RBI's Wilful Defaulter Circular: All director's

advertisement

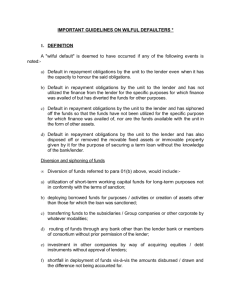

CORPORATE LAWS RBI’s Wilful Defaulter Circular: All director's painted with the same brush An analysis of Ionic Metalliks v. Union of India [2014] 49 taxmann.com 222 (Guj.) &+1/,!2 1&,+ 1. All scheduled commercial banks (excluding RRBs and LABs) and All India Notified Financial Institutions are empowered vide the RBI Master Circular1 (“Master Circular”) dated 2-7-2012 to list its borrowers upon fulfilment of any of the conditions laid down in clause 2.1 of the Master Circular, as wilful defaulters and thereby to stop any future financial assistance to them.‘Wilful default’ is defined in clause 2.1 of the Master Circular as follows: GAURAV ARORA $VVRFLDWH -6DJDU$VVRFLDWHV ABHINAV MISHRA “A wilful default would be deemed to have occurred if any of the following events is noted:(a) The unit has defaulted in meeting its payment/repayment obligations to the lender even when it has the capacity to honour the said obligations. (b) The unit has defaulted in meeting its payment/repayment obligations to the lender and has not utilised the finance from the lender for the specific September 16 To 30, 2014 Taxmann’s Corporate Professionals Today Vol. 31 62 purposes for which finance was availed of but has diverted the funds for other purposes. (c) The unit has defaulted in meeting its payment/repayment obligations to the lender and has siphoned off the funds so that the funds have not been utilised for the specific purpose for which finance was availed of, nor are the funds available with the unit in the form of other assets. (d) The unit has defaulted in meeting its payment/repayment obligations to the lender and has also disposed off or removed the movable fixed assets or immovable property 6 DBOD – MC on Wilful Defaulters – 2014 given by him or it for the purpose of securing a term loan without the knowledge of the bank/lenders.” As per clauses 5.1 and 5.2 (reproduced in the later part of this case analysis) of the Master Circular, the Reserve Bank of India (“RBI”) has extended the scope of classification as wilful defaulter to all the directors and promoters/entrepreneurs of the defaulting company. The consequence of being classified as a wilful defaulter in case of the directors, as per clause 2.5(d)2 of the Master Circular, entails them being ousted from the board of any other borrowing company. As per clause 2.5(a)3 of the Master Circular, the promoters/ entrepreneurs can be debarred from seeking institutional financial assistance for floating new ventures for a period of 5 years. In the light of an increasing number of wilful defaults by companies, such as the Kingfisher Airlines and a strong need to strengthen the corporate governance regime, the judgment by a two Judge Bench of the Gujarat High Court (“Court”) in Ionic Metalliks v. Union of India4 (“Ionic Metalliks Case”), dated September KDV EHFRPH FUXFLDO ï ILUVWO\ WR WKH banks and financial institutions, whose scope to categorize certain borrowers as wilful defaulters has been held to be constitutional; and secondly, to the directors of the defaulting companies, who can no longer be held liable without due regard being paid to their type and control in the company’s decision-making which may have led to the default. # 12)+)60&0,#IONIC METALLIKS 0" 2. The petitioners, in the instant case, had availed of loan facilities from the respondents, Punjab National Bank and Standard Chartered Bank, respectively. Shortly thereafter all of the three bank loans were declared as Non Performing Assets (NPA) by the Respondentbanks on the ground of wilful default in payment and siphoning off of funds, and, subsequently, show-cause notices were served on the petitioners as per the Master Circular. Additionally, a notice under section 13(4) of the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 (which states the possible recourse which can be taken against a defaulting borrower) was served by the Standard Chartered Bank upon the petitioners. Thereafter, the petitioners filed a Special Civil Application in the Gujarat High Court, praying that: (a) the RBI Master Circular, dated July 2, 2012 be declared ultra vires the Constitution of India, 1950 (“Constitution”) and/or the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 and/or the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and/or the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and/ or the Recovery of Debts Due to Bank and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 and/or the Credit Information Companies (Regulation) Act, 2005 and/or the Indian Contract Act; (b) the notice issued to the petitioners be quashed for the reason that it was bereft of any reasons and necessary particulars for listing the petitioners as wilful defaulters. 