Study Guide

Lord of the Flies by William Golding

For the online version of BookRags' Lord of the Flies Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please

visit:

http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-lordoftheflies/

Copyright Information

© 2000-2012 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Study Guide

1

Introduction

Despite its later popularity, William Golding's Lord of the Flies was only a modest success when it was first published in

England in 1954, and it sold only 2,383 copies in the United States in 1955 before going out of print. Critical reviews and

British word of mouth were positive enough, however, that by the time a paperback edition was published in 1959, Lord

of the Flies began to challenge The Catcher in the Rye as the most popular book on American college campuses. By

mid-1962 it had sold more than 65,000 copies and was required reading on more than one hundred campuses.

The book seemed to appeal to adolescents' natural skepticism about the allegedly humane values of adult society. It also

captured the keen interest of their instructors in debating the merits and defects of different characters and the hunting

down of literary sources and deeper symbolic or allegorical meanings in the story-all of which were in no short supply.

Did the ending of the story--a modern retelling of a Victorian story of children stranded on a deserted island--represent

the victory of civilization over savagery, or vice versa? Was the tragic hero of the tale Piggy, Simon, or Ralph? Was

Golding's biggest literary debt owed to R. M. Ballantyne's children's adventure story The Coral Island or to Euripides's

classic Greek tragedy The Bacchae?

Though the popularity of Golding's works as a whole has ebbed and grown through the years, Lord of the Flies has

remained his most read book. The questions raised above, and many more like them, have continued to fascinate readers.

It is for this reason, more than any other, that many critics consider Lord of the Flies a classic of our times.

Introduction

2

Author Biography

From an unknown schoolmaster in 1954, when Lord of the Flies was first published, William Golding became a major

novelist over the next ten years. only to fall again into relative obscurity after the publication of the generally

well-received The Spire in 1964. This second period of obscurity lasted until the end of the 1970s. The years 1979 to

1982 were suddenly fruitful for Golding, and in 1983 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. How does one

account for a life filled with such ups and downs? There can be no one answer to that question, except perhaps to note

that Golding's motto, "Nothing Twice," suggests a man with an inquiring mind who was not afraid to try many different

approaches to his craft. He knew that while some of his efforts might fail, others would be all the stronger for the

attempt.

Born in 1911, Golding was the son of an English schoolmaster, a many-talented man who believed strongly in science

and rational thought. Golding often described his father's overwhelming influence on his life. The author graduated from

Oxford University in 1935 and spent four years (later described by Golding as having been "wasted") writing. acting, and

producing for a small London theater. Golding himself became a schoolmaster for a year, after marrying Ann Brookfield

in 1939 and before entering the British Royal Navy in 1940.

Golding had switched his major from science to English literature after two years in college--a crucial change that

marked the beginning of Golding's disillusion with the rationalism of his father. The single event in Golding's life that

most affected his writing of Lord of the Flies, however, was probably his service in World War II. Raised in the sheltered

environment of a private English school, Golding was unprepared for the violence unleashed by the war. Joining the

Navy, he was injured in an accident involving detonators early in the war, but later was given command of a small

rocket-launching craft. Golding was present at the sinking of the Bismarck--the crown ship of the German Navy--and

also took part in the D-Day landings in France in June 1944. He later described his experience in the war as one in which

"one had one's nose rubbed in the human condition."

After the war, Golding returned to teaching English and philosophy at the same school where he had begun his teaching

career. During the next nine years, from 1945 until 1954, he wrote three novels rejected for their derivative nature before

finally getting the idea for Lord of the Flies. After reading a bedtime boys adventure story to his small children, Golding

wondered out loud to his wife whether it would be a good idea to write such a story but to let the characters "behave as

they really would." His wife thought that would be a "first class idea." With that encouragement, Golding found that

writing the story, the ideas for which had been germinating in his mind for some time, was simply a matter of getting it

down on paper.

Golding went on to write ten other novels plus shorter fiction, plays, essays, and a travel book. Yet it is his first novel,

Lord of the Flies, that made him famous, and for which he will probably remain best known. Golding died of a heart

attack in 1993.

Author Biography

3

Plot Summary

On the Island: Chapters 1-2

William Golding sets his novel Lord of the Flies at a time when Europe is in the midst of nuclear destruction. A group of

boys, being evacuated from England to Australia, crash lands on a tropical island. No adults survive the crash, and the

novel is the story of the boys' descent into chaos, disorder, and evil.

As the story opens, two boys emerge from the wreckage of a plane. The boys, Ralph and Piggy, begin exploring the

island in hopes of finding other survivors. They find a conch shell, and Piggy instructs Ralph how to blow on it. When

the other boys hear the conch, they gather. The last boys to appear are the choirboys, led by Jack Merridew.

Once assembled, the boys decide they need a chief and elect Ralph. Ralph decides that the choir will remain intact under

the leadership of Jack, who says they will be hunters.

Jack, Ralph, and Simon go to explore the island and find a pig trapped in vines. Jack draws his knife, but is unable to

actually kill the pig. They vow, however, to kill the pig the next time. When the three return, they hold a meeting. The

conch becomes a symbol of authority: whoever has the conch has the right to speak. Jack and Ralph explain to the others

what they have found. Jack continues his preoccupation with his knife. The boy with the clearest understanding of their

situation is Piggy. He tells them they are on an island, that no one knows where they are, and that they are likely to be on

the island for a very long time without adults. Ralph replies, "This is our island. It's a good island. Until the grownups

come to fetch us we'll have fun." One of the "littluns," the group of youngest boys, says that he is afraid of the "beastie."

The "biguns" try to dissuade him, saying there are no beasties on the island. However, it is at tins moment that Jack

asserts himself against Ralph, saying that if there were a beastie, he would kill it.

Discussion returns to the possibility of rescue. Ralph says that rescue depends on making a fire so that ships at sea could

see the smoke, The boys get overly excited, with Jack as the ringleader, and all but Piggy and Ralph rush off to the top of

the mountain to build a fire. They forget about the conch and the system of rules they have just made. At the top of the

mountain, Ralph uses Piggy's glasses to light the fire. They are careless and set fire to the mountain. Piggy accuses them

of "acting like kids." He reminds the older boys of their responsibility to the younger boys. At this moment they realize

that one of the littluns is missing.

The Beast: Chapters 3-11

The story resumes days later with Simon and Ralph trying to build shelters on the shore. Jack is away hunting. When he

returns, there is antagonism between Ralph and Jack. Jack is beginning to forget about rescue and is growing tired of the

responsibility of keeping the fire going, a task for which he has volunteered his choir. The growing separation between

the boys is marked by Ralph's insistence on the importance of shelter and Jack's on the hunting of meat.

In the next chapter, Golding describes the rhythm of life on the island. By this point, Jack has begun to paint his face

with mud and charcoal when he hunts. At a crucial moment, the fire goes out, just as. Ralph spots a ship in the distance.

In the midst of Ralph's distress, the hunters return with a dead pig. In the ensuing melee, one of the lenses in Piggy's

glasses gets broken.

Ralph calls an assembly to order to reassert the rules The littluns bring up their fear of the beastie yet again, saying that it

comes from the sea. Simon tries to suggest that the only beast on the island is in themselves; however, no one listens.

Ralph once again calls for the rules. Jack, however, plays to the fear of the boys, and says, "Bollocks to the rules! We're

Plot Summary

4

strong--we hunt! If there's a beast, we'll hunt it down ! We close in and beat and beat and beat!" The meeting ends in

chaos. Ralph, discouraged, talks with Piggy and Simon about their need for adults. "If only they could get a message to

us. If only they could send us something grownup ... a sign or something."

The sign that appears, however, comes when all the boys are asleep. High overhead rages an air battle and a dead

parachutist falls to the island. When the boys hear the sound of the parachute, they are sure it is the beast. Jack, Ralph,

and Simon go in search. Climbing to the top of the mountain, they see "a creature that bulged." They do not recognize the

figure as a dead parachutist, tangled in his ropes, and swaying in the wind.

