“MOO” in Latin?

advertisement

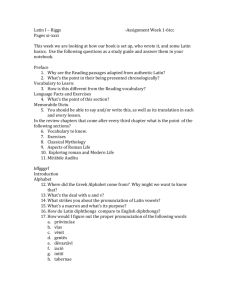

John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton How Do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Assessing Student Learning and Motivation in Beginning Latin John Gruber-Miller Cindy Benton Cornell College ABSTRACT In this article, we assess the value of VRoma for Latin language learning. In particular, we discuss three exercises that we developed which combine Latin language and Roman culture in order to help students reinforce their Latin skills and gain a more in-depth understanding of ancient Roman society. Daily journals and evaluations of the assignments provided an assessment of student motivation and gave us information concerning students’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of working in the VRoma MOO. Transcripts and e-mail responses, both composed in Latin, allowed us to assess both the quality of students’ interaction in the target language and their understanding of cultural and linguistic structures. Our studies have shown that by combining visual arts and cultural data with the capacity for real time communication in Latin, VRoma provides a unique opportunity for students to be immersed in language and culture simultaneously. Such an opportunity is not only useful for developing students’ language skills but also for giving them a more sophisticated understanding of the ways that language and culture are integrated. KEYWORDS Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL), Computer Mediated Communication (CMC), Intercultural Awareness, Interaction, Latin Language Instruction, Latin MOOs, Task-Based Language Learning, Network-Based Language Learning (NBLL), Student Motivation, VRoma © 2001 CALICO Journal Volume 18 Number 2 305 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? INTRODUCTION The development of network-based language learning environments (see Warschauer, 2000) and educational MOOs (see Lee, Groves, Stephens, & Armitage, 1999) in particular has opened new possibilities for foreign language teachers. The VRoma project (www.vroma.org) is one such educational MOO, a re-creation of second century Rome that combines a series of chat rooms with web pages to create a virtual city where students and teachers can explore ancient Rome and interact with one another. (For an overview of the VRoma project, see McManus, this issue.) Our involvement with VRoma inspired us to create three exercises to see if VRoma is as useful for Latin language learning as it is for studying culture in Roman civilization courses. The first assignment was a treasure hunt designed to familiarize students with the layout of second century Rome while practicing their Latin composition and reading skills. The second assignment was a version of “Clue” called Indicium. Students tried to find out who killed a character called Argus by interacting with each other in order to find clues and solve the mystery. The third assignment was Quaere, a version of the card game “Go Fish.” Students were put in groups and assigned to a specific region of VRoma. As students tried to collect a set of four different objects, they had to communicate in Latin with other members of their group in order to find and trade objects. The three activities of our project (Treasure Hunt, Indicium, and Quaere) were designed with several goals in mind: to help students to integrate culture and language, to reinforce certain grammatical constructions and lexical items, and to create effective activities that would motivate students to find Latin interesting. We also wanted to test several hypotheses about how students learn best in this MOO environment. Did the MOO environment enhance student learning of the Latin language and Roman culture? Did students learn best individually, competitively, or collaboratively? Did they learn grammar and vocabulary better when they were using the language to actively create meaning of their own rather than creating textbook exercises? Could a computer-mediated environment enhance students’ ability to integrate language and culture? Did the MOO affect students in a positive way so that they wanted to learn more about ancient Rome? The project involved two second semester Latin classes in 1999 and one in 2000 at Cornell College. The students in the two sections in 1999 participated in the Treasure Hunt and Indicium exercises while those in the section in 2000 completed an additional third activity, Quaere. The games were played twice during each course. Utilizing student evaluations, journals, and transcripts, we collected data from 19 students in 1999 and 14 students in 2000. 306 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton The place of MOOs in Learning Language and Culture The three activities of our project brought together a number of strands in contemporary research in second language acquisition and pedagogy. Studies on the importance of culture, interaction, computer-mediated communication, and student learning styles informed the variety of tasks we asked our students to perform in the MOO. Each of the exercises that we created worked to integrate language and culture as students interacted with each other in virtual Rome. Cross-Cultural Awareness Culture—after listening, speaking, reading and writing—has been called the fifth skill. The Standards (1996) of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) lists culture as the second of the five standards necessary for learning a language. As Steele (1990) has eloquently written, “Every word, every expression we use has a cultural dimension … . Speakers of a language share not only the vocabulary and structure of a language; they share the perceptions of reality represented by that vocabulary and structure.” As experienced language teachers know, vocabulary items and grammatical structures rarely have a simple one-toone correspondence from one language to another. For language learners to succeed in communicating, they need to understand the values, attitudes, customs, and rituals of a culture that are expressed in what they hear and read, speak, and write. Language reading specialists, in particular, stress the importance of both language decoding skills (bottom-up skills) and the background cultural and rhetorical information (top-down strategies) to understand written texts. In other words, teaching grammar and vocabulary is not enough in helping students become fluent in the target language. They need an understanding of the target culture, too. Granted the importance of studying culture, one of the great concerns of foreign language educators is how to integrate culture into the curriculum. Yet, the challenge for language learners is not only to learn about culture but to understand it from the inside out. Latin textbooks often offer culture capsules or readings about specific aspects of ancient Rome. Some reading textbooks even incorporate culture into the story line of the book, depicting the main character going to school, seeing the army come through town, participating in a community religious festival, or traveling to Rome. If we were to describe what topics someone should know about culture, we might use the outline provided by Pfister and Borzilleri (1977) 1) the family unit and the personal sphere (e.g., family relationships, eating, shopping, and housing), Volume 18 Number 2 307 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? 2) the social sphere (e.g., class structure, work, leisure, attitudes toward sex, and population), 3) political systems and institutions (e.g., government, education, law, and justice), 4) the environment (e.g., geography, economy, urban vs. rural, natural resources, the environment, and weather), and 5) Religion, the arts, and the humanities (e.g., role of religion, mythology, folklore, history, literature, music, and creative arts). Many Latin reading textbooks cover many of these topics, and, as a result, when students begin to read, they are able to grasp basic cultural assumptions that inform what they read in authentic texts. Yet, these topics are primarily descriptive; they do not show how one topic affects another or how they are interrelated. In other words, the study of culture needs to go beyond simply learning information about the culture. Language learners need to understand the process of how a culture works, for example, how politics impinges on religion, how attitudes about class and status effect individual perceptions, how Romans experienced entertainment. They then need to compare these processes and practices with their own culture (Standard 4.2). Recent work on teaching culture shows that students (and teachers) tend to compartmentalize language study as distinct from the study of culture, to exaggerate differences between cultures, and to generalize from these differences to all people of a culture (see the studies summarized by Robinson-Stuart & Nocon, 1996). In addition, Hall and Ramirez (1993) suggest that language learners who are not actively guided to seek similarities between themselves and speakers of the target language come to objectify both target language speakers and English speakers as different and distinct from themselves. Although several models exist for incorporating second culture acquisition into the classroom (e.g., Crawford-Lange & Lange, 1984; Kramsch, 1993, Robinson-Stuart & Nocon, 1996; Seelye, 1984), Hanvey’s (1979) model for inter-cultural understanding provides a good way of measuring student perception of culture. According to Hanvey, understanding between cultures will only occur when language learners begin to go beyond superficial recognition of similarities and differences and begin to see these differences as intellectually understandable, as motivated within a cultural framework, and, finally, understandable because they approach the differences from within the target culture. According to Hanvey, there are four stages for measuring cross-cultural awareness (see Table 1). 