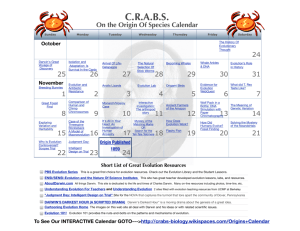

Darwin's conversion: The Beagle

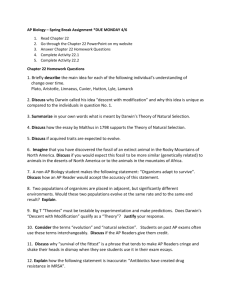

advertisement