Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Tourism Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tourman

A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding

and destination image

Hailin Qu a, *, Lisa Hyunjung Kim b,1, Holly Hyunjung Im c, 2

a

William E. Davis Distinguished Chair, School of Hotel and Restaurant Administration, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078, USA

School of Hotel and Restaurant Administration, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078, USA

c

Department of Hotel Management, College of Culture and Tourism, Jeonju University, Republic of Korea

b

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 22 July 2009

Received in revised form

10 March 2010

Accepted 22 March 2010

Despite the significance of destination branding in both academia and industry, literature on its

conceptual development is limited. The current study aims to develop and test a theoretical model of

destination branding, which integrates the concepts of the branding and destination image. The study

suggests unique image as a new component of destination brand associations. It is proposed that the

overall image of the destination (i.e., brand image) is a mediator between its brand associations (i.e.,

cognitive, affective, and unique image components) and tourists’ future behaviors (i.e., intentions to

revisit and recommend). The results confirmed that overall image is influenced by three types of brand

associations and is a critical mediator between brand associations and tourists’ future behaviors. In

addition, unique image had the second largest impact on the overall image formation, following the

cognitive evaluations.

Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Destination branding

Destination image

Brand image

Brand associations

Cognitive image

Affective image

Unique image

Overall image

Loyalty

1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that tourism destinations must be

included in the consumers’ evoked set, from which an ultimate

decision is made (Cai, Feng, & Breiter, 2004; Dana & McClearly,

1995; Leisen, 2001; Tasci & Kozak, 2006). However, consumers

are generally offered various destination choices that provide

similar features such as quality accommodations, beautiful scenic

view, and/or friendly people. Therefore, it is not enough for

a destination to be included in the evoked set; instead the destination needs to be unique and differential to be selected as a final

decision. From this perspective, the concept of destination branding

is critical for a destination to be identified and differentiated from

alternatives in the minds of the target market.

Although not explicitly examined in the context of branding,

destination image should be regarded as a pre-existing concept

corresponding to destination branding (Pike, 2009). In fact, the core

* Corresponding author. Tel.: þ1 405 744 6711; fax: þ1 405 744 6299.

E-mail addresses: h.qu@okstate.edu (H. Qu), hj.kim@okstate.edu (L.H. Kim),

hollyim@jj.ac.kr (H.H. Im).

1

Tel.: þ1 405 744 6711; fax: þ1 405 744 6299.

2

Tel.: þ82 63 220 2553; fax: þ82 63 220 2736.

0261-5177/$ e see front matter Ó 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.014

of destination branding is to build a positive destination image that

identifies and differentiates the destination by selecting a consistent brand element mix (Cai, 2002). The image of a destination

brand can be described as “perceptions about the place as reflected

by the associations held in tourist memory” (Cai, 2002, p. 723).

From the definition an instant question rises: what are these

associations? There is no doubt that many studies rooted from

destination image were conducted to investigate the proposed

destination branding (e.g., Cai, 2002). Unfortunately, however,

there is still paucity in understanding brand associations and image

of a destination brand. This study seeks to understand the nature of

a relationship between these concepts.

Based on the knowledge that destination image is a total

impression of cognitive and affective evaluations (Baloglu, 1996;

Baloglu & Mangaloglu, 2001; Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Hosany,

Ekinci, & Uysal, 2007; Mackay & Fesenmaier, 2000; Stern &

Krakover, 1993; Uysal, Chen, & Williams, 2000), it is suggested

that brand associations should include cognitive and affective

image components (Pike, 2009). These two components are widely

accepted as influential indicators of destination image (Baloglu,

1996; Baloglu & Mangaloglu, 2001; Baloglu & McCleary, 1999;

Hosany et al., 2007; Mackay & Fesenmaier, 2000; Stern &

Krakover, 1993; Uysal et al., 2000).

466

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

This study argues that unique image of a destination needs to be

regarded as an important brand association to influence the image

of a destination brand. Creating a differentiated destination image

has become a basis for survival within a globally competitive

marketplace where various destinations compete intensely. A

strong, unique image is the essence of destination positioning for

its ability to differentiate a destination from competitors to get into

the consumers’ minds, which simplify information continuously

(Botha, Crompton, & Kim, 1999; Buhalis, 2000; Calantone,

Benedetto, Hakam, & Bojanic, 1989; Chon, Weaver, & Kim, 1991;

Crompton, Fakeye, & Lue, 1992; Fan, 2006; Go & Govers, 2000;

Mihalic, 2000; Mykletun, Crotts, & Mykletun, 2001; Uysal et al.,

2000). Consequently, this study proposes that destination branding should emphasize the unique image of a destination, which

exercises a power to differentiate it from competitors. The current

study proposes that unique image should be regarded as a brand

association.

The purpose of this study is to develop and test a theoretical

model of destination branding through adopting both destination

image studies and traditional branding concepts and practices.

Specifically, the current study examines the relationships among

brand associations (i.e., cognitive, affective, and unique image

components), brand image (i.e., overall image of a destination), and

tourists’ future behaviors. For this purpose, an empirical test was

conducted in the state of Oklahoma, in which successful destination

branding is necessary to overcome its lack of clear destination

image.

Oklahoma was once considered the land of opportunity because

of the oil industry from the 1890s through the 1920s. People came

from all parts of the world to seek their fortunes in Oklahoma’s

teeming oil fields (Kurt, 1999). Several decades later, however, the

perception of the state’s history became deteriorated and the

tourism industry is still battling an image rooted in the State’s 100year history. The basic perception of Oklahoma is that it is flat,

dusty, and windblown (Kurt, 1999). The state’s tourism promoters

have begun to recognize the important role of the image of Oklahoma in boosting the state’s tourism industry. This has driven the

state to launch and implement the $4 million “Oklahoma Native

America” advertising campaign to increase awareness of Oklahoma

as a travel destination in the minds of visitors (Oklahoma Tourism

and Recreation Department, 2003). However, Oklahoma Tourism

and Recreation Department (OTRD, 2006) reported that only 47% of

respondents were interested in the state of Oklahoma as a tourist

destination. In addition, 39% of those who are uninterested in

Oklahoma admitted that they do not know much about the state.

These results clearly show that the state of Oklahoma is lacking

a strong, positive, and unique destination image in the minds of

potential tourists. Thus, it is critical to identify the image of the

state of Oklahoma and propose the appropriate destination

branding strategy.

The current study focuses on developing and testing a theoretical model of destination branding, as well as exploring the

potential of the State of Oklahoma as a preferred destination brand.

Specifically, the study tries to fill the gap in the literature in three

ways. First, the study aims to incorporate the existing concepts of

branding with destination image studies. This study identifies the

conceptual similarities between the components of destination

image and brand association in the marketing literature, and

suggests different types of destination image (i.e., cognitive, affective, and unique images) as three types of brand associations in

destination branding. Second, the study brings new focus on

unique image. It has been argued as an important dimension of

destination image (Echtner and Ritchie, 1993), yet less recognized

by destination branding scholars. This study theoretically includes

unique image as one type of destination brand associations, and

empirically tests its significance on destination branding. Last, the

study provides a practical insight into Oklahoma as a destination

brand.

2. Literature review

2.1. Destination branding

Destination branding can be defined as a way to communicate

a destination’s unique identity by differentiating a destination from

its competitors (Morrison & Anderson, 2002). Similar to the general

knowledge on brands, destination brands exert two important

functions: identification and differentiation. In the branding literature, the meaning of “identification” involves the explication of

the source of the product to consumers. While a product in general

terms represents a physical offering, which can be easily modified,

a place as a product is a large entity which contains various material

and non-material elements to represent it (Florek, 2005). For

example, a place includes tangible attributes such as historical sites

or beaches as well as intangible characteristics such as culture,

customs, and history. Because of the complex nature of a destination to be a brand, generalization of the identity is inevitable. Brand

identity is critical for generalization of desirable characteristics

projected by supplier’s perspective. It explains the expectations of

a supplier about how a brand should be perceived by its target

market. Defining a target market is crucial because some aspects of

a destination may seem positive to one segment while ineffective to

another (Fan, 2006). Based on the projected brand identity,

consumers should develop a relationship with a particular brand by

generating a value proposition either involving benefits or giving

credibility to a particular brand (Aaker, 1996; Konecnik & Go, 2008).