308 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Table 1 Four Stages for Measuring Cross-Cultural Awareness Level Information Mode Interpretation Level 1 Awareness of superficial or very visible cultural traits; stereotypes Tourism, textbooks Unbelievable (i.e., exotic, bizarre) Level 2 Awareness of significant and subtle cultural traits that contrast markedly with one’s own Culture conflict situations Unbelievable (i.e., frustrating, irrational) Level 3 Awareness of significant and subtle cultural traits that contrast markedly with one’s own Intellectual analysis Believable cognitively Level 4 Awareness of how another culture feels from the standpoint of the insider Cultural immersion Believable because of subjective familiarity The virtual world of VRoma offers Latin students and teachers a place for maximizing cultural understanding. The VRoma program provides a reconstruction of the city of Rome in the mid-second century CE that gives students a spatial realization of the city of Rome, that organizes Roman history, values, and culture in a spatial and physical context. Moreover, the program does not segment culture into distinct spheres but shows, instead, how culture impinges on the social order and how the political realm affects the religious world of the Romans. When students visit the Roman Senate Building in the Forum, for example, they see images and descriptions of Roman clothing and the Latin vocabulary used to describe it. They understand this vocabulary within a cultural, visual, and spatial context that gives it more cultural specificity than simply a garment of clothing called a toga. It is garment that marks status, class, and gender and helps reinforce the Roman political and social hierarchy. If students try to “put on” the toga, they are greeted by a senatorial scribe who takes it back, contemptuously remarking that it is worn only by curule magistrates. As a result, students feel the effect of their own class on their ability to participate in (virtual) Roman culture. In a similar way, visitors to Rome not only read descriptions of monuments but also come into contact with a flying crow (corvus) that used to greet the emperor each day. Such a blending of fact and anecdote, culture and history has its roots in Volume 18 Number 2 309 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Roman imperial travel writers such as Strabo and Pausanias who traveled throughout the empire to explore the customs, cultures, and monuments of the various parts of the Roman world. Such a model of situated learning, we hypothesized, would provide students the opportunity to begin to understand Roman culture from the inside out. Interaction and Tasks in Network-Based Language Learning We were also led to use VRoma MOO with our students because of how network-based language learning helps promote language learning through interaction and task-based activities. Studies over the last two decades have pointed out the benefits of interaction between two speakers or between reader and text for promoting language learning. As Ellis (1984) has said, Interaction contributes to development because it is the means by which the learner is able to crack the code. This takes place when the learner can infer what is said even though the message contains linguistic items that are not yet part of his competence and when the learner can use the discourse to help him/her modify or supplement the linguistic knowledge used in production. In other words, when students interact with each other or another more native speaker, they are forced to process the incoming data and come up with a response. At times, the communication will break down, and it is at these moments of communication breakdown that students will have to negotiate new meaning and modify their exchange so that communication can continue. (For an overview of this process, see Pica, 1994.) For this negotiation to take place, it is up to the student to pay conscious attention to what part of the exchange was not understood and then modify it. In modifying their output, “learners test hypotheses about the second language, experiment with new structures and forms, and exploit their interlanguage resources in creative ways” (Pica, Lewis, & Morgenthaler, 1989). Output also has the effect of increasing accuracy and consolidating learners’ control over forms that have already been internalized (Nobuyoshi & Ellis, 1993). Finally, output provides the opportunity for students “to move from the semantic processing prevalent in comprehension to the syntactic processing needed for production” (Swain & Lapkin, 1995). In short, interaction and negotiation leads to restructuring of students’ grammar and syntax and ultimately to acquisition. One of the ways that researchers and teachers have developed for bringing about interaction consists of language tasks that require an exchange of information. Pica, Kanagy, and Faldoduna (1993) argue that three types 310 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton of tasks, jigsaw (in which each participant holds part of the information necessary for task completion), information gap (in which one person holds information that another requires for task completion), and problem-solving are especially suitable for creating opportunities for interaction by everyone since in each type only one task outcome is possible. Yet, each differs somewhat with respect to the comprehension, feedback, and production required for successful task completion. The jigsaw, because each participant holds information needed by the rest of the group, provides the greatest interaction for all members of the group. The information gap task is slightly less interactive because the information flows one-way, not two-way, as in the jigsaw. Finally, the problem-solving task is the least restrictive in how the task might be successfully completed and allows for the most variability in interaction to solve the task. Research on Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) and NetworkBased Language Learning (NBLL) has revealed that these interactions appear to enhance language learning environemnts. Research on CMC has shown that more students participate in on-line conversation than in face-to-face discussion, that the interaction is more balanced among students, and that students contribute more in the on-line environment than in a classroom setting. Researchers have also found that on-line discussion is lexically and syntactically more complex than face-to-face discussion. (For overviews of the research, see Beauvois, 1997; Warschauer, 1997.) The advantages of CMC and NBLL for interaction and language learning arise for at least two reasons: learner control and time to think and reflect. Since students control the discourse rather than the instructor, they interact more and feel safer to express themselves. In addition, since students have more time to think and reflect, even in synchronous communication such as a MOO, they have time to notice grammar and syntax and to produce more complex sentences than they might in a faceto-face conversation. As Beauvois (1992) aptly puts it, CMC is “conversation in slow motion.” It combines the rapid interchange associated with conversation with the time for reflection connected with writing in a single medium. As Warschauer (2000) demonstrates in his introduction to Network-Based Language Teaching, NBLL encourages learners to use the computer as a tool for interaction with others, for collaborative learning, and for the construction of knowledge. The dynamic of working with the computer one-on-one, he points out, is shifting to interacting with others via the computer. Student Learning Styles and Motivation Another concern of foreign language teachers is how to reach students with different cognitive and learning styles. The