Treatment injury case study

advertisement

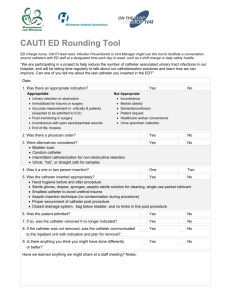

Treatment injury case study August 2011 – Issue 36 Sharing information to enhance patient safety EVENT: Urinary catheterisation INJURY: Urethral damage Case Study Lee, a 68-year-old man, was sent by his GP to the emergency department with acute urinary retention. Lee had a complicated urological history, having developed a urethral stricture many years previously, probably as a result of having contracted a sexually transmitted infection. The stricture had been dilated a number of times and Lee’s condition had been stable for a few years. In the months prior to developing urinary retention, he had been having increasing difficulty with his urine flow. It was not clear if this was due to a recurrence of the stricture. Lee’s GP also suspected benign prostatic hypertrophy. Key points • Urethral strictures most commonly arise owing to instrumentation of the urinary tract, but can also be caused by infections, particularly gonorrhoeal urethritis • It’s important to obtain a history from the patient prior to catheterisation and to consider the possibility of stricture disease • If there is a chance that a stricture is present and the catheter does not advance readily, do not persist with attempts to catheterise • If expert help is not available, a Bonanno type suprapubic catheter should be used • In patients without stricture disease, if a 14 French catheter does not advance with gentle insertion, a larger catheter may be better. A smaller one is likely to curl up in the urethra • Repeated forceful attempts to catheterise can result in the catheter perforating the urethral wall, creating a false passage • Consider the possibility of postobstructive diuresis – monitor at-risk patients for two or three hours after relief of the obstruction. When Lee was seen at the emergency department by one of the junior medical staff he was noted to have a distended bladder. An attempt was made to insert a 14 French indwelling urinary catheter. Inserting the catheter proved extremely difficult and 100ml of blood-stained urine passed in the process. The catheter was removed and another attempt was made using a smaller 12 French catheter. After much effort, the doctor was unable to insert this catheter either, so a urology opinion was sought. When seen by the urology registrar, there was frank blood draining from the urethral meatus. Urethroscopy was carried out using a flexible cystoscope. This revealed a false passage in the penile urethra, most likely caused by the unsuccessful catheterisation attempts. There was also a bulbar urethral stricture proximal to this. The stricture was dilated under direct vision using a balloon dilator. A catheter was successfully inserted into the bladder using a guide wire and further treatment was planned for the stricture. A treatment injury claim was lodged for damage to the urethra as a result of catheterisation. ACC sought external clinical advice from a urologist who advised that, given Lee’s complex history, it had been unwise for the junior medical staff to persist with catheterisation after the first attempt failed. In his opinion urological input should have been sought sooner. ACC accepted the claim for urethral injury but excluded Lee’s underlying urethral stricture from cover. Expert Commentary Andre Westenberg FRACS Urethral stricture disease is a relatively common urological problem. A scar in the urethra blocks the bladder outlet and results in poor flow and secondary bladder irritability. This may lead to urinary retention and, in rare cases, fistulation with the development of a ‘watering can’ perineum (where it becomes riddled with multiple fistulae). We know that strictures have been part of the human condition since ancient times. Silver urethral dilators have Case study been found buried with pharaohs in their tombs. The need for these devices was no doubt due to the prevalence of strictures caused by sexually transmitted infections, particularly gonorrhoea. Gentle urethral catheterisation should be attempted as a first step. If a 14 French catheter does not advance, it is often better to try a larger catheter such as an 18 French rather than a smaller one, as a 12 French catheter is likely to just curl up in the urethra. Whilst gonorrhoeal urethritis is still an important cause of urethral strictures, it is rare. These days, strictures are most often caused by previous instrumentation of the urinary tract, with an incidence of up to five percent after trans-urethral prostate resection. Even relatively trivial urethral trauma, such as an apparently straightforward urethral catheterisation, can result in severe stricture disease. It is important to obtain a history and to consider the possibility of stricture disease. If there is a chance of stricture and the catheter does not advance readily, attempts to catheterise should be abandoned. BXO (balanitis xerotica obliterans), an inflammatory condition of the prepuce and glans, is increasingly recognised as a cause of urethral strictures, and