When the boys return to the littluns and Piggy at the shelters, Jack calls an assembly. He calls Ralph a coward and urges

the boys to vote against Ralph. They will not, and Jack leaves. Ralph tries to reorganize the group, but notices that

gradually most of the biguns sneak off after Jack. The scene shifts to Jack, talking to his hunters. They go off on a hunt

in which they kill a sow, gruesomely and cruelly. They cut off the pig's head and mount it on a stick in sacrifice to the

beast. Meanwhile, Simon wanders into the woods in search of the beast. He finds the head, now called in the text "The

Lord of the Flies." Simon feels a seizure coming on as he hallucinates a conversation with the head:

Simon's head was tilted slightly up. His eyes could not break away and the Lord of the Flies hung in

space before him.

"What are you doing out here all alone? Aren't you afraid of me?'

Simon shook.

"There isn't anyone to help you. Only me. And I'm the Beast."

Simon's mouth labored. brought forth audible words. "Pig's head on a stick."

"Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill!" said the head. For a moment or two

the forest and all the other dimly appreciated places echoed with the parody of laughter. "You knew

didn't you? I'm part of you? Close. close. close! I'm the reason why it's no go? Why things are what

they are?"

Simon falls into unconsciousness. When he awakens, he finds the decomposed body of the parachutist, and realizes that

this is what the boys think is the beast. He gently frees the dead man from his ropes.

Back at the shelters, Ralph and Piggy are the only ones left. The two go to see Jack and the hunters, and they find a big

party. At the height of the party, a storm breaks and Simon arrives to tell them that there is no beast. In a frenzy, they kill

Simon. Later, Ralph, Piggy, Sam, and Eric are alone on the beach. All the boys agree that they left the dance early and

that they did not see anything. The four boys try to keep the fire going, but they cannot. Jack's hunters attack the boys

and steal Piggy's glasses so that they have the power of fire. Enraged, Ralph and Piggy go to retrieve the glasses. There is

a fight, and Roger, the most vicious of the hunters, launches a rock at Piggy, knocking the conch from his hands, and

sending him some forty feet to the rocks in the sea below.

The Rescue: Chapter 12

The scene shifts to Ralph, alone, hiding from the rest of the boys who are hunting him. The language used to describe the

boys has shifted: they are now "savages," and "the tribe." Ralph is utterly alone, trying to plan his own survival. He finds

the Lord of the Flies, and hits the skull off the stick.

Ralph sees Sam and Eric serving as lookouts for the tribe and approaches them carefully. They warn him off, saying that

they've been forced to participate with the hunters. When Ralph asks what the tribe plans on doing when they capture

him, the twins will only talk about Roger's ferocity. They state obliquely, "Roger sharpened a stick at both ends."

Plot Summary

5

Ralph tells the twins where he will hide; but soon the twins are forced to reveal this location and Ralph is cornered.

However, the tribe has once again set the island on fire, and Ralph is able to creep away under the cover of smoke. Back

on the beach, Ralph finds himself once again pursued. At the moment that the savages are about to capture him, an adult

naval officer appears. Suddenly, with rescue at hand, the savages once again become little boys and they begin to cry.

The officer cannot seem to understand what has happened on the island. "Fun and games," he says, unconsciously

echoing Ralph's words from the opening chapter. Ralph breaks down and sobs, mourning Simon and mourning Piggy. In

the final line of the book, Golding reminds the reader that although adults have arrived, the rescue is a faulty one. The

officer looks out to sea at his "trim cruiser in the distance." The world, after all, is still at war.

Plot Summary

6

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 Summary

Two boys make their way through dense jungle. They appear to be survivors of a plane crash. One boy has fair hair; the

other boy wears glasses and is described as being fat. He has asthma and cannot swim. He asks the fair-haired boy his

name; the fair-haired boy tells him, 'Ralph.' Ralph does not ask for the other boy's name in return. They find a pool of

water. Ralph, who is twelve, dives into it. The other boy reveals a nickname with which he was teased in school: 'Piggy.'

Ralph makes fun of him and yells the name several times.

The boys talk a bit, but Ralph is rude and occasionally even ignores Piggy altogether. They speculate as to whether or not

they are on an island and whether or not they will be rescued. Piggy refers to something the pilot of the plane said: about

the atom bomb. Therefore, he tells Ralph, everyone at the airport is dead and maybe no one would know the boys were

here to come and rescue them.

In the pool of water, Piggy spies a conch shell and helps Ralph retrieve it. Piggy informs Ralph that it can be used like a

trumpet. Ralph is so vague with his occasional responses that Piggy wonders aloud if Ralph knew the conch could be

used for this purpose all along. Ralph's silence allows Piggy to feel his suspicion verified. The boys climb up onto a

palm-shaded platform of pink granite, and Ralph starts blowing on the conch to call any other survivors of the crash

together. Soon, singularly or in groups, other children make their way to the platform. A handful of the boys are named

by the narrator: Johnny, who is about six years old; Jack Merridew, leading a group of marching choir boys in long black

cloaks and black caps; Roger, a choir member whom the narrator describes as slight and furtive; Simon, another choir

boy, who is faint with heat and exhaustion; and two twins, who are described as chunky and vital, and who fling

themselves at Ralph's feet like dogs.

Ralph conducts the meeting and suggests there should be a leader to decide things. Roger suggests they vote. Ralph, the

one holding the conch, wins the vote over Jack, with Jack only receiving votes from the choir out of obedience. Ralph

tells Jack the choir belongs to him and that they could be the army. Jack prefers that they be hunters, and so they are

called that. Ralph announces it to make it official.

Ralph organizes an expedition to find out if they are on an island or not, and he wants time to think about what is best to

do first. He chooses Jack and Simon to accompany him. Piggy wants to come too, but Jack discourages him. Piggy says

he was there when Ralph found the conch (even though Piggy himself actually spotted it first). Ralph then also tells

Piggy he needs to stay. Piggy follows to tell Ralph he is upset that Ralph told the boys the nickname he dislikes. Ralph

tells him it is better than being called 'Fatty' and gives him the job of getting every boy's name. Piggy feels gratified

somewhat by being given a job and returns to the group.

Ralph, Simon, and Jack continue their foray. They enjoy a sense of comradeship and excitement. They discover animal

tracks and marvel over the land's character and head up a mountain to gain the best vantage point. They consider trying

to make a map of the island using scratches on bark. They heave a large, pink square of granite over the side of a cliff,

smashing a hole in the canopy of forest below them. When they reach the top of the mountain, they see that they are

indeed on an island. Ralph says the island belongs to them.

They can see where their plane crashed, a scar ripping from the beach into the forest. They feel friendship for each other

in the initial excitement of learning they are alone on the island. Ralph says they can explore further to make sure the

island is definitely uninhabited, and Jack says they can hunt and catch things until "they" (the grownups) fetch them.

Simon mentions being hungry, and the other two feel their own hunger.

Chapter 1

7

On their way back to the beach, they encounter a piglet caught in some creepers. Jack draws his knife, but in the

moments he hesitates to kill it, the piglet escapes and runs away. Ralph and Simon are critical of Jack who alludes to the

next time, vowing he will not make the same mistake again.

Chapter 1 Analysis

Ralph's not asking Piggy's name when they first meet and his general rudeness toward him, especially under their present

circumstances, indicate Ralph's great selfishness and egocentricity: he acts as though he is quite certain he has no need

for Piggy whatsoever, and he certainly does not expend his energy in giving any kindness which might be solely for

Piggy's benefit.

When Piggy finds the conch and tells Ralph of its potential use, he very easily rewrites what really happens even in his

own mind, telling himself and later others that Ralph found it and that he was just with him at the time. This may be

evidence of Piggy's having become used to occupying a subordinate position with others, to misrepresent himself when

necessary, and to make himself appear less than he is in order to buy friendship.

What sets Ralph apart most of all, in the boys' minds, is the conch. His attractive appearance and his size contribute to

the sentiment, but it is the shell, the trumpet-thing, which wins Ralph a vote from every boy except from the members of

the choir in the election for chief. In this, the conch begins to take on powerful symbolic meaning in the story.

