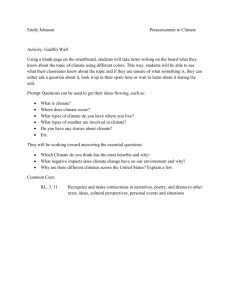

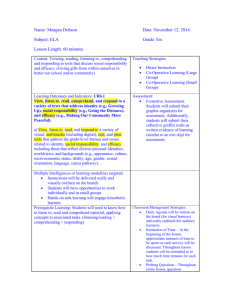

Making the case for legal graffiti as a legitimate form of public art in

advertisement