integration of text and Volume 18 Number 2 311 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? image in the VRoma MOO appeals to greater numbers of students than text only. In addition, the combination of descriptive texts and brief essays with ancient narratives and anecdotes provides students with a greater number of different kinds of resources for understanding Latin and Roman culture. Relatively brief introductions on topics were developed with additional links to more information that help students delve deeper without being overwhelmed by too much information all at once. (On the design of the Circus and its subterranean bookstore/library, see McManus, this issue.) The VRoma MOO versus other Language MOOs Over the last half dozen years, a plethora of MOOs focusing on language learning has emerged: LeMOO français, MundoHispano, SchMOOze (English), Morgen Grauen, Little Italy, Mugit (the University of Pennsylvania’s Latin MOO), MOOsaico (Portuguese) (see Sanchez, 1996; Turbee, 1996; Shield, Weininger, & Davies, 1999). While MOOs offer many benefits to language learners, Latin students face obstacles not encountered by students of modern languages. Unlike modern languages, Latin students cannot interact with native speakers in CMC environments. However, although they cannot take advantage of this aspect of CMC, the Web provides an opportunity for immersion in ancient Roman culture in ways that even a visit to Rome itself cannot offer. By reconstructing a virtual city of Rome just as it was in the second century CE, students are able to get a feel for what life was like in the ancient city. They can encounter other Latin speakers (live and robots), explore the city’s art and architecture, and learn about Roman cultural institutions. Latin provides the common language for interaction between people from all over the globe enabling students to interact with a broader community outside their classrooms (and their institutions). Turbee (1996) argues that chatting with native speakers, forming relationships, and building personal spaces is a motivating factor for students to return to the MOO to learn and use the target language. While the first factor is not possible for Latin students, forming relationships with other students outside the classroom and building personal spaces could also be motivating forces for VRoma users. While other users may not be native speakers, the possibility of encountering other Latin speakers and the chance to practice Latin could also motivate VRoma users as well. The program provides students with a re-creation of the city itself which integrates the visual resources of a web page and the interactive abilities of a chatroom. It also provides links to Latin texts and more detailed cultural information. 312 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton VROMA EXERCISES As we designed exercises using the resources of VRoma, we had several goals in mind. First, we wanted to create a variety of exercises that would accommodate various learning styles and would take advantage of the situated learning environment VRoma offers. Specifically, we wanted students to interact with each other in Latin while being immersed as much as possible in Roman culture. We hoped that this environment would feel like a more natural place to practice Latin and that the exposure to the material, social, and political culture of Rome would enable students to understand the experience of being in the city and comprehend the ways that public and private spaces were organized and lived in thousands of years ago. The sequence of assignments was designed to build upon the technological skills and cultural knowledge acquired in the prior exercises. The first few VRoma assignments encouraged students to expand their knowledge of Roman culture, while the final exercise required them to use the knowledge they had gained in previous exercises to complete the task successfully. In addition, as the assignments progressed, each exercise required more interaction, improvisation, and cooperation among students as well as more familiarity with MOO commands. A Trip to the Baths We started with an orientation session in English and designed our first assignment to serve as an introduction to VRoma and basic MOO skills. Timed to coincide with chapter 23 of the Oxford Latin Course (OLC) (1996), the assignment focused on Trajan’s baths. This location in VRoma offers a series of rooms designed to recreate the experience of being in the ancient Roman baths. Visitors move from the entryway into the appropriate apodyterium ‘changing room’ where they are greeted by either an ancilla ‘slave girl’ or servus ‘male slave’ robot who offers assistance for a small fee. As visitors wander from the apodyterium through the caldarium ‘hot room,’ frigidarium ‘cold room,’ tepidarium ‘warm room,’ and palaestra ‘wrestling ground,’ they find descriptions of each room accompanied by an appropriate picture illustrating the unique characteristics of that space. A variety of objects are scattered throughout the rooms such as the sandals in the apodyterium which help to acquaint visitors with bath culture. After reading “Marcus Quintum ad balnea ducit” ‘Marcus leads Quintus to the baths’ in the OLC, students are given instructions explaining how to log on to the VRoma MOO and where to find Trajan’s baths. Then they are asked to explore the complex by taking Quintus’ route through the various rooms and describe what they see. While they are exploring the Volume 18 Number 2 313 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? site, they are also asked to find a series of objects and to explain their functions. Afterward, they are asked to compare Trajan’s baths to those visited by Quintus. Our goals in designing this assignment included teaching students basic MOO navigational skills and making them familiar with the variety of resources available in VRoma. We chose this particular site because it offers images, objects, and links, and provides students with an opportunity to practice activating and interacting with a robot in English. In addition, it allowed us to expand upon the information about bath culture provided in the OLC by giving students the opportunity to experience a virtual recreation of an actual Roman bath. Treasure Hunt Once students were comfortable logging on and navigating through a VRoma web page in English, we gave them an exercise that would build upon these skills and incorporate Latin. The Treasure Hunt is an asynchronous exercise designed to help students practice reading, writing, and communication skills in Latin. It requires them to read and understand both adapted and unadapted original Latin, to interact with a Latin-speaking robot, and to respond in Latin to several questions. All of these activities take place in a situated learning environment that allows students to integrate the experience of language and culture. For example, the directions for part III of the Treasure Hunt follow. (See directions for all Treasure Hunts in Appendix A.) i Romam. deinde, procede ad regionem VIII (preme numerum VIII in mappa XIV regionum). deinde, i ad rostra. 1. quae clara avis prope rostra habitabat? quid avis faciebat? quis avem occidit? cur? 2. procede ad monumentum avis. ubi est monumentum? quid in monumento inscriptum est? 3. estne fabula vera an falsa? 4. mitte magistro/magistrae electronica responsa. ‘Go to Rome, then proceed to region 8 (press the number 8 in the map of the 14th region). Then, go to the rostra. 1. Which famous bird used to live near the rostra? What did the bird do? Who killed the bird? Why? 2. Proceed to the bird’s monument. Where is the monument? What was inscribed on the monument? 3. Is this story true or false? 4. Send an electronic response to your instructor.’ 