(2000). Managerial performance development constructs and

advertisement

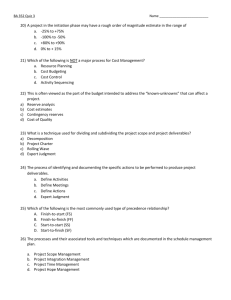

HUMAN PERFORMANCE, 13(1), 23–46 Copyright © 2000, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Managerial Performance Development Constructs and Personality Correlates James M. Conway Department of Psychology Central Connecticut State University The goals of this study were (a) to identify managerial performance development constructs through factor analysis, (b) to understand their motivational determinants using personality correlates, and (c) to examine differences between rating sources. Factor analyses identified 5 developmental constructs: Interpersonal Effectiveness, Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations, Teamwork and Personal Adjustment, Adaptability, and Leadership and Development. Comparisons with Borman and Brush’s (1993) managerial performance megadimensions showed that the developmental constructs overlapped with but also added to the day-to-day performance domain. Each of the five factors showed a distinct pattern of personality correlates. Personality correlates supported hypotheses based on socioanalytic theory regarding the motive to get along with others (e.g., Interpersonal Effectiveness correlated with empathy and agreeableness) versus the motive to get ahead (e.g., Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations correlated with potency measures). Rating sources (supervisor, peer, subordinate, and self) showed some differences in their results. Several published works have addressed the constructs that make up the managerial job performance domain (e.g., Borman & Brush, 1993; McCauley, Lombardo, & Usher, 1989; Tornow & Pinto, 1976). These studies have tended to focus on job analysis-type data to identify the behaviors and activities managers engage in. Borman and Brush’s work in this area is probably the most comprehensive because they summarized and analyzed performance dimensions generated from critical incidents and task statements in a wide sample of organizations. They developed a set of 18 managerial “megadimensions” such as Training, Coaching, and Developing Subordinates. Requests for reprints should be sent to James M. Conway, Department of Psychology, Central Connecticut State University, New Britain, CT 06050–4010. 24 CONWAY RESEARCH ON HOW MANAGERS DEVELOP McCauley et al. (1989) suggested that focusing specifically on how managers develop provides a different perspective as compared to focusing on what managers do (Borman & Brush’s, 1993, focus). This perspective is potentially useful for two reasons: (a) it is particularly relevant to personal development interventions such as multisource feedback and (b) it can potentially identify important constructs missed by analyses of managers’ behaviors and activities. This study used an instrument called Benchmarks (McCauley et al., 1989), specifically developed based on a critical incidents analysis of developmental experiences. Benchmarks is based on a series of studies described by Lindsey, Homes, and McCall (1987) and McCall, Lombardo, and Morrison (1988). In these studies executives were asked to describe several “key events” (i.e., critical incidents) in their careers—events that made a difference in their managerial approaches. The executives were also asked to describe the lessons they learned from each event. This research effort was based on incidents from a wide variety of organizations. McCauley et al. (1989) described how the data were used to form the “Skills and Perspectives” section (the largest section) of Benchmarks. There are 16 Skills and Perspectives dimensions, listed and defined in Table 1 (Center for Creative Leadership, 1995; McCauley et al., 1989). McCauley et al. noted that Benchmarks includes dimensions not found in other performance feedback instruments, such as Straightforwardness and Composure, and Acting With Flexibility (balancing opposite qualities—e.g., being both tough and compassionate), which is an interpersonal skill. The Benchmarks dimensions have good validity; McCauley et al. reported that supervisor ratings on Benchmarks for several organizations were significantly related to a variety of criteria, including a measure of organizational advancement 24 to 30 months after Benchmarks was administered. With regard to higher order developmental constructs underlying Benchmarks, McCauley et al. (1989) identified three using a post hoc conceptual analysis: Respect for Self and Others, Adaptability, and Molding a Team. Respect for Self and Others included learning to show compassion, to be straightforward, and to put people at ease. McCauley et al. argued that Self-Awareness and Balance Between Personal Life and Work belong in this category too because an appreciation of the self is important for dealing well with others. Adaptability is referred to in current Benchmarks literature as “Meeting Job Challenges.” Meeting Job Challenges included developing resourcefulness, decisiveness, the drive to do what it takes to accomplish goals, and the ability to learn quickly. Finally, Molding a Team, referred to in current literature as “Leading People,” included learning to identify, recruit, and hire talented staff; to set a developmental climate; to confront problem subordinates; and other team-related behaviors. McCauley et al. argued that Leading People depends to some extent on the skills and perspectives inherent in the other two constructs but also adds unique team-oriented components. MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 25 TABLE 1 Benchmarks Skills and Perspective Dimensions 1. Resourcefulness (17 items): Can adapt to changing and often ambiguous circumstances, think strategically, make good decisions under pressure, set up complex work systems, engage in flexible problem-solving behavior, and work effectively with higher management. 2. Doing Whatever it Takes (14 items): Has perseverance and focus in the face of obstacles, e.g., taking charge, facing difficult situations with guts and tenacity. 