On their exploratory trek, Ralph, Jack, and Simon sense only the excitement of having an island to themselves and none

of the attendant responsibility. In beginning to imagine the possibilities for themselves, they start with what were once

but dreams of opportunity and place. Pushing the large rock and imagining the map etched on bark are like the stuff of

many boys' childhoods, and even then only from pages in a book; now they can play out their daydreams in reality.

The meeting with the piglet and the boys' failure to kill it serve as a reality check on the boys' optimism and euphoria.

They are hungry, and yet the magnitude of killing a living creature is not lost on them. Though Jack's hesitation was

probably felt by all three boys, none want to admit their fear and in their false bravado, Jack is effectively emasculated.

Chapter 1

8

Chapter 2

Chapter 2 Summary

The choir is less of a group by later in the day when Ralph blows the conch for a second meeting. He announces that they

are on an island. Jack and Ralph mention the pigs on the island which they can eat. Ralph tries to plainly explain their

situation and to implement some order, some rules, beginning with the conch, which he declares will indicate whose turn

it is to speak. Piggy shares his realization that it may be a long time before anyone finds them because nobody knows

where the boys are. Then a boy of about six years old wants to speak; Piggy interprets for him. He wants to know what

Ralph is going to do about the snake-thing, the beastie. He says he saw it in the woods. At first there is laughter. Ralph

dismisses the suggestion that there is such a thing, saying the boy must have had a nightmare. The boy will not relinquish

his fear, and Ralph grows increasingly angry as he insists again and again that there is no beast on the island.

Ralph tells the boys about his father in the Navy, how the Queen has a big room filled with maps, and how all the islands

of the world are drawn there, including this island. The boys clap and cheer, feeling more safe thanks to his words. He

then explains how the boys need to have a fire to make a smoke signal in case a ship should pass near enough by the

island to see it. At the mention of making a fire, the boys tumble away from the meeting place and run into the forest

toward the mountain. Ralph and Piggy agree they are all acting like a crowd of kids.

At the top of the mountain, the boys make a pile of wood. Ralph and Jack feel their tie of friendship growing. Some of

the boys wander off to explore the forest. They use Piggy's glasses to start the fire. The fire soon dies away. The boys

agree that they need more rules. Jack says that because they are all English, and the English are the best at everything,

that the boys have to do the right things.

Ralph puts one boy in charge of keeping the fire going this week and chooses another boy for next week. Piggy looks

beyond them, down the unfriendly side of the mountain, and sees fire devouring the forest below them, sounding like a

drum-roll. The boys cheer excitedly. Piggy is teased. He then remembers seeing one little boy, the one who talked about

the beastie, down in the forest where the fire now rages. Ralph places some of the blame on Piggy for not getting all of

the boys' names. Piggy starts to have an asthma attack, and wonders aloud where that little boy is now. The crowd was as

silent as death.

Chapter 2 Analysis

The group identity of the choir, now renamed Jack's hunters, is dissolving before that of the larger set of boys as a whole

has begun to. In the day's second meeting, whereas Ralph rushes to create the rule of needing to hold the conch in order

to talk, Piggy voices an observation of greater implication that it may take a long time for any grown-ups to find them

because no one knows where they are. This shows that while Ralph has the power to make rules, Piggy has a keener

perception.

Ralph's angry insistence that there is no beast cannot be borne out logically: he is no expert on the subject and he has not

been all over the island, so how could he know precisely what does and what does not live on the island? But his

description of the Queen's map room and the shared vision of his father heroically finding them all assuage whatever

doubts many of the boys have about their leader's sagacity. This points to the group's willingness to blindly accept their

leader's words, especially when the words are what it wants to hear. Ralph's best idea, that of a smoke signal, is embraced

with an enthusiasm as short-lived as the fire itself. Again, in the glow of its initial charm, having a fire seems like a great

thing to do, but few are prepared for the actual toil required to keep it going. Even after seeing how quickly the fire can

be let to go out, Ralph grossly overestimates the boys' ability to keep it lit, assigning one boy per week to tend the fire.

Chapter 2

9

The forest fire, started through the boys' neglect and ignorance, is truly deadly: the young boy who worried about the

beastie was last seen among the trees now being consumed by the conflagration. This could serve a jolt strong enough to

make the boys pause and carefully reassess their situation.

That the fire rages on the "unfriendly side of the mountain" suggests that the mountain itself has feelings, has desires, that

it is in effect, a beast of sorts. At the very least, it is being depicted as something capable of aligning itself with other

powerful forces to wreak havoc on these boys' lives.

Chapter 2

10

Chapter 3

Chapter 3 Summary

Time elapses. Jack's hair is lighter, his body tanner, his bright, blue eyes seeming nearly mad as he hunts in the forest.

Unsuccessful, he returns to the beach where Ralph and Simon are trying to roof a shelter. All of the other boys are off

playing. Tension builds between Ralph and Jack: Ralph wants more help with the shelters; Jack wants to continue

hunting even though he has not killed anything yet. Ralph asks Jack if he has heard the little ones' cries in the night. Jack

has not noticed. Simon breaks into their conversation, finishing one of Ralph's sentences, saying it is as if they think it is

not a good island. Then he mentions the snake-thing, the beastie, and Ralph and Jack both flinch upon hearing the

shame-evoking word, snake, which reminds them of the little one who died.

Ralph alludes to their first exploratory trek up the mountain, and the tension between the two eases. Jack explains how,

when he is hunting alone, sometimes it feels like he is not the only hunter in the forest. Ralph is incredulous and

indignant. Ralph tries to get Jack to understand the importance of keeping the fire burning in order to be rescued, but

Jack keeps returning to thoughts about killing a pig. They shout back and forth about the fire, the shelters, and the pigs.

They are both astonished at the friction between them. They go to bathe in the lagoon, with Jack thinking about hunting

and Ralph thinking about the shelters. They walk beside each other like two continents of experience and feeling, unable

to communicate.

Simon goes into the forest. He picks fruit for the littluns and then heads for a spot he has found. After making sure that

no one else has seen him, he squirms into a space hidden by dense creepers and leaves. As darkness falls on the island,

the candle-buds open, their scent spills out and takes possession of the island.

Chapter 3 Analysis

Jack is already described as looking nearly mad as he hunts. When Jack is unsuccessful in his hunt, he returns to Ralph

and asks for some of his water. From the way Ralph, Simon, and Jack are the only boys spending their time

constructively, one sees that the jolt of the deadly forest fire was not strong enough to change the course of most of the

boys' thinking. Tension is seen to ebb and flow between Ralph and Jack. Jack's obsession with hunting and killing pigs

and Ralph's obsession with keeping the fire burning are starting to pull them apart from each other. Perhaps their

respective obsessions are symbolic of two forces at odds with each other in the world. The fire and the smoke signal are

what can bring the boys back to civilization and its structure of laws and consequences. The hunting is not necessary for

survival because the boys can live off the fruit growing on the island. Though they would understandably have a desire

for something more filling than bananas and some jelly-like fruit, the meat and the killing to obtain it seem to represent

something darker, something inside each human that one either manages to kill off or keep hidden, sometimes from

himself as well as others.

The candle-bud scent taking possession of the island is another example of the nature imagery which paints the island's

natural characteristics as being sentient and possessing intention.

Chapter 3

11

Chapter 4

Chapter 4 Summary

The boys are becoming used to a new rhythm of life: the pleasures of morning, ducking the heat and ignoring the

miraculous mirages of midday, and then restlessness in the shelters under darkness. The younger boys suffer terrors at

night; all of them are filthy and very brown. They still come when Ralph blows the conch, in part because Ralph blows it,

in part because they link him to the adult world, and in part for the entertainment which the assemblies provide.

Otherwise, they keep mostly to themselves.

