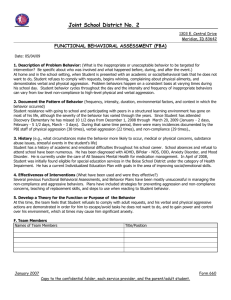

as a PDF

advertisement