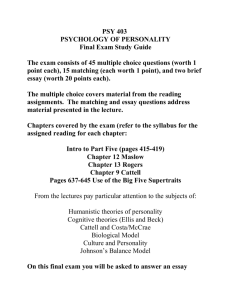

1 PERSONALITY ASSESMENT: A THEORETICAL

advertisement

1 PERSONALITY ASSESMENT: A THEORETICALMETHODOLOGICAL ALTERNATIVE José Manuel Hernández López1 José Santacreu Mas Víctor J. Rubio Franco Abstract This paper presents an alternative to conventional personality assessment. Paraphrasing Carlson, it recovers the role of the person in personality psychology. This paper proposes the concept of interactive style, taken as the individual, idiosyncratic, consistent and stable way a person interacts with situations, as the key aspect in personality study. Objective tests, such as Cattell’s T-data, are considered suitable in personality assessment in opposition to the primacy of self-report. They get around the difficulties of observational techniques in natural settings. Also discussed are the theory and method of designing and implementing computer-based objective tests. Some examples show the usefulness of this type strategy. 1. Taking up an old issue again A few years ago, Carlson (1971) asked where the person was in personality studies. Carlson posed this question as the result of the so-called "disembarkation" of social psychology in personality psychology (Sechrest, 1976; McAdams, 1997) that shifted the interest of personality psychology from the person, considered globally, towards personal variables or specific constructs. In his meta-analytic work, Carlson studied the key words of the 226 articles published in 1968 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. He found that most of the papers studied variables or constructs that, although relevant inasmuch as they occurred in people, stole the limelight from the person taken as an integral whole on the stage of personality psychology. Carlson posed the question again a few years later, finding fairly similar results (Carlson, 1984). In his opinion, personality research had still not “recovered” the person. 1 Department of Biological Psychology and Health. Faculty of Psychology. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Campus de Cantoblanco. 28049. Madrid. E.Mail: josemanuel.hernandez@uam.es 2 Many of us fear that our science has still not recovered the person in spite of a significant change in the overall situation. Many authors feel that personality psychology has moved on from the crisis of the ’70s and ’80s to a “rebirth” in the ’90s (for example, Revelle, 1995; Sperry, 1995; Caprara, 1996; Pervin, 1996 and McAdams, 1997). However, this rebirth does not imply the recovery of the person; rather it stresses the notion of the group as a fundamental element of distinction. Consider the five-factors model, in which the person is important as representing a group and is in a specific place in relation to the members of that group. This boils down to a subject prototype that, by definition, does not exist in reality. By adopting the correlational focus with its unquestionable advantages, we risk “overlooking” the person’s relevance as an individual and not just a part of the sample. This does not necessarily imply an idiographic stance. We could think that personality functions with regularities and is specific to each individual. We could start with the individual and move up to the general (as Kelly did) or from the general down to the individual (as proposed by the inductivehypothetic-deductive spiral formulated by Cattell, 1966, 1988). Nonetheless, the person develops and therefore, behaves, not in a void, but rather by dealing with the conditions in the medium in which the person exists. Behavior and the context are related in terms of reciprocal interaction (Overton and Reese, 1973; Bandura, 1978). In these terms, the relevant element for the study of personality is the consistent and stable behavior determined by an individual’s interaction with a specific situation. This interaction is personal and idiosyncratic, constituting a style of interaction or an interactive style. Determined by the individual’s history, this style is the basis of this consistent, stable behavior. With this in mind, a theory of personality should take three fundamental elements into account. Firstly, it must propose a general form of the individual’s functioning that places the theory of personality within behavioral theory. From this perspective, reference to behavioral assessment seems unavoidable. Traditionally, psychological assessment assumes a mechanistic model where the individual is the owner and has the last word on behavior and this, in turn, is the effect of a combination of internal and external causes. This model suggests that behavior belongs to the individual and is characterized by a basic or common component. This common component is determined by consistency and stability, understood as defining elements of personality. The morphological description of behavior has ended up classifying it in two large types: observable motor behavior (action) and hidden cognitive behavior, understood as referential or symbolic (thought and language). In 3 some cases, however, thought has been understood as an alternative to behavior or a type of phenomenon that can not be classified as behavior. Secondly, a theory of personality must establish a situational taxonomy to accommodate this way of functioning. This means describing of a complete model of its ecosystem, classifying and defining its relevant variables and limiting any research that is not based on the psychological model of functioning. One of these relevant variables is the individual’s perception of this environment, that is, the psychological significance of the situations. This can already be understood as a clear product of interaction given that, to be able to perceive a situation, you need both a situation to perceive and a subject to perceive it. This representation of the environment as this interactive effect is also a cause of the behavior and frees the subject from the purely reactive role of a physicalist approach. Lastly, the theory must delimit the various peculiar modes individuals have of interacting with the situations that they habitually have to face and that, to a certain extent, are determined by their past ways of proceeding in this interaction and that constitute the individual’s personal interaction style. The procedure for gathering information about these elements must not be methodologically restricted from the start. Restricting personality assessment to only using personality self-reports deserves further comment. 