314 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton First of all, students need to be able to read and understand the directions. However, any difficulty recalling vocabulary can be alleviated by the visual prompts encountered in the site. If they have forgotten avis ‘bird,’ for instance, the picture of Corvus (the crow) should jog their memories. In order to answer question number one above, students must find and read the Pliny text that accompanies the description of Corvus. Both the Latin text and its English translation are provided. The availability of both languages provides students with the vocabulary necessary to answer the question in Latin, while giving them a translation to assist them with difficulties they might have understanding the Latin. By activating Corvus, students also have an opportunity to practice communicating in Latin on another level. The corny puns uttered by Corvus also enrich the assignment with humor. Best of all, students are able to use and develop their Latin skills in a meaningful context that encourages them to find out more information about the environment in which they find themselves and communicate that information to others. The need to describe their experience serves as a motivating force for acquiring new vocabulary and grammatical structures. As students navigate through the various parts of the city and visit buildings such as the Via Appia, the theater of Marcellus, and the curia ‘Senate Building,’ they begin to learn about Roman political systems, class structure, the use of urban space, religion, and the arts. For example, Part II—also set in the rostra ‘speaker’s platform’—integrates language learning with further understanding of architecture and history as well as the impact of politics on speech and the use of public space. In this exercise, students learn about the function and history of the rostra. They are also asked to find a set of scrolls containing Cicero’s orations against Anthony and read about Cicero’s death. As students stand at the rostra and read both the speeches of Cicero and the accounts of his death, they can begin to imagine the chilling impact that the sight of Cicero’s severed head and hands nailed to the rostra would have had on the speeches given in that space (Richlin, 1999). Such an exercise both increases their awareness of Roman history and enriches their understanding of Quintus’ encounter with Cicero in the OLC. Because this exercise is asynchronous, it allows students who need a little more time to become comfortable in the MOO to work at a more leisurely pace. They can continue to improve their computer skills while completing the assignment without the pressure of keeping up with students who are more confident or experienced with the technology. Completing the assignment successfully, however, does require them to continue to develop the necessary skills that enable them to participate confidently in the synchronous exercises. Alternatively, students who are more comfortable in the MOO environment can complete the assignment and investigate the resources available to them without waiting for others who Volume 18 Number 2 315 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? may still be struggling with the technology. Asynchronous assignments like this one also allow students to continue to improve their technological and language skills, as well as their knowledge of Roman culture, outside of class time. We found that the treasure hunts were indeed popular extra credit assignments, and students often asked for additional treasure hunts to complete on their own. Thus, the exercise was also successful in engaging students and generating interest in language, culture and technology. As students continued to explore the various parts of Rome, interact with various characters and areas of the city, and report their findings in the target language, they were able to expand their knowledge of Roman culture, geography, and the Latin language in an integrated environment. Although the treasure hunt is an asynchronous exercise, it does fit into the information gap category of interactive tasks enumerated by Pica et al. (1993). In this case, it is the VRoma MOO itself that holds all the information necessary to answer the questions. Yet because the holder of the information is often static text, the interaction is not always conversational and is limited to interactions between reader and text. Nonetheless, interactivity is possible through encounters with Latin-speaking robots and e-mail exchanges between student and teacher. True conversation and real time interaction is provided by the exercises that follow in the sequence. Indicium Both Indicium and Quaere require more immersion in Roman culture and VRoma. In these exercises, students are not simply tourists or visitors to Rome, but inhabitants. Students are assigned a persona (matrona ‘married woman,’ botularius ‘sausage seller,’ conviva ‘dinner guest,’ uxor ianitoris ‘janitor’s wife,’ and miles ‘soldier’) and asked to develop a description, in Latin, of their character. They must then interact with each other in character. By adopting ancient Roman personae and engaging in group role play, students are encouraged to take their understanding of Roman society to another level, one that not only encourages identification with a person from a foreign culture but possibly a person of another gender or class depending on the luck of the draw. As a synchronous exercise, Indicium provides students with an opportunity to converse with one another in Latin within appropriate regions of the MOO. Adapted from Hasbro’s Clue game, students are grouped and assigned to specific places in VRoma such as the Domus Paulli et Corneliae, Balneae, Forum, or Campus Martius. Each person is then assigned a character along with several clues (e.g., instrumenta mortis ‘murder weapon,’ dramatis personae ‘character,’ and loca facti ‘crime scene’). Students must then solve the mystery of Argus’ death by taking turns guessing who killed 316 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton him, where it was accomplished, and with which implement. The assignment is designed to get students used to the technicalities of synchronous communication in the MOO at the same time that they practice the targeted syntactical and lexical material: passive voice, plural imperatives, the accusative and ablative cases, and, later, purpose clauses and deponent verbs. Students quickly learn that they need to be in the same room to converse with each other and thus have a need to use the targeted grammar and vocabulary, for example, me sequimini ad apodyterium ‘Follow me to the changing room.’ Once students make an accusation (e.g., “credo: Argus a caupone in apodyterio occisus est fune” ‘I believe Argus was killed by the innkeeper in the changing room with the rope.’ or “credo: caupo ad apodyterium festinavit ut Argum fune occideret” ‘I believe the innkeeper hurried to the changing room in order to kill Argus with the rope.’ (depending on the targeted construction), they indicate whether or not they have one of the clues (e.g., “funem habeo” ‘I have the rope.’ or “indicium non habeo” ‘I don’t have a clue.’), which allows the process of deduction to begin. When students believe they have the mystery solved, the person makes an accuso ‘accusation.’ In order to win the game, students must not only identify the killer, place, and implement of death but must make a grammatically correct accusation. While the Treasure Hunt exercises accommodate independent learners, Indicium is tailored to students who work better in a more interactive environment. To facilitate smoother interaction, students are asked to prepare their characters as part of a homework assignment and are given worksheets to complete the exercise before going into the laboratory. The worksheets contain the rules of the game, sample sentences, and the necessary vocabulary with blank spaces to decline the nouns ahead of time. The worksheets are completed in class, and some time is devoted to practicing the syntax orally, with written reinforcement on the board before heading to the lab. (See sample directions for Indicium in Appendix B.) The Indicium game emphasizes the jigsaw mode of information exchange discussed by Pica et al. (1993). Each participant holds a number of clues needed by the rest of the group, yet all must contribute in order to solve the mystery of the murder. The game thus requires the participation of all students since each student has information the rest of the group needs. The game is also the most structured of the assignments. It necessitates taking turns, following specific rules, and adhering to syntactical formulas as they interrogate and respond to each other. The formulaic nature of the exercise can provide some comfort to students who are less comfortable with either the grammar or the technology by structuring their interactions with others as they try synchronous communication and navigation for the first time. Additionally, because students respond and interrogate in a strict order, they have time between turns to formulate their questions and responses more slowly and accurately. Volume 18 Number 2 317 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Quaere The Quaere is also a synchronous exercise; however, instead of competing against each other as in Indicium, students must work together to complete the task successfully. Students are assigned to a specific complex in VRoma such as the Theater of Marcellus, Trajan’s Baths, or the House of Paullus and Cornelia. They then work together as a team to deduce which people and which objects belong in which rooms of the complex. Again, for this assignment, students are assigned characters and asked to write brief descriptions of themselves. Before the game starts, they are given dossiers that indicate who their character is and where they will begin the game as well as a list of objects and rooms in which to play the game. The objects themselves are scattered randomly throughout the complex. When students log on and meet in the designated room, they must introduce themselves to each other and then determine (by conversing in Latin) which room is appropriate for their character, which objects are appropriate for the room, and which are appropriate for the common room. For example, the group assigned to Trajan’s Baths should determine that the ancilla ‘slave girl’ would collect the vestimenta ‘clothing’ and place them in the apodyterium ‘changing room.’ (See directions for Quaere in Appendix C.) The rules of the game are constructed so that students must converse with each other and trade objects instead of merely collecting the objects individually. Students successfully complete the task when all the characters are in their respective rooms with their appropriate objects. This task is not only more collaborative but is also the most spontaneous and least restrictive of the assignments. The interaction not only requires communication, but negotiation. Students move freely throughout the complex asking teammates if they are carrying or have seen the desired objects. In addition, it requires students to develop further MOO skills such as picking up, dropping, and exchanging objects. The more natural, less scripted dialogue encourages students to think on their feet in Latin and gives them the opportunity to develop more syntactical and lexical variety. Additionally, students must demonstrate their knowledge of material culture and the use of public and private space. Understanding the politics of space also gives them an appreciation for the ways in which class affected social and political life. For instance, in order to successfully complete the Quaere assignment that takes place in the Theater of Marcellus, students must be able to demonstrate their knowledge of the way in which social hierarchy is embedded in the configuration of architectural space. They need not only to recognize the divisions between spectator and performer but also to demonstrate how spectators themselves were seated by class (Rawson, 1987; Zanker, 1988). 318 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Because Quaere requires students to develop MOO skills such as picking up, dropping, and exchanging objects, they become competent in all the skills required to converse and interact with others in the MOO. More important, they have had the experience of communicating in Latin with other inhabitants of Rome as they further their understanding of the material and social culture of the ancient city in the target language. ANALYSIS OF THE DATA Students were asked to keep a daily journal and complete an evaluation at the end of the course to assess their experience using the VRoma MOO. (See the end of course evaluation in Appendix D.) They were also asked to assess their confidence using technology before and after the course. Transcripts of MOO sessions and of student e-mail exchanges with the instructor provided us with another form of feedback concerning the project. It must be pointed out that the journal and evaluations record students’ self-perception of their knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward the various aspects of the project. Analysis of students’ evaluations, journals, and transcripts confirmed many of our goals for the project. First, we asked students to assess their level of technical skill using e-mail, a web browser, and MOOs or MUDs. The vast majority of students asserted that they had a lot of experience (85%: 4 or 5 on a five-point scale) or a fair amount of experience (6%: 23 on the five-point scale) using e-mail and a web browser to perform tasks such as opening the browser and navigating the World Wide Web (4 or 5 on a scale of 0-5). Only a few (9%) reported that they had little experience (0 or 1 on the five-point scale) with e-mail and the Web before the course began. Even though most of the class considered themselves experienced computer users, few had had experience with a MUD or MOO. Most students (61%) reported that they had had little or no experience with MOOs and MUDs, a sizeable minority (24%) had some experience, while only 15% reported that they had a lot of experience (see Table 2). Table 2 Students’ Responses to Questions on Experience Using Technology Before After Experience Little Moderate Very Little Moderate Very Computer 3 2 28 0 2 31 MOO 20 8 5 0 7 26 Volume 18 Number 2 319 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? By the end of the course, the vast majority of the students reported confidence using e-mail, the Web, and the MOO. The vast majority (94%) asserted that they were very comfortable using e-mail and the Web (4 or 5 on the five-point scale). Only two students (6%) stated that they were not fully confident in using e-mail and the Web, yet even they reported a moderate degree of confidence using the technology (2 or 3 on a 0-5 scale). Students’ MOO skills developed even more rapidly. Once again, 79% of the students expressed great confidence in their ability to function in the VRoma MOO environment, while the other 21% were moderately confident in using the MOO. In other words, students quickly learned the skills necessary for functioning well in an environment rich in technology and did not find in general that the technology impeded their completion of the three different types of activities in the VRoma MOO. Indeed, most students found using the VRoma MOO satisfying. Combining responses from questions 1-6 in the Content section of the evaluation, 76% of the students found the activities utilizing the VRoma MOO very useful or moderately useful. What they found most useful, overwhelmingly, was the cultural component of the MOO. In rating which aspect of language learning VRoma activities help most, culture received the highest rating, 3.51, a full point above the next highest categories, vocabulary and composition (see Table 3). Table 3 Means of Students’ Improvement in Language Learning by Category Culture Vocabulary Composition Reading Grammar Interaction 1999 4.37 2.84 2.58 2.53 2.21 N. A. 2000 2.36 2.05 2.17 2.06 1.86 2.33 Mean 3.51 2.51 2.40 2.27 2.06 2.33 This result is confirmed by the open-ended comment section at the end of the evaluation. In response to the question “what was the biggest benefit of using the MOO?” students reported 19 times that the cultural and historical information embedded in the text and images of the MOO enhanced their understanding of ancient Rome (see Table 4). 320 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Table 4 Number of Student Comments on the Benefits of the VRoma MOO Comment Number Culture/History 19 Break from classroom/book 8 Visual/virtual world 7 Fun 6 Grammar/composition 6 Interaction/collaboration 5 Anonymity 1 Learning new technology 1 In addition, the activity that students favored most was the Treasure Hunt, the activity that in their eyes most explicitly presented information about culture (see Table 5). Table 5 Means of Students’ Views of Specific MOO Activities Culture Vocabulary Composition Reading Grammar Interaction Treasure Hunt 3.07 2.36 2.50 2.83 2.07 1.86 2.45 Quaere 2.07 1.86 2.14 1.79 1.79 2.57 2.04 Indicium 1.93 1.93 1.86 1.57 1.71 2.57 1.93 Total Note: The means are based on 2000 data. At the same time, the evaluations and journals pointed to other benefits of the VRoma MOO. Students recognized that the activities in the MOO helped them with language learning. When students were asked which specific aspects of VRoma helped them learn best, they asserted that conversing (mentioned 105 times), textual descriptions (91 times), and viewing objects (88 times) were the most beneficial, pointing to the value of interaction, whether student-to-student, student-to-robot, or student-andtext (see Table 6). Volume 18 Number 2 321 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Table 6 Number of Times Students Mentioned Categories in Evaluations Culture Vocabulary Composition Reading Grammar interaction* Total Conversing 11 15 24 21 18 16 105 Textual description 34 16 8 17 13 3 91 Viewing objects 27 20 8 17 13 3 88 Robots 20 6 10 12 4 4 56 Images 31 7 3 5 5 3 54 Virtual world 19 7 4 7 4 5 46 Creating characters 9 2 8 1 1 2 23 Note: The number of comments in the Interaction column is based on 2000 data. Even though much of the textual description in the MOO was in English, students recognized the value of the MOO for developing vocabulary (2.51), composition (2.40), and reading (2.27) (see Table 3 above). In response to the open-ended question “What was the biggest benefit of using the MOO?” six students mentioned the value of the MOO for learning grammar and syntax, and five commented on its importance for interaction with others in the target language (see Table 4 above). Interestingly, student comments in journals stressed the importance of the MOO for learning grammar (14 comments) followed by fun (seven comments), culture and history (five comments), and interaction and collaboration (four comments) (see Table 7). 