Basel III – What Does It Mean for Core Deposits?

advertisement

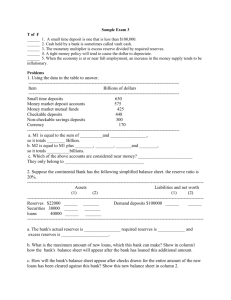

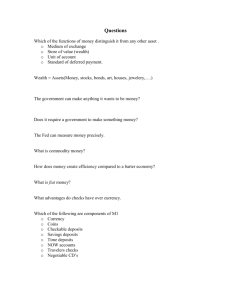

SmartRamps Commentary, March 2012 Basel III – What Does It Mean for Core Deposits? Bank regulation in general and the consistency of bank regulation across countries has been a concern for at least the past twenty-five years. The original Basel Accords in 1988 established recommended minimum capital requirements. Basel II, published in 1994, was an extension of the original recommendations, attempting to extend the original Accords to take into account the growing complexity of financial institutions. Basel II established risk and capital management requirements based on a financial institution’s specific lending and investment holdings. A bank adopting a riskier strategy would be required to hold additional capital to ensure its solvency. Basel II also attempted to reduce differences in regulatory guidance across countries so international banks could not “game” the system. While Basel II was intended to protect the financial sector from the collapse of a major institution, the financial crisis of 2008 suggests that it was not altogether successful in that goal. Thus, Basel III was born. The overall approach recommended in Basel III is much more comprehensive than that of prior accords and can be summarized in five points. 1. Receiving the most publicity, capital standards are both increased and tightened. Tier 1 capital, i.e. common shares and retained earnings, is now emphasized and Tier 3 capital is eliminated. 2. Risk is more closely aligned with the capital framework. For example, banks with greater derivatives risk or greater pro-cyclicality are held to a higher capital standard. 3. A leverage ratio is introduced to restrict the build-up of excessive leverage at a bank. 4. Capital buffers and stress tests are now required (the U.S. implementation of the rules has heavily emphasized stress tests). 5. A minimum liquidity standard is introduced. While Basel III is suggestive only and need not apply to any particular bank in any country, the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank has made it clear that it takes the recommendations of Basel III very seriously. Plus, those rules will apply not only to banks in the U.S. but to any large financial institution, e.g. of more than $50 billion in assets or any institution whose failure would introduce systemic risk to the financial system. Two points about the U.S. application of Basel III have been emphasized in the trade press. First, capital standards have in fact increased. There are concerns that higher capital mandates potentially reduce economic growth, albeit likely by a small amount. Regulators appear willing to accept a small reduction in economic activity to avoid financial crises. Second, in the U.S. the capital standards apply only to a limited set of financial institutions, 2012 McGuire Performance Solutions, Inc. 1 only the largest banks as well as large insurance firms and hedge funds, for example. The vast majority of institutions are not directly covered by the Basel III mandates. Smaller institutions now may have a slight advantage in one regulatory dimension! Core deposits (or non-maturity deposits) were not explicitly covered under the prior Basel Accords. Basel III introduces two features that now cover the role of core deposits, and these are worth reviewing in detail. 1. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) requires that financial institutions hold liquid assets equal to 100% of short term funding needs over a 30 day stress test period. That stress test includes 7.5% of core deposits potentially leaving the institution. In effect, 7.5% of core deposits are required to be matched by high quality liquid assets such as cash or other liquid assets. Each $1 billion in core deposits would require the institution to hold $75 million in liquid assets. LCR is effectively a reserve requirement for core deposits. How does it compare with existing reserve requirements? Since April 1992, the Federal Reserve’s marginal required reserve ratio on transaction oriented core deposits has been 10 percent. Since December 2011 this ratio applies to net deposits exceeding $71 million. That suggests the existing reserve ratio is higher than required by Basel III’s LCR. However, the Federal Reserve has set no reserve requirement for nontransaction core deposits while the LCR applies to those core deposits also. Thus, whether LCR increases or decreases U.S. reserve requirements depends on the (a) size of the financial institution and (b) the mix of deposits between transactions and nontransactions accounts, e.g. between checking and savings accounts. Given the size of nontransactions accounts at most of the larger financial institutions, it would appear that LCR will result in an increase in required reserves. 2. Basel III introduced the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) to measure the amount of stable funding relative to the risk and liquidity of the assets being funded. The sources of stable funding are assigned an “availability factor” used to offset the required stable funding uses that include loans or mortgage backed securities. Tier 1 and 2 capital instruments, e.g. retained earnings, are assigned an availability factor of 100%. Stable retail deposits are assigned an availability factor of 85% and less stable deposits are assigned an availability factor of 70%. Wholesale funding is assigned a 50 percent availability. Other liabilities are assigned zero availability. The impact of the NSFR is that each $1 billion in core deposits potentially reduces capital to fund loans by $850 million. But core deposits are now treated as a source of stable funding, and NSFR make core deposits more desirable in the long term. The implications of Basel III for core deposits are ambiguous. The LCR standard suggests a greater cost associated with core deposits while the NSFR standard suggests a greater benefit. Some large financial institutions may find greater net benefits of core deposits with Basel III while others may find greater costs. The outcome will depend on the mix of 2012 McGuire Performance Solutions, Inc. 2 transaction and nontransaction core deposits and the relative costs of raising additional capital versus generating core deposits and proving their supply stability. In contrast, there may be a net benefit to small institutions, for two reasons. First, large financial institutions likely have a greater cost associated with raising stable core deposits. That cost will yield a potential advantage to smaller institutions in their attraction of stable core deposits. And second, to the extent that the spirit of Basel III is extended to smaller institutions, the NSFR standard makes explicit the role that stable core deposits play in funding. Active analysis and proof of supply stability, as done by MPS Deposit Analysis Service clients for almost 20 years, should lead regulators to a greater appreciation of the value of core deposits. Final Words: The Current Interest Rate Outlook A few words are in order on the current interest rate outlook, following up the commentary of last quarter that interest rates are likely to remain low and stable. From a probabilistic view, that is still the most likely outcome. But recent favorable economic growth news in the U.S. suggests that interest rates may begin to increase sooner rather than later. After years of low short and long term interest rates, and after the Fed’s explicit statement that Operation Twist was intended to reduce long term interest rates, long rates have begun to creep back (although short term interest rates have remained fundamentally unchanged). Is this the start of a long term trend or just the standard volatility of interest rates? Has the Fed interpreted the economic data as indicating the green shoots of real economic recovery and is letting long term rates rise? Or have other economic factors begun to push up long rates even as the Fed continues with relatively expansionary policy? It is far too soon to read anything significant into the increases in long term interest rate, in my opinion. Nonetheless, the recent positive economic news coupled with the gains in long term rates does increase the probability that the economy may be preparing to move into a new rate environment. So keep a close watch on the curve! Richard G. Sheehan, Ph.D. Senior Vice President, Research 2012 McGuire Performance Solutions, Inc. 3