In addition to the function of identification, a destination brand

differentiates itself from its competitors based on its special

meaning and attachment given by consumers. Generally, tourism

destinations emphasize points of parity associations such as high

quality accommodations, good restaurants, and/or well-designed

public spaces (Baker, 2007, p. 101). It is more critical to understand

what associations of a brand are advantageous over competitors

(i.e., points of difference). Points of difference associations help

consumers positively evaluate the brand and attach to the brand

(Keller, 2008, p. 107). In fact, the key to branding is that consumers

perceive a difference among brands in a product category (i.e.,

positioning); because a brand perceived distinctive and unique is

hard to be replaced by other brands.

2.2. Brand identity and image

Previous studies argue that brand identity and brand image are

critical ingredients for a successful destination brand (Cai, 2002;

Florek, Insch, & Gnoth, 2006; Nandan, 2005). The confusion exists

as to the difference between the two concepts. One of the significant points of differentiation is that they are generated based on

two different perspectives; the sender’s and the receiver’s (Florek

et al., 2006). In short, identity is created by the sender whereas

image is perceived by the receiver (Kapferer, 1997, p. 32).

Brand identity reflects the contribution of all brand elements to

awareness and image (Keller, 1998, p. 166). It provides a direction,

purpose, and meaning for the brand and is central to a brand’s

strategic vision and the driver of brand associations (Aaker, 1996).

On the other hand, brand image can be defined as consumer

perceptions of a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in

consumer’s memory (Keller, 2008). To brand a destination, the

sender (i.e., destination marketers) projects a destination brand

identity through all the features and activities that differentiate the

destination from other competing destinations. All the while, the

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

receiver (i.e., a consumer) perceives the image of the place, which is

formed and stored in their minds (Florek et al., 2006).

It should be noted that the relationship between destination

brand identity and brand image is reciprocal. Brand image plays

a significant role in building brand identity (Cai, 2002), whereas

brand image is also a reflection of brand identity (Florek et al.,

2006). That is, consumers build a destination image in their

minds based on the brand identity projected by the destination

marketers. Then, destination marketers establish and enhance

brand identity based on their knowledge about consumer’s brand

image on the particular destination. Thus, destination image is

critical to create the positive and recognizable brand identity.

Positive brand image is achievable through emphasizing strong,

favorable, and unique brand associations. That is, consumers

perceive positive brand image when brand associations are

implemented to suggest benefits of purchasing from the specific

brand. This then creates favorable feelings toward the brand, and

differentiates it from alternatives with its unique image.

2.3. Brand associations

Brand associations influence consumer evaluations toward the

brand and brand choice (i.e., intentions to visit or purchase) (Aaker,

1991, 1996; Keller, 1993, 1998; Low & Lamb, 2000; Woodside &

Lysonski, 1989; Um & Crompton, 1990). In the branding literature,

brand associations are classified into three major categories: attributes, benefits, and attitudes (Keller, 1993, 1998). According to

Keller (1993, 1998), attributes are those descriptive features that

characterize a brand. In other words, an attribute is what

a consumer thinks the brand is or has to offer and what is involved

with its purchase or consumption. The benefits that may occur are

the personal value consumers associate with the brand attributes in

the form of functional, symbolic, experiential attachments. That is,

what consumers think the brand can do for them. Brand attitudes

are consumers’ overall evaluations of the brand and are the basis

for consumer behavior (e.g., brand choice).

The image of a place is also an important asset (Ryan & Gu,

2008). Ryan and Gu (2008) emphasize that the image itself is

the beginning point of tourist’s expectation, which is eventually

a determinant of tourist behaviors. In addition, the authors

explained that destination image exerts two important roles for

both suppliers and tourists. The first role involves informing the

supply systems of what to promote, how to promote, who to

promote to and, for the actual product that is purchased, how to

design that product. The second role involves informing the

tourist as to what to purchase, to what extent that purchase is

consistent with needs and self-image, and how to behave and

consume (p. 399).

In the tourism literature, it is widely acknowledged that overall

image of a destination is influenced by cognitive and affective

evaluations (Baloglu, 1996; Baloglu & Mangaloglu, 2001; Baloglu &

McCleary, 1999; Hosany et al., 2007; Mackay & Fesenmaier, 2000;

Stern & Krakover, 1993; Uysal et al., 2000). Cognitive evaluation

refers to beliefs and knowledge about an object whereas affective

evaluation refers to feelings about the object (Baloglu & Brinberg,

1997; Gartner, 1993; Walmsley & Jenkins, 1993; Ward & Russel,

1981). Unfortunately, the majority of image studies treated destination image as a cognitive evaluation. Only few studies employed

both cognitive and affective components in understanding the

overall image of a destination (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Hosany

et al., 2007; Mackay & Fesenmaier, 2000; Uysal et al., 2000).

It is important to consider both cognitive and affective components of destination image to build a comprehensive destination

branding model. Acclaiming Gartner’s (1993) Image Formation

Process as the most comprehensive model toward a destination

467

branding, Cai (2002) pointed out the compatibility of Gartner’s

(1993) Image Formation Process and Keller’s (1998) types of

brand association. The author argues that Gartner’s cognitive and

affective image components are conceptually parallel with Keller’s

attribute and benefit brand associations. Pike (2009) further

supports the notion that brand associations in destination branding

should include cognitive and affective image components. Thus,

this study suggests that the brand image of a particular destination

is influenced by the cognitive and affective associations stored in

the consumers’ minds. This rationale is supported by two premises;

(1) the acceptance of destination image as a result of cognitive and

affective evaluations in the tourism literature, and (2) the conceptual similarities of cognitive and affective evaluations between

destination image formation and types of brand association in the

branding literature.

In terms of destination branding, Cai (2002) claims that attitudes may be one type of brand association for building destination

image. However, there is still conceptual confusion between attitudes and destination image (Sussman and Ünel, 1999). Destination

image is also viewed as an attitudinal construct consisted of

cognitive and affective evaluations (Baloglu & McCleary, 1999). For

their conceptual closeness, this study takes the side of Baloglu and

McCleary’s standpoint.

Although it is argued that cognitive and affective image

components are hierarchically correlated to form a destination

image (Cai, 2002, Gartner, 1993, Woodside & Lysonski, 1989), it is

still possible that each cognitive and affective brand image

component would have unique contributions to the overall image

formation. That is, each association would have a different level of

impact on the overall image formation because brand associations

are not considered equally weighted in terms of performance to

consumers (Keller, 2008, p. 59). The separate treatment of cognitive

and affective components is necessary to examine their unique

effects on consumers’ attitude structure and future behaviors

(Baloglu & Brinberg, 1997; Russel, 1980; Russel & Pratt, 1980; Russel

& Snodgrass, 1987; Russel, Ward, & Pratt, 1981). Consequently, this

study proposes that positive cognitive and affective components as

separate and independent brand associations would be positively

related to the overall image of a destination (i.e., brand image).

Thus, hypothesis 1 and 2 are established as:

H1: Cognitive image will positively affect the visitor's overall

image of a destination.

H2: Affective image will positively affect the visitor's overall image

of a destination.

The current study examines the cognitive and affective image

components of brand associations that influence brand image (i.e.,

destination image). It is proposed that there is an additional image

component to be considered as a brand association: unique image.

