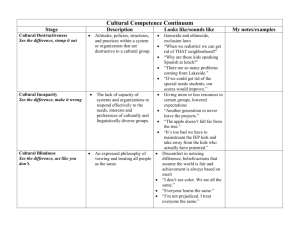

Organizational Cultural Competence: A Review of

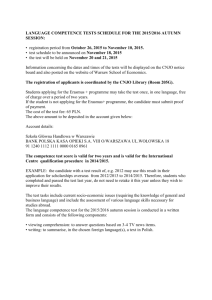

advertisement