2. The “monopoly” of the self-report in personality assessment One of the fundamental criticisms from many points of view of traditional pencil-and-paper personality assessment tests is the difference between what the individual says and what the individual actually does, and the inferential leap to get from this to the description of what the individual is. This brings us back to the age-old problem of the difference between attitude and behavior. Behavioral assessment has highlighted the traditional criticisms of self-reports, mainly the biases originating with the testees—the simulation of responses, social desirability (Edwards, 1957) and the search for response tendencies (Cronbach, 1946, 1950)2. Psychometrics has only partly solved this with sincerity scales and by altering the direction of the scale. However, it can be assumed that, from a differentialist perspective of personality, this form of assessment does discriminate individuals in certain variables (those assessed). Functionally speaking, these solutions seem efficient but probably insufficient. 2 See the revision by Fernández-Ballesteros (1983, 1991). 4 The design of personality assessment self-reports uses the concept of reliability to guarantee quality. Reliability appeals to temporal and internal consistency. Temporal consistency (test-retest reliability) reviews the similarity of the scores obtained by applying the self-report at two different points in time while internal consistency reflects the coherence of the items that make up the scale, concluding that all of them contribute proportionally to the overall score of the evaluated dimension. In both cases, the referent is the evaluation instrument itself while the individuals are representatives of the group that allows these calculations to be made. Although we could establish a parallelism between temporary consistency and internal consistency with stability and behavioral consistency respectively, this parallelism could create confusion. In terms of personality theory, both stability and consistency allude to the individual and not to the assessment instrument. An individual may show behavioral stability and consistency independently of the quality of the assessment instrument in terms of classical test theory. In other words, appealing to the technical guarantees of a personality assessment self-report begs the issue of the peculiarity of an individual’s behavior. Therefore, the coherence of the “items” that make up a scale must not be confused with transituational consistency of behavior, or test-retest reliability with behavioral stability. A self-report assessment of a given personality construct puts the individuals who answer it “in situation” through a series of elements that arise from the rational and/or theoretical and/or empirical analysis of this construct depending on the strategy that created it. The logic of these instruments indicates that all the small portions into which the construct has been dissected (the elements of the self-report) contribute to its quantitative determination and therefore, should fulfill two requirements: one, be highly interrelated; and two, be highly related to the final scoring of the construct. If one of these elements fails to meet either of these requirements, it may be eliminated from the final configuration of the self-report. This procedure purges items from the assessment scale. The hypothesis on which the analysis of internal consistency (like Cronbach’s α ) is based is that the responses to each of the elements of the scale should be similar since all of them are necessary to discriminate the construct to be measured. Therefore, if consistency is detected, it must be due to the elements of the scale and not to the people considered individually, because the individual becomes meaningless when not related to the group. Given the supposition or the premise that individuals are “behaviorally” consistent, if the results obtained do not reflect this consistency, the conclusion is that the scale is poorly created. 5 Another important element of self-report assessment is the limited focus on the behavioral sequence because it emphasizes the final result. So, the individual’s response to the question is what is significant and not so much the base behaviors that manifest this response. Consider, for example, a person who answers, “I always has difficulty in striking up a conversation with strangers” on a typical introversion scale. From the point of view of personality, knowing how this result is manifested is what is relevant. So, it is not the same if this person “avoids” interaction with strangers or if they simply do not have the opportunity to mix with them more than sporadically or if, without being able to avoid the situation, this individual has difficulties. The self-report assessment format precludes making these types of distinctions. This brings use to consider the situation and the relation that the person has to the situation as a necessary element in proper personality assessment. So, the individual, in a given situation will interact in a concrete, specific, unique and personal way with this situation, which constitutes an interactive style. 