Contrary to common image, unique image is highlighted as

a construct that envisages the overall image of a destination

(Echtner & Ritchie, 1993). According to Echtner and Ritchie (1993),

the overall image of a destination should be viewed and measured

based on three dimensions of attributes: holistic, functionalpsychological, and unique-common characteristics. Uniqueness is

particularly important due to its influence on differentiation among

similar destinations in the target consumers’ minds (Cai, 2002;

Echtner & Ritchie, 1993; Morrison & Anderson, 2002; Ritchie &

Ritchie, 1998). One of the purposes of branding is to differentiate

its product from those of competitors (Aaker, 1991, p. 7). Similarly,

destination branding should emphasize a destination’s unique

image to be differentiated from competing destinations by

consumers. In fact, destination branding is partly defined as a way

to communicate the expectations of a satisfactory travel experience

468

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

that is uniquely associated with the particular destination (italics

added) (Blain, Levy, & Ritchie, 2005; Pike, 2009). Uniqueness

provides a compelling reason why travelers should select a particular destination over alternatives. Positive brand image is partly

achieved through the uniqueness of brand associations to the brand

in memory (Keller, 2008, p. 56). Thus, the unique image of a destination is critical to establish the overall image in the consumers’

minds. A strong, unique image would increase the favorability of

the overall image toward the destination. Therefore, it is deduced

that:

destination (Kozak & Rimmington, 2000; Oppermann, 2000;

Weaver & Lawton, 2002; Yvette & Turner, 2002). It is argued that

a person with a perceived positive image is more likely to recommend the destination (Bigné et al., 2001). Thus, it is expected that

a visitor with positive overall image, as a total impression of

cognitive, affective, and unique images, would be more likely to

revisit the destination and recommend it to others. That is, overall

image would mediate the relationships between destination brand

image and tourist behavior in destination selection. Therefore, it is

hypothesized that:

H3: Unique image will positively affect the visitor's overall

image of a destination.

H4: Visitor's perception of overall image toward a destination will

mediate the relationships between three destination brand

images (cognitive, affective, and unique images) and the visitor's intention to revisit the destination.

H5: Visitor's perception of overall image toward a destination will

mediate the relationships between three destination brand

images (cognitive, affective, and unique images) and the visitor's intention to recommend the destination to others.

2.4. Tourist behaviors

It has been supported that the overall image of the destination is

influential not only on the destination selection process but also on

tourist behaviors in general (Ashworth & Goodall, 1988; Bigné,

Sánchez, & Sánchez, 2001; Cooper et al., 1993; Mansfeld, 1992).

The intentions to revisit the destination and to spread a positive

word-of-mouth have been the two most important behavioral

consequences in destination image and post-consumption

behavior studies.

The intention to revisit has been extensively studied in tourism

research for its signal of customer loyalty. In the marketing discipline, the concept of customer retention has been widely emphasized because attracting new customers is more expensive than

retaining existing customers (Rosenberg & Czepiel, 1984). Previous

studies supported that overall image is one of the most important

factors to elicit the intention to revisit the same destination

(Alcaniz, Garcia, & Blas, 2005; Bigné et al., 2001).

Word-of-mouth (WOM) is defined as “informal, person-toperson communication between a perceived noncommercial

communicator and a receiver regarding a brand, a product, an

organization, or a service” (Harrison-Walker, 2001, p. 63). Due to

the intangible nature of a service product, a consumer’s purchase

decision usually involves higher levels of perceived risk than

purchasing manufactured products. Positive WOM is an excellent

source to reduce perceived risk for its clarification and feedback

opportunities (Murray, 1991). In addition, it is considered an

important information source influencing consumer’s choice of

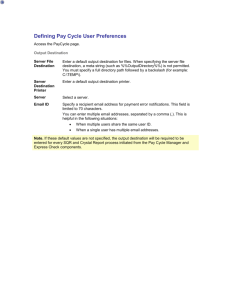

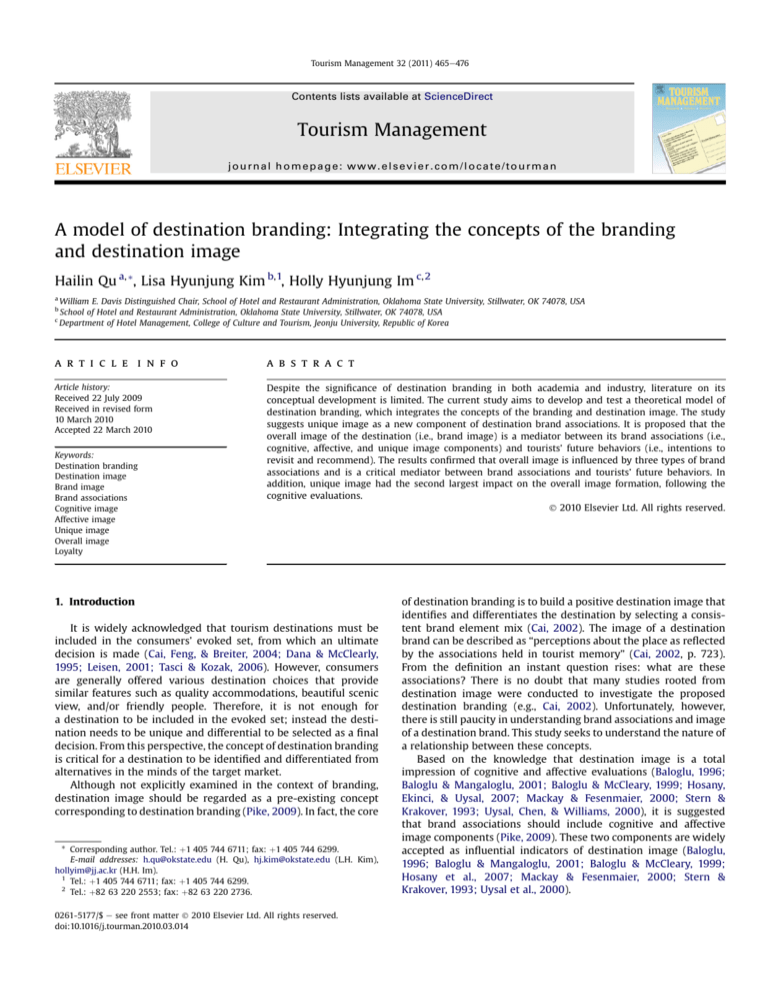

Fig. 1 represents the conceptual framework of building destination branding.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling

The target population of this study was domestic visitors, who

stopped at five selected welcome centers in Oklahoma during an

eight-week period in July and August 2002. A confidence interval

approach was used to determine the sample size, suggested by

Burns and Bush (1995). With 50% of the estimated variability in the

population (Burns & Bush, 1995), the sample size was set at 379

(n ¼ 379) at the 95% confidence level. Assuming a response rate of

25% and unusable rate of 5%, a total of 1264 (379/0.30) people were

approached to participate in the survey.

Two stages of sampling approach were used in this study:

proportionate stratified sampling and systematic random sampling

(SRS). The top five largest welcome centers (Thackerville, Sallisaw,

Colbert, Erick, and Miami) were selected in terms of number of total

attendance in July and August 2001 (OTRD, 2002). The subsample

size of each welcome center was then stratified proportionately.

Cognitive

image

H1

Unique

image

H2

H3

Intention to

revisit

H4

Overall

image

H5

Affective

image

Fig. 1. A model of destination branding with hypothesized paths.

Intention to

recommend

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

The next step was to select the interval of the samples (nth) by

using a SRS. The interval of the sample (nth) was determined by

dividing the previous total visitor number of the five welcome

centers by the number of attendance at each of the five welcome

centers. Every nth visitor who stopped at the five welcome centers

was approached to participate in the survey. A random starting

number for each day was created. A set of questionnaires along

with an instruction letter was distributed to the five welcome

centers according to a proportionate subsample size for each

welcome center.