while on occasion strictures are referred to as idiopathic, some specialists believe that ‘idiopathic’ strictures most likely arise from forgotten perineal trauma. In older men, urethral strictures can co-exist with benign prostatic obstruction. Both conditions lead to similar symptoms and they can be difficult to separate on clinical examination only. Stricture should be considered as a possible cause of symptoms in those patients who have a history of transurethral surgery, pelvic trauma or previous catheterisation. Strictures rarely resolve unless patients have a formal urethroplasty. Those patients presenting with obstructive symptoms, who have a history of urethral stricture disease, are likely to have reformed their strictures. Strictures can be diagnosed by the shape of the urinary flow rate curve or by cystoscopy. Most urologists try incising the stricture under anaesthetic as a first step, but the rate of recurrence is unfortunately high. In young, otherwise healthy patients, a formal urethroplasty gives the best chance of long-term success. In older patients with vascular insufficiency, where there may be problems with graft uptake or healing, long-term self-dilation with a urethral catheter is often advised. Temporary thermoalloy expandable stents to hold the stricture open after urethrotomy may be useful in some. Acute urinary retention is exceedingly uncomfortable and can be distressing, not only for the patient but also for the clinician attempting to relieve the obstruction. How ACC can help your patients following treatment injury Many patients may not require assistance following their treatment injury. If expert help is not available, a Bonanno type suprapubic catheter should be used. This is a very safe way to relieve obstruction in those with an obviously palpable bladder. Insert the catheter one centimetre above the symphysis pubis and advance it directly backwards, perpendicular to the abdominal wall, to reduce the incidence of bowel injury. This is a safe technique, even in obese patients. A more acute angle downwards runs the risk of missing the bladder. A bladder scan can be useful in a larger patient in order to confirm that the bladder is full. Repeated forceful attempts to catheterise can result in the catheter perforating the urethral wall and creating a false passage. This not only is uncomfortable but can result in significant bleeding and further stricturing. It can sometimes make it difficult to find the true urethral lumen at future cystoscopy. It is important to consider the possibility of post-obstructive diuresis. If the patient has been in retention for any length of time, they may have physiological renal changes that decrease the ability of the kidneys to concentrate urine. Relief of the obstruction can lead to a fierce diuresis and elderly patients in particular can become significantly dehydrated with electrolyte disturbances. It is important to monitor these patients for two or three hours after the relief of the obstruction to ensure they do not need intravenous support. References Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Urethral Strictures. BJU Int 2011; 107(1):6-26 Jordan GH, Schlossberg SM. Surgery of the penis and urethra. Chpt 33 in: Wein AJ, et al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology vol 1, 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2007:1054-75 Claims information Between 1 July 2005 and 30 June 2011, ACC received 149 claims related to urinary catheterisation. Of these, 129 were accepted. Of the accepted claims, the most common injuries were damage to the urethra and bladder. The most common reason for declining a claim was that there was no physical injury. However, for those who need help and have an accepted ACC claim, a range of assistance is available, depending on the specific nature of the injury and the person’s circumstances. Help may include things like: About this case study • • This case study is based on information amalgamated from a number of claims. The name given to the patient is therefore not a real one. • contributions towards treatment costs weekly compensation for lost income (if there’s an inability to work because of the injury) help at home, with things like housekeeping and childcare. No help can be given until a claim is accepted, so it’s important to lodge a claim for a treatment injury as soon as possible after the incident, with relevant clinical information attached. This will ensure ACC is able to investigate, make a decision and, if covered, help your patient with their recovery. ACC6026 August 2011 ©ACC 2011 Printed in New Zealand on paper sourced from well-managed sustainable forests using oil free, soy-based vegetable inks. The case studies are produced by ACC’s Treatment Injury Centre, to provide health professionals with: • • an overview of the factors leading to treatment injury expert commentary on how similar injuries might be avoided in the future. The case studies are not intended as a guide to treatment injury cover. Send your feedback to: TI.info@acc.co.nz