2.1 Issues before the division bench of the Gujarat High Court 2.1.1 Master Circular constitutionally valid in general terms: The two Judge Bench while dealing September 16 To 30, 2014 Taxmann’s Corporate Professionals Today Vol. 31 63 CORPORATE LAWS with the first contention of the Petitioners, held that insofar as the constitutionality of the Master Circular was concerned, the same did not suffer from the lack of power under Article 19(1)(g) that was ‘the right to carry on any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business’ for the reason that no borrower wilfully failed to make payments and was able to claim an inherent right to seek financial assistant from a bank and, therefore, was intra vires the Constitution. The Court while relying on Md. Murtaza v. State of Assam5, noted as follows: “It (Master Circular) targets defaulters of dues in excess of `25 lakh, thus laying down the threshold limit for application of the circular. It applies to only those defaulters who can be categorized as ‘wilful’ as defined in the circular. It, thus, does not cover those borrowers who are unable to pay the debt without there being any element of wilfulness. Surely, no borrower can claim a vested right to seek financial assistance from a bank or a financial institution no matter how wilful or chronic his defaults in repayment of past dues may have been. The circular, therefore, in general terms, is not arbitrary. (Emphasis supplied).” Further, it strengthened the view that the Master Circular contained adequate safeguards for ensuring transparency and minimizing discretionary powers of banks and financial institutions in the entire manner of recovery of debt and stated that an enactment could not be struck down on the mere possibility of abuse of power. 2.1.2 Master Circular partially unconstitutional: The Court stated that the Master Circular, insofar as it brought all the directors (not being the promoters/entrepreneurs) regardless of their type under its purview for declaring them as wilful defaulters vide clauses 5.1 and 5.2, sought to oust them from the board of any borrowing company, was arbitrary and even the nominee and independent directors (who may not have the same amount of control as other directors in the decisions of the company leading to the wilful default), cannot be held to be uniformly liable for the same. Clauses 5.1 and 5.2 of the Master Circular have been reproduced below: “5.1 Need for Ensuring Accuracy RBI/Credit Information Companies disseminate information on non-suit filed and suit filed accounts, respectively, as reported to them by the banks/FIs and responsibility for reporting correct information and also accuracy of facts and figures rests with the concerned banks and financial institutions. Therefore, banks and financial institutions should take immediate steps to update their records and ensure that the names of current directors are reported. In addition to reporting the names of current directors, it is necessary to furnish information about directors who were associated with the company at the time the account was classified as defaulter, to put the other banks and financial institutions on guard. Banks and FIs may also ensure the facts about directors, wherever possible, by crosschecking with Registrar of Companies. 5.2 Position regarding Independent and Nominee directors Professional Directors who associate with companies for their expert knowledge act as independent directors. Such independent directors apart from receiving director’s remuneration do not have any material pecuniary relationship or transactions with the company, its promoters, its management or its subsidiaries, which in the judgment of Board may affect their independent judgment. As a guiding principle of disclosure, no material fact should be suppressed while disclosing the names of a company, that is a defaulter and the names of all directors should be published. However, while doing so, a suitable distinguishing remark should September 16 To 30, 2014 Taxmann’s Corporate Professionals Today Vol. 31 64 be made clarifying that the concerned person was an independent director. Similarly, the names of directors who are nominees of government or financial institutions should also be reported but a suitable remark ‘nominee director’ should be incorporated. Therefore, against the names of Independent Directors and Nominee Directors, they should indicate the abbreviations “Ind” and “Nom”, respectively, in brackets to distinguish them from other directors.” The Court rightly observed on the point of ‘painting all the directors with the same brush’ as under: “This provision in the circular shatters the concept of the identity of a company different and distinct from its directors without providing any safeguards. It does not distinguish between a director who is involved in the day-to-day functioning of a company as against those who are not. The circular paints all directors with the same brush. Therefore, we have reached to a conclusion that the Master Circular, so far as it is sought to be made applicable to all the directors of the company is arbitrary and unreasonable.” (Emphasis supplied). 