3.2. Instrument

The survey questionnaire consisted of four major sections. The

first section included questions relating to the individual travel

behavior of respondents and the information source used prior to

planning a trip to Oklahoma. The travel behavior items included the

number of times they visited Oklahoma, purpose for the trip, length

of stay, and total trip spending.

The second section was developed to assess the respondent’s

cognitive, affective, and perceptions of overall image toward

Oklahoma as a travel destination. To generate a complete list of the

respondent’s perceptions associated with cognitive images,

a method used by Echtner and Ritchie (1993) was adapted. During

the review of the literature on destination image measurement, all

the attributes used in the previous studies were recorded and

grouped by the researcher into a “master list” of attributes. In

addition, two focus group sessions were held with twelve participants each developing multi-item scales capturing various aspects

of Oklahoma’s image as a travel destination. For additional input,

various travel literature and promotional brochures on Oklahoma’s

tourism were also reviewed. The last step was to have a panel of

expert judges, who are academics and practitioners in the areas of

tourism, marketing, and consumer behavior, examine the complete

list of attributes to eliminate redundancies and to add any missing

attributes. Finally, 28 items relating to cognitive image were

selected and respondents were asked to rate Oklahoma as a travel

destination on each of 28 attributes on a 5-point Likert scale where

1 ¼ Strongly Disagree (SD); 2 ¼ Disagree (D); 3 ¼ Neutral (N);

4 ¼ Agree (A); and 5 ¼ Strongly Agree (SA).

Affective image of destination was measured by using affective

image scales developed by Russel et al. (1981). The scale included

four bipolar scales: Arousing-Sleepy, Pleasant-Unpleasant, ExcitingGloomy, and Relaxing-Distressing. A 7-point semantic-differential

scale was used for all four bipolar scales where the positive poles

were assigned to smaller values: 1 ¼ arousing and 7 ¼ sleepy,

1 ¼ pleasant and 7 ¼ unpleasant, 1 ¼ exciting and 7 ¼ gloomy, and

1 ¼ relaxing and 7 ¼ distressing. In addition, the scale of overall

image measurement was modified from Stern and Krakover (1993).

The respondents were asked to rate their perception of overall

image of Oklahoma on a 7-point scale with 1 being very negative

and with 7 being very positive.

The third section was to identify the attributes that make

Oklahoma unique from neighboring states (Arkansas, Kansas,

Missouri, and Texas) as a travel destination. A total of 15 items were

derived from the image study of Plog Research (1999a, 1999b) and

various travel literature and promotional brochures on Oklahoma

as well as neighboring states with a 5-point Likert-type scale

(1 ¼ strongly disagree; 5 ¼ strongly agree). Although some of the

similar measures were used for capturing cognitive and unique

images of Oklahoma, they should be considered as different

measures because cognitive image measures the perceptions of the

general quality of tourist experiences in Oklahoma as a travel

destination (without any comparison with other destinations)

while unique image has more focus on comparison of measures

469

between Oklahoma and neighboring states. It is possible that one

image item perceived strong in cognitive image could be less strong

when compared with neighboring states/competitors. For example,

attributes such as beaches, oceans, and tropical climate are the

general characteristics that represent Jamaica as a tourist destination, yet they are not perceived unique when the focus becomes

uniqueness of the destination (Echtner & Ritchie, 1993).

Additional two questions were included to determine the

respondent’s intention to revisit Oklahoma and the respondent’s

intention to recommend Oklahoma as a favorable destination to

others with a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 ¼ most unlikely; 5 ¼ most

likely). The final section was devoted to collecting demographic

information about the respondents.

A pilot test was performed to assess how well the survey

instrument captured the constructs it was supposed to measure,

and to test the internal consistency and reliability of questionnaire

items. The first draft of the survey instrument was distributed to 20

randomly selected visitors who stopped at Thackerville Welcome

Center, the largest welcome center among the 12 Oklahoma

welcome centers in terms of number of visitors. A total of 20

questionnaires were collected at the site.

The results of the reliability tests for each dimension showed

that Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 for cognitive items and 0.75 for

uniqueness of Oklahoma, indicating above the minimum value of

0.70, which is considered acceptable as a good indication of reliability (Hair et al., 1998). Based on the results of the pilot test and

feedback from OTRD, the final version was modified considering

questionnaire design, wording, and measurement scale.

3.3. Data analysis

Principal component analyses were used to determine the

underlying dimensions of the cognitive and unique image

components of Oklahoma. Confirmatory factor analysis and SEM

were utilized to test the conceptual model of destination branding.

The data was processed with the statistical package SPSS 16.0 and

LISREL 8.8.

4. Results

4.1. Underlying dimensions of cognitive image

The result of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant

(c2 ¼ 3431.49, p ¼ 0.00), indicating that nonzero correlation existed. The overall value of MSA was 0.930, which was well above the

recommended threshold of sampling adequacy at the minimum of

0.50 (Hair et al., 1998). These two tests suggested that the data was

suitable for an exploratory factor analysis. A principal component

analysis with orthogonal (VARIMAX) rotations was assessed to

identify underlying dimensions of cognitive image.

Based on the eigenvalue greater than one, scree-plot criteria,

and the percentage of variance criterion, five factors were chosen

which captured 58.5% of the total variance. Among the 28 image

attributes, four items had communalities less than .50 and factor

loading less than .40. These variables are “lots of adventurous

activities,” “reasonable cost of shopping centers,” “a wide choice of

accommodations,” and “availability of facilities for golfing/tennis.”

When there are variables that do not load on any factor or whose

communalities are deemed too low, each can be evaluated for

possible deletion (Hair et al., 1998). The dropping of these variables

with low communalities and low factor loadings increases the total

variance explained approximately 4% (from 58.5% to 62.1%). The

results of the principle component analysis with orthogonal

(VARIMAX) rotations are shown in Table 1. The scree plot indicated

that four factors may be appropriate; however, based on

470

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

Table 1

Dimensions of cognitive destination image.

Attributes

Factor loadings

Factor 1: Quality of experiences

Easy access to the area

Restful and relaxing atmosphere

Reasonable cost of hotels/restaurants

Scenery/natural wonders

Lots of open space

Friendly local people

F1

Communality

.798

.723

.662

.651

.589

.574

Factor 2: Touristic attractions

Local cuisine

State/theme parks

Good place for children/family

Welcome centers

Good weather

Cultural events/festivals

Good shopping facilities

.719

.645

.641

.570

.641

.591

F2

.667

.663

.648

.645

.627

.617

.501

Factor 3: Environment and infrastructure

Clean/unspoiled environment

Infrastructure

Availability of travel information

Easy access to the area

Safe and secure environment

.657

.645

.663

.605

.562

.597

.606

F3

.744

.705

.698

.697

.573

Factor 4: Entertainment/outdoor activities

Entertainment

Nightlife

Water sports

A wide variety of outdoor activities

.671

.602

.702

.630

.601

F4

.727

.678

.658

.640

.688

.610

.653

.639

Factor 5: Cultural traditions

Native American culture

A taste of cowboy life and culture

Eigenvalue

Variance (%)

Cumulative variance (%)

Cronbach’s alpha

F5

.591

.461

8.8

19.4

19.4

0.86

5.3

13.1

32.5

0.76

a combination of scree plot and eigenvalue greater than one

approach, five factors were retained.

The scale reliability for each factor was tested for internal

consistency by assessing the item-to-total correlation for each

separate item and Cronbach’s alpha for the consistency of the entire

scale. Rules of thumb suggest that the item-to-total correlations

exceed .50 and lower limit for Cronbach’s alpha is .70 (Hair et al.,

1998). The results of the item-to-total correlation indicated that

each of the five factors exceeded the threshold of .50 ranging

between .63 and .74. The results showed that the alpha coefficients

for the five factors ranged from .71 to .86.