3. Interactive styles Emphasizing the conjunction of interaction and the behavioral study of human personality, Ribes (1990) bases the study of personality on the inter-behaviorism of Kantor (1959). He considers that personality: a) describes an interactive idiosyncratic manner, b) configured historically c) by the individual’s past, meaning that you can predict particular interactive tendencies in certain conditions. These characteristics imply that personality is a variable or a dispositional factor that belongs to the individual and operates interactively and idiosyncratically. He proposes interactive style as a central element in personality study as a dispositional term of the individual and defines it as the tendency of individuals to behave in a certain way in a specific situation. Furthermore, the manifestation of an interactive style will depend, on one hand, on other dispositional terms: competence or functional correspondence between response morphologies and objects to produce specific results and reason, choice, or preference for certain situations, contingencies, or objects, before interacting with them. In plain English, the subject wants to establish this interaction. On the other hand, it will depend 6 on the characteristics of the situation described in terms of the generic contingencies that configure it. By way of example, imagine posing a problem like this: 6 2 -----and asking for a solution (with the instructions: correctly solve this operation). Without complicating things further, there are four possible answers: 8, 4, 12, 3. The choice of one of these will be determined by ability (the individual has a behavioral repertory with which to respond), the desire or the need to do so (motive) and the individual's history of past interactions (interactive style). For example, in this situation of open contingencies, one could answer “8” because the sum of the operation is the first that comes to mind. One may only know how to add. In this case, ability would determine the answer, not interactive style. In turn, the motive can be manipulated. For example, you could add an instruction: “if you answer correctly you will receive a prize" or “if you don’t answer correctly you will be punished.” If we close the situational contingency and pose this other task: 6 x2 -----there would only be one possible correct and, therefore, reinforceable answer: 12. To respond, the individual uses abilities and reason, but not interactive style since the situation only demands an efficient functional response, which implies multiplying. From the example, we can conclude that an interactive style will be identifiable and measurable if it is stable and consistent in a situation in which the subject can not learn which response will obtain a positive consequence. These are the situations that present open contingencies in which no possible behavior is more reinforced than another. If reinforcement were contingent to a given response, the frequency of this reinforced response would increase and this would not allow for the expected interactive style to manifest itself. Ribes points out two necessary conditions for assessing interactive styles. First, you need to represent contingent situations that require non-specific forms of interaction, that is, you must evaluate in open-contingency 7 situations in which no responses are more reinforced than others. Secondly, situations must be socially neutral inasmuch as the condition with which an individual interacts does not involve the behavior of another individual. In other words, he feels that interactive styles can not be assessed in social interaction situations. In spite of its lack of empirical support, studies of one of these styles (tendency towards risk) show individual differences in experimental situations with open contingencies (Ribes and Sánchez, 1992) and confirm the behavioral consistencies by means of intra-subject analysis (Santacreu, Froján and Santé, 1997; Santacreu, Santé and López-Vergara, in press). However, it is not easy to know which interactive styles would be relevant in personality study. In principle, we do not have an independent theory that identifies these interactive styles. But, in principle, classic personality dimensions do not have one either. Introversion and neuroticism do not exist by themselves outside the behaviors they describe. We do not have conclusive information (not even Eysenck’s) that neuroticism exists beyond a doubt. We simply know that certain behaviors that appear in a sample of individuals are closely related. Observational methods are the golden rule for measuring individuals. However, observing behavior requires defining not only what is going to be observed, but also where and when, which determines the interactive nature of what needs to be observed. If interactive styles reveal themselves when the individual has to cope in specific situations, sets of these functionallyinterrelated specific situations can give rise to manifestations of similar interactive styles. This leads us to an empirical strategy to define the situations that should be identified by other functionally similar situations from which to create the tests. So, the analysis of the prior situation that the assessment demands (its purpose) justifies the use of certain evaluative tasks and not others and delimits the interactive style to be assessed. 