Three of the younger boys are playing on the beach around a sand castle. Roger and Maurice, two of the older boys,

come out of the forest toward the water and walk through the littluns' game, kicking sand as they go. Maurice still feels

the unease of wrongdoing and mutters something like an excuse before he runs into the water. Roger stands watching

them. One of the younger boys, Henry, leaves his playmates, walks down the beach and busies himself at the water's

edge. Roger follows Henry at a distance and hides himself at first, but then steps out into full view. Henry is so absorbed,

however, that he does not notice Roger. Roger throws nuts at Henry, purposely missing him. When Henry looks about to

see who is throwing them, Roger hides himself behind a palm. Henry soon loses interest and wanders down the beach.

Jack comes up behind Roger and calls his name. When Roger sees Jack, a shadow creeps beneath his skin, but Jack does

not notice. Jack begins talking to Roger about pig-hunting as though he were continuing a conversation begun only

moments earlier. Jack puts clay on his face, calls it dazzle paint, like the camouflage used in war. When he has painted

his face with red, white, and black, he looks at his reflection in a water-filled coconut and sees an awesome stranger. He

dances, makes snarling noises, and the mask becomes a thing on its own, and liberates Jack from shame and

self-consciousness. Jack dances toward Bill who at first laughs, but who then falls silent and stumbles away into the

bushes. Then Jack rushes toward the twins. Jack wants to play, but there is hesitation around him.

Ralph, Simon, Piggy, and Maurice are swimming in or idling near the lagoon. Piggy says he has been thinking about

making a clock, a sundial. Ralph, categorizes this idea with many of the far-fetched ideas flung about in the past by the

other boys who also suggested making an airplane, a TV set, and a steam engine. Even Ralph barely endures Piggy, and a

tacit understanding has developed among the older boys that Piggy is an outsider. Ralph makes fun of Maurice's entry

into the water, and moments later, Ralph is screaming, "Smoke! Smoke!" The other boys cannot see the ship. Ralph says

to himself that they will see our smoke. Ralph, still staring intently out to sea, asks Piggy if they have any smoke on the

mountain. Piggy asks Ralph if there is a signal, and Ralph starts to run and enters the forest. He is in a panic of wanting

to be at the mountain-top before the ship passes entirely away. The forest growth tears at his body. When he gets to the

fire, it is dead, and the ship is gone. Ralph yells for the ship to come back again and again.

Simon, Maurice, and Piggy arrive on the mountain-top; then a procession arrives with Jack and the twins carrying a pig

they have killed. They chant an eerie song of bloodlust.

The procession stops, and Jack begins to tell of the hunt. Ralph tells Jack he let the fire go out. At first, this seems

irrelevant to Jack. Then Ralph tells him there was a ship. Jack's face flushes with the consciousness of his fault. Ralph

tells him they could have been rescued if the fire had been going and there had been smoke. Piggy cries, and Ralph

pushes him. The truth filters down to everyone. Jack's face gets very red; he hacks and pulls at the pig carcass. Jack says

he needed everyone for the job. Piggy's criticism of Jack and several cries of agreement from others drive Jack to

violence: he punches Piggy in the stomach and smacks him on his head, causing his glasses to fly off. One lens breaks on

the rocks. Jack makes fun of Piggy, and Ralph cannot restrain his lips from twitching slightly. Jack apologizes for letting

the fire go out, but Ralph does not respond with generosity and instead repeats that it was a dirty trick to let the fire go

Chapter 4

12

out. Then he tells them to light the fire.

The activity of lighting the fire causes some of the tension to ease, and Jack is loud and active. Ralph remains silent and

still, and ultimately the group makes up the fire in a less convenient place so as to not need Ralph to move. One reads

that Jack is powerless and rages without knowing why, and when the pile of wood is built for the fire, Jack and Ralph are

also on different sides of a high barrier. When it was ready to light, Ralph takes Piggy's glasses from him and lit the fire,

not knowing how he was snapping a link between himself and Jack and forming it elsewhere. The boys find the best way

to cook the meat and eat. There is some argument about who gets to eat it and who does not. Jack takes a position of

authority in granting the meat and explains how they killed it. The twins jump up and run around each other. The others

join in, making pig-dying noises and shouting. Then Maurice pretends to be the pig, runs squealing into the center, and

the hunters pretend to beat him. As they dance, they sing and chant their eerie chant. Ralph watches, envy and resentful.

When the dancing and shouting die down, Ralph says he is calling an assembly and walks down the mountain.

Chapter 4 Analysis

The boys are becoming wilder, in appearance and behavior. The days upon days without supervision or consequence are

beginning to tempt some of the boys to test once-enforced boundaries of behavior. Through the incident with the sand

castles, one sees that Maurice still feels a dim pang of conscience, but Roger seems nearly immune to it. One feels the

utter vulnerability of all of the younger boys through Henry, so innocent and good-natured that he does not imagine

anyone might wish him harm. Jack must have seen what Roger had been doing, but he makes no mention of it; therefore,

one might presume that if he did see Roger throwing the nuts very near to Henry that he did not care.

Jack's war paint unleashes the hidden dark side within him. When Bill falls silent and stumbles into the bushes, one

suspects that it is not the superficial appearance of Jack's colored face that is so scary, but rather the emergence of

something which Jack has possessed all along but which, only when he is half-hidden by paint, becomes visible.

Ralph exposes his dim-wittedness in conversation with Piggy when he suggests that making a sundial is as difficult as

making an airplane or a boat.

The extinguished fire and the missed chance to be rescued places a wedge between Ralph and Jack. Though Ralph is

master of the fire, Jack is master of the meat. After the group dances and chants, Ralph wants immediately to reassert

himself and his values, so he calls an assembly.

Chapter 4

13

Chapter 5

Chapter 5 Summary

Ralph paces in the sand, thinking. He turns to the platform in a maze of thoughts and lacks the words to express them. He

notices how unpleasant his clothes feel: stiff, frayed, and dirty. He realizes his dislike of flicking his tangled hair out of

his eyes and rolling in the dry leaves at night.

Ralph begins the assembly, the purpose of which he says is to put things straight. He talks about the system of filling

coconut shells with water that was begun and aborted; he mentions the shelters that too few of the boys helped to build;

he reiterates the need for the boys to use a certain rocky area as a lavatory; and he brings up the fire. Ralph says they

need to make smoke on the mountain-top or die and creates a new rule: no fire anywhere on the island except on the

mountain. He says that things are breaking up, though he is not sure why. People have started getting frightened, he says.

His hair creeps into his eyes again. He says they have to talk about this fear and decide there is nothing in it. A picture of

three boys walking along the beach flits through his mind. Jack breaks in. Ralph reminds him he has the conch. Jack

takes the conch, boasts of being a hunter, of being all over the island by himself and says that he has seen no beast. Piggy

takes the conch, and in the midst of the teasing and name-calling, he says there is no fear, unless the boys become

frightened of people. A half-jest, half-jeer rises from the seated boys.

A little boy, Phil, takes the conch and tells about having a dream in which he saw twisty things in the trees. Ralph

disregards it as a nightmare. Simon takes the conch and admits to being out in the forest at night, revealing reluctantly

that there is a place he likes to go. Jack says something demeaning to Simon. Ralph feels humiliation on Simon's behalf

and takes the conch back, telling Simon not to do that again. Another boy wishes to speak, Percival. With Piggy's help,

Percival says the beast comes out of the sea. The assembly erupts into angry shouts. Simon tries to suggest that the beast

to be feared is the boys themselves, but he is unable to express "mankind's essential illness." Someone says that maybe

Percival means it is a ghost, and then the group becomes unruly again. Ralph tries to impose order on the group by

suggesting a vote on whether or not there are ghosts. Ralph peers into the gloom and makes out hands raised, and how

"the world, that understandable and lawful world, was slipping away."

Piggy has the conch and tells everyone to remember that he said he does not believe in ghosts. Jack tells Piggy to shut up

and that he is a fat slug. Ralph tells Jack to let Piggy speak, that he has the conch. Jack challenges Ralph's authority.

