Barnes' Notes on the Bible

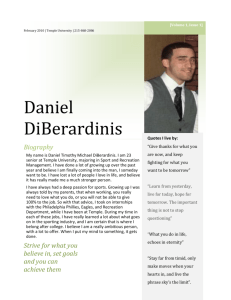

advertisement