Factors were labeled based on highly loaded items and the

common characteristics of items they included. The factors’ labels

are “Quality of Experiences” (Factor 1), “Touristic Attractions”

(Factor 2), “Environment and Infrastructure” (Factor 3), “Entertainment/Outdoor Activities” (Factor 4), and “Cultural Traditions”

(Factor 5). These five factors were later used to construct summated

scales as independent variables for structural equation modeling

(SEM) for hypotheses testing.

4.2. Underlying dimensions of unique image of Oklahoma

The results of a measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated that unique image set was

appropriate for factor analysis. Based on the eigenvalue greater

than one, scree-plot criteria, and the percentage of variance criterion, three factors were extracted through principal component

analysis with oblique (PROMAX) rotations. The three-factor model

captured 46.1% of the total. A total of three items had communalities less than .50 and factor loading less than .40. These variables

2.1

12.9

45.5

0.75

1.4

9.8

55.3

0.72

.626

.578

1.2

6.8

62.1

0.71

are “value for money,” “a wide variety of state/theme parks,” and

“moderate prices for hotel/restaurant/shopping.” The dropping of

these variables with low communalities and low factor loadings

increases the total variance explained approximately 6% (from

46.1% to 52.3%). Table 2 shows the results of the principle component analysis with oblique (PROMAX) rotations. The scree plot

indicated that three factors may be appropriate. A combination of

Table 2

Dimensions of unique destination image.

Attributes

Factor loadings

Factor 1: Native American/Natural

environment

Native American/Western cultures

Friendly and helpful local people

Scenery and natural wonders

Restful and relaxing atmosphere

Clean environment

F1

0.81

0.72

0.70

0.68

0.67

Factor 2: Appealing destination

Appealing as a travel destination

Entertainment/nightlife

A wide choice of outdoor activities

Shopping

Safe and secure environment

0.76

0.70

0.67

0.56

0.53

F2

0.75

0.71

0.69

0.62

0.60

Factor 3: Local attractions

Lots of tourist attractions

Cultural/historical attractions

Eigenvalue

Variance (%)

Cumulative variance (%)

Cronbach’s alpha

Communality

0.70

0.72

0.62

0.60

0.56

F3

0.83

0.65

3.9

32.5

32.5

0.85

1.2

10.3

42.8

0.74

1.1

9.5

52.3

0.71

0.74

0.69

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

Table 3

Three-construct measurement model.

Variables/indicators

Table 5

CFA results e modified model construct loadings (t values in parentheses).

Indicator loadings on constructs

Perceptual/

cognitive image

x1

x2

x3

x4

x5

x6

x7

x8

x9

x10

x11

x12

Quality of experiences

Touristic attractions

Environment and infrastructure

Entertainment/outdoor activities

Cultural traditions

Native American/natural

environment

Appealing destination

Local attractions

Pleasant

Arousing

Relaxing

Exciting

471

Unique

image

Variables

Affective

image

Quality of experiences

Touristic attractions

Environment and infrastructure

Entertainment/outdoor activities

Native American/natural

environment

Appealing destination

Local attractions

Pleasant

Relaxing

Exciting

x1

x2

x3

x4

x5

L1

L2

L3

L4

L5

x6

x7

x8

x9

x10

L6

L7

L8

L9

L10

L11

L12

Loadings

Reliability

Variance

extracted

0.86

0.85

0.74

0.75

0.80

(11.54)

(12.86)

(10.29)

(10.55)

(11.53)

0.88

0.69

0.76

0.59

0.69

0.65

0.64

0.71

0.50

(6.82)

(6.27)

(6.23)

(7.12)

(4.78)

0.65

0.50

standardized coefficients exceeding or very close to 1.0; (3) very

large standard errors associated with any estimated coefficients

(Reisinger & Turner, 1998). In the case of negative error variances

(Heywood case), no offending error variances were found in the

estimates for the measurement model. If correlations in the standardized solution exceed 1.0 or two estimates are highly correlated,

one of the constructs should be removed (Hair et al., 1998). Based

on this, two indicators for exogenous variables, which were greater

than 1.0 was deleted. The deleted variables were “cultural traditions” (cognitive image) and “arousing” (affective image). The

modified measurement model was then re-estimated for assessing

overall model fit. The overall model fit statistics for the CFA were

good (c2, 61.02 df ¼ 49, p < .05, GFI ¼ .97, AGFI ¼ .94, TLI ¼ .90),

indicating that the individual indicators are behaving as expected.

With the overall model being accepted, each of the constructs

can be evaluated separately by (1) examining the indicator loadings

for statistical significance and (2) assessing the construct’s reliability and variance extracted. First, for each variable, the t values

associated with each of the loadings exceed the critical values at the

0.05 significance level (Hair et al., 1998). These results indicated

that all variables were significantly related to their specified

constructs, verifying the posited relationships among indictors and

constructs.

Next, estimates of the reliability and variance extracted

measures for each construct were assessed to determine whether

the specified indicators were sufficient in their representation of

the constructs. The results of loadings with t values and computations for each measurement are shown in Table 5. In terms of

reliability, two exogenous constructs, cognitive image (0.88) and

unique image (0.76), exceed the suggested level of 0.70. Affective

image (0.65), however, is close to the threshold of 0.70; thus

marginal acceptance can be given on this measure. The results of

estimates of the reliability measure for three constructs with all

significant t values support the convergent validity of the items in

scree plot and eigenvalue greater than 1 approach selected three

factors.

Factors were labeled based on highly loaded items and the

common characteristics of items they included. They are labeled

as “Native American/Natural Environment” (Factor 1), “Appealing

Destination” (Factor 2), and “Local Attractions” (Factor 3) (Table 2).

The item-to-total correlation of each factor met the cutoff of .50,

indicating the range between .62 and .75. The alpha coefficients

for the three factors through the Cronbach’s alpha test range from

.71 to .85.

4.3. Measurement model

Through principal component analyses, the five underlying

dimensions of cognitive image and the three dimensions of unique

image were identified. In addition, one of the constructs in the

hypothesized model, affective image, has four measures including

pleasing (X9), arousing (X10), relaxing (X11), and exciting (X12).

Combined, all these twelve constructs were operationalized in the

measurement model (Table 3). There is no reason to expect

uncorrelated perceptions; thus the factors are allowed to correlate

as well (Hair et al., 1998).

For purposes of CFA in this study, a covariance matrix was

employed (Table 4). LISREL program (version 8.8) was chosen to

estimate the measurement model and the construct covariances.

4.4. Offending estimates

Before evaluating the measurement model, offending estimates

were examined. The common examples are: (1) negative error

variances or nonsignificant error variances for any construct; (2)

Table 4

Covariance matrix for CFA.

x1

x2

x3

x4

x5

x6

x7

x8

x9

x10

x11

x12

Variables

x1

x2

x3

x4

x5

x6

x7

x8

x9

x10

x11

x12

Quality of experiences

Touristic attractions

Environment and infrastructure

Entertainment/outdoor activities

Cultural traditions

Native American/natural environment

Appealing destination

Local attractions

Pleasant

Arousing

Relaxing

Exciting

15.13

13.44

6.38

3.94

2.87

2.99

1.57

1.27

0.46

0.01

1.60

0.36

19.18

7.61

5.9

3.27

3.34

1.93

1.71

0.33

0.21

1.28

0.56

9.83

4.75

1.98

2.5

1.94

1.12

0.28

0.07

0.77

0.02

6.04

1.31

1.69

1.50

0.97

0.06

0.04

0.43

0.21

1.63

1.12

0.67

0.41

0.15

0.03

0.53

0.06

3.90

1.49

0.98

0.15

0.10

0.53

0.06

2.64

1.06

0.18

0.17

0.56

0.13

1.40

0.13

0.12

0.31

0.13

0.90

0.03

0.21

0.02

0.84

0.02

0.05

2.01

0.30

1.25

472

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

Table 6

SEM results: standardized parameter estimates for SEM model construct loadings (t value in parentheses) e structural model.