3. Being a Quick Study (4 items): Quickly masters new technical and business knowledge. 4. Decisiveness (4 items): Prefers quick and approximate actions to slow and precise ones in many management situations. 5. Leading Employees (13 items): Delegates to employees effectively, broadens their opportunities, and acts with fairness toward them. 6. Setting a Developmental Climate (5 items): Provides a challenging climate to encourage employees’ development. 7. Confronting Problem Employees (4 items): Acts decisively and with fairness when dealing with problem employees. 8. Work Team Orientation (4 items): Accomplishes tasks through managing others. 9. Hiring Talented Staff (3 items): Hires talented people for his or her team. 10. Building and Mending Relationships (11 items): Knows how to build and maintain working relationships with coworkers and external parties (e.g., finding common ground, negotiating, understanding others, and getting cooperation in non-authority relationships). 11. Compassion and Sensitivity (4 items): Shows genuine interest in others and sensitivity to employees’ needs. 12. Straightforwardness and Composure (6 items): Is honorable and steadfast (e.g., relies on fact-based positions and doesn’t blame others for mistakes). 13. Balance Between Personal Life and Work (4 items): Balances work priorities with personal life so that neither is neglected. 14. Self-Awareness (4 items): Has an accurate picture of strengths and weaknesses and is willing to improve. 15. Putting People at Ease (4 items): Displays warmth and a good sense of humor. 16. Acting With Flexibility (5 items): Can behave in ways that are often seen as opposites (e.g., being both tough and compassionate). Note. This table is based on Center for Creative Leadership (1995) and McCauley, Lombardo, & Usher (1989). GOALS AND HYPOTHESES Identifying Developmental Performance Constructs My first goal in this study was to use factor analysis to determine whether McCauley et al.’s (1989) three constructs optimally describe the performance development domain. A related goal was to examine how consistent the constructs were across ratings by managers’ supervisors, peers, subordinates, and the managers themselves. Meta-analytic evidence on between-source correlations finds supervisor and peer ratings to be similar (Conway & Huffcutt, 1997; Harris & 26 CONWAY Schaubroeck, 1988). However, these two meta-analyses showed that self-ratings were not highly related to ratings by other sources, and Conway and Huffcutt (1997) provided the same type of evidence for subordinate ratings. One study directly compared factor structures across sources, finding no difference for peers and subordinates (Maurer, Raju, & Collins, 1998). Maurer et al. used a rating instrument containing only a single factor, team-building, and unlike this study did not include supervisor or self-ratings. Understanding Motivational Determinants by Examining Personality Correlates The second goal of this study was to evaluate the motivational determinants of performance development constructs using correlations with personality constructs. Recent research has shown that there are clear patterns of performance–personality relations, and that these relationships can help understand the motivational basis of performance constructs (Hogan, 1998; Hogan, Rybicki, Motowidlo, & Borman, 1998). The personality measures used in this study were the California Psychological Inventory (CPI; Gough, 1987) and the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers & McCaulley, 1985). A promising theoretical framework for understanding performance development constructs is the socioanalytic approach to personality (Hogan & Shelton, 1998). According to socioanalytic theory, two primary motives driving behavior are the desire to “get along” and the desire to “get ahead.” Getting along means feeling liked and supported, whereas getting ahead means gaining power and control of resources (Hogan & Shelton, 1998). Interactions in work settings can be seen as attempts to achieve one or both of these goals (Hogan et al., 1998; Hogan & Shelton, 1998). Hogan and Shelton noted that some people are more motivated to get along, whereas others are more motivated to get ahead and therefore different people use different behavioral strategies. The first performance development construct is Respect for Self and Others. This highly interpersonal construct (including, e.g., Compassion and Sensitivity) should be influenced by characteristics important for getting along. Therefore, Respect for Self and Others should be positively correlated with CPI Empathy (a social skill that should increase the ability to get along; Hogan, 1991) and MBTI Thinking–Feeling (interpreted by McCrae & Costa, 1989, as a measure of agreeableness). McCauley et al. (1989) linked knowledge of self to mental health, which is conceptually related to adjustment. Respect for Self and Others should therefore be related to CPI Self-Control (Gough, 1987, provides evidence showing that this dimension is correlated with measures of emotional stability). The second performance development construct was Meeting Job Challenges. This construct includes resourcefulness, decisiveness, the ability to learn quickly, MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 27 and the drive and attitudes to do these things. Taking charge, overcoming obstacles, and being decisive should be related to the characteristics necessary to get ahead rather than those necessary to get along. In a management situation one characteristic that is probably important for getting ahead is potency. According to Hough (1992), “Potency is defined as the degree of impact, influence, and energy that one displays” (p. 144). Meeting Job Challenges should therefore correlate positively with CPI Dominance. The third performance development construct was Leading People, including hiring, developing, and motivating subordinates. McCauley et al. (1989) suggested