Ralph answers that he is chief, that he was chosen. Jack asks why choosing makes any difference and accuses Ralph of

giving orders that make no sense. Ralph reminds Jack that Piggy has the conch; Jack accuses Ralph of favoring Piggy

and mocks him. Ralph reminds them of the rules; Jack says who cares about the rules. Ralph says the rules are the only

thing they have got. Jack is shouting and soon "the assembly shreds away and became a discursive and random scatter

from the palms to the water and away along the beach."

Ralph, Piggy, and Simon are the only three left on the platform. Ralph considers giving up being chief. Piggy asks what

would happen to him if Ralph stopped being chief. Simon also encourages Ralph to continue being chief. Piggy says he

is afraid of Jack and tells Ralph that Jack hates him. Piggy tells Ralph that if Ralph steps aside, Jack will hurt the next

thing, and that is Piggy. Simon again encourages Ralph. Ralph says they are all drifting and things are going rotten. He

says they need to keep the fire going. They talk about how grown-ups do things and what they would or would not do if

they were on the island. Ralph cries out desperately, wishing the grownups would send them a sign. Percival screams in

the distance.

Chapter 5 Analysis

Chapter 5

14

Though the rules Ralph is trying to enforce are sound, the fog of Ralph's mind deepens. Implementing them also requires

the other boys' participation, which is more and more slow in coming. The discomfort of his clothes may symbolize his

looking for more superficial and benign reasons for his growing unease and his unwillingness to see the real cause.

Ralph's tangled hair, which keeps getting in his eyes and makes it difficult for him to see, and the struggle to rest at night

on his bed of noisy, dry leaves point to how the wildness which Ralph is trying to keep at bay with his rules is gaining

ground. Instead of civilizing the island, the wildness of the island is reclaiming the boys.

Early in the chapter, Jack shows that he still is bound by the rules, but later in the chapter, he becomes more openly

defiant. Ralph's attempt to impose order begins to go astray, and as his grip as leader slips, his influence wanes. Ralph

has opportunities to defend weaker members of the group, such as Piggy and Simon, but he fails to do so because there is

enough cruelty in him to cause him to identify with the bullies and enough of the old, childlike need for acceptance that

he learned on the playgrounds and in the classrooms of his former days to stay him from defending those who need his

defense. This flaw in his leadership begins as a crack which provides room for the fledgling weeds of Jack's influence to

grow; this crack becomes a chasm to never-again be bridged.

The way the group shreds away from the assembly describes the way the fabric of this delicately balanced society is

quickly fraying.

At the beginning of the story, Ralph is evidently pleased to find himself on an island without any grown-ups. This

sentiment has faded clean away, however, by this point in the story, and Ralph considers longingly what grown-ups

would do in their situation: they would have tea and discuss things. The same activities that he likely chafed at in days

prior, he now wishes for desperately.

Chapter 5

15

Chapter 6

Chapter 6 Summary

During the night, a man, already dead, drifts down in his parachute from his exploded plane and lands on the mountain

not far from the fire pit. The twins have fallen asleep during their fire-watch on the mountain-top. When they awaken and

again get the fire going, one suddenly sees and points out to the other a dark shape lodged between some rocks where

previously there was none. They run down the mountain and report to Ralph that they have seen the beast. Ralph calls an

assembly. He merely holds up the conch instead of blowing it, and all the boys understand. Ralph hands the conch to the

twins who tell of seeing the beast. Jack wants to hunt the beast and asks for volunteers. Ralph suggests putting Piggy in

charge of the littluns while the hunters search for the beast. Jack says they do not need the conch anymore. Ralph tells

Jack to sit down, but Jack remains standing. The boys watch intently. Ralph reminds the boys about needing the fire to be

rescued, and their sympathy swings back to Ralph once more.

They decide to search the castle first, the only place Jack says he has not yet been. Ralph lets Jack lead the expedition,

walking in the rear and thankful to escape the burden of responsibility momentarily. They reach the castle, and

something deep in Ralph causes him to say he is chief and he will explore the castle alone and tells the others not to

argue. Ralph does not expect to find a beast, but he does not know what he will do if he does find one. Jack follows him

and tells him he could not let him go alone. They see a huge rock and Jack says how if an enemy were to come, they

could push the rock off the ledge onto him. Ralph notices there is still no fire, no signal. Ralph says they need to go look

up on the mountain, and they leave the castle.

When the other boys see them leaving the castle, they run onto it, push a great rock over the edge into the water, and

generally make loud noise. Ralph yells at them to stop and reminds them that they need to make smoke. Roger says they

have plenty of time. Some boys want to return to the shelters; some boys want to swim at the beach; some want to make

a fort out of the castle. Ralph yells that he is chief and that they need to know for certain about the beast. He reminds

them there may be a ship out at sea and asks them if they are all crazy. "Mutinously," the boys went either silent or

muttered. Jack leads the way off the rock and across the bridge which joins the castle to the island.

Chapter 6 Analysis

Ralph and Jack's struggle for power escalates. The need for the fire is understood, indicating that the boys are still

capable of rational thought. At the same time, the way the boys watch Ralph and Jack so intently suggests a certain

unwillingness, or perhaps inability, on their part to imagine the consequences of Jack's usurpation of authority.

Jack does follow Ralph instead of staying back as Ralph instructs, but Ralph does nothing to enforce his command; in so

doing, he allows Jack to leach a bit more of his authority away. One sees how Jack's violent nature is coming closer to

the surface as he becomes less inhibited. At the castle he mentions how they could kill an enemy, but there are just boys

on the island, no enemies. Jack needs an enemy upon whom he can unleash his destructive energy: and one begins to

suspect that Jack is the type to create an enemy if one, in reality, does not exist.

The boys running amok all over the castle and seeming deaf to Ralph's reminder about the fire shows how the orderliness

of the group is dissolving. Jack leads them off the castle rock, which may indicate that he is not entirely immune to

Ralph's reasoning, or it might just be that he is linking himself opportunely to the leader's role.

Chapter 6

16

Chapter 7

Chapter 7 Summary

Ralph, Jack, and others are hunting the beast. They stop to eat some fruit. Ralph makes plans to clean himself up, wash

his clothes, and cut the hair that keeps falling into his eyes. All of the boys are thoroughly filthy, their clothes nearly

worn away. They are on the opposite side of the island which boasts their lagoon, and Ralph ponders the vastness of the

sea. It is easier to dream of rescue in the lagoon than it is here. Simon tells Ralph that Ralph will get back home. Roger

calls for all to come and see the fresh pig droppings he has found. Although they are hunting the beast, Ralph consents to

hunt pigs as long as doing so does not take them out of their intended route to find the beast. When there is a pause in the

progress, Ralph daydreams. He dreams of days long ago with his Mummy and Daddy when everything was all right,

good-natured and friendly. He is awakened from his reverie to see a pig bounding toward him. He calmly throws his

spear at the boar; the boar squeals and then swerves aside. Jack chases after it. Due to the respect he seems to have won

from the other boys from having hit the boar, Ralph thinks hunting may be good after all.

Jack cannot find the boar, comes back and criticizes Ralph. Jack points out a bloody wound on his arm the boar gave him

with its tusks. Ralph tries to regain their attention, talking about how he hit it with his spear. A boy named Robert

suddenly pretends to be the pig, snarling. Ralph enters into the play, and everyone laughs. The play turns mean and

hurtful, and Robert screams and struggles sincerely. Roger tries to get in close. Ralph also feels a strong desire to hurt.

The boys chant their eerie chant. Jack's arm comes down and the circle of boys cheers and makes pig-dying noises. They

lay panting as Robert snivels and complains about his hurt bum. Jack says that was a good game. Ralph, uneasy, says it

was just a game. The boys talk about how it could be made better with a drum and a fire. Jack says someone could just

pretend to be a pig. Someone else says it needs to be a real pig, so they can kill it.

