Neuromuscular Disorders 19 (2009) 714–717

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Neuromuscular Disorders

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/nmd

Case report

Congenital monomelic muscular hypertrophy of the upper extremity

H. Jacobus Gilhuis a,*, Oliver T. Zöphel b, M. Lammens c, Machiel J. Zwarts c

a

Department of Neurology, Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft, The Netherlands

Department of Plastic Surgery, Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands

c

Neuromuscular Center Nijmegen, Departments of Pathology, Neurology, and Clinical Neurophysiology, University Medical Centre St Radboud, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 April 2009

Accepted 8 July 2009

Keywords:

Biopsy

Hand

Muscular hypertrophy

a b s t r a c t

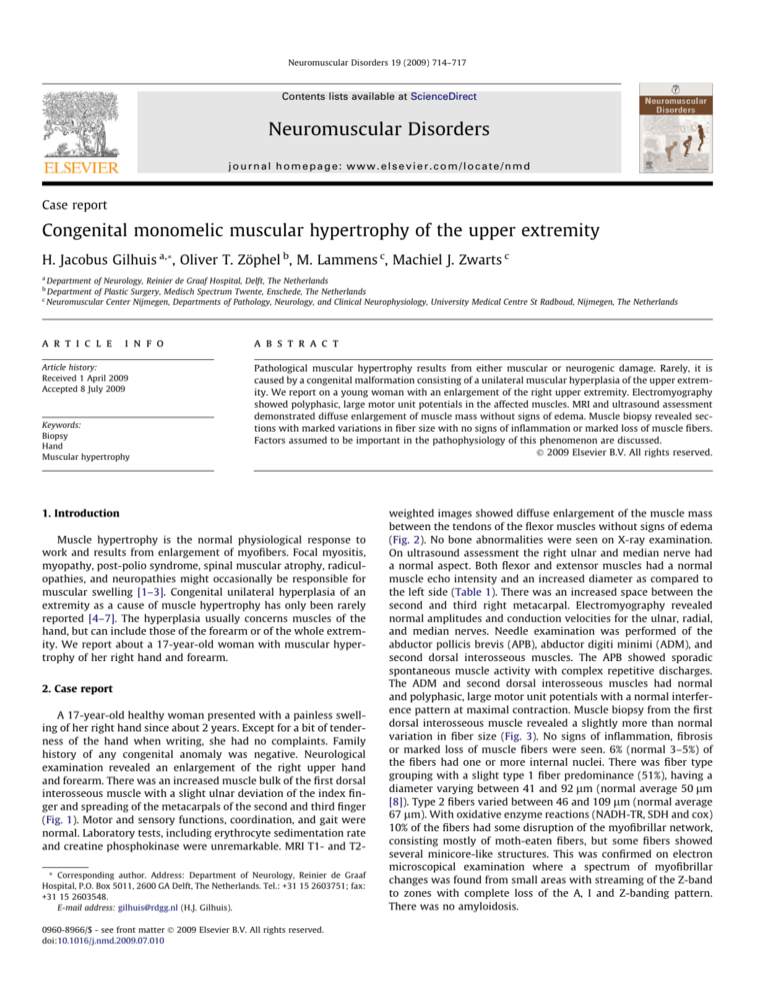

Pathological muscular hypertrophy results from either muscular or neurogenic damage. Rarely, it is

caused by a congenital malformation consisting of a unilateral muscular hyperplasia of the upper extremity. We report on a young woman with an enlargement of the right upper extremity. Electromyography

showed polyphasic, large motor unit potentials in the affected muscles. MRI and ultrasound assessment

demonstrated diffuse enlargement of muscle mass without signs of edema. Muscle biopsy revealed sections with marked variations in fiber size with no signs of inflammation or marked loss of muscle fibers.

Factors assumed to be important in the pathophysiology of this phenomenon are discussed.

Ó 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Muscle hypertrophy is the normal physiological response to

work and results from enlargement of myofibers. Focal myositis,

myopathy, post-polio syndrome, spinal muscular atrophy, radiculopathies, and neuropathies might occasionally be responsible for

muscular swelling [1–3]. Congenital unilateral hyperplasia of an

extremity as a cause of muscle hypertrophy has only been rarely

reported [4–7]. The hyperplasia usually concerns muscles of the

hand, but can include those of the forearm or of the whole extremity. We report about a 17-year-old woman with muscular hypertrophy of her right hand and forearm.

