Streetart

advertisement

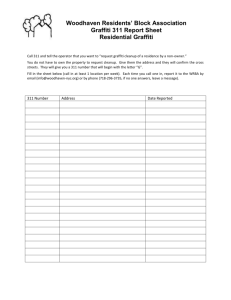

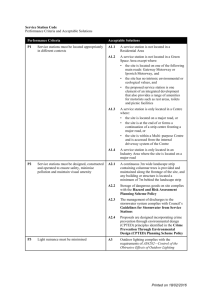

Explore innovative paths in architecture STREET ART Facades – moving with the times Dear readers, on this special form of artistic expression which has chosen the architectural surfaces of the urban envi- Is graffiti a form of artistic expression or pure vandal- ronment as its canvas. ism? Keith Haring would appear to have answered this question once and for all. Many a caretaker In the 1970s, this was undoubtedly a reaction against nevertheless seems to lack an appreciation of graf- what was seen as a bleak and hostile urban landscape fiti‘s artistic credentials – or an understanding of a and as such, a protest against the excesses of the young artists‘ motivation. Architects may also find it building industry. But what is the significance of difficult to welcome such unsolicited embellishments graffiti in 2011? As a precautionary measure, we at with open arms, especially when their own buildings RENOLIT have invented the RENOLIT EXOFOL FX film provide the “canvas“. to cope with any artistic mishaps. Artists who are not content with their graffiti can simply wipe it off this The graffiti adorning Alvaro Siza‘s apartment building film surface and replace it with a new work. which was erected at the time of the Berlin International Building Exhibition in 1984 has since acquired We hope you will enjoy reading this new issue legendary status. The building stood for a long time of Colour Road, the architecture magazine from with this protest art on its facade, etching itself into RENOLIT. the collective consciousness of the architectural world. The strict linearity in Siza‘s architecture proved more than a match for the Berlin sprayer‘s works. We nevertheless visited the Portuguese Pritzker award winner‘s office to find out what this graffiti meant to Yours, him at the time. You can read his answer in this issue Pierre Winant of Colour Road – along with various other features Board Member, RENOLIT SE in the areas where they lived in 1968. Following the first feature on a “writer”, who went by the name of Taki 183 in the New York Times in 1971, the movement took on undreamt of proportions. The “pieces” , as the letter-based works are known, became increasingly extravagant in order to set them apart from the rest of the graffiti on offer. The movement also spread to Europe. In Paris, stencils and posters were used to communicate political views. Graffiti art entered a new dimension with Keith Haring in New York and Blek le Rat in Paris in the 1980s, followed a little later by Banksy in London. Around the time of the millennium it experienced a veritable boom, due in part to developments in media. As in the beginning, the artists continued to act unlawfully, autonomously and outside of the art establishment. The works were public and accessible to everyone, turning the urban environment into a gallery. Long gone were the days when graffiti artists restricted themselves to a single work. Walking through London, Banksy‘s rat stencils are in evidence throughout the city, as are Blek le Rat‘s rodents in Paris. They create their own narrative as they “run” through the city. In Berlin it is Kripoe‘s yellow fists, and in Granada the moving pictures of “El niño de las pinturas” (“The child of the paintings”) that appear on walls telling their own stories. In Granada, the pictures have even been compiled into a catalogue and while travel agencies offer graffiti sightseeing trips, the municipal authorities have fined the artist for vandalism and damage to property! Despite these examples of graffiti enriching the urban environment, it remains illegal to spray graffiti – which is clearly part of the thrill for the artists involved. Most graffiti is painted over very soon after it has been produced, and many works have very short lives. This ensures that this form of personal expression is always highly topical and developing at a fast pace akin to the breakneck speed of “streetlife”. Photo: ©Giuliano Maciocci Fotolia.com Ever since ancient times, the street has been seen as an urban space for communication and public debate. Until the invention of radio and television, public places were where news was spread and the latest information exchanged. Today, the presence of masses on the streets is still understood to be a proclamation of dissatisfaction, protest and resistance – indeed, such mass gatherings now have an even greater impact than in former times due to their rarity. While the urban environment remains a stage for protests – as this spring has shown – its significance as a venue for ongoing debate and communication has diminished. The emergence of the automobile as a mass-produced phenomenon in the 20th century brought great changes to the way pubic space was used. The street increasingly became a place of fast-paced movement in specific directions. The pleasant little alleys and squares of old established towns gave way to wide carriageways and the streets became noisy with increasing flows of traffic. Since the 1960s, various events in the art scene drew attention to this phenomenon of the dehumanisation of public space, examples being the actions by the Situation ists in the 1960s