4. Gathering T-data This discussion points to the need to base personality study on behavior and break the “monopoly” of self-reports in personality assessment. To put it in Cattellian terms, tests that provide T-data could assess this behavior. T-data come from objective tests, understood as a procedure for obtaining an individual score based on responses to a series of stimuli without the individual knowing the correct response and being unable to modify the response in a given direction (Hundleby, 1973). So, the purpose 8 of the test must be hidden from the subject. This means the individual must be given a convincing reason for the test. This implies asking the person to execute a task, which implies a substantial change in personality assessment. Subjects “do”; they do not “say.” Cattell and Warburton (1967) proposed over 200 action or performance tests, hypothesizing the need for a wide range of short-duration tests (no more than 5 minutes), which could include several different methods during one assessment session. They considered four variable dimensions in the construction of these tests: a) Instructions: they found that minor changes to instructions could cause substantial changes to individuals’ performance. b) Location and materials used: definition of the test conditions. c) Response form: for example a simple response compared to a repetitive response. d) Score: its coding for later analysis Growth in computer technology and its increased use in psychological assessment and diagnosis has made the task of designing such tests easier in the last thirty years. This increases the viability of designing objective assessment tests that measure certain personality traits (particular ways in which an individual interacts with a task) without resorting to self-reporting. Being able to combine various tasks makes it easier to design these tests than in Cattell’s time. Moreover, this probably makes for more precise formulation of the tasks and increases accuracy of the control of the variables as well as of the recording, coding and analysis of the data obtained. 5. Conditions for creating objective tests for personality assessment. The task is to create tests that provide objective data to quantify an interactive or peculiar behavior, determined to some extent by the individual’s learning history. In these tests the individual must deal with a situation or a set of contingencies. This all means considering a series of premises: ♦ Since the idea is to assess an individual who will be taking the test with a certain level of competence and motivation, the results of the test to be created must not be contaminated by these variables. If the test is complex, performance might be affected by the individual’s ability or competence. The immediate consequence of this risk is the creation of 9 minimum difficulty tasks that do not involve any specific ability. In other words, any individual must be able to solve the tasks. Likewise, the person assessed must be sufficiently motivated to undertake the task. This implies being able to control the situation so that the person does indeed complete the task. For example, a job interview could guarantee this level of motivation (in this case, supposedly quite a high level). Experimental situations in which individuals participate voluntarily might not guarantee such motivation. In conclusion, the test design must ensure that the subject has the will and the ability to complete the task. ♦ The test design must consider the situation and contingencies that we can control. This brings us to reflect on the contingencies that, from this perspective, we could manipulate to help the subject interact with the test. In theory, the best way to do this would be to observe and quantify the individual’s behavior in his or her natural context, facing a varied range of open contingencies (even selecting the situations, contexts and settings—the motive in Ribes’ terms—would be a relevant indicator). However, this could make the task impossible to approach. Without getting into philosophical digressions about the concept of liberty, methodologically speaking, the individual’s freedom must be restricted to study the subject’s personality. That is to say, the subject must face situations in which possible behaviors (behavioral sequences) are not predetermined in one direction, but are limited to a finite (and not overly extensive) number, previously considered by the researcher. For example, we can predict and therefore quantify the various ways of putting together a puzzle. Social psychology gives us several examples such as the tasks derived from the well-known “prisoner’s dilemma.” The method can relegate the classic terms of test management theory (reliability and validity) to a secondary level of importance and emphasize other terms that are very close to personality theory: consistency (permanence of the interactive style across various tasks of the same nature, displaying functionally efficient behavior) and stability (permanence of the interactive style at different application times). This leads us to stipulate three tasks: ♦ There must be a consensus about the suitability of the concept (what we want to measure) and the operational definition of the response to the task or situation. For example, if the purpose were to evaluate an interactive style called risk tendency, the consensus would imply an 10 explicit agreement as to the possibility of measuring this style by examining the individual’s behavior in a computer-simulated task. This could involve an individual urgently needing to cross a street during heavy traffic conditions. In this context, a person who crosses without checking the traffic would display riskier behavior than someone who takes more precautions. ♦ Once a consensus is reached, the next step consists in defining tasks that will keep contingencies open, that is, tasks that allow “freedom”, as mentioned previously, but restricting that freedom in carrying out the task in such a way that the subject is not directed by the conditions of the task itself. In other words, it is assumed theoretically that an individual may behave in a consistent, stable, and idiosyncratic way, but that such behavior can only be reflected in situations of open contingencies, since, otherwise, the subject would try to meet the “closed” contingencies of the context or behavioral field. Ribes (1990) uses two strategies to open the contingencies: reducing the test instructions as much as possible and presenting numerous trials that make the relationship between contingencies clear. However, fewer instructions should not imply a loss of precision and clarity. Put another way, the instructions should not allow any ambiguity that makes the performance of the task more difficult. Another important aspect is