Power to the People: Street Art as an Agency for Change A

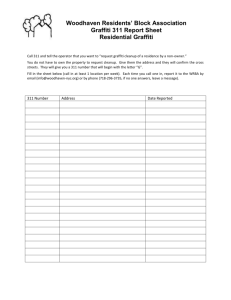

advertisement