Endogenous

constructs

Overall image

Revisit

Recommend

Cognitive factors

Unique factors

Affective factors

Structural

equation fit (R2)

Overall Image

Revisit

Recommend

0.000

0.41 (3.61)**

0.25 (2.02)*

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.62 (4.58)**

0.000

0.000

0.35 (2.49)*

0.000

0.000

0.21 (1.96)*

0.000

0.000

0.53

0.43

0.21

Note: *Significant at 0.05 level (critical value ¼ 1.96).

**Significant at 0.01 level (critical value ¼ 2.576).

each scale. In terms of variance extracted, all three constructs,

cognitive image (0.69), unique image (0.59), and affective image

(0.50), exceed or just meet the threshold value of 0.50.

4.5. Structural model

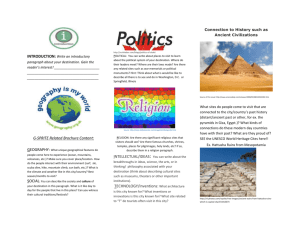

Based on the results of CFA, the structural model was tested. The

overall model fit statistics show that the model is acceptable to

represent the hypothesized constructs (c2, 57.49 df ¼ 49, p < .05,

CFI ¼ .98, GFI ¼ .97, AGFI ¼ .95, RMSEA ¼ .03, RMSR ¼ .074). All the

paths proposed in the structural model were statistically significant

and of the expected positive direction (Table 6). Thus, all five

hypotheses failed to be rejected.

Hypothesis 1, the more positive cognitive image of a destination,

the more likely visitors would have the positive overall image of the

destination, was failed to reject (standardized coefficient ¼ 0.62; t

value ¼ 4.58; Sig. 0.01). Hypothesis 2 also failed to be rejected

(standardized coefficient ¼ 0.21; t value ¼ 1.96; Sig. 0.05), supporting that the visitor’s perception of overall image is positively

influenced by affective image. Hypothesis 3 tested the positive

relationship between unique image and overall image. It also failed

to be rejected (standardized coefficient ¼ 0.35; t value ¼ 2.49;

Sig. 0.05), suggesting that the unique image of a destination has

a positive influence on overall image. The results confirmed that

cognitive image has the strongest effect on overall image, followed

by unique and affective images, respectively. Hypotheses 4 and 5

tested the mediating role of overall image on the relationships

between the three destination brand images and tourist behaviors

(i.e., intention to revisit and intention to recommend). The results

supported the mediating role of overall image.

As a final approach to model assessment, we compared the

proposed model with a competing model. A nested model

approach was adopted as the competing models strategy. The first

model (MODEL 1) positions overall image in a fully mediating role

between three types of brand associations (i.e., cognitive, unique,

and affective images) and the intentions to revisit and recommend

(see Fig. 2). The second model (MODEL 2) allows for both direct and

indirect effects (mediated through overall image) of the brand

associations on intentions to revisit and recommend. The results of

a c2 difference test suggested that there is no significant difference

1

2

Estimated Full

Mediatio

Model

(Model 1)

2

1

3

3

1

2

Competing

Partial

Mediation

Model

(Model 2)

2

1

3

3

1=

1 = Cognitive Image; 2 = Unique Image; 3 = Affective Image

Overall Image; 2 = Intention to revisit; 3 = Intention to recommend

Fig. 2. Path diagrams of estimated full model (MODEL 1) and competing partial model (MODEL 2).

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

0.27

X1

0.29

X2

0.47

0.49

0.86

0.85

0.74

0.36

X5

0.51

X6

0.59

X7

X8

0.62

0.62 (4.58)**

0.75

X9

0.70

X10

0.57

0.66

H2

0.69

Unique

Image

Intention to

revisit

H4

0.80

0.35 (2.49)*

Overall

Image

0.41 (3.61)**

H5

0.65

0.25 (2.02)*

0.64

Intention to

recommend

0.21 (1.96)*

0.71

0.50

Y2

H1

H3

0.64

0.57

Y1

Cognitive

Image

X3

X4

473

Affective

Image

0.45

0.50

Y3

0.75

Note: * Significant at p < .05 (critical value=1.96); ** Significant at p < .01 (critical value=2.576).

2

= 57.49; df = 49; p value = 0.38; NFI = 0.71; GFI = 0.98; AGFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.030.

Variance explained (R2) in Overall image ( 1) = 0.53; Intention to revisit ( 2) = 0.43;

Intention to recommend ( 3) = 0.21.

Fig. 3. Results of destination branding model.

between MODEL 1 and MODEL 2 (Dc2 ¼ 3.45, Ddf ¼ 6). Therefore,

the parsimonious model (MODEL 1) is retained.

Fig. 3 shows the model of destination branding.

5. Conclusions and implications

This study aimed to test a theoretical model of destination

branding. It was proposed that destination image (i.e., brand image)

is a multi-dimensional construct, influenced by the cognitive,

unique, and affective images that collectively affect tourist behaviors. Overall, the results showed that destination image exerts

a mediating role between the three image components as the brand

associations and the behavioral intentions. Strong and distinctive

destination image should not only be a goal of branding practices in

capturing consumers’ minds but also as a mediator to influence

consumer behaviors, directly related to the success of the tourist

destinations. Therefore, in the competitive tourism market, tourist

destinations must establish a positive and strong brand image,

derived from the cognitive, unique, and affective image associations, to increase repeat visitors and to attract new tourists to the

destination.

The results confirm the previous argument that the image of

a destination directly influences intentions to revisit and recommend the destination to others (Alcaniz et al., 2005; Bigné et al.,

2001). Although not explained in the results, this study found

that overall image was perceived more positively by repeat visitors

than by first time visitors (at p .01). It supports the relationship of

overall image on revisits. Furthermore, in tourism, where its

consumption is relatively infrequent, the positive influence of

overall image on recommendations should be emphasized more so

than before. For potential tourists, recommendation is an important

information source in forming an image toward the particular

destination (Bigné et al., 2001). Thus, tourism destinations need to

provide favorable experiences to tourists, in which they will create

a positive image and recommend the place to others in turn helping

potential tourists develop a favorable image that affects the destination choice.

It is interesting to note that through comparing the competing

model to the proposed full mediating model, the more conservative

mediating model is supported. It means that rather than being

impacted by the distinct image components, tourist behaviors are

influenced by the total impressions of the destination, which is the

combination of the cognitive, unique, and affective image components. It supports the argument by Baloglu and Brinberg (1997) that

image components are closely intertwined and may not be isolated

unless the subjects are inquired in that way. In other words, it is the

overall image, as a total impression based on the three image

components, which influences tourists’ future behaviors.

As expected, cognitive image positively influences overall

image. This result confirms the results of other studies (Baloglu &

McCleary, 1999; Stern & Krakover, 1993), arguing for the positive

effect of cognitive image on overall image. The results show that

a cognitive image (i.e., the belief s and knowledge of attributes of

the destination) is the most influential brand association to form

overall image.

The significance of unique image on overall image warrants

a need for more attention on this construct from destination

branding scholars. Interestingly, its effect was even larger than the

affective image component, which has received more consideration

than unique image in the destination image literature. The results

also show that uniqueness of a destination has the second largest

influence on overall image. The importance of unique image also

lies in its usefulness to positioning the destination brand. Because

unique image is an excellent source for differentiation (Echtner &

474

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

Ritchie, 1993), it needs to be identified and emphasized to improve

overall image and increase the points of difference among various

alternatives. Thus, little attention has focused on the construct in

the literature, unique image should be considered as a critical brand

association to expand our knowledge of destination image to the

next level of destination branding.

