's famous Triple

Self-Portrait.

Later career

Rockwell married his third wife, retired Milton Academy English teacher, Molly Punderson,

in 1961. His last painting for the Post was published in 1963, marking the end of a

publishing relationship that had included 322 cover paintings. He spent the next 10 years

painting for Look magazine, where his work depicted his interests in civil rights, poverty and

space exploration. In 1968 Rockwell was commissioned to do an album cover portrait of

Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper for their record, The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield

and Al Kooper.[15] During his long career, he was commissioned to paint the portraits for

Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, as well as those of foreign figures,

including Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru. One of his last works was a portrait of

Judy Garland in 1969.

A custodianship of his original paintings and drawings was established with Rockwell's help

Norman Rockwell

near his home in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and the Norman Rockwell Museum is still

open today year round. Norman Rockwell Museum is the authoritative source for all things

Norman Rockwell. The Museum's collection is the world's largest, including more than 700 original Rockwell paintings,

drawings, and studies. The Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies at the Norman Rockwell Museum is a national

research institute dedicated to American illustration art.

When he was concerned with his health he placed his studio and the contents with the Norman Rockwell Museum, which

was formerly known as the Stockbridge Historical society and even more formerly known as the Old Corner house, in a

trust.

For "vivid and affectionate portraits of our country," Rockwell received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United

States of America's highest civilian honor, in 1977.

Rockwell died November 8, 1978 of emphysema at age 84 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. First Lady Rosalynn Carter

attended his funeral.

Norman Rockwell was a prolific artist, producing over 4,000 original works in his lifetime.

Most of his works are either in public collections, or have been destroyed in fire or other

misfortunes. Rockwell was also commissioned to illustrate over 40 books including Tom

Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. His annual contributions for the Boy Scouts' calendars

between 1925 and 1976 (Rockwell was a 1939 recipient of the Silver Buffalo Award, the

highest adult award given by the Boy Scouts of America[16]), were only slightly

overshadowed by his most popular of calendar works: the "Four Seasons" illustrations for

Brown & Bigelow that were published for 17 years beginning in 1947 and reproduced in

various styles and sizes since 1964. Illustrations for booklets, catalogs, posters (particularly

movie promotions), sheet music, stamps, playing cards, and murals (including "Yankee

Doodle Dandy" and "God Bless the Hills", which was completed in 1936 for the Nassau Inn

in Princeton, New Jersey) rounded out Rockwell's œuvre as an illustrator.

His first Scouting calendar

(1925)

In 1969, as a tribute to Rockwell's 75th year birthday,

officials of Brown & Bigelow and the Boy Scouts of

America asked Rockwell to pose in Beyond the Easel,

the calendar illustration that year.[17]

Rockwell's work was dismissed by serious art critics in his lifetime.[18] Many of his

works appear overly sweet in modern critics' eyes,[19] especially the Saturday Evening

The Problem We All Live With

Post covers, which tend toward idealistic or sentimentalized portrayals of American

life— this has led to the often-deprecatory adjective "Rockwellesque." Consequently,

Rockwell is not considered a "serious painter" by some contemporary artists, who often regard his work as bourgeois and

kitsch. Writer Vladimir Nabokov sneered that Rockwell's brilliant technique was put to "banal" use, and wrote in his book

Pnin: "That Dalí is really Norman Rockwell's twin brother kidnapped by Gypsies in babyhood". He is called an "illustrator"

instead of an artist by some critics, a designation he did not mind, as it was what he called himself.[20]

However, in his later years, Rockwell began receiving more attention as a painter when he

chose more serious subjects such as the series on racism for Look magazine.[21] One

example of this more serious work is The Problem We All Live With, which dealt with the

issue of school racial integration. The painting depicts a young African American girl, Ruby

Bridges, flanked by white federal marshals, walking to school past a wall defaced by racist

graffiti.[22]

In 1999, The New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl said of Rockwell in ArtNews: “Rockwell

is terrific. It’s become too tedious to pretend he isn’t.”[18]

Beyond the Easel, 1969

calendar

Rockwell's work was exhibited at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2001.[23]

Rockwell's Breaking Home Ties sold for $15.4 million at a 2006 Sotheby’s auction.[18] A

twelve-city U.S. tour of Rockwell's works took place in 2008.[10]

Influence

In the film Empire of the Sun, a young boy (played by Christian Bale), is put to bed by his loving parents in a

scene also inspired by a Rockwell painting—a reproduction of which is

later kept by the young boy during his captivity in a prison camp.