2.1.3 Master Circular and principles of natural justice: Rejecting the submission of the petitioners that if the RBI was to lay down a policy declaring borrowers as wilful defaulters and the consequences of the same, it should have done so by enacting a law within Article 13 of the Constitution; and that if the Master Circular was made in public interest then it should have stated so in the requisite wordings, the Court stated that the RBI derives its power to frame a legislation, such as the impugned Master Circular (which seeks to regulate the affairs of banks and financial institutions in the country so far as the law permits it to), by the virtue of sections 21 and 35A of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 which allow it to control the advances of, and to give directions to, the banks and financial institutions which come under its purview. Further, the Legislature may delegate the authority to frame such legislation on a body such as the RBI which has considerable expertise in such financial matters. The Court, relying on the Supreme Court’s decision in Union of India v. Azadi Bachao Andolan6, stated that it is a settled position of law that so long as the powers of an authority are traceable to a source, it is not binding upon the authority to indicate the same in an instrument framed by it and the same would not infringe the principles of natural justice. Placing reliance upon the Supreme Court’s decision in Joseph Kuruvilla Vellukunnel v. Reserve Bank of India7, it noted as under: “The law is well-settled that the Reserve Bank of India, which is described as the supreme bank of the country, is empowered to regulate the banking system and certain regulatory functions have been assigned to it by the provisions of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 and the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. It is in exercise of such powers that the Reserve Bank of India has thought fit to issue the impugned Master Circular.” 2.1.4 Show-cause notice vague, unreasonable and liable to be quashed in principle: The Court while dealing with the issue of the validity of the notices served upon the petitioners by the respondents opined that the showcause notices were vague and contained no reasons for classifying the petitioners as wilful defaulters. Quashing the notice issued by the Punjab National Bank and allowing it to file a fresh show-cause notice, it noted as under: “The show-cause notice is absolutely vague and contains no factual or other materials. We fail to understand on what basis the bank has alleged in the showcause notice that the funds provided by the bank have been siphoned off and the same were used for the purpose other than the project for which the loan was sanctioned. If such are the nature of the September 16 To 30, 2014 Taxmann’s Corporate Professionals Today Vol. 31 65 CORPORATE LAWS allegations, then at least it is expected of the bank to provide some materials so that the petitioners can meet with the same. It has to be held that there is violation of the principles of natural justice. One of the facets of the principles of natural justice is fairness which, we do not find on the part of the bank in the proposed action.” However, in contemplating over whether it had writ jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution over Standard Chartered Bank which happened to be a private bank, placing reliance upon the tests devised by the Apex Court in its decision in Ajay Hasia v. Khalid Mujib8, reiterated in Jatyapal Singh v. Union of India9 and Federal Bank Ltd. v. Sagar Thomas10, to determine whether a private bank falls under the writ jurisdiction of the High Court, the Court held that it did not have the writ jurisdiction over Standard Chartered Bank in order to quash the show-cause notice issued by it for the reason the bank in question, being private in nature, was not an agency and instrumentality of the State and could not be considered an ‘authority’ under Article 12 of the Constitution. Further, it stated that the Standard Chartered Bank could not be said to be a private body performing a public duty as it was not empowered to take