that Leading People depends partly on the first two constructs, Respect for Self and Others and Meeting Job Challenges. Therefore, a manager’s standing on Leading People reflects the characteristics necessary to get along and those necessary to get ahead. This balancing act should be predicted by “getting-along” dimensions such as CPI Empathy and “getting-ahead” dimensions such as CPI Dominance. Finally, differences between rating sources with respect to personality correlates were examined. These analyses were exploratory and there were no particular hypotheses. METHOD Participants A total of 2,110 managers from a variety of industries and management levels participated in a leadership development seminar. Each manager was rated on Benchmarks by at least one supervisor, one peer, and one subordinate as well as by himself or herself. Ratings were not used for any administrative decisions. Of the 2,110 managers, 1,830 completed the CPI and 1,567 completed the MBTI. The CPI and MBTI were not used administratively. Because my goal was to factor analyze each source’s ratings and make comparisons across sources, I included only one member of each source (when there were multiple members from a source I randomly chose one member). Demographic data showed that participants represented many organizational types (e.g., manufacturing, finance, public sector, nonprofit; 88% were from private for-profit organizations), functional areas (e.g., accounting, marketing), and levels of management. Most managers were White (94%), male (70%), and had at least a Bachelors degree (89%). The mean age was 42 years. Instruments Benchmarks. The Benchmarks Skills and Perspectives section contains 106 items (statements such as “has personal warmth”) forming 16 dimensions as de- 28 CONWAY scribed in Table 1. The development of Benchmarks was described in detail by McCauley et al. (1989), who reported coefficient alphas for supervisor ratings of .75 or higher for each of the 16 dimensions. McCauley et al. also reported significant validity coefficients for predicting organizational advancement. CPI. CPI Form 462 (Gough, 1987) includes 462 true–false items measuring 20 “folk constructs” (concepts people use in everyday language to describe themselves and others). Gough reported coefficient alphas for the CPI scales ranging from .52 to .79. Only 19 of the CPI constructs were used in this study (data for Femininity/Masculinity were not available). MBTI. The MBTI Form F (Myers & McCaulley, 1985) consists of 166 items, of which 95 are scored. Although the MBTI is intended to measure personality types, McCrae and Costa (1989) presented evidence that the MBTI measures continuous dimensions. Eight unipolar dimensions form four pairs (e.g., Extraversion and Introversion), and the two unipolar dimensions in each pair are almost completely ipsative (McCrae & Costa, 1989). In this study I used four bipolar dimensions, each based on a combination of a pair of unipolar dimensions. McCrae and Costa suggested that these four bipolar dimensions represent four of the Big Five personality factors: MBTI Extraversion–Introversion (EI) measures extraversion, MBTI Sensing–Intuition (SN) measures openness to experience, MBTI Thinking–Feeling (TF) measures agreeableness, and MBTI Judging–Perceiving (JP) measures conscientiousness. Myers and McCaulley reported coefficient alphas ranging from .76 to .83. Overview of Analyses In this study I used a combination of exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to identify higher order constructs underlying Benchmarks. CFA is appropriate when a strong theory exists about the common factor structure. Although McCauley et al. (1989) speculated on the higher order constructs of Benchmarks, this is not strong enough to justify CFA. CFA also usually requires allowing a variable to load only on its hypothesized factor (Hurley et al., 1997), even though a variable might load on multiple factors including unhypothesized ones. EFA, on the other hand, is well-suited to identifying multiple loadings. I began with an EFA of the 16 supervisor-rated Benchmarks scales. I used the resulting parameter estimates to derive a hypothesized model for the other three sources. This hypothesized model was fit to each of the other sources’ ratings using CFA. These CFAs tested whether the factor structures of peer, subordinate, and self-ratings were the same as that for supervisor ratings. Supervisors were used as the “standard” because their ratings represent the most common and best ac- MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 29 cepted way to measure work performance (Murphy & Cleveland, 1995), and because two meta-analyses have shown supervisor ratings to be more reliable than peer ratings (Conway & Huffcutt, 1997; Viswesvaran, Ones, & Schmidt, 1996) or subordinate ratings (Conway & Huffcutt, 1997). Finally, factor scores based on the factor analyses were correlated with CPI and MBTI dimensions. RESULTS Factor Analyses EFA for supervisor ratings. Supervisor ratings on the 16 Benchmarks Skills and Perspectives scales (means, standard deviations, and correlations appear in Table 2) were subjected to a maximum likelihood EFA using squared multiple correlations as prior communality estimates. Ford, MacCallum, and Tait (1986) and MacCallum (1998) advocated this type of common factor analysis over techniques such as principal components analysis. SAS Proc Factor software (Version 6; SAS Institute, 1989) was used and a Promax oblique rotation was conducted. Criteria for number of factors included the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1992), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), freedom from improper estimates (communalities greater than 1, which can occur with maximum likelihood estimation), and the interpretability of the solution. A TLI of at least .90 is usually taken to indicate acceptable fit. Browne and Cudeck suggested that RMSEA values less than .05 indicate a close fit between the model and