Making Bricks Without Straw The NAACP Legal Defense Fund and

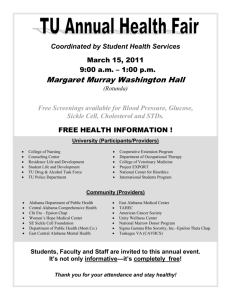

advertisement