(Freedom from Fear, 1943).[24]

The 1994 film Forrest Gump includes a shot in a school that re-creates

Rockwell's "Girl with Black Eye" with young Forrest in place of the girl.

Much of the film drew heavy visual inspiration from Rockwell's art.[25]

Film director George Lucas owns Rockwell's original of The Peach Crop,

and his colleague Steven Spielberg owns a sketch of Rockwell's Triple

Self-Portrait. Each of the artworks hangs in the respective filmmakers'

workspaces.[18] Rockwell is a major character in an episode of Lucas’

Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, “Passion for Life.”

In 2005, Target Co. sold Marshall Field's to Federated Department Stores

and the Federated discovered a reproduction of Rockwell's The Clock

Mender, which depicted the great clocks of the Marshall Field and

Company Building on display.[26][27] Rockwell had donated the painting

depicted on the cover of the November 3, 1945 Saturday Evening Post to

Cover of October 1920 issue of

the store in 1948.[28]

Popular Science magazine

On Norman Rockwell's birthday, February 3, 2010, Google featured

Rockwell's iconic image of young love "Boy and Girl Gazing at the

Moon" which is also known as "Puppy Love" on its home page. The

response was so great that day that the Norman Rockwell museum's servers went down under the onslaught.

[citation needed]

"Dreamland," a track from Canadian alternative rock band Our Lady Peace's 2009 album Burn Burn, was

inspired by Rockwell's paintings.[29]

Scout at Ship's Wheel (first published magazine cover illustration, Boys' Life, September 1913)

Santa and Scouts in Snow (1913)

Boy and Baby Carriage (1916; first Saturday Evening Post cover)

Circus Barker and Strongman (1916)

Gramps at the Plate (1916)

Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (1916)

People in a Theatre Balcony (1916)

Tain't You (1917; first Life magazine cover)

Cousin Reginald Goes to the Country (1917; first Country Gentleman cover)

Santa and Expense Book (1920)

Mother Tucking Children into Bed (1921; first wife Irene is the model)

No Swimming (1921)

Santa with Elves (1922)

Doctor and Doll (1929)

Deadline (1938)

The Four Freedoms (1943)

Freedom of Speech (1943)

Freedom to Worship (1943)

Freedom from Want (1943)

Freedom from Fear (1943)

Rosie the Riveter (1943) [2] (http://www.rosietheriveter.org/painting.htm)

Going and Coming (1947)

Bottom of the Sixth (or The Three Umpires; 1949)

Saying Grace (1951)

The Young Lady with the Shiner (1953)

Girl at Mirror (1954)

Breaking Home Ties (1954)[30]

The Marriage License (1955)

The Scoutmaster (1956)[31]

The Runaway (1958)

Triple Self-Portrait (1960)

Golden Rule (1961)

The Problem We All Live With (1964)

Southern Justice (Murder in Mississippi) (1965) [3]

(http://www.artchive.com/artchive/R/rockwell/rockwell_mississippi.jpg.html)

New Kids in the Neighborhood (1967)

Russian Schoolroom (1967)

The Rookie

Spirit of 76 (1976) (stolen in 1978 but recovered in 2001 by the FBI's

Robert King Wittman)

The Rookie, one of many Saturday

Evening Post covers

The pictures of NORMAN ROCKWELL (1894-1978) were recognized and loved

by almost everybody in America. The cover of The Saturday Evening Post was his

showcase for over forty years, giving him an audience larger than that of any other

artist in history. Over the years he depicted there a unique collection of Americana,

a series of vignettes of remarkable warmth and humor. In addition, he painted a

great number of pictures for story illustrations, advertising campaigns, posters,

calendars, and books.

As his personal contribution during World War II, Rockwell painted the famous

"Four Freedoms" posters, symbolizing for millions the war aims as described by

President Franklin Roosevelt. One version of his "Freedom of Speech" painting is

in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rockwell left high school to attend classes at the National Academy of Design and

later studied under Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman at the Art Students

League in New York. His early illustrations were done for St. Nicholas magazine

and other juvenille publications. He sold his first cover painting to the Post in 1916

and ended up doing over 300 more. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson

sat for him for portraits, and he painted other world figures, including Nassar of

Egypt and Nehru of India.