Ralph reminds them all of the purpose of this mission. Some of the boys do not want to go to the mountain. Ralph

reminds about the fire. Jack says they do not have Piggy's glasses, so they cannot re-start the fire anyway. Ralph says

they will find out if the mountain is clear. Again, Jack takes the lead and Ralph dreams. The boys have chosen a difficult

route and generally make slow progress. Still far from the mountain, he decides to send one boy to tell Piggy they will be

back after dark. Simon volunteers to go. Jack tells Ralph there is a pig-run not far from where they are, and Ralph

decides they will look for it to make their passage easier. Jack challenges Ralph, saying he will not mind searching for

the beast when they get to the mountain and asks Ralph if he would rather go back to Piggy. Ralph asks Jack why he

hates him. The other boys act as though something indecent has been said, and Jack says nothing. Ralph turns away

before Jack responds and leads the way while Jack brings up the rear.

Evening is approaching and there is some talk about resting on a platform and finishing the climb to the mountain-top in

the morning. Jack taunts Ralph and says he is going up the mountain. Then he asks Ralph if he is coming. So Ralph,

Jack, and also Roger go the rest of the way up the mountain while the other boys stay back. Ashes from the burnt patch

of forest blow into their eyes. It is dark and Ralph thinks this is foolish. Jack says if he does not want to go, then Jack will

go alone. In his fatigue and fear, he angrily tells Jack to go ahead and that he and Roger will wait there. Jack goes up

alone, leaving Ralph and Roger sitting on a charred tree. Roger sits quietly, tapping his stick against something, irritating

Ralph. They hear the sound of giant, dangerous strides taken on rock. Jack finds them; he says he saw a thing on top, a

thing that bulged. Ralph at first says he only imagined it; then he says they will go up to take a look too. Jack leads them

up. When the three get close, they are crouching, looking. Ralph stands up, takes two steps forward. The moon clears the

horizon, and Ralph sees something like a great ape. The wind blows and the creature lifts its head, revealing to them his

ruined face. They all stumble as fast as they can down the mountain.

Chapter 7 Analysis

Chapter 7

17

Ralph continues to daydream, wishing for the forms and conventions of civilization instead of tackling the much more

difficult task of looking soberly at the situation and being a true leader. His daydreams also suggest that on some deep

level, Ralph really does understand that their circumstances are becoming very dire, for he would not need to daydream

about when times were good-natured and friendly if things actually were good-natured and friendly on the plane of

reality. If they were, then he could go back to daydreaming about exploration adventures. Ralph again reveals his need

for approval, crippling whatever leadership ability he has left.

In forgetting Piggy's glasses to start the fire, he shows his lack of forethought. In allowing the group to take a very long

time to reach the mountain and daydreaming along the way, Ralph reveals his own reluctance to deal with the crisis and

suggests that the role of chief is indeed up for grabs. This expedition could be seen as the turning-point in the story when

the boys begin looking to Jack as their leader rather than to Ralph.

The eerie chant and the game which becomes painfully serious points to the growing animalism in the boys. They are

pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable and still have not felt a wall to constrain them. This only encourages them

to keep pushing further.

Chapter 7

18

Chapter 8

Chapter 8 Summary

Back on the beach, the boys relate their findings to Piggy. Piggy is incredulous. Jack tells him to go up and see for

himself. Ralph says the beast has teeth and big, black eyes. They talk about what to do. Ralph says if they cannot have a

signal fire, they are beaten. Jack blows on the conch, and they go to the platform where the littluns are also gathering.

Jack calls Ralph a coward, lies about Ralph's not going all the way to the mountain-top, and says he is not a hunter. He

asks how many boys think Ralph should no longer be chief. No one raises his hand. Humiliated, Jack leaves, saying he

will not be a part of Ralph's lot anymore and saying that anyone who wants to hunt with him can join him. He walks off.

Ralph yells for him. Piggy says they can do without Jack Merridew. They decide they will keep a fire going down on the

beach, and they will build it now. The wood was not as dry as it is up on the mountain. Simon leaves for his hiding place

in the forest.

Far from Ralph and the lagoon, Jack surveys the group of choir boys who have joined him. He tells them they will hunt,

and they will forget about the beast. They agree passionately with him. Jack tells them they will go to the castle rock, but

first he is going to get more of the biguns away from the conch and all that. He says they will kill a pig and give a feast.

He says they will leave some of the pig for the beast and maybe it will not bother them. Jack enters the forest, and the

boys follow him. Very soon Jack finds dung and fresh tracks. He finds some pigs enjoying the shade beneath the trees.

He leads the boys silently toward them and picks out for their object a sow, lying contentedly with her piglets either

sleeping or burrowing near her.

The boys wound her, but she runs off. The boys follow her for a long time and finally kill her. Roger asks Jack how they

can roast the pig without fire, and Jack says they will raid Ralph and the other boys and take some fire from them. Jack

tells Roger to sharpen a stick at both ends and to jam one end into the earth. Then Jack stuck the pig's head on the other

end. Loudly, he said that the head is a gift for the beast.

Simon, who has been hiding behind the leaves, sees the sow's head in his mind even when he closes his eyes. Flies cover

the discarded entrails of the pig, and soon they find Simon. In front of Simon, the Lord of the Flies hangs on the stick and

grins. Simon begins to hear a beat pulsing in his head.

Ralph and Piggy are one the beach, watching the fire. They need more wood, and they need more people to keep the fire

going. Ralph admits that sometimes he just wants to give up, but Piggy encourages him to keep going, like what

grown-ups would do. Two boys rush out of the forest, run to the fire, grab half-burnt branches, and race away. Three

other boys stand still watching Ralph and Piggy, one of whom is Jack. He tells Ralph and Piggy that he and his hunters

are living along the beach by a flat rock and if they want to join his tribe to come and see them. He tells them they have

meat and are having a feast tonight. Jack signals the two boys standing with him, who say in unison that the chief has

spoken. Then they all run off.

Ralph cradles the conch and goes to the platform. Piggy follows; then the twins, the littluns, and the others go too. Ralph

explains that the other boys raided them for fire, that he would like to dress up in war paint, but the fire is the most

important thing. One boy wants to go tell Jack and his group that keeping the fire going is hard on them, and some of the

boys talk about the meat they will be having.

The Lord of the Flies is talking to Simon, telling him to run and play with the others, that the other boys think he is batty,

and that there is not anyone to help Simon except him, and he is the Beast. The pig's head tells him, "You knew, didn't

you? I'm part of you? Close, close, close! I'm the reason why it's no go? Why things are why they are?" Simon knows

Chapter 8

19

that one of his times is coming on. The Lord of the Flies speaks in the voice of a schoolmaster, telling Simon he is not

wanted and that they are going to have fun on this island. Simon falls down and loses consciousness.

Chapter 8 Analysis

Ralph exaggerates his description of the beast; it may be that, in his terror, Ralph truly thought he saw what he said he

saw, or it may be that he purposely exaggerates in order to justify his frightened reaction. Piggy, who earlier declares he

does not believe in ghosts, says he does not believe in this beast on the mountain either: his is the only voice of reason

left.

Jack openly challenges Ralph's authority. None of the other boys wants to overtly overthrow Ralph for Jack, but many of

them leave secretly. This suggests that perhaps they realize it is not the wisest thing to do, but they do not stop

themselves from doing it anyways.

Jack's targeting the sow with young sums up his insensitivity and the careless cruelty of his logic. From a husbandry

point of view, it would be in all of the boys' interests to leave the sow and her young alone so that they can grow up into

another generation and thereby provide them with meat in the future. From the viewpoint of universal compassion, the

sow would not have been chosen as the hunters' object. Jack thus shows himself beyond reason and feeling, and his

fellow hunters are made equally culpable through their obedient participation.

At one time Ralph loudly blew the conch; then he merely held it aloft. Now he cradles it as if it is delicate. He appears

protective of it and of the increasingly-fragile memory of civilization which the conch may represent.

The Lord of the Flies is the sow's head on a stake, and the narrator also refers to it as the Beast. The words of the Lord of

the Flies to Simon are likely a summation of the author's intended central theme. It tells Simon that a flaw inherent in the

boys is the cause for the group's disintegration into chaos. In calling the head the Beast, the narrator also suggests that the

thing to be feared is not a monster on the mountain, but rather something within them all.