and the “Reclaim the Streets” events in the 1990s. In cities throughout the world, artistic intervention in the urban environment has long become an integral part of daily life. Artists take direct action, for the most part anonymously and illegally and often as a mark of rebellion against long-established norms; whether it is against the art and museum establishment or against the transformation of architectural environments into commercial billboards. Graffiti (from the Italian “graffito”, plural “graffiti” – an inscription scratched in stone) was the main springboard of street art, and remains its best known form today . It covers a broad spectrum, from lettering through stencils and murals to the more recent light graffiti. Young New Yorkers began writing their names on exposed surfaces Banksy B r i t i s h S p ra y e r B a n k s y i s a rg u a b l y t h e b e s t - k n o w n s t re e t a r t i s t a ro u n d – d e s p i t e h i s g re a t e f f o r t s t o c o n c e a l h i s i d e n t i t y. H e h a s b e e n a c t i v e t h ro u g h o u t t h e w o r l d s i n c e t h e 1 9 9 0 s. A s w e l l a s i n E u ro p e , h i s w o rks can be fo und i n A ust ral i a, Israel , Cu b a, M ex i c o and Mali. His works also make regular appearances in m us e um s, in s o m e in st an c es h avi ng b een hung t h ere b y t h e ar t i st h i m sel f ! Wi t h a d r y sense o f hum o u r, h e c r i t i c i ses so c i et y an d p o l i t i c s, as w el l as h u m an t rai t s suc h as g reed , h yp o c r i sy and c o n su m er i sm . A l t h o u g h hi s w o r k s are f req uent l y c o nd em n ed as vand al i sm , he has achieved worldwide fame and at an auction in New Yo r k i n 2 0 0 8 , o n e o f h i s w o r k s reac h ed t h e o n e m i l l i o n d o l l ar m ar k ! ISSUE | 02 Explore innovative paths in architecture Bonjour Tristesse The Schlesisches Tor apartment building was completed in Berlin Kreuzberg as part of the 1984 International Building Exhibition, built to plans by Alvaro Siza. On completion, the corner building featuring a sleek, sweeping facade attracted the attentions of a sprayer, who duly applied the message “Bonjour Tristesse” around the eye-shaped opening on the gable. Alvaro Siza‘s initial response was to have the area painted over but as the plaster was integrally coloured, this was not possible. Replacing the plaster only at this spot would have given it more prominence, and replastering the entire building was financially unviable. The architect therefore had no choice but to leave it as it was. The romantic idea circulating in some trade media at the time that Siza had commissioned the graffiti himself is untrue. Irrespective of the quality of the pictures, the architect is not especially fond of graffiti, comparing it to paintings being hung in one‘s own house against one‘s will! Foto: Georg Slickers/Wikimedia Commons ISSUE | 02 Explore innovative paths in architecture Seres Queridos The international project “Seres Queridos/Etres Aimes” (Loved Ones) began in 2010 in Monterrey, Mexico. The original idea came from ARTO - Art Beyond Museums (Mexico) and Nobulo, a Spanish organisation which seeks to forge links between different Communities through artistic and cultural projects. Starting from the premise that a city gets its appeal not only from its architecture and history, but also from its people; with the aid of the municipal authorities they invited the local residents to choose characters of their liking. The unsung heroes, the likes of whom we encounter every day (from the car park attendant in the old quarter to the bookshop owner who has been selling second-hand books in the street for years). Portraits of these people were then produced by a group of internationally recognised graffiti artists. Not for a museum, but for the city itself. Giant portraits of their faces now adorn large areas in the city centre which would otherwise have been used for large-format advertising posters. While an argument ensued about the difference between art and vandalism, the majority quickly accepted the new works of art. The project has continued in Campeche, Mexico and is currently in Paris. ISSUE | 02 Explore innovative paths in architecture Photos: NOBULO & ARTO Graffi Gr G raf affi fitti ti – love lovve it i or hate it: everyone must decide forr themselves w wh etth heer th hey w wi ish to see it on their own façade. Whi le some may whether they wish While turn tu urrn n out out too be b a work of art others are unsightly inscriptions. PPutting Pu tttin ing this th hiss decision ddec e ision into action needn’t be difficult cult nor costly! RENOLIT R RE ENO NOLLIIT ooffers ffer ff e s a solution: undesired embellishment er embellishments ts can be rem mo ove v d simply simpply ly and swiftly from surfaces finished with wiith RENOLIT moved EEX XXOF OFOL OF OL FX FX film. lm m. EXOFOL Photos: RENOLIT SE ISSUE | 02 Explore innovative paths in architecture Publisher‘s details RENOLIT SE Monika Fecht Horchheimer Str. 50 67547 Worms – Germany www.renolit.com www.renolit.com/colourroad Tel: +49 6241 303-377 Fax: +49 6241 38058 E-mail: cr@renolit.com Design and editing: GKT – Gesellschaft für Knowhow-Transfer in Architektur und Bauwesen mbH Leinfelden-Echterdingen – Germany