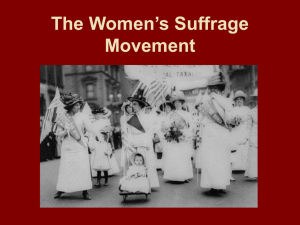

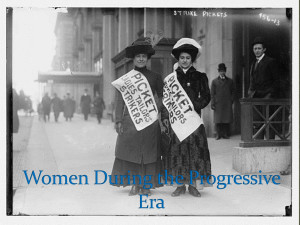

Women's Rights: The Struggle Continues

advertisement