In 1957 the United States Chamber of Commerce in Washington cited him as a

Great Living American, saying that..."Through the magic of your talent, the folks

next door - their gentle sorrows, their modest joys - have enriched our own lives

and given us new insight into our countrymen."

The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts has established a large collection of his paintings, and has preserved Rockwell's

last studio as well.

[Preliminary study for "Freedom of Speech", 1942.

This piece set an auction record at $407,000.]

- Norman Rockwell Museum - http://www.nrm.org -

About Norman Rockwell

Posted By admin On September 28, 2009 @ 11:33 am In | Comments Disabled

A Brief Biography

Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the

America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.

—Norman Rockwell

Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an

artist. At age 14, Rockwell enrolled in art classes at The New York School

of Art (formerly The Chase School of Art). Two years later, in 1910, he left

high school to study art at The National Academy of Design. He soon

transferred to The Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas

Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty’s instruction in illustration

prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman,

Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long

career.

Rockwell found success early. He painted his first commission of four

Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. While still in his teens, he

was hired as art director of Boys’ Life, the official publication of the Boy

Scouts of America, and began a successful freelance career illustrating a

variety of young people’s publications.

At age 21, Rockwell’s family moved to New Rochelle, New York, a community whose residents included such

famous illustrators as J.C. and Frank Leyendecker and Howard Chandler Christy. There, Rockwell set up a

studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe and produced work for such magazines as Life, Literary Digest, and

Country Gentleman. In 1916, the 22-year-old Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post,

the magazine considered by Rockwell to be the “greatest show window in America.” Over the next 47 years,

another 321 Rockwell covers would appear on the cover of the Post. Also in 1916, Rockwell married Irene

O’Connor; they divorced in 1930.

The 1930s and 1940s are generally considered to be the most fruitful

decades of Rockwell’s career. In 1930 he married Mary Barstow, a

schoolteacher, and the couple had three sons, Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter.

The family moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939, and Rockwell’s work

began to reflect small-town American life.

In 1943, inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s address to Congress,

Rockwell painted the Four Freedoms paintings. They were reproduced in

four consecutive issues of The Saturday Evening Post with essays by

contemporary writers. Rockwell’s interpretations of Freedom of Speech,

Freedom to Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear proved

to be enormously popular. The works toured the United States in an

exhibition that was jointly sponsored by the Post and the U.S. Treasury

Department and, through the sale of war bonds, raised more than $130

million for the war effort.

Although the Four Freedoms series was a great success, 1943 also brought

Rockwell an enormous loss. A fire destroyed his Arlington studio as well as

numerous paintings and his collection of historical costumes and props.

In 1953, the Rockwell family moved from Arlington, Vermont, to

Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Six years later, Mary Barstow Rockwell died

unexpectedly. In collaboration with his son Thomas, Rockwell published his autobiography, My Adventures as

an Illustrator, in 1960. The Saturday Evening Post carried excerpts from the best-selling book in eight

consecutive issues, with Rockwell’s Triple Self-Portrait on the cover of the first.

In 1961, Rockwell married Molly Punderson, a retired teacher. Two years later, he ended his 47-year

association with The Saturday Evening Post and began to work for Look magazine. During his 10-year

association with Look, Rockwell painted pictures illustrating some of his deepest concerns and interests,

including civil rights, America’s war on poverty, and the exploration of space.

In 1973, Rockwell established a trust to preserve his artistic legacy by placing his works in the custodianship of

the Old Corner House Stockbridge Historical Society, later to become Norman Rockwell Museum at

Stockbridge. The trust now forms the core of the Museum’s permanent collections. In 1976, in failing health,

Rockwell became concerned about the future of his studio. He arranged to have his studio and its contents

added to the trust. In 1977, Rockwell received the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of

Freedom.

In 2008, Rockwell was named the official state artist of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, thanks to a

dedicated effort from students in Berkshire County, where Rockwell lived for the last 25 years of his life.

Like

202 people like this. Be the first of your friends.

Article printed from Norman

Rockwell Museum: http://www.nrm.org

URL to article: http://www.nrm.org/about-2/about-norman-rockwell/

Copyright© 2009 Norman Rockwell Museum. All rights reserved.