2. Case report

A 17-year-old healthy woman presented with a painless swelling of her right hand since about 2 years. Except for a bit of tenderness of the hand when writing, she had no complaints. Family

history of any congenital anomaly was negative. Neurological

examination revealed an enlargement of the right upper hand

and forearm. There was an increased muscle bulk of the first dorsal

interosseous muscle with a slight ulnar deviation of the index finger and spreading of the metacarpals of the second and third finger

(Fig. 1). Motor and sensory functions, coordination, and gait were

normal. Laboratory tests, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate

and creatine phosphokinase were unremarkable. MRI T1- and T2* Corresponding author. Address: Department of Neurology, Reinier de Graaf

Hospital, P.O. Box 5011, 2600 GA Delft, The Netherlands. Tel.: +31 15 2603751; fax:

+31 15 2603548.

E-mail address: gilhuis@rdgg.nl (H.J. Gilhuis).

0960-8966/$ - see front matter Ó 2009 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2009.07.010

weighted images showed diffuse enlargement of the muscle mass

between the tendons of the flexor muscles without signs of edema

(Fig. 2). No bone abnormalities were seen on X-ray examination.

On ultrasound assessment the right ulnar and median nerve had

a normal aspect. Both flexor and extensor muscles had a normal

muscle echo intensity and an increased diameter as compared to

the left side (Table 1). There was an increased space between the

second and third right metacarpal. Electromyography revealed

normal amplitudes and conduction velocities for the ulnar, radial,

and median nerves. Needle examination was performed of the

abductor pollicis brevis (APB), abductor digiti minimi (ADM), and

second dorsal interosseous muscles. The APB showed sporadic

spontaneous muscle activity with complex repetitive discharges.

The ADM and second dorsal interosseous muscles had normal

and polyphasic, large motor unit potentials with a normal interference pattern at maximal contraction. Muscle biopsy from the first

dorsal interosseous muscle revealed a slightly more than normal

variation in fiber size (Fig. 3). No signs of inflammation, fibrosis

or marked loss of muscle fibers were seen. 6% (normal 3–5%) of

the fibers had one or more internal nuclei. There was fiber type

grouping with a slight type 1 fiber predominance (51%), having a

diameter varying between 41 and 92 lm (normal average 50 lm

[8]). Type 2 fibers varied between 46 and 109 lm (normal average

67 lm). With oxidative enzyme reactions (NADH-TR, SDH and cox)

10% of the fibers had some disruption of the myofibrillar network,

consisting mostly of moth-eaten fibers, but some fibers showed

several minicore-like structures. This was confirmed on electron

microscopical examination where a spectrum of myofibrillar

changes was found from small areas with streaming of the Z-band

to zones with complete loss of the A, I and Z-banding pattern.

There was no amyloidosis.

H.J. Gilhuis et al. / Neuromuscular Disorders 19 (2009) 714–717

715

Fig. 1. (Right hand) Notice the increased muscle bulk of the first dorsal interosseous muscle, the ulnar deviation of the index finger, and the spread of the second and third

metacarpals.

Fig. 2. MRI T1-weighted image of the both hands revealing diffuse enlargement of the muscles of the right hand.

716

H.J. Gilhuis et al. / Neuromuscular Disorders 19 (2009) 714–717

Table 1

Echo of both forearms.

Muscles

Side

Echo intensity

z-Score

Diameter

z-Score

Flexor forearm

Flexor forearm

Extensor forearm

Extensor forearm

Right

Left

Right

Left

44

36

37

41

0.0

1.3

0.0

0.0

2.76

2.11

1.52

1.28

2.2

0.5

0.0

0.0

Fig. 3. (A) Muscle biopsy with variation of fiber caliber and fibers with internal

nuclei (HE, bar = 100 lm). (B) Moth-eaten fibers and some fibers with small corelike structures (SDH, bar = 100 lm).

The clinical symptoms as well as the MRI abnormalities remained unchanged during a follow-up of 2 years.

3. Discussion

Muscular hyperplasia due to a congenital unilateral upper-limb

hypertrophy is a rare phenomenon. So far, only 11 clearly defined

cases have been described in the German and English medical literature [4–7] An additional eight cases have been reported in the

Japanese literature [7].The age of these patients from the German

and English literature ranged from 2 to 19 years. None of them

had a progressive course. Of these cases, three had only involvement of the hand, two of the hand and forearm, whereas the others

had involvement of the whole upper extremity, including the

shoulder. All patients, including the present case, had an ulnar

deviation of the fingers and an increased spread at the metacarpal

joints. None of them had a positive family history nor had any

other congenital abnormalities. Except for hypertrophy of the muscles, nine patients have aberrant muscles. So far, in only two other

cases histological examination of muscle tissue was performed

[6,7]. These biopsies did not reveal any abnormalities. In contrast,

the present case showed myopathic changes with especially alterations of the intermyofibrillar network.