actions affecting the public. It suggested to the petitioners to take recourse to the appropriate judicial authority in order to furnish their grievance regarding the invalidity of the impugned show-cause notice. ,+ )20&,+ 3. From the perspective of empowering the banks and financial institutions to recover bad debts from wilful defaulters, the Ionic Metallik case (supra) is a landmark judgment in the sense that it constitutionally validates the power of the RBI to frame legislations such as the Master Circular in the instant case. Even though the question regarding the constitutional validity of the Master Circular had arisen previously in the case of Kotak Mahindra Bank Ltd. v. Hindustan National Glass & Industries Ltd.11, yet the Supreme Court declined to decide the same as it was not raised during the proceedings in the High Court. The practical outcome of this Judgment, as regards imputability of all directors in the Master Circular, is doubtful considering that in the past banks have not necessarily listed all the directors on the board of the company to be liable. For instance, recently the United Bank of India listed only four of the directors of Kingfisher Airlines including Vijay Mallya as wilful defaulters. Thus, this judgment can be seen as largely in favour of the banks and financial institutions, as while strengthening their stand in declaring certain borrowers as wilful defaulters, what it merely requires them to do is to make an amendment to the Master Circular to the effect of not classifying all the directors as wilful defaulters, regardless of their type, which is not a heavy loss to the banks by any stretch of imagination. Perhaps the only real benefit derived from this judgment by the borrowing companies in the country is that the banks and financial institutions would now be dissuaded from serving show-cause notices upon those which are bereft of any reasons, reducing the scope for the banks and financial institutions to take illegal and arbitrary measures to protect their balance sheets. While the Ionic Metallik case (supra) answers some crucial questions, at the same time certain questions remain unanswered, making it unlikely that the litigation would stop at this juncture. The judgment is expected to have at least persuasive value on the private banks as well but what needs to be kept in mind is the possible alternative outcome of the judgment with respect to the show-cause notice of the Standard Chartered Bank, had the petitioners challenged its legal validity instead of the constitutional validity. What also remains to be seen is the effect of the Ionic Metallik case (supra) on the Guidelines September 16 To 30, 2014 Taxmann’s Corporate Professionals Today Vol. 31 66 on Wilful Defaulters12 issued by the RBI on September 9, 2014 which clarifies that the liability of guarantors is co-extensive with that of the borrowers and that they can be proceeded against even before exhausting the remedies against the borrowers. z zz - The views expressed are personal views of the authors. 1. ‘Master Circular on Wilful Defaulters’ RBI/2012-13/43DBOD No. CID.BC. 10/20.16.003/2012-13. 2. A covenant in the loan agreements, with the companies in which the banks/notified FIs have significant stake, should be incorporated by the banks/FIs to the effect that the borrowing company should not induct a person who is a promoter or director on the Board of a company which has been identified as a wilful defaulter as per the definition at paragraph 2.1 above and that in case, such a person is found to be on the Board of the borrower company, it would take expeditious and effective steps for removal of the person from its Board. 3. No additional facilities should be granted by any bank/FI to the listed wilful defaulters. In addition, the entrepreneurs/promoters of companies where banks/FIs have identified siphoning/diversion of funds, misrepresentation, falsification of accounts and fraudulent transactions should be debarred from institutional finance from the scheduled commercial banks, Development Financial Institutions, Government owned NBFCs, investment institutions etc. for floating new ventures for a period of 5 years from the date the name of the wilful defaulter is published in the list of wilful defaulters by the RBI. 4. [2014] 49 taxmann.com 222 (Guj.). 5. 2011(9) SCALE 526. 6. [2004] 10 SCC 1. 7. AIR 1962 SC 1371. 8. AIR 1981 SC 487. 9. [2013] 6 SCC 452. 10. [2003] 10 SCC 733. 11. [2013] 117 SCL 521/[2012] 28 taxmann.com 140 (SC). 12. ‘Guidelines on Wilful Defaulters – Clarification regarding Guarantor, Lender and Unit’,RBI/2014-15/221DBOD.No.CID. 41/20.16.003/2014-15. September 16 To 30, 2014 Taxmann’s Corporate Professionals Today Vol. 31 67