Chapter 8

20

Chapter 9

Chapter 9 Summary

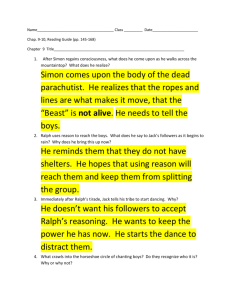

A blood vessel breaks in Simon's nose, and his fit passes into sleep. He awakens, sees The Lord of the Flies on its stick,

and wonders what else is there to do. He gets up and walks out onto a rock. A wind comes up and Simon sees a humped

thing suddenly sit up and look down at him. He looked more closely and understood the mechanics of the parachute. He

takes the lines in his hands and frees them from the rocks and the figure from the wind's indignity. He looks down at the

platform on the beach and sees that the fire there is almost out, but he sees another trickle of smoke rising from further

down the beach. He could see that most, if not all, of the boys were there. He knows now that the beast is harmless and

wants to get this news to all the boys as soon as possible.

Ralph and Piggy are by the swimming pool. Piggy notices that the boys are gone. Piggy says maybe they should go to

Jack's too to make sure nothing happens. When they get there, Jack tells someone to get Ralph and Piggy some meat.

Jack tells everyone to sit down. Then he asks them who is going to join his tribe. He tells them he got them meat and his

hunters will protect them from the beast. Ralph says he is chief because they chose him. Ralph reminds them of the

importance of the fire and reminds them that he has the conch. Jack points out that Ralph does not have it with him and

that it does not count at this end of the island anyway. Piggy whispers to Ralph about the fire and getting rescued. Jack

asks again who will join his tribe, and some boys say they will. It starts to rain, and Ralph asks what will they do for

shelters. Jack leaps up and yells for them to do their dance. Roger becomes the pig; the others grab weapons. The chant

becomes a steady pulse, thunder and lightning shoot down from the sky, and something crawls out of the forest. The boys

crowd around it while it yells about a body on the hill. They kill it, then stagger away, leaving the body a few yards from

the sea. It is small. It is Simon.

A great wind on the mountain-top fills the parachute and carries it toward the beach. Boys run screaming into the

darkness. The figure is drawn out to sea, and so is Simon's.

Chapter 9 Analysis

When Jack points out that the conch does not count at his end of the island, he shows that he is doing away with rules

and responsibility. When Ralph asks a pragmatic question about what they will use for shelters, Jack changes the subject

by ordering them to dance.

During the dance it storms, and the wildness expressed by the forces of nature are also unleashed from within each boy.

In the high-pitched state of consequence-less-ness, they are rendered also conscience-less, resulting in the death of

Simon.

Chapter 9

21

Chapter 10

Chapter 10 Summary

Ralph, Piggy, the twins, and some littluns are near the platform. Ralph has a fat eye and a skinned knee. Ralph asks

Piggy what they are going to do. They admit to each other that Simon was murdered. Piggy says they were scared. Ralph

says he was not scared, but he cannot say exactly what he was feeling. Piggy repeatedly says it was an accident, but

Ralph says Piggy did not see what they did. Ralph says he is frightened of all of them, even himself. Piggy tells Ralph

not to tell anyone that they were at the dance. Ralph says they all were. Piggy says he was only on the outside. Ralph

mutters that he too was only on the outside. Piggy and Ralph talk to the twins. They all avoid admitting to the unspoken

knowledge between them.

Roger goes to the castle rock. Robert shows him how a lever has been placed beneath the large, uppermost rock. A boy

named Wilfred has been tied up for hours, awaiting punishment, but Robert does not know why. When Roger joins the

rest of the tribe, Wilfred has been beaten and untied. Jack tells everyone that tomorrow they will hunt again, that some

will defend the castle, and that the beast might return. He reminds them of how the beast crept out of the forest,

disguised. One boy tries to ask did they not kill it the night before, and each boy flinches from his own memory, but Jack

yells no, how could they, and advises them all to leave the mountain alone. Another boy asks how they will cook the

meat, and Jack explains how they will take fire from the others.

Piggy and Ralph make a fire. Three boys are also with them. Ralph and Piggy go to the fruit trees and eat quickly. When

they return to the fire, only embers glow and there is no smoke. The twins are tired and wonder what is the use of trying

to keep the fire lit. Ralph tries to remember. Piggy reminds them all that they need a smoke signal to get rescued. The fire

is dying. Ralph reasons how the four of them need to take twelve-hour shifts minding the fire. The twins say they cannot

get more wood in the forest at night. Ralph says they can let the fire go out, just for tonight. The four biguns enter one of

the shelters and try to get comfortable.

The boys hear movement outside the shelter. A horrible whisper tells Piggy that it wants him to come out, and asks him

where is he. Then boys are in the shelter and there is a tangle of hitting and biting in the darkness until the invaders run

away. Ralph thinks the other boys came for the conch, so he runs to the platform to check on it and sees it still

glimmering by the chief's seat. He runs back and tells the three that they did not take it. Piggy says they did not come for

the conch and asks Ralph what is he going to do. Jack, trotting down the beach, is a chief now in truth. He makes

stabbing motions with his spear carrying Piggy's broken glasses.

Chapter 10 Analysis

Though Ralph does feel horror and shame about Simon, he also seems to feel something else he cannot quite name:

possibly a sick attraction for the beastly behavior which led to Simon's death. Piggy seems more conscience-bound. He

did not see as clearly what happened to Simon, was on the outside of the circle, and is able to at least entertain the notion

that the death was an accident. Ralph's puffy cheek makes his echoed claim of also having been on the outside of the

circle seem very weak. One twin has a scratch on his forehead and the other a split lip. No marks, however, are described

on Piggy. All four of the boys feel ashamed about the dance, but none of them appear to be experiencing grief or the need

to mourn the loss of Simon.

In Wilfred's bondage and beating, one quickly sees what kind of society Jack's leadership is creating. One boy struggles

to reconcile what he remembers from the night before with what Jack is telling his group, but his attempt is feeble and

easily abandoned. The following question, by another boy, about how they will cook the meat suggests the group's

Chapter 10

22

mentality and their willingness to forego thinking about the unpleasant or the complicated in favor of pursuing the

fulfillment of their immediate appetites.

Ralph's mental darkness grows. Earlier in the story, Ralph assigned one person to watch the fire for an entire week. Now

the shifts in tending the fire are only 12 hours long, and they all feel acutely the magnitude of the challenge.

Piggy's glasses are far more valuable to the boys' survival and rescue than is the conch. Ralph's adoration of the shell,

juxtaposed against his unwillingness or his inability to comprehend the real danger they are in, accentuates his ineptness

as a leader.

Chapter 10

23

Chapter 11

Chapter 11 Summary

Ralph, Piggy, and the twins gather on the beach where the fire should be. Piggy convinces Ralph to blow the conch and

call an assembly. Piggy, the twins, and some littluns meet Ralph on the platform. Ralph suggests they tidy up their

appearance, talk to the others, and remind them that they are not savages. The twins break in and suggest they bring

spears, even Piggy, because they might need them. Ralph yells about needing the conch to speak. Piggy says he wants to

go tell Jack what he thinks. Someone says he will get hurt, and Piggy asks what can Jack do to him that he has not

already done. He says he will demand his glasses back because it is the right thing to do. Ralph says they will go with

Piggy. The twins say Jack will be painted, that he will not think much of them, that they will have had it if Jack gets

waxy.

They eat from the fruit trees. Ralph sees cleaning up their appearance as impossible. The twins mention how the others

will be painted, but Ralph angrily refuses to allow them to wear any. Ralph reminds them about wanting smoke. Piggy

explains the more complete reason, saying that they need smoke to make a signal for a ship to rescue them. Ralph gets

angry that Piggy would suggest he has forgotten the smoke's purpose. Piggy tries to reassure Ralph by saying he knows

Ralph remembers everything. The twins look at Ralph as though seeing him for the first time.