Congenital unilateral muscular hyperplasia of an extremity is

distinctly different from other causes of hand or upper-limb hypertrophy. Proteus syndrome for example, a complex disorder comprising malformations and overgrowth, is characterized by a

progressive course of the abnormalities. In most cases, it is not confined to one extremity [9]. The windblown hand is a (usually) bilateral flexion and adduction contracture of the thumb and narrowing

of the first web space. In addition, there is a flexion contracture and

ulnar deviation of the fingers at the metacarpal joints [6]. Freeman–Sheldon syndrome, a type of distal arthrogryposis, involves

two or more features of distal arthrogryposis: microstomia, whistling-face, nasolabial creases, and ‘H-shaped’ chin dimple [10].

The fourth category, which can give hyperplasia of a limb, are

nerve hamartomas. However, they cause progressive growth, and

were excluded by MRI [6]. Finally, muscle hypertrophy following

nerve injury, so called neurogenic pseudo hypertrophy, is electromyographically characterized by excessive spontaneous discharges

and early recruitment of large motor unit potentials at a high firing

rate. The hypertrophy is restricted to muscles innervated by the

damaged nerve. Biopsy findings in these cases show small groups

of types I and II atrophic muscle fibers and abundant hypertrophic

fibers of mostly type II [2]. Congenital muscular hyperplasia has

never been described in the lower extremities.

The exact etiology of unilateral hyperplasia of the upper-limb remains undetermined. The wide range of age at presentation is probably due to the fact that some patients were not seriously hindered

in daily life. Takka et al. [6] claimed that a changed tendon to muscle

ratio and the increased number of neuromuscular junctions involved cause the hypertrophy of the muscles in these patients. Aberrant muscles, they suggest, might be the unused atrophied muscles

during the evolutionary change of the hand like the Palmaris brevis

muscle. Tanabe et al. [7] assumed that in their case, the deformity of

the hand was due to relaxation of the transverse metacarpal ligaments causing increased spread of the fingers. Imbalance of the

intrinsic muscles of the hand would have caused crossing of the index and middle finger. Although in the present case, the fiber type

grouping suggested a neurogenic origin, the hypertrophy was not

confined to a muscle group innervated by a specific peripheral nerve,

part of the brachial plexus, or nerve root. In addition, repeated MRIs

showed normal intensity of muscle tissue.

Treatment is difficult because of the complexity of the clinical

features. It consists of excision of aberrant and hypertrophic muscles for cosmetic reasons or to correct contractures, but is often not

satisfactory [4,7]. Maintenance of the proportional balance of

intrinsic and extrinsic muscles can become difficult [6]. Pillukat

et al. recommend an operation as early as possible to prevent contractures [4]. In the present case, we opted for a ‘wait and see’ policy, as she was not severely hindered in her daily life, and there

were no cosmetic problems.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Mrs. F. Oostrom for her secretarial support.

References

[1] Guttmann L. AAEM minimonograph #46: neurogenic muscle hypertrophy.

Muscle & Nerve 1996;19:811–9.

[2] Mattle HP, Hess CW, Ludin HP, Mumenthaler M. Isolated muscle hypertrophy

as a sign of radicular or peripheral nerve injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry

1991;54:325–9.

[3] Zabel JP, Peutot A, Chapuis D, Batch T, Lecocq J, Blum A. Neurogenic muscle

hypertrophy: imaging features in three cases and review of the literature. J

Radiol 2005;86:133–41 [in French].

H.J. Gilhuis et al. / Neuromuscular Disorders 19 (2009) 714–717

[4] Pillukat T, Lanz U. Congenital unilateral muscular hyperplasia of the hand – a

rare malformation. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 2004;36:170–8 [in German].

[5] So YC. An unusual association of the windblown hand with upper limb

hypertrophy. J Hand Surg 1992;17:113–7.

[6] Takka S, Kazuteru D, Hattory Y, Kitajima I, Sano K. Proposal of new category for

congenital unilateral upper limb muscular hypertrophy. Ann Plast Surg

2005;54:97–102.

[7] Tanabe K, Tada K, Doi T. Unilateral hypertrophy of the upper extremity due to

aberrant muscles. J Hand Surg 1997;22:253–7.

717

[8] Polgar J, Johnson MA, Weightman D, Appleton D. Data on fibre size in

thirty-six

human

muscles.

An

autopsy

study.

J

Neurol

Sci

1973;19:307–18.

[9] Satter E. Proteus syndrome: 2 case reports and a review of the literature. Cutis

2007;297:302.

[10] Stevenson DA, Carey JC, Palumbos J, Rutherford A, Dolcourt J, Bamshad MJ.

Clinical characteristics and natural history of Freeman–Sheldon syndrome.

Pediatrics 2006;117:754–62.