322 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Table 7 Number of Student Comments on the Value of the MOO Comment Number Grammar/composition 14 Fun 7 Cultural/history 5 Interaction/collaboration 4 Break from classroom 3 Visual/virtual world 1 Note: The number of comments is based on 2000 data Students recognized a third benefit of using the MOO. Even though we had not allowed space for questions of motivation and learning styles in the rest of the evaluation, many students stressed in their write-in comments that the MOO provided a different and motivating resource for learning language and culture. Eight students commented that the MOO provided a break from classroom routine or from the textbook, seven noted that the visual and spatial aspects helped them understand Roman life with a new perspective, and six simply stated that it was fun (see Table 4 above). In short, students found the MOO to be a place to learn culture and language in a space that is motivating and adapted to different learning styles. Challenges/Further Refinements Although a large majority of the students found the VRoma exercises helpful for learning Latin and Roman culture, they faced some challenges. Despite feeling comfortable using the MOO, navigation posed a problem for several reasons (see Table 8). Volume 18 Number 2 323 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Table 8 Number of Student Comments on Challenges Using the MOO Comment Number Technology/navigation 18 Collaboration 4 Slow connection 3 Grammar 2 Relevance 2 Computer availability 1 Understanding 1 First, some students tried moving from room to room with the @go command and were transported to unofficial sections of the MOO where students from other schools had created rooms with similar names. During the Treasure Hunt exercise, students were occasionally unable to find all the requested items because they did not explore the site deeply enough to take advantage of all the available on-line resources. On other occasions, communication broke down and students failed to say where they were going so that others could interact with them. Students also mentioned that collaboration was a problem four times. At times, during Quaere for example, students failed to greet each other as they entered rooms or say farewell as they exited. This situation left students who wanted to exchange objects frustrated. At other times, during Indicium, some students were confused about when to take a turn which left the other members of the group waiting for either a suggestion or a confirmation that they had a clue. Finally, a few students were too competitive and tried to circumvent the rules so that they could win the game. When students were asked to comment on how to improve the MOO experience, the most prevalent comment was the need for clearer instructions and documentation for the activities (see Table 9). 324 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Table 9 Number of Student Comments on Ways to Improve the MOO Comment Number Clearer documentation/instructions 9 Longer/more sessions 6 Optional/homework/outside class 4 Use only for culture 4 Comprehensive maps 3 Restrict interactions to Latin 3 More feedback 2 Better AI of robots 1 Get rid of it 1 Latin penpals from other schools 1 Less formula exercise 1 More Latin composition and reading preparation 1 In addition, they also thought that sessions should be longer and more frequent so that they could become more familiar with the rules and nuances of the games. They also suggested restricting the interactions to Latin. Although the use of Latin was our intent, a review of the transcripts indicated that sometimes students reverted to English. In many cases, switching to English was understandable because students’ language levels varied, and, once one student started using English, the others joined in. This problem could have been exacerbated by the bilingual nature of typing in VRoma. Because VRoma is designed to appeal to a larger audience, much of the textual description and all of the MOO commands are in English. Additionally, students were not able to use case endings as they were picking up and dropping objects because all the objects needed to be labeled in the nominative. All three of these difficulties could be solved by more careful sequencing of classroom and VRoma activities. Devitt (1997) and Skehan (1996) recommend balancing form-focused instruction with task-based activities. Students need the opportunity to analyze form and rehearse lexical items before they are ready to engage in interactive activities such as Indicium Volume 18 Number 2 325 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? and Quaere. For example, although we had students complete a practice sheet that involved declining nouns, it might have also been useful to ask students to anticipate their encounters with others in the MOO and to generate sample questions and dialogue ahead of time. In addition, some class time devoted to developing characters and rehearsing roles in pairs would have facilitated smoother interaction in the MOO. Moreover, follow-up exercises such as revising transcripts would have helped them to consolidate their knowledge of Latin vocabulary and syntax. CONCLUSIONS The VRoma MOO is indeed useful for learning language. Students found that the process of immersion in a cultural context emulating the experience of being in ancient Rome facilitated their acquisition of Latin. Students not only learned about culture but they also participated in it, interacting with other “inhabitants” of Rome. They not only read texts and created compositions, they also interacted in real time using Latin as the means of communication. This multimodal approach appealed to students because they could use the images, descriptions, and primary texts as prompts for language learning as they walked through the ancient city and interacted with each other. In short, the MOO provided students with a valuable resource that motivated them to integrate language and culture. While we lacked the technology to send students back to ancient Rome, we were able to use the Web to create multisensory environments where they could improve their understanding of ancient Romans and their language. 326 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Appendix A Directions to Treasure Hunt VRoma Treasure Hunt, Latin 102 Part I i Romam. deinde, procede ad regionem VIII (preme numerum VIII in mappa XIV regionum). deinde, ambula in Via Sacra et in Argileto. tandem, intra porticum senatus. 1. quaere vestimentum. quid est nomen vestimenti? quale est? quis id gerit? 2. i ad gradus curiae, deinde ad curiam. quid vides? quid est nomen apparatus? quis in hoc sedet? 3. mitte magistro electronica responsa. Part II i Romam. deinde, procede ad regionem VIII (preme numerum VIII in mappa XIV regionum). deinde, i ad rostra. 1. cur monumentum ‘rostra’ appellat? quis orationes hic habebat? 2. inveni scripta de rebus publicis. quid Cicero de Antonio dixit? quis Ciceronem occidit? quomodo Cicero perit? Vocabulary: cadere ‘fall’; detruncare ‘cut, sever’; venenum bibere ‘drink poison’; sibi mortem consciscere ‘commit suicide’ 3. mitte magistro electronica responsa. Part III i Romam. deinde, procede ad regionem VIII (preme numerum VIII in mappa XIV regionum). deinde, i ad rostra. 1. quae clara avis prope rostra habitabat? quid avis faciebat? quis avem occidit? cur? 2. procede ad monumentum avis. ubi est monumentum? quid in monumento inscriptum est? 3. estne fabula vera an falsa? 4. mitte magistro electronica responsa. Part IV i Romam. deinde, procede ad regionem IX (preme numerum IX in mappa XIV regionum). i ad theatrum Marcelli. (Marcellus nepos Augusti erat). 1. procede ad porticum vomitoriumque. quis supra sedet in cavea? quis infra sedet? quis sedet in orchestra? 2. quot ianuae sunt in scaenae fronte? 3. quid est magnificior? Theatrum Marcelli aut Circus Maximus aut Thermae Trajani? quod aedificium poterat plurimos homines continere? 