the data, and RMSEA values less than .08 indicate reasonable fit. MacCallum (1998) further recommended examining confidence intervals for RMSEA to assess the fit statistic’s accuracy. Due to the large sample size in this study all 90% confidence intervals were small, approximately .01 in width, and the intervals will not be reported further later. The number of factors was determined by examining solutions with numbers of factors ranging from one to six. The six-factor solution contained an estimated communality greater than one, which can indicate poorly defined factors (e.g., only a single variable loading on a factor; McDonald, 1985). One- and two-factor solutions showed large RMSEA values of .160 and .116, respectively, and low TLI values of .71 and .85, respectively, necessitating the rejection of these models. The three-factor model showed a large RMSEA of .092 and a barely acceptable TLI of .90, indicating this model should also be rejected. It is worth noting, however, that the factor structure for this model was very consistent with McCauley et al.’s (1989) hypothesized constructs. Four- and five-factor solutions had reasonable RMSEA values (i.e., less than .08) of .072 and .065, respectively, and relatively high TLI values of .94 and .95, respectively. The five-factor solution had the lower RMSEA value, the higher TLI value, and the more interpretable pattern of loadings (standardized regression co- .53 .54 .62 .77 .57 .57 .71 .73 .64 .65 .61 .61 .75 .70 .77 .62 3.66 3.82 4.05 3.64 3.59 3.77 3.39 3.60 3.70 3.63 3.75 4.14 3.85 3.62 3.90 3.64 1. Resourcefulness 2. Doing Whatever it Takes 3. Being a Quick Study 4. Decisiveness 5. Leading Employees 6. Setting a Developmental Climate 7. Confronting Problem Employees 8. Work Team Orientation 9. Hiring Talented Staff 10. Building/Mending Relationships 11. Compassion and Sensitivity 12. Straightforwardness /Composure 13. Balance: Personal Life and Work 14. Self-Awareness 15. Putting People at Ease 16. Acting With Flexibility SD M Dimension .69 .59 .36 .15 .45 .42 .52 .68 .38 .53 .64 .46 .67 .65 1.00 .78 1 .63 .51 .33 .06 .33 .35 .53 .51 .29 .56 .59 .65 .58 .66 1.00 2 .36 .32 .12 .09 .24 .16 .34 .32 .12 .31 1.00 .39 .35 .39 3 .31 .22 .11 .03 .08 .08 .31 .17 .14 .46 1.00 .25 .38 4 .76 .61 .52 .25 .47 .66 .55 .72 .63 .51 1.00 .80 5 .69 .53 .45 .15 .37 .59 .58 .59 .49 .49 1.00 6 .49 .37 .16 .11 .25 .27 .48 .35 .34 1.00 7 .47 .36 .32 .32 .30 .40 .41 .43 1.00 8 .48 .38 .28 .14 .25 .37 1.00 .39 9 .76 .65 .66 .21 .51 .61 1.00 10 TABLE 2 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Supervisor Ratings .61 .51 .61 .27 .35 1.00 11 .48 .48 .30 .26 1.00 12 .24 .19 .23 1.00 13 .66 1.00 .46 14 .57 1.00 15 1.00 16 MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 31 efficients). I therefore accepted the five-factor solution, and the loadings and uniquenesses (a uniqueness was calculated as 1 minus the communality) are shown in Table 3. Factor correlations are shown in Table 4. The fact that the RMSEA value was above .05 indicates that the model did not fit extremely well. However, the poor results for the six-factor model suggest that five factors is the most reasonable solution for these data. CFA for peer, subordinate, and self-ratings. Next I applied the supervisor parameter estimates shown in Tables 3 and 4 to peer, subordinate, and self-ratings using CFA. Using LISREL 8 I fixed all model parameters at the supervisor values, and then separately assessed the fit of this model to each source’s data. This represents the strongest possible form of CFA, in which no parameters are estimated (Hurley et al., 1997). Peer and subordinate ratings showed acceptable levels of fit with RMSEA values of .055 and .074, respectively, and TLI values of .97 and .95, respectively. Self-ratings showed poor fit with a RMSEA of .086 and a TLI of .88. I next estimated a less restricted model, in which the loadings and uniquenesses were fixed but factor correlations were estimated. If a source showed better fit for this model than for one with fixed factor correlations, then the factor correlations for that source’s ratings differed from those for the supervisors’ ratings. Widaman (1985) suggested that an increase in the TLI of .01 showed a better fit; no particular standard for change in RMSEA is available. Peers showed virtually no change in fit, indicating that the factor structure of supervisor correlations is reasonable for peers as well. Subordinates did show better fit for the model with estimated factor correlations, with a RMSEA of .065 (decrease of almost .01) and a TLI of .96 (increase of .01). Examination of the factor correlation estimates showed that they were significantly higher than the supervisor values. Supervisor factor correlations in Table 4 averaged .50, whereas the subordinate factor correlations averaged .68, suggesting that the subordinates did not distinguish as well between the different rating factors, resulting in the higher factor correlations. Finally, self-ratings showed no improvement in fit when factor correlations were estimated. The supervisor model is a poor fit for the self-ratings. EFA for self-ratings. Due to the poorly fitting CFA model, I conducted EFAs of the self-ratings. Results were surprisingly similar to those for supervisors. A five-factor solution was found to be the best, and the pattern of loadings looked quite similar to the supervisor loadings. The major differences appeared to be that most self-loadings and self-factor correlations were lower than the corresponding supervisor values. Interpretation of the five-factor solution. The loadings in Table 3 show an interpretable pattern. Factor labels and definitions appear in Table 5. The first factor is clearly an Interpersonal Effectiveness factor and corresponds reasonably well Note. .05 .14 –.16 .01 .17 .15 –.10 –.03 –.03 .64 .59 .20 .12 .40 .94 .47 Interpersonal All loadings greater than .30 are italicized. 