When Ralph, Piggy, and the twins get to the castle, Ralph blows the conch. He tells Roger he is calling an assembly. The

boys guarding the neck leading to the castle make no motion. Piggy tells Ralph not to leave him. Ralph tells him to kneel

down and wait for him to come back. Roger takes his hands off the lever and leans out to watch. From his viewpoint, the

boys on the neck were just shaggy heads and Piggy was a shapeless sack. He throws a stone between the twins and feels

some power pulse in his body.

Ralph repeats that he is calling an assembly, that he has come about the fire, and about Piggy's glasses. Jack, who has

been off hunting, returns and tells Ralph to go away and keep to his end. Ralph tells Jack he has to give Piggy his glasses

back, that he played a dirty trick, and that if they had wanted fire, they would have given it to them. Ralph calls Jack a

thief, and they start fighting on the neck. Piggy reminds Ralph again about the purpose of their visit, and Ralph tries to

explain again to everyone how they need a fire to make a smoke signal so a ship will see them and rescue them, but his

words are met by the painted anonymity of the savages. Jack orders his boys to grab the twins; they capture them and tie

them up. Ralph screams at Jack, calling him a thief, and rushes toward him. Jack charges too and they fight. The crowd

cheers, but Piggy's voice penetrates to Ralph's ears, asking to speak. Piggy holds up the conch and yells that he has the

conch. He asks them all which is better: to be a pack of painted Indians or sensible like Ralph. Ralph shouts which is

better: law and rescue or hunting and breaking things. Jack is yelling too, his group behind him working up to a charge.

Then Roger leans on the lever, Ralph flings himself flat, and the tribe shrieks. Piggy is struck and goes tumbling forty

feet to his death. The conch is shattered into a thousand white pieces and ceases to exist.

Ralph's lips form a word, but no sound comes. Jack says that is what Ralph will get and that he meant that and that there

is not a tribe for him anymore, and that he, Jack, is chief now. Jack and Roger throw their spears at Ralph as Ralph

retreats. He ducks more spear throws and runs into the forest. The chief stops the chase and orders everyone back to the

castle. He prods the twins with a spear and questions. Roger almost pushes Jack, telling him that is not the way, and

advances upon them as one with a nameless authority.

Chapter 11 Analysis

Chapter 11

24

The twins are right: spears would be very useful, but Ralph is still worrying about decorum even when lawlessness is

about to engulf them. The twins see Jack more clearly than Ralph does. Seeing Piggy remind Ralph about the fire helps

the twins see Ralph more clearly too.

When Ralph blows the conch at castle rock, one gets the feeling that this is too little too late. None of the boys, whom the

narrator now calls savages, give any indication of caring about making smoke anymore. Piggy's senseless death and the

destruction of the conch symbolize the tribe's abandonment of all reason and its descent into utter lawlessness. Piggy's

nickname ties him inextricably to both the animals hunted on the island and to the unfortunate sow's head which Simon

thought spoke to him. Perhaps this link is meant to instruct us about the temptation to hurt, if not kill, a weaker being. Or

perhaps it is to show how humans have been known to prostitute their values in order to purchase acceptance, often at the

expense of total personal debasement.

Chapter 11

25

Chapter 12

Chapter 12 Summary

Ralph lies in a culvert not far from castle rock. He considers his situation. Peeking out and up, he sees that the tribe has

begun its feast. He cannot fool himself into believing they will not carry out their plans against him, but part of him tries

valiantly to persuade himself to believe that what happened to Piggy was an accident. He eats greedily from the smashed

fruit. He thinks the best thing to do is to ignore the leaden feeling in his heart and rely on the tribe's common sense, their

daylight sanity. He does not want to sleep by himself in an empty shelter, so he limps back toward the castle rock.

He sees the pig's head, gleaming as white as the conch, atop its stick and it seems to jeer at him cynically. He hits out at

it, breaking it into two pieces, and backs away, holding the stick as a spear. When night falls, Ralph again comes into the

thicket near castle rock. He wonders if he could walk into the fort, laugh about the past, and sleep among the others,

pretending they were still boys. However, lying there in the dark, he knows he is an outcast. He sees that the twins are

guarding the castle top, so he sneaks over and climbs the rocky wall to talk to them. They tell Ralph he needs to go, for

his own good, to hide. Ralph cannot quite find words. He notices they are not painted. The twins defend themselves by

saying the tribe made them join and that they hurt them. They tell him again he has to go, for his own good, that the chief

and Roger hate him, and they are going to hunt him tomorrow. The twins tell Ralph about the call signal they will use

when they hunt him tomorrow. Ralph asks what they will do to him. Someone from the tribe starts to come up to the top,

so Ralph has to go. Ralph tells the twins where he will hide so they can keep the hunters away from him. The twins give

him some meat and answer his question, saying that Roger has sharpened a stick at both ends, but Ralph does not know

what this means.

When he gets to the bottom again, he hides. He hears the twins arguing with someone. He pulls himself between some

ferns and falls asleep. He awakes to hear the call the twins described sweeping across the island. He takes his sharp stick

and wriggles into ferns and then into a thicket. He finds an area of land indented by the rock that killed Piggy and

huddles within it. His confidence is shattered when he hears Jack's voice asking another savage if he is sure. One of the

twins moans and squeals, and Ralph knows they know where he is. The tribe heaves two enormous rocks off the cliff,

aiming for where he is hiding. Then savages are shaking the branches near him. He sees a stick and thrusts his own stick

with all his might, wounding someone. He worms his way through the thicket and starts running through the forest.

He feverishly tries to reason out the best hiding place. Listening for the hunters, Ralph notices another noise, a deep

grumbling noise, which he knows he has heard before. He realizes that in trying to smoke him out of his hiding spot, the

tribe has set the island on fire. He finds a spot behind a thick tangle of creeper that keeps out all the light of the sun. He

worms into the middle of it, waits, and listens. He thinks how he can break out and continue running if he is found. He

hears cries nearer. He sees a savage getting closer and closer and kneeling down and peering into the darkness which

covers Ralph. Ralph looks straight into the savage's eyes. He screams out of fright, anger, and desperation. He shoots

forward, crying out. He avoids a spear thrown at him and runs, forgetting his pain, his hunger, his thirst.

He trips over a root and the cry that pursues him rises higher. He sees a shelter burst into flames around him. He falls into

warm sand, raises an arm to ward off a blow, tries to cry for mercy. When no blows fall on him, he staggers to his feet

and looks up to see a naval officer standing in front of him. The hunters' cries falter and die away. Behind the officer

Ralph sees a cutter and a sub-machine gun. The officer says hello to Ralph; Ralph answers hello back. The officer asks if

there are any grownups with them, and Ralph shakes his head no. The officer thinks he is witnessing the boys' fun and

games.

Chapter 12

26

The officer tells Ralph they saw the smoke coming from the island and asks if the boys were having a war. Ralph nods.

The officer says he hopes nobody has been killed. Ralph says there were only two, and they have gone. The officer leans

down, looking closely at Ralph, and asks if two were killed. Again, Ralph nods. The officer believes him and whistles

softly. The other boys are now standing on the beach watching; the whole island in engulfed in fire. The officer asks how

many are there. Ralph shakes his head. The officer asks who is in charge, looking toward the group of painted boys.

Ralph answers loudly that he is in charge. One boy, carrying the broken remains of a pair of glasses at his waist, starts

forward but then changes his mind and stands still.

The officer asks again if Ralph knows how many boys there are. Ralph says no. The officer says he would have thought

that a pack of British boys would have put up a better show than that. Ralph says it was like that at first, but he cannot

finish his sentence. Ralph says they were together then, but he falls silent again. The officer nods, trying to help Ralph

find the words by citing a book called The Coral Island. Ralph briefly pictures the glamour that had once surrounded the

beaches, but this island was burnt up like dead wood. He thinks how Simon is dead. Ralph is overcome by sorrow and

cries in great spasms that shake his body. The other little boys begin to cry too. Ralph weeps "for the end of innocence,

the darkness of a man's heart, and the fall through the air of the true, wise, friend called Piggy." The officer is