This work supports the results of Baloglu and McCleary’s (1999)

study that affective image is significantly influential on overall

image. However, contrary to Baloglu and McCleary’s findings,

which found the stronger impact of affective evaluation on overall

image than that of cognitive evaluation, this study found that

cognitive image is more influential on the overall image. The

difference between the two results may be due to (1) the different

treatment on the cognitive construct, (2) investigation of the

different stages of destination image formation, and/or (3) inclusion of unique image in this study. First, Baloglu and McCleary

(1999) used three separate variables to understand the cognitive

evaluation of a destination while the current study adopted one

variable to measure the cognitive image construct. This procedure

might produce different results. In addition, while Baloglu and

McCleary’s study examined the image prior to the actual visitation

to the destination, this study explored the complex image to

understand the phenomenon. That is, affective image may have

more impact on overall image before actual visitation whereas

cognitive image may exert more influence on overall image when

actual visitation is realized. Furthermore, the inclusion of unique

image should influence the weaker impact of affective image on

overall image. It is argued that affective image can be diverse

among different destinations and used for positioning strategy

(Baloglu & Brinberg, 1997). It is possible that the differentiating

contribution of affective image on overall image is explained partly

by unique image, leading to much weaker contribution of affective

image on overall image than those of cognitive and unique image

components. Future research should examine the relationship

among the three image components for a more clear understanding

on destination branding.

As Cai (2002) claimed, destination image cannot expand to

destination branding without the consideration of brand identity.

This study argued that brand identity needs to be created and/or

enhanced based on a clear understanding of the destination image

that consumers have formed. Based on the results, the current

study claims that cognitive, unique, and affective evaluations on

destination must be identified to understand the brand image of

a destination for its significant effects on overall image. Moreover,

the perceived image (i.e., brand image or overall image of a destination) should be assessed with the projected image (i.e., brand

identity) by the destination. The assessment offers information to

build the desired image that is consistent with the brand identity of

the destination (Cai, 2002). If the perceived image is not consistent

with brand identity, the source(s) of the problem must be identified

and corrected (Kotler & Gertner, 2004). Promoting brand identity

without fixing the current problems would cause negative wordof-mouth communications due to the discrepancy between the

expectations and the actual performance. Positioning strategy must

be implemented to create the desired brand image in the minds of

the target market. In addition, tourism destinations should monitor

the destination image regularly to examine if the projected image is

well adopted by tourists. This is because consistency of core identity is critical for the success of long-term oriented destination

branding practices.

In addition to the theoretical contribution on destination

branding, this study provides practical implications especially

salient for the state of Oklahoma. Based on the results of the study,

a positioning strategy of the State of Oklahoma as a destination

brand is proposed (Table 7). It reflects all the key components of

a destination brand including its positioning, its rational (head) and

emotional (heart) benefits and associations, together with its brand

personality (Morgan & Pritchard, 2004).

Positioning strategy should start with identifying the strong

elements that uniquely differentiate a destination from competitors

(Crompton et al., 1992). The current study identified several differentiating attributes of the State of Oklahoma such as “Native American/western heritage,” “restful atmosphere,” “clean environment,”

and “natural beauty.” As Aaker and Shansby (1982) suggested, only

one or at the most two attributes should be used for brand positioning. Emphasizing too many attributes simultaneously may

deteriorate the maximum level of implementation of core identity.

Consequently, “Land of Native American and western heritage” is

recommended as a positioning proposition for the state of Oklahoma.

The positioning of Oklahoma as a land of Native American and

western heritage is translated into the rational benefit of encountering unspoiled wilderness, western heritage, and natural and

dramatic beauty. Further, these benefits offer visitors the emotional

benefits of feeling uplifted by the spirituality of the natural environment, relaxed by the unspoiled and clean countryside, and fulfilled by experiencing the western heritage and history of Oklahoma.

Finally, the culmination of these brand attributes is a destination

personified by relaxed, down to earth, pleasant, and traditional yet

open-minded traits. This should become the essence of Oklahoma. In

summary, the findings of the overall study provide a clear brand

position for Oklahoma’s destination brand. Brand Oklahoma

emerged as a clear, focused strategy with a defined purpose and

personality. Oklahoma’s pristine environment and Native American

heritage make it well suited to marketing a clean, nature-based

tourism destination with friendly, spirited people and the freedom

and space to travel. Once the brand identity with strong and

distinctive attributes and brand personality are proposed, it is critical

to provide an integrated and consistent marketing communications

to the target market. It is possible through partnerships and cooperations between the government and the industry.

5.1. Limitations and recommendations for future study

One limitation of this study is that the data collection was

conducted in the summer. A traveler’s characteristics and images of

the state of Oklahoma as a travel destination may vary by season

(e.g., summer, winter, etc.). For example, a traveler who has visited

Oklahoma in the summer season may vary from a different image

and perception toward Oklahoma as a travel destination as opposed

to that who has traveled in the winter. Thus, the findings of this

Table 7

A positioning strategy of the state of Oklahoma as a destination brand.

Positioning

Rational benefit

Emotional benefit

Personality

Land of Native American

and western heritage

I feel uplifted by the spirituality of the natural environment.

I feel relaxed by the unspoiled and clean countryside.

I feel fulfilled by experiencing the western heritage

and history of Oklahoma.

I feel soothed by the open, unspoiled outdoors.

Unspoiled wilderness

Tradition

Western heritage

Natural and dramatic beauty

Friendly local people

Note: Adopted from the brand architecture of Britain (source: Morgan & Pritchard, 2002, pp. 34e35).

Relaxed

Down to earth

Pleasant

Hearty and friendly

Traditional yet open-minded

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

study are limited to images of Oklahoma for summer pleasure

travelers. To overcome this limitation, a survey can be conducted in

different seasons. Then, the results of the survey should be

analyzed if there are any differences in image and perceptions of

Oklahoma between travelers in different seasons.

Second, the population of this study was limited to visitors who

stopped at the selected five welcome centers out of twelve in

Oklahoma. Although these five welcome centers were selected

based on the total number of visitors, the results may be only

applicable for the travelers from these welcome centers. It may not

be generalizable for those who did not stop by any of the welcome

centers during their trip to Oklahoma. In addition, the total

response rate was low (24.5%), suggesting that this study was

limited to generalizing the large portion of visitors who did not

participate in the survey.

Third, there may be other factors influencing the development

of destination image. This study was limited to the included variables, which are consistently and repeatedly mentioned and

partially supported by empirical results in the literature. Therefore,

the results of this study may have excluded additional destination

brand associations that might have helped better explain tourist

destination choice behavior. For example, socio-psychological

travel motivations of an individual were suggested by numerous

tourism scholars as a crucial construct to form tourism destination

images. Future research should investigate additional destination

brand associations that may influence overall image and tourist

behaviors.

Fourth, the number of questions measuring certain constructs in

the model is constrained by the practical need to develop a parsimonious questionnaire. The findings are limited to the selected

items measuring the related constructs. We suggest that future

research utilize more items to measure designated constructs.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. New York: The Free Press.

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong brands. New York: The Free Press.

Aaker, D. A., & Shansby, J. G. (1982). Positioning your product. Business Horizons, 25

(3), 56e62.

Alcaniz, E. B., Garcia, I. S., & Blas, S. S. (2005). Relationships among residents’ image,

evaluation of the stay and post-purchase behavior. Journal of Vacation

Marketing, 11(4), 291e302.

Ashworth, G., & Goodall, B. (1988). Tourist image: marketing considerations. In

B. Goodall, & G. Ashworth (Eds.), Marketing in the tourism industry: The

promotion of destination regions (pp. 213e238). London: Routledge.

Baker, B. (2007). Destination branding for small cities: The essentials for successful

place branding. Portland: Creative Leap Books.

Baloglu, S. (1996). An empirical investigation of determinants of tourist destination

image. Unpublished dissertation. Virginia Polytechnic University, Blacksburg,

Virginia.

Baloglu, S., & Brinberg, D. (1997). Affective images of tourism destination. Journal of

Travel Research, 35(4), 11e15.

Baloglu, S., & Mangaloglu, M. (2001). Tourism destination images of Turkey, Egypt,

Greece, and Italy as perceived by US-based tour operators and travel agents.