4. mitte magistro electronica responsa. Volume 18 Number 2 327 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Appendix B Indicium (Clue) Oxford Latin Course, Ch 35 Argus occisus est! Quis? Ubi? Quomodo? Leges ludi Before class: · You will receive a dossier that indicates who your character will be, gives you several clues, and explains where you will begin the game. · Complete the chart in the Tabula Indiciorum by writing the accusative and ablative form of each word. This will help you make suggestions more quickly. · Write a brief description of your character in Latin. Before the game begins: · Your character name is the Latin word followed by Roman numeral of your group, e.g., ancillaI or uxor_ianitorisIV. There can be no spaces in a character name on the MOO. Do not use your real name as part of your character name. · Customize yourself (@rename me as/@describe me as) using the description you have already prepared. Be sure to end the description by giving your real name. · Meet the other characters in the location specified in your dossier. · Introduce your character to the rest of the group, e.g., “salvete. ancilla sum, puella ingeniosa.” · Remember, you can only talk to people in the same room. · Do not begin the game until everyone has introduced her/himself. Definitions: · A suggestion is a statement that indicates the killer, place, and implement of death. It begins with the word “credo.” · An accusation is a statement that indicates the killer, place, and implement of death. It begins with the word “accuso.” One must summon the magister/ra ludi for the accusation to be verified. · If an accusation is incorrect, the character who made the accusation may continue to take a turn as a verifier of a suggestion, but cannot make further suggestions or accusations. · If an accusation is completely correct, the character who made the correct accusation is the winner and the game is over. · For an accusation to be completely correct, it must not only identify the killer, place, and implement of death, but it must also be grammatically correct. 328 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton To play the game: · The ancilla makes the first suggestion upon entering the room she believes was the scene of the crime, e.g., “credo: Argus in apodyterio a caupone occisus est fune.” (I believe: Argus was killed by the innkeeper in the apodyterium with a rope.) · Characters make suggestions in alphabetical order. · Characters may only make a suggestion in the room they think is the location of the deed. · If it is your turn to make a suggestion and you decide to change rooms, inform the rest of the group where you are going, e.g., me sequimini ad aedem Iovis Optimi Maximi. While the rest of the group follows, you can begin to type your suggestion. Others can follow you by typing @join charactername. · Once a suggestion has been made, characters indicate if they have a clue in alphabetical order beginning with the character who comes next after the one who made the suggestion. Therefore, the botularius indicates first whether he has one of the clues, e.g., “funem habeo.” (I have the rope) or “indicium non habeo.” (I don’t have a clue.) If you have more than one of the suggested clues, you need only reveal one. · Once one character has indicated that s/he has a clue, then it is time for the next character to make a suggestion, i.e., the botularius. TABULA INDICIORUM BATHS OF TRAJAN Accusative Ablative Dramatis Personae ancilla -ae, F., maid botularius -ii, M., sausage-seller caupo -onis, M., innkeeper matrona -ae, F., married woman miles militis, M., soldier uxor ianitoris, F., wife of the doorkeeper Instrumenta mortis funis -is, M., rope gladius -ii, M., sword pugio -onis, M., dagger retia -ium, N. Pl., nets, traps saxa -orum, N. Pl., rocks tegula -ae, F., roof tile venenum -i, N., poison Loca facti: Balneae (Reg. III): apodyterium calidarium Volume 18 Number 2 329 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? frigidarium natatio nymphaeum palaestra quadrata palaestra rotunda tepidarium Indicium, adapted for VRoma by John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton, Cornell College Appendix C Quaere! Oxford Latin Course, Ch 26 Leges Ludi Before class: You will receive a dossier that indicates who your character will be and explains where you will begin the game (your homeroom). You will also be given a list of your team members and a list of five sets of objects and five rooms in which to play the game. Write a brief description of your character in Latin. Before the game begins: · Your character name is the Latin word followed by Roman numeral of your group, e.g., ancillaI or uxor_ianitorisIV. There can be no spaces in a character name on the MOO. Do not use your real name as part of your character name. · Customize yourself (@rename me as/@describe me as) using the description you have already prepared. Be sure to end the description by giving your real name. · Meet the other characters in the location specified in your dossier. · Introduce your character to the rest of the group, e.g., “salvete. ancilla sum, puella ingeniosa.” · Remember, you can only talk to people in the same room. · Do not begin the game until everyone has introduced her/himself. The Object of the Game: · The object of the game is to work together with your team to get each set of objects in the appropriate room. The game combines interaction in Latin with Roman culture. You need to determine (by conversing in Latin) which set of objects are culturally appropriate for the 330 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton room you are assigned (your homeroom) and which are appropriate for the common room. In other words, if you are assigned the rostra as your homeroom, you might choose to collect the set of orators since rostra is the speaker’s platform. Each person will begin the game by picking up two objects (take [object]). Other objects are scattered throughout your site. To Play the Game: · You may carry only two objects at a time. You can either trade with a person (give [obj] to [player]) or leave an object you are carrying (drop [object]) and pick up a new one (take [object]). · You should always have at least one object in your possession. If you put one down, you need to pick up another or trade for another until all the objects are picked up and put into the appropriate rooms. After you have collected the set of objects appropriate for your homeroom and dropped them there, then proceed to the common room with the remaining object. The game is over when everyone meets there, each carrying an object from the remaining set. · When you encounter a teammate, greet them, e.g. “salve, ancilla” and ask each other which objects each person is carrying, e.g., “botulum quaero. quid fers?” or “quid habes?” The ancilla may respond: “botulum et pilam habeo.” If one of you has an object the other one needs, you can offer to trade: “frigidam aquam pro botulo tradam.” If neither has a needed object, you can ask if they saw it “botulum vidisti?” The response could be either that you saw it in a certain room “botulum in apodyterio vidi” or you saw someone carrying it “ancillam botulum portantem vidi.” · Only you can put culturally appropriate objects into your homeroom. For example, if you are the ancilla and you have been assigned the apodyterium, only you can put vestimenta there. Any item, however, can be dropped in any room temporarily when exchanging it for another that no one is carrying. · Only two people can be in a room at the same time. If you enter a room where two people are already present, either you or someone else must leave before a transaction can occur. · Once the group thinks that all the objects are in their appropriate rooms and has met in the common room, call the magister/ra to find out if you are correct. QUAERE! BATHS OF TRAJAN (REG. III) Accusative Ablative Dramatis Personae Ancilla -ae, F., maid Volume 18 Number 2 331 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Botularius -ii, M., Sausage-seller Athleta -ae, M., athlete Puer -i, M., child Res aqua frigida -ae, F., cold water plumbum -I, N., lead weight botulus -I, M., sausage pila -ae, F., ball vestimenta -orum, N. Pl., clothes Loca apodyterium (A) -ii, N., changing room atrium -ii, N., entrance frigidarium -ii, N., cold room natatio -onis, F., swimming pool palaestra -ae, F., wrestling ground APPENDIX D Evaluation, Latin 102, February 2000 TECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE. Assess your abilities using technology at the end of the course, using a 0-5 scale where 0 means no knowledge and 5 means excellent. Feel free to make comments wherever relevant. After the Course (0-5) 1. Using E-mail (read, send, reply) 2. Using Cornell’s E-mail, Outlook Express (read, send, reply) 3. Opening Netscape 4. Reaching a site by typing an address 5. Reaching a site by clicking on a link 6. Logging onto a MOO/MUD 332 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton 7. Viewing rooms and objects in a MOO 8. Moving from room to room or place to place in a MOO 9. Activating characters in a MOO 9. Speaking to others in a MOO 10. Customizing yourself/character in a MOO 11. Picking up and dropping objects 12. Exchanging objects BACKGROUND. How many times did you participate in each activity: 1. MOO orientation session (visiting the Baths of Trajan and Circus Maximus) 0 1 2 2. Vroma Treasure Hunt 0 1 2 3. Clue 0 1 2 4. Quaere! 0 1 2 CONTENT. Assess the impact of technology, especially VRoma, on improving your understanding of the Latin language and Roman culture, using a 0-5 scale where 0 means not at all and 5 means very much. Then list the type of information that most helped in each area (see below), as many as are relevant. End of Course 0-5 Type of info (a-g) 1a. Vroma Treasure Hunt activities helped me understand Latin grammar 1b. Vroma Clue activities helped me understand Latin grammar Volume 18 Number 2 333 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? 