the absence of any feedback about the subject’s performance and the consequences that arise from this. This reduces the risk of previous trials affecting the subject’s behavior, preventing learning that closes off contingencies. Going back to the previous example of crossing a road in the shortest time possible to evaluate risk tendency (Santacreu and Rubio, 1998), the subject can decide where and when to cross. The instructions only state that the subject must cross the road in the shortest time possible, and the person can move the simulated pedestrian before making it cross. The further the subject moves the “figure” to the left on the screen, the better the view of traffic will be, but the longer it will take to cross. Once the subject decides to cross, there will be no feedback about the result (in other words, the subject will not know whether the “figure” has been run over or not). In short, two variables will define the final result. On one hand, the individual’s style, which influences the strategy adopted, and on the other hand, the characteristics of the situation as interactive elements that “help direct” the path that will be taken in carrying out the task in an interactive style. 11 In principle, we can manipulate three aspects to facilitate the subject’s interaction with the task: a) Test instructions: the idea is for a “natural” strategy to emerge without forcing any other types of determinants. In this sense, the instructions should indicate the nature of the task with no reference to mistakes or time limits. The objective is to leave the maximum number of contingencies open. b) Test format: this must meet two conditions. It must not be excessively complex and it must be possible to complete within the allocated time. c) Feedback: one of Cattell’s T-test characteristics consists in not telling the subject what is being measured. Neither should the subject be given any information about how to perform the task in each situation, not even after the task has been completed. ♦ A third task (or perhaps requirement) is to mask the variable to be evaluated to avoid the individual attributing greater probability to certain responses and thereby not act “freely.” This brings us back to one of the conditions of Cattell’s objective tests Once the test has been constructed, an assessment session will consist of a series of trials. The number will vary depending on the time required to solve each of them. In this respect, Cattell’s criteria that no exercise must take longer than 5 minutes is perfectly appropriate. The result will be a series of repeated scores on tasks presented in successive trials of the operationalized variable. Each of these trials will be a situation (reactive, an assessment element) in which the individual will perform a task (always the same) leading to at least two types of scores—one for each trial and a global score (summary) obtained by adding up or averaging those of each trial. So, different situations at the same time is the same as consistency, but the individual’s consistency and not the test’s. Subsequent assessment sessions applied after the time planned in the research design lapses will contribute stability measures: the same situations at different times. In our example, the person has a maximum of 60 seconds to make a decision to cross the road, and will make 10 discrete attempts. The variable operates with two indicators: the distance moved before crossing and the total time spent crossing. There will be ten different scores for these variables (one for each attempt) and one overall score for the test taken as a whole. One definite advantage is that when we say the same situation we mean this from a functional point of view. The reactives or elements of the 12 test are not exactly the same, but functionally equivalent. This avoids the possible problem of the subject learning the reactives and the possible problems of social desirability or acquiescence if the purpose of the test is sufficiently disguised. This strategy has proved particularly useful in evaluating personality variables in the five-factor model such as conscientiousness (Hernández, Santacreu, Lucía and Shih, 1998). The statistical manipulation of the data obtained will depend on the nature of the variables measured. We can consider the scores of each trial independently and as “contributing” to the overall results (the case of the conscientiousness test mentioned above). Alternatively, we can consider them hierarchically interrelated ( the score of one trial plays a role in interpreting the following one and so on). This would allow us to use accumulated records of the data obtained. A test measuring motivational persistence, for example, would use this analytical strategy. 6. By way of conclusion The paper proposes a commitment to the behavioral study of the personality of human beings. Its antecedents are in the work that authors such as Kantor, Staats, and Ribes have been conducting over the years. As stated in the preceding pages, putting the person back into personality study requires observing individuals in the contexts in which they are behaving. This may seem over ambitious, especially from a methodological point of view. It seems necessary to restrict the object of study. This restriction lies in limiting the individual’s possible behaviors. In other words, limiting such behavior involves restricting the individual’s “free” scope of action. It is only useful to stray into such philosophical and ideologically thorny areas such as freedom if we consider it in either functional or operational terms or both. We simply point out that it is difficult to record the consistencies and stability of behavior that reflect an interactive style in everyday situations where, at least in theory, the possibilities of behavior are, if not unlimited, at least quite numerous,. Two questions about developing the alternative described here remain. One is theoretical and the other has to do