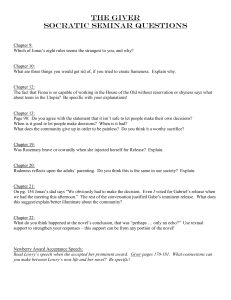

Individual and Societal Control in Lois Lowry's The Giver

advertisement