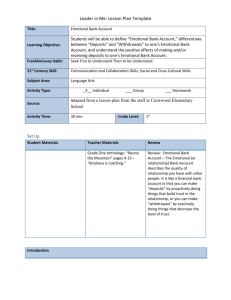

What Really is a Stable Deposit?

advertisement

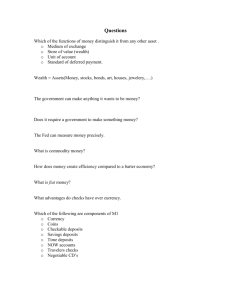

SmartRamps Commentary, June 2012 What Really is a Stable Deposit? Last quarter’s commentary examined the implications of Basel III for core deposits. Two features of the guidance were noted as important. First, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) requires financial institutions subject to Basel III to hold a minimum of 7.5% of their stable deposits in the form of cash or additional equity. One can interpret the LCR as equivalent to a standard reserve requirement for deposits. Second, the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) puts a premium on stable funding sources that can be used in the long term to partly offset required stable funding uses and offset capital requirements. Most financial institutions in the US will not be subject to the provisions of Basel III. Some of them may thus find it tempting to discount its importance. Even if an institution is not subject to the full implementation of Basel III, understanding how the NSFR rule works and its implications for liquidity and capital requirements will be important. In other words, an institution may not be explicitly subject to NSFR but knowing what that regulation implies will allow management to better manage risk. Underlying Basel III is a major unaddressed issue, a terminological issue really, relating to “core deposits,” “nonmaturity deposits,” and “stable funding sources.” From an individual financial institution’s perspective, there are two important questions. First, is there any difference between these three terms? The answer to that is “maybe.” And second, what specific categories of deposits are eligible to fit under the different labels? To answer the first question, nonmaturity deposits are the simplest to define. They include any deposit class that has no contractually stated maturity – balances can be withdrawn1 at any time without penalty. Core deposits are defined a bit more ambiguously. They are types of deposits central to the bank’s deposit-taking mission. Stable funding sources is the most ambiguous – they are not explicitly defined in Basel III at all. Presumably they include any liability whose supply is not expected to adversely change appreciably over time. So what types of US deposits fit under the different labels? Nonmaturity deposits would presumably include checking accounts, savings accounts, and money market accounts, while excluding CDs. Core deposits would presumably include traditional checking accounts and savings accounts without question. The case for ‘hotter money” money market accounts might be open to question, although money market funds were established in 1971 initially as a substitute for checking accounts and money market accounts carry a check writing capability. Stable deposits would presumably include only non-rate value oriented checking and savings accounts that have remained stable over time. 1 Many US nonmaturity deposits except DDA have contractual restrictions on the full withdrawal of funds. These are rarely, if ever imposed, however. 2012 McGuire Performance Solutions, Inc. 1 But the key word in the prior paragraph is presumably. Some institutions will have accounts in checking deposits that vary tremendously; other institutions will have accounts in money market accounts (or even CD’s) that are remarkably stable. The implication is that what type of deposits fall into which Basel III category is not something that can be addressed strictly on theoretical grounds. It must be addressed primarily on empirical grounds. That point needs to be emphasized. Core deposits are nonmaturity deposits, but may or may not be stable funding sources. This is not recognized in the official record - Basel III does not specify the possibility of differences across financial institutions and the Federal Reserve’s proposed implementation focuses on Tier 1 capital rather than on stable funding sources. MPS has examined all types of deposit classes across a wide range of institutions since 1995. We can make three important general statements based on that experience: First, behavior of account types with the same name can vary widely across institutions. For example, the checking category at one institution can have a long-term retention rate of virtually 100 percent for long periods and clearly fit the definition of stable deposits. Yet at another institution, less than 50 percent of checking category balances remain after only five years. The determining factor is likely that service, convenience, and product fit are all excellent at the first institution and poor at the other. Or depositor demographics could be contributing. For money market categories, the range of retention rates is typically even greater and highly correlated with tier size. Second, many institutions have extremely stable core/nonmaturity deposits. It is not atypical to find checking and savings deposits with average lives well into low double digits at Base Case (constant current interest rates). Average lives do tend to shorten, however, as interest rates rise (and vice versa). This must be factored into the stability assessment. Third, the institution’s pricing behavior will have an impact on the stability of their core deposits. If an institution chose to compete on features such as service, convenience, and product fit, rather than on rates paid, changes in interest rates will likely have a limited impact on deposit stability because the financial component of supply motivation is low. In contrast, if an institution competes on rates paid, a change in interest rates may also have a limited impact on deposit stability, but it will have a significant impact on interest expense and possibly earnings. In the former case stability is created while in the latter case it is bought. Surely that distinction needs to be considered in defining stable deposits! While for most US institutions Basel III will not have a direct impact, understanding what defines and drives stable deposits is critical for managing risk and in maximizing earnings. The solution is to quantify historic behaviors – the only guide to noncontractual behaviors in the future – at high levels of accuracy. Statistical methodologies to do this have been proven successful in many applications, across several charter types. Now is the time to consider such a study for your institution. Richard G. Sheehan, Ph.D. Senior Vice President, Research 2012 McGuire Performance Solutions, Inc. 2