with method. The theoretical question refers to delimiting the interactive styles relevant to personality study. However, the strategy should not lead to establishing a “menu” like a general or universal trait structure. In principle there is room to hypothesize that there are as many interactive styles as functionally different situations capable of provoking a response. We do not know how 13 many. Naming these styles requires a consensus among researchers as a starting point. Given that the concept of interactive style alludes to implementing a specific behavioral strategy, it will probably be difficult to label these styles without using more or less global descriptions, which may or may not parallel traditional traits. For example, “performing a task in an ordered and organized manner following a systematic pattern” may well correspond to some facets of the conscientiousness dimension of the fivefactor model. As we have stated, this will not always be possible. The methodological matter is linked to the foregoing. What remains to be done is to design “controlled” situations (in the sense of “limiting” possible behaviors) in which the individual has to perform a given task. It is understood that the interactive style will come into play in functionally identical situations (those which require the same behavioral strategy), although they are morphologically different, since we are not talking about the same situation. In short, to evaluate distinct interactive styles, there must be functionally distinct situations. To achieve sufficient behavioral examples of an interactive style, however, we must observe the behavior of the individual in functionally identical yet morphologically different situations. For example, interactive style “A” would manifest itself in situations “a1, a2,…an” and “B” in situations “b1, b2,…bn”, where “a” and “b” would represent the functional equivalent, while “1,2,…n” would indicate the morphological differences among them. One last aspect to consider is the relevance of a study of these characteristics that allows assessing the personality of individuals while avoiding the possible bias arising from the subject answering questions on a self-report. All this constitutes an interesting challenge that we are willing to go on accepting. 7. References • Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33, 344-358. • Caprara, G.V. (1996). Structures and processes in personality psychology. European Psychologist, 1, 14-26. • Carlson, R. (1971). Where is the person in personality research? Psychological Bulletin, 75, 203-219. • Carlson, R. (1984). What's social about social psychology? Where's the person in personality research? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1304-1309. • Cattell, R.B. (1966). Psychological theory and scientific method. In R.B. Cattell (Ed.). Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. Skokie, Ill.: Rand McNallly. 14 • Cattell, R.B. (1988). The principles of experimental design and analysis in relation to theory building. In J.R. Nesselroade y R.B. Cattell (Eds.). Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. New York: Plenum Press. • Cattell, R.B. y Warburton, E.W. (1967). Objective Personality and Motivation Tests. Urbana, Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. • Cronbach, L.J. (1946). Response sets and test validity. Educational Psychology Measurement, 6, 475-494. • Cronbach, L.J. (1950). Further evidence on response sets and test validity. Educational Psychology Measurement, 10, 3-31. • Edwards, A.L. (1957). The Social Desirability Variable in Personality Research. New York: Dryden Press. • Fernández-Ballesteros, R. (1983). Los autoinformes. In R. Fernández-Ballesteros (Ed.). Psicodiagnóstico. Madrid: UNED. • Fernández-Ballesteros, R. (1991). Anatomía de los autoinformes. Evaluación Psicológica/Psychological Assessment, 7, 263-291. • Hernández, J.M., Santacreu, J., Lucía, B. and Shih, P. (1998). Construcción de una prueba objetiva para la evaluación de la minuciosidad. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (informe de investigación). • Hundleby, J.D. (1973). The measurement of personality by objective tests. In P. Kline (Ed.) New Approaches in Psychological Measurement. New York: Wiley. • Kantor, J.R. (1959). Interbehavioral Psychology. Chicago: Principia Press. (Spanish translation: Psicología interconductual. México: Trillas. 1978). • McAdams, D.P. (1997). A conceptual history of personality psychology. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson and S. Briggs (Eds.). Handbook of Personality Psychology. San Diego, Ca.: Academic Press • Overton, W.F. and Reese, H.W. (1973). Models of development: methodological implications. In J.R. Nesselroade and H.W. Reese (Eds.). Life-Span Development Psychology: Methodological Issues. New York: Academic Press. • Pervin, L.A. (1996). The Science of Personality. New York: Wiley. (Spanish translation: La Ciencia de la Personalidad. Madrid: McGraw-Hill. 1997). • Revelle, W. (1995). Personality processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 295-328. • Ribes, E. (1990). Problemas Conceptuales en el Análisis del Comportamiento Humano. México: Trillas. • Ribes, E. and Sánchez, S. (1992). Individual behavior consistencies as interactive styles: Their relation to personality. The Psychological Record, 42, 369-387. • Santacreu, J., Froján, M.X. and Santé, L. (1997). Risk-Taking Device Test (R.T.D.T.): A New Measurement Device for Risk-Taking. Trabajo de investigación no publicado. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. • Santacreu, J. and Rubio, V.J. (1998). Test de Riesgo Asumido al Cruzar. Nº R.P.I.: M70573. • Santacreu, J., Santé, L. and López-Vergara, R. (in press). Evaluación conductual del estilo interactivo: “Tendencia al riesgo.” • Sechrest, L. (1976). Personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 27, 1-27. • Sperry, R. (1995) The future of psycholo gy. American Psychologist, 50, 505-506.