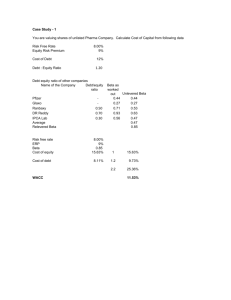

THE WEIGHTED AVERAGE COST OF CAPITAL A INTRODUCTION

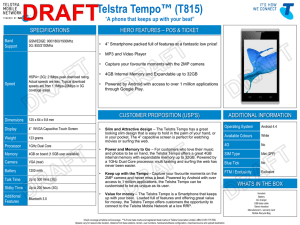

advertisement