Tourism Management, 22(1), 1e9.

Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of

Tourism Research, 26(4), 868e897.

Bigné, J. E., Sánchez, M. I., & Sánchez, J. (2001). Tourism image, evaluation variables

and after purchase behavior: inter-relationship. Tourism Management, 22(6),

607e616.

Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2005). Destination branding: insights and

practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel

Research, 43(4), 328e338.

Botha, C., Crompton, J. L., & Kim, S. (1999). Developing a revised competitive

position for Sun/Lost City, South Africa. Journal of Travel Research, 37(4),

341e352.

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism

Management, 21(1), 97e116.

Burns, A. C., & Bush, R. F. (1995). Marketing research. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Cai, A. (2002). Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Annals of Tourism

Research, 29(3), 720e742.

Cai, L. A., Feng, R., & Breiter, D. (2004). Tourist purchase decision involvement and

information preferences. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(2), 138e148.

475

Calantone, R. J., Benedetto, A. D., Hakam, A., & Bojanic, D. C. (1989). Multiple

multinational tourism positioning using correspondence analysis. Journal of

Travel Research, 28(2), 25e32.

Chon, K. S., Weaver, P. A., & Kim, C. Y. (1991). Marketing your community: image

analysis in Norfolk. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 31(4),

31e37.

Cooper, C., Fletcher, J., Gilbert, D., & Wanhill, S. (1993). Tourism: Principles and

practice. London: Pitman Publishing.

Crompton, J. L., Fakeye, P. C., & Lue, C. (1992). Positioning: The example of the lower

Rio Grande Valley in the winter long stay destination market. Journal of Travel

Research, 31(2), 20e26.

Dana, C. J., & McClearly, K. W. (1995). Influencing associations’ site-selection

process. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 36(2), 61e68.

Echtner, C. M., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1993). The measurement of destination image: an

empirical assessment. Journal of Travel Research, 31(4), 3e13.

Fan, Y. (2006). Branding the nation: what is being branded? Journal of Vacation

Marketing, 12(1), 5e14.

Florek, M. (2005). The country brand as a new challenge for Poland. Place Branding,

1(2), 205e214.

Florek, M., Insch, A., & Gnoth, J. (2006). City council websites as a means of place

brand identity communication. Place Branding, 2(4), 276e296.

Gartner, W. C. (1993). Image formation process. Journal of Travel and Tourism

Marketing, 2(2/3), 191e215.

Go, F., & Govers, R. (2000). Integrated quality management for tourist destinations:

a European perspective on achieving competitiveness. Tourism Management, 21

(1), 79e88.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data

analysis (5th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication

and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential

antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60e75.

Hosany, S., Ekinci, Y., & Uysal, M. (2007). Destination image and destination

personality. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1

(1), 62e81.

Kapferer, J. (1997). Strategic brand management. Great Britain: Kogan Page.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based

brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1e22.

Keller, K. L. (1998). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing

brand equity. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Keller, K. L. (2008). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring, and managing

brand equity (3rd ed.). New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Konecnik, M., & Go, F. (2008). Tourism destination brand identity: the case of

Slovenia. Brand Management, 15(3), 177e189.

Kotler, P., & Gertner, D. (2004). Country as brand, product and beyond: A place

marketing and brand management perspective. In N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, &

R. Pride (Eds.), Destination branding: Creating the unique destination proposition

(2nd ed.). (pp. 40e56) Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kozak, M., & Rimmington, M. (2000). Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an

off-season holiday destination. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 260e269.

Kurt, K. (1999 December 27). Oklahomans are still trying to shake dust from state’s

image. The Sunday Oklahoma A1.

Leisen, B. (2001). Image segmentation: the case of a tourism destination. Journal of

Services Marketing, 15(1), 49e66.

Low, G. S., & Lamb, C. W. (2000). The measurement and dimensionality of brand

associations. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 9(6), 350e368.

Mackay, K. J., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2000). An exploration of cross-cultural destination image assessment. Journal of Travel Research, 38(4), 417e423.

Mansfeld, Y. (1992). From motivation to actual travel. Annals of Tourism Research, 19

(3), 399e419.

Mihalic, T. (2000). Environmental management of a tourist destination: a factor of

tourism competitiveness. Tourism Management, 21(1), 65e78.

Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2002). Contextualizing destination branding. In

N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination branding (pp. 10e41).

Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2004). Meeting the destination branding challenge. In

N. Morgan, A. Pritchard, & R. Pride (Eds.), Destination branding: Creating the

unique destination proposition (2nd ed.). (pp. 59e78) Burlington, MA: Elsevier

Butterworth-Heinemann.

Morrison, A., & Anderson, D. (2002). Destination branding. Available from: http://

www.macvb.org/intranet/presentation/DestinationBrandingLOzarks6-10-02.

ppt Accessed 18.05.03.

Murray, K. B. (1991). A test of services marketing theory: consumer information

acquisition Activities. Journal of Marketing, 55(1), 10e25.

Mykletun, R. J., Crotts, J. C., & Mykletun, A. (2001). Positioning an island destination

in the peripheral area of the Baltics: a flexible approach to market segmentation. Tourism Management, 22(5), 493e500.

Nandan, S. (2005). An exploration of the brand identity-brand image linkage:

a communications perspective. Brand Management, 12(4), 264e278.

Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department (OTRD). (2002). Available from:

http://tourism.state.ok.us/travel_and_tourism.htm. Accessed 05.07.04.

Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department (OTRD). (2003). Available from:

http://tourism.state.ok.us/travel_and_tourism.htm Accessed 05.07.04.

Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department (OTRD) (2006 November 8). Oklahoma tourism segmentation.

476

H. Qu et al. / Tourism Management 32 (2011) 465e476

Oppermann, M. (2000). Tourism destination loyalty. Journal of Travel Research, 39

(1), 78e84.

Pike, S. (2009). Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home

destinations. Tourism Management, 30(6), 857e866.

Plog Research, Incorporation (1999a). The 1999 American traveler survey: Oklahoma

as a destination.

Plog Research, Incorporation (1999b). Travelers’ awareness and perception of Oklahoma as a leisure destination.

Reisinger, Y., & Turner, L. (1998). Asian and western cultural differences: the new

challenge for tourism marketplaces. Journal of International Hospitality, Leisure

& Tourism Management, 1(3), 21e35.

Ritchie, J. R. B., Ritchie, R. J. B. (1998). The branding to tourism destination: past

achievements & future challenges. In: Marrakech, Morocco: Annual congress of

the International Association of Scientific Experts in Tourism.

Rosenberg, L. J., & Czepiel, J. A. (1984). A marketing approach to customer retention.

Journal of Consumer Marketing, 1(2), 45e51.

Russel, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 39(6), 1161e1178.

Russel, J. A., & Pratt, G. (1980). A description of affective quality attributed to

environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 311e322.

Russel, J. A., & Snodgrass, J. (1987). Emotion and environment. In D. Stockols, &

I. Altman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (pp. 245e280). New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

Russel, J. A., Ward, L. M., & Pratt, G. (1981). Affective quality attributed to environments: a factor analytic study. Environment and Behavior, 13(3), 259e288.

Ryan, C., & Gu, H. (2008). Destination branding and marketing: the role of

marketing organizations. In H. Oh (Ed.), Handbook of hospitality marketing

management (pp. 383e411). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Stern, E., & Krakover, S. (1993). The formation of composite urban image.

Geographical Analysis, 25(2), 130e146.

Sussman, S., & Ünel, A. (1999). Destination image and its modification after travel:

An empirical study on Turkey. In A. Pizam, & Y. Mansfeld (Eds.), Consumer

behaviour in travel and tourism (pp. 207e226). New York: The Haworth

Hospitality Press.

Tasci, A. D. A., & Kozak, M. (2006). Destination brands vs destination images: do we