1c. Vroma Quaere activities helped me understand Latin grammar 2a. Vroma Treasure Hunt activities helped me improve Latin vocabulary 2b. Vroma Clue activities helped me improve Latin vocabulary 2c. Vroma Quaere activities helped me improve Latin vocabulary 3a. Vroma Treasure Hunt activities helped me understand Roman culture 3b. Vroma Clue activities helped me understand Roman culture 3c. Vroma Quaere activities helped me understand Roman culture 4a. Vroma Treasure Hunt activities helped me read Latin 4b. Vroma Clue activities helped me read Latin 4c. Vroma Quaere activities helped me read Latin 5a. Vroma Treasure Hunt activities helped me write Latin 5b. Vroma Clue activities helped me write Latin 5c. Vroma Quaere activities helped me write Latin 6a. Vroma Treasure Hunt activities interact in Latin 6b. Vroma Clue activities helped me interact in Latin 6c. Vroma Quaere activities helped me interact in Latin 7. In short, Vroma activities helped me understand Latin better 334 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Types of information in the MOO a. Textual description b. Images c. Viewing objects, such as the sella curulis or toga praetexta d. Becoming another character/customizing yourself e. Meeting talking Arobots,@ such as Antoninus Pius or Cornelia f. Conversing with other students on the MOO g. Entering a virtual world where you could make use of many media/ ways to learn FUTURE. Please share your comments and suggestions. Please use back. 1. What was the biggest benefit of using the MOO? 2. What was the biggest challenge in using the MOO? 3. In what way could the VRoma experience be improved? Volume 18 Number 2 335 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? REFERENCES American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. (1996). Standards for foreign language learning: Preparing for the 21st century. Yonkers, NY: National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project. On-line document available: www.actfl.org Balme, M., & Morwood, J. (1996). Oxford Latin Course (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press. Beauvois, M. H. (1992). Computer-assisted classroom discussion in the classroom: Conversation in slow motion. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 455-64. Beauvois, M. H. (1997). Computer-mediated communication (CMC): Technology for improving speaking and writing. In M. D. Bush & R. M. Terry (Eds.), Technology-enhanced language learning (pp. 165-184). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook. Crawford-Lange, L. M., & Lange, D. L. (1984). Doing the unthinkable in the second-language classroom: A process for the integration of language and culture. In T. V. Higgs (Ed.), Teaching for proficiency, the organizing principle (pp. 139-177). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook. Devitt, S. (1997). Interacting with authentic texts: Multilayered processes. Modern Language Journal, 81, 457-469. Ellis, R. (1984). Classroom second language development: A study of classroom interaction and language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Gascoyne, R., et al. (1997). Standards for classical language learning. Oxford OH: American Classical League. Hall, J. K., & Ramirez, A. (1993). How a group of high school learners of Spanish perceives the cultural identities of Spanish speakers, English speakers, and themselves. Hispania, 76, 613-620. Hanvey, R. G. (1979). Cross-cultural awareness. In E. C. Smith & L. F. Luce (Eds.), Toward internationalism: Readings in cross-cultural communication. (pp. 46-56). Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lee, S., Groves, P., Stephens, C., & Armitage, S. (1999). Guide to online teaching: Existing tools and projects: MUDs, MOOs, WOOs and IRC (JTAP Reports) [On-line]. Available: www.jtap.ac.uk/reports/htm/jtap-028-5.html Le MOO français. (2000, August). Available: www.umsl.edu/~moosproj/ moofrancais.html Little Italy. (2000, August). Available: kame.usr.dsi.unimi.it:4444 MOOsaico. (2000, August). Available: moo.di.uminho.pt:7777/ Mugit. (2000, August). Available: www.ipa.net/~magreyn/mugit.htm MundoHispano. (2000, August). Available: www.umsl.edu/~moosproj/mundo.html Nobuyoshi, J., & Ellis, R. (1993). Focused communication tasks and second language acquisition. ELT Journal, 47, 203-10. 336 CALICO Journal John Gruber-Miller and Cindy Benton Pfister, G. G., & Borzilleri, P. (1977). Surface culture concepts: A design for the evaluation of cultural materials in textbooks. Unterrichtspraxis, 10, 102108. Pica, T. (1994). Research on negotiation: What does it reveal about second language learning conditions, processes, and outcomes? Language Learning, 44, 493-527. Pica, T., Holliday, L., Lewis, N., & Morgenthaler, L. (1989). Comprehensible output as an outcome of linguistic demands on the learner. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 11, 63-90. Pica, T., Kanagy, R., & Falodun, J. (1993). Choosing and using communicative tasks for second language instruction. In G. Crookes & S. M. Gass (Eds.), Tasks and language learning: Integrating theory and practice. Clevedon, ENG: Multilingual Matters. Rawson, E. (1987). Discrimina ordinum: The lex Julia theatralis. Papers of the British School at Rome, 55, 83-114. Richlin, A. (1999). Cicero’s head. In J. I. Porter (Ed.), Constructions of the classical body (pp. 190-211). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. Robinson-Stuart, G., & Nocon, H. (1996). Second culture acquisition: Ethnography in foreign language classroom. Modern Language Journal, 80, 431449. Sanchez, B. (1996). MOOving to a new frontier in language learning. In M. Warschauer (Ed.), Telecollaboration in foreign language learning. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center. Schwienhorst, K. (1998a). Co-constructing learning environments and learner identities—language learning in virtual reality [On-line]. Available: www.tcd.ie/CLCS/assistants/kschwien/Publications/coconstruct.htm Schwienhorst, K. (1998b). The ‘third place’—virtual reality applications for second language learning [On-line]. Available: www.tcd.ie/CLCS/assistants/ kschwien/Publications/eurocall97.htm SchMOOze. (2000, August). Available: schmooze.hunter.cuny.edu:8888/ Seelye, H. N. (1984). Teaching culture: Strategies for intercultural communication. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company. Shield, L., Weininger, M. J., & Davies, L. B. (1999). MOOs and language learning [On-line]. A vailable: www.enabling.org/grassroots/languagelearning.html Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for the implementation of task-based instruction. Applied Linguistics, 17, 38-62. Steele, R. (1990). Culture in the foreign language classroom. ERIC/CLL News Bulletin, 14, 4-5. Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step towards second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 16, 371-91. Volume 18 Number 2 337 How do You Say “MOO” in Latin? Turbee, L. (1996). MOOing in a foreign language: How, why, and who? [On-line]. Available: home.twcny.rr.com/lonnieturbee/itechtm.html Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. Modern Language Journal, 81, 470-81. Warschauer, M. (Ed.). (2000). Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice. Cambridge, ENG: Cambridge University Press. Zanker, P. (1988). The power of images in the age of Augustus (A. Shapiro, Trans.). Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. AUTHORS’ BIODATA John Gruber-Miller is Professor of Classics at Cornell College, Mt. Vernon, Iowa. In addition to being a core faculty member of the VRoma Project, he is the author of Scriba, Software to accompany the Oxford Latin Course, Part 1 and the site maintainer for the Riley Collection of Roman Portrait Sculptures (www.vroma.org/~riley/). Finally, he is editing When Dead Tongues Speak: Teaching Beginning Greek and Latin (forthcoming), a volume that explores ways of teaching Latin and Greek using collaborative and communicative approaches. Cindy Benton is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics at Cornell College, Mt. Vernon, Iowa. She is a member of the VRoma Project and author of “Split Vision: The Politics of the Gaze in Seneca’s Troades” in The Roman gaze: Vision, power and the body in Roman society (forthcoming). AUTHORS’ ADDRESS John Gruber-Miller Classical and Modern Languages Cornell College 600 First Street West Mt. Vernon, IA 52314 Phone: 319/895-4326 Fax: 319/895-4492 E-mail: jgruber-miller@cornell-iowa.edu Cindy Benton Classical and Modern Languages Cornell College 600 First Street West Mt. Vernon, IA 52314 Phone: 319/895-4126 Fax: 319/895-4492 E-mail: cbenton@cornell-iowa.edu 338 CALICO Journal