1. Resourcefulness 2. Doing Whatever it Takes 3. Being a Quick Study 4. Decisiveness 5. Leading Employees 6. Setting a Developmental Climate 7. Confronting Problem Employees 8. Work Team Orientation 9. Hiring Talented Staff 10. Building/Mending Relationships 11. Compassion and Sensitivity 12. Straightforwardness/Composure 13. Balance: Personal Life and Work 14. Self-Awareness 15. Putting People at Ease 16. Acting With Flexibility Dimension .15 .59 .08 .84 –.03 .12 .56 .02 .24 –.07 –.10 –.08 –.02 .09 .05 .18 Willingness .10 –.13 –.19 –.08 .35 –.01 .39 .59 .17 .21 .04 .32 .35 .22 –.08 .24 Teamwork/Personal Adjustment Factor Loadings .75 .35 .80 –.03 .12 .12 –.06 –.15 .09 .29 –.10 .28 –.10 .21 –.19 .12 Adaptability TABLE 3 Factor Loadings and Uniquenesses for Supervisor Benchmarks Ratings .02 .11 .07 –.06 .50 .67 .06 .31 .34 –.07 .38 –.08 –.03 –.03 .02 .10 Leadership .12 .13 .45 .39 .11 .18 .47 .48 .57 .17 .38 .65 .87 .46 .32 .24 Uniquenesses 32 CONWAY MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 33 TABLE 4 Factor Correlations for Supervisor Benchmarks Ratings Factor 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Interpersonal Willingness Teamwork/personal adjustment Adaptability Leadership 1 2 3 4 5 1.00 .29 .59 .56 .54 1.00 .29 .62 .50 1.00 .54 .57 1.00 .52 1.00 to McCauley et al.’s (1989) Respect for Self and Others. This factor appears to reflect the desire to get along, and was defined by Putting People at Ease with a loading of .94. Other high-loading scales (loadings in parentheses) were Building and Mending Relationships (.64), Compassion and Sensitivity (.59), Acting With Flexibility (.47; e.g., “is tough and at the same time compassionate”), and Self-Awareness (.40; e.g., “does an honest self-assessment”). Scales with slightly negative loadings were Being a Quick Study (–.16) and Confronting Problem Employees (–.10). The Interpersonal Effectiveness factor appears to tap effectiveness at getting along and making others feel comfortable and supported, with some focus on using this behavior to achieve business goals (e.g., Building and Mending Relationships; see the definition in Table 1). The small negative loading for Confronting Problem Employees indicates that the interpersonal skill measured by this factor does not extend to difficult situations, however. The self-oriented scales tended not to load on this factor; the exception was Self-Awareness. McCauley et al. (1989) suggested that Straightforwardness and Composure and Balance Between Personal Life and Work would also be a part of this construct, but they were not. The main focus of the factor is on relationships with others, with only a small focus on the self. The second factor taps a Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations. The Willingness factor represents the volitional part of McCauley et al.’s (1989) Meeting Job Challenges, the part dealing with the drive and attitudes needed to cope with job demands (the other part of McCauley et al.’s construct was represented by this study’s fourth factor). This behavior should be driven by a desire to get ahead. Decisiveness had the highest loading at .84. This scale taps a willingness to make decisions without hesitating. Doing Whatever it Takes (loading of .59) includes perseverance, showing tenacity in difficult situations, taking responsibility, and seizing opportunities. Confronting Problem Employees (loading of .56) includes, for example, being quick to confront people presenting problems, and being decisive with tough decisions such as layoffs. This factor taps the willingness to make difficult decisions and confront difficult situations without procrastination. The third factor represents a sense of Teamwork and Personal Adjustment. The highest loading scale was Work-Team Orientation (.59). The items comprising 34 CONWAY TABLE 5 Factor Labels, Definitions, and Corresponding Borman and Brush (1993) Megadimensions Factor 1: Interpersonal Effectiveness. Showing good social skill (e.g., tact, compassion, flexibility), making others feel comfortable, and influencing others. Borman and Brush Megadimensions (numbers are from Borman and Brush’s numbering system) 8. Maintaining good working relationships 17. Selling/influencing Factor 2: Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations. Showing courage and perseverance, and having the confidence and willingness to make decisions, confront problem employees, take charge, and do whatever else is necessary in challenging situations. Borman and Brush Megadimensions 12. Persisting to reach goals 13. Handling crises and stress Factor 3: Teamwork and Personal Adjustment. Having an orientation toward working through the team, and being well-adjusted (e.g., not obsessed with work; honest and not cynical or moody). Borman and Brush Megadimensions 9. Coordinating subordinates and other resources to get the job done Factor 4: Adaptability. Showing the ability to learn quickly and apply learning to think strategically, work with executives, make good decisions, and solve problems. Borman and Brush Megadimensions 1. Planning and organizing 6. Technical proficiency 10. Decision making/problem solving 15. Monitoring and controlling resources 18. Collecting and interpreting data Factor 5: Leadership and Development. Hiring competent people and effectively providing them with the opportunity and motivation to develop skills (e.g., delegating, giving decision-making responsibility to subordinates). Borman and Brush Megadimensions 2. Guiding, directing, and motivating subordinates and providing feedback 3. Training, coaching, and developing subordinates 11. Staffing 16. Delegating Borman and Brush Megadimensions Not Corresponding to Benchmarks Factors 4. Communicating effectively and keeping others informed 5. Representing the organization to customers and the public 7. Administration and paperwork 14. Organizational commitment this scale show that the focus is on the manager working through the team to accomplish goals rather than as an individual. Four scales had loadings ranging from .39 to .32: Confronting Problem Employees (.39), Leading Employees (.35), Balance Between Personal Life and Work (.35), and Straightforwardness and Composure (.32). Doing Whatever it Takes and Being a Quick Study had lower, negative loadings (–.13 and –.19, respectively). MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 35 High loadings for Work-Team Orientation and Leading Employees (e.g., delegating, providing opportunities for decision making) indicate a clear orientation toward the team. Confronting Problem Employees is also fairly consistent with this orientation. Doing Whatever it Takes and Being a Quick Study tend to focus on the manager as an individual, so the small negative loadings are understandable. The Balance and Straightforwardness scales that McCauley et al. (1989) associated with the Interpersonal Effectiveness factor loaded moderately highly on this factor instead. These scales seem to indicate personal adjustment. The Work-Team Orientation scale can also be interpreted in terms of adjustment. It probably takes a certain degree of self-control and perspective for a manager to allow a team to handle important tasks, rather than trying to do things himself or herself. So, better adjusted managers will probably find it easier to have a team orientation. The fourth factor represents half of McCauley et al.’s (1989) Meeting Job Challenges construct (the other half was represented by the second factor, Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations). The two scales with very high loadings were Being a Quick Study (.80) and Resourcefulness (.75). Doing Whatever it Takes had a loading of .35. Scales with small negative loadings were Work-Team Orientation (–.15) and Putting People at Ease (–.19). McCauley et al.’s original label of Adaptability seems appropriate here. The highest loading scales indicate that a manager scoring high on this factor is one who can assimilate new information quickly and use it to think strategically, work with executives, solve problems, and make good decisions. The small negative loadings indicate that Adaptability is an individually focused (rather than team- or other-focused) factor. Although the Willingness factor was clearly volitional, this study’s Adaptability factor was more oriented toward mental ability, an intellectual orientation, and creativity as well as the ability to withstand stress (e.g., making decisions under pressure, part of the Resourcefulness scale). The fifth factor is a Leadership and Development factor, similar to McCauley et al.’s (1989) Leading People factor. As noted in the Introduction, this factor probably requires both the desire to get along and the desire to get ahead. The highest loadings were for Setting a Developmental Climate (.67) and Leading Employees (.50), with moderately high loadings for Compassion and Sensitivity (.38), Hiring Talented Staff (.34), and Work-Team Orientation (.31). Although Factor 3 (Teamwork and Personal Adjustment) focuses more on the orientation to work through the team rather than as an individual, the Leadership and Development factor focuses more on selecting, challenging, developing, and motivating subordinates. One way to think of this distinction is in terms of the tendency to do something versus the effectiveness in doing it. Teamwork and Personal Adjustment is oriented toward the tendency to work through a team, and Leadership and Development is oriented toward the effectiveness at working through the team (e.g., motivating subordinates to take advantage of developmental opportunities and achieve goals). 36 CONWAY Personality Correlates I calculated factor scores using scoring coefficients from SAS (estimated by regression; Kim & Mueller, 1978), and then computed correlations between the factor scores and CPI and MBTI dimensions. This was done both with the sources kept separate and with the scores for each factor averaged across supervisors, peers, and subordinates. I excluded self-ratings for two reasons. First, self-ratings showed a different factor structure so the factor scores would not be comparable. Second, self-ratings showed considerably higher correlations with personality measures than did other sources’ ratings. This was probably because the personality measures were self-reports and the correlations were inflated by shared method variance. I corrected the correlations for unreliability in both the performance ratings and the personality dimensions to get estimates of correlations between constructs. For personality measures I used coefficient alphas reported in Gough (1987) and Myers and McCaulley (1985). For performance factors I used interrater reliabilities. To correct the scores aggregated across sources I used coefficient alphas for each factor, computed by treating each source as an item. The resulting reliabilities ranged from .59 (Interpersonal Effectiveness) to .44 (Leadership and Development). To correct each individual source’s correlations the appropriate reliability would take into account consistency across ratings by members of the same source. To calculate these reliabilities I used a somewhat larger database (N = 2,809 managers) of which the current data were a subset. In the larger dataset many managers had multiple raters for at least one source; using all these raters I computed intraclass correlations (ICCs) separately by source for each factor. Supervisors had the highest ICCs, all above .40 except Leadership and Development (ICC = .30). Peer and subordinate ICCs were generally in the .30s. For both sources Leadership and Development had the lowest ICC (.25 for both sources). Personality correlates of factor scores aggregated across sources. For rating factors aggregated across sources, uncorrected and corrected correlations are shown in Table 6. Corrected correlations with absolute values of at least .15 are italicized in Table 6. The Interpersonal Effectiveness factor, representing the motive to get along, correlated most strongly with CPI Empathy and Tolerance, and MBTI Thinking–Feeling (agreeableness; McCrae & Costa, 1989). These correlations were consistent with hypotheses for the “getting along” construct. This factor also correlated with CPI Socialization and Self-Control, classified by Kamp and Hough (1988) as measures of adjustment. The Willingness factor, representing the motive to get ahead, correlated most strongly with CPI Dominance, Independence, Self-acceptance, and Social Presence. These dimensions were classified by Kamp and Hough (1988) as measures of potency. Potency measures were hypothesized to reflect the “getting ahead” MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 37 TABLE 6 Personality Correlates of Rating Factor Scores Aggregated Across Sources Performance Development Factor Dimension CPI Dominance Capacity for Status Sociability Social Presence Self-Acceptance Independence Empathy Responsibility Socialization Self-Control Good Impression Communality Well-Being Tolerance Achievement via Conformance Achievement via Independence Intellectual Efficiency Psychological-mindedness Flexibility MBTI Extraversion–Introversion Sensing–Intuition Thinking–Feeling Judging–Perceiving Interpersonal Willingness Teamwork/ Adjustment Adaptability Leadership –.02 (–.04) .06 (.10) .08 (.12) .05 (.08) .05 (.10) –.07 (–.10) .15 (.26) .07 (.11) .12 (.18) .10 (.15) .07 (.10) .02 (.03) .05 (.07) .11 (.17) .02 (.04) .23 (.34) .08 (.14) .09 (.14) .14 (.22) .16 (.29) .19 (.30) .05 (.09) .03 (.04) –.05 (–.08) –.10 (–.15) –.02 (–.03) –.05 (–.08) .06 (.09) .01 (.01) .00 (–.01) –.03 (–.05) –.01 (–.01) –.01 (–.02) .00 (.00) –.02 (–.03) –.04 (–.06) .06 (.10) .06 (.09) .14 (.22) .14 (.22) .07 (.11) .03 (.05) .09 (.14) .10 (.16) .07 (.10) .05 (.09) .05 (.10) .01 (.01) .04 (.06) .04 (.08) .06 (.10) .05 (.09) .12 (.21) .08 (.14) .09 (.15) .06 (.09) .00 (.00) .09 (.15) .13 (.23) .07 (.12) .07 (.12) .06 (.12) .07 (.13) .07 (.14) .08 (.17) .05 (.08) .12 (.23) .05 (.10) .07 (.12) .04 (.07) .03 (.06) –.01 (–.02) .06 (.11) .08 (.14) .02 (.04) .07 (.10) .01 (.01) .08 (.13) .12 (.22) .09 (.15) .03 (.04) .01 (.02) .08 (.12) .04 (.06) .01 (.01) .01 (.01) .08 (.12) .02 (.03) .00 (.00) .12 (.20) .10 (.17) .05 (.08) .06 (.11) .05 (.10) .05 (.10) –.07 (–.09) .03 (.04) .20 (.30) .09 (.13) –.11 (–.17) .10 (.15) –.07 (–.11) .06 (.08) .03 (.04) –.02 (–.03) .09 (.13) –.03 (–.04) .03 (.05) .09 (.15) –.02 (–.04) .02 (.04) –.06 (–.10) .11 (.18) .10 (.17) .04 (.07) Note. Values in parentheses are correlations corrected for unreliability in both performance development and personality constructs. Corrected correlations of at least .15 are italicized. construct, and these results support that hypothesis. There were negative correlations with MBTI Extraversion–Introversion (indicating more extraverted behavior associated with higher factor scores) and CPI Self-Control (indicating better adjusted managers performed more poorly on this dimension). Teamwork and Personal Adjustment correlated most highly and positively with adjustment-oriented personality constructs including CPI Socialization and Self-Control. These results are consistent with Howard and Bray’s (1988) finding that managers’ adjustment correlated negatively with impulsivity. The Teamwork factor also correlated with CPI Tolerance. 38 CONWAY Adaptability correlated with personality constructs indicating an intellectual, creative orientation such as CPI Intellectual Efficiency and Achievement via Independence (according to Gough, 1987, both of these constructs were associated with adjective checklist ratings such as intelligent, insightful, and clear-thinking), and MBTI Sensing–Intuition (this dimension was interpreted by McCrae & Costa, 1989, as a measure of openness to experience). This factor also correlated with dependability and adjustment-oriented constructs such as CPI Responsibility, Self-Control, Well-being, and Tolerance. Leadership and Development, as expected, correlated with personality constructs representing both the motive to get along (CPI Empathy and MBTI Thinking–Feeling) and the motive to get ahead (CPI Self-Acceptance, a measure of potency). The predicted correlations with potency constructs were more strongly confirmed for supervisor ratings and peer ratings separately, without subordinate ratings (e.g., CPI Sociability and Social Presence in addition to Self-Acceptance correlated with supervisors and peers; see Table 7). Personality correlates by source. Table 7 shows factor score–personality correlations (corrected for unreliability) separately for supervisors, peers, and subTABLE 7 Personality Correlates of Rating Factor Scores By Source (Correlations All Corrected for Unreliability) Source Factor Interpersonal Effectiveness CPI Empathy CPI Socialization CPI Self-Control CPI Tolerance MBTI Thinking-Feeling MBTI Judging-Perceiving Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations CPI Dominance CPI Capacity for Status CPI Sociability CPI Social Presence CPI Self-Acceptance CPI Independence CPI Self-Control MBTI Extraversion-Introversion MBTI Sensing-Intuition Supervisor Peer Subordinate .26 .21 .16 .21 .31 .15 .27 .15 .10 .13 .27 .14 .18 .13 .14 .13 .23 .06 .31 .13 .16 .23 .31 .29 –.16 –.18 .15 .33 .16 .18 .25 .34 .29 –.17 –.18 .11 .28 .08 .06 .13 .13 .22 –.08 –.10 .15 (Continued) MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 39 TABLE 7 (Continued) Source Factor Teamwork and Personal Adjustment CPI Empathy CPI Socialization CPI Self-Control CPI Well-Being CPI Tolerance Adaptability CPI Responsibility CPI Socialization CPI Self-Control CPI Well-Being CPI Tolerance CPI Achievement via Independence CPI Intellectual Efficiency CPI Psychological-Mindedness MBTI Sensing-Intuition Leadership and Development CPI Capacity for Status CPI Sociability CPI Social Presence CPI Self-Acceptance CPI Independence CPI Empathy CPI Socialization CPI Well-Being CPI Tolerance CPI Achievement via Independence CPI Intellectual Efficiency MBTI Sensing-Intuition MBTI Thinking-Feeling Supervisor Peer Subordinate .06 .25 .24 .18 .21 .17 .17 .15 .07 .11 .05 .17 .19 .12 .10 .20 .18 .16 .17 .26 .20 .16 .18 .15 .18 .06 .10 .09 .17 .17 .17 .12 .08 .15 .12 .13 .11 .16 .18 .17 .14 .15 .17 .15 .16 .24 .16 .24 .16 .18 .20 .20 .15 .19 .16 .10 .16 .17 .25 .11 .27 .06 .03 .12 .11 .07 .18 .17 .05 .05 .05 –.01 –.02 .13 .10 .08 .08 .11 .08 .13 .12 ordinates. Only personality constructs showing a corrected correlation of at least .15 with at least one source are shown. The personality constructs correlating with each factor tended to be the same across sources. However, supervisors usually showed the highest correlations and subordinates usually showed the lowest. The low subordinate correlations were especially noticeable for the Leadership and Development factor. There were some exceptions to the generally higher supervisor–personality correlations. Corrected peer–personality correlations equaled supervisor correlations for the Willingness factor. And for each of the five factors, peers showed higher cor- 40 CONWAY rected correlations with CPI Empathy than did either of the other sources. This suggests that peers are particularly attuned to and affected by empathic behaviors. DISCUSSION This study adds to a growing literature on the nature of job performance constructs (e.g., Borman & Brush, 1993; Campbell, McCloy, Oppler, & Sager, 1993) and provides further evidence that when criterion constructs and personality constructs are carefully matched, a clear, interpretable pattern of relations emerges (Hogan, 1998; Hough, 1998). The performance constructs examined in this study particularly concerned the development of managerial performance, rather than performance activities contained in the normal workday (the concern of previous research; e.g., Borman & Brush, 1993). Factor analyses revealed five managerial performance development factors, and correlations with personality measures suggest underlying motivational determinants. Integration With Borman and Brush’s (1993) Managerial Performance Megadimensions The developmental perspective can augment and expand our understanding of the concept of managerial performance in general. To accomplish this it is important to examine how the constructs identified here fit in with previous literature. I will do this by interpreting Borman and Brush’s (1993) 18 managerial performance megadimensions in terms of this study’s five factors. Table 5 shows relations between the five performance development factors and Borman and Brush’s megadimensions. The Interpersonal Effectiveness factor overlaps with two of the megadimensions: “Maintaining good working relationships” and “Selling/influencing.” For both taxonomies the emphasis is on establishing smooth relationships allowing the manager to gain cooperation and achieve goals. The Willingness factor also overlaps with two megadimensions: “Persisting to reach goals” and “Handling crises and stress.” The “persisting” megadimension overlaps with the “perseverance” aspect of Doing Whatever it Takes. The “handling crises” megadimension emphasizes quickly dealing with unexpected situations and tight deadlines. This is similar to Decisiveness and also overlaps with Doing Whatever it Takes. This study’s Willingness factor has a unique focus on Confronting Problem Employees. The Teamwork factor has only a relatively weak link, to the “Coordinating subordinates and other resources to get the job done” megadimension. Working through a team implies this type of coordination. Teamwork included a substantial MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 41 adjustment component (e.g., Balance Between Personal Life and Work and Straightforwardness and Composure) that did not overlap with the megadimensions. The lack of overlap is probably due to the fact that adjustment per se is not an activity. However, the Management Progress Study results (Howard & Bray, 1988) suggested that, relative to poorly adjusted managers, better adjusted managers tended to experience positive changes over time. These changes included increased dominance, achievement motivation, and optimism. They also found a positive, but low, relation between adjustment and organizational advancement. The Adaptability factor shows some degree of overlap with five megadimensions, all of which have to do with acquiring and applying knowledge. The megadimensions are “Planning and organizing” (e.g., including “strategic planning; the Resourcefulness scale has a “thinking strategically” component), “Technical proficiency,” “Decision making/problem solving,” “Monitoring and controlling resources” (Resourcefulness includes items regarding building systems that are self-monitoring and can be managed by remote control), and “Collecting and interpreting data” (the “problem-solving” component of Resourcefulness includes gathering information and analyzing situations). Finally, the Leadership and Development factor overlaps with four megadimensions: “Guiding, directing, and motivating subordinates and providing feedback”; “Training, coaching, and developing subordinates”; “Staffing”; and “Delegating.” There were four megadimensions that did not fit into one of this study’s factors: “Communicating effectively and keeping others informed,” “Representing the organization to customers and the public,” “Administration and paperwork,” and “Organizational commitment.” McCauley et al. (1989) noted the lack of focus in Benchmarks on administrative and communication skills, and speculated that these skills are mastered early and are less important than other skills to managerial development. The “Representing” and “Organizational commitment” megadimensions are job-dedication-oriented behaviors that probably reflect a general tendency to be positive and conscientious. These tendencies are probably well established before one attains a managerial position so they do not represent common developmental experiences. Each of the five performance development factors identified in this study overlapped with at least one of Borman and Brush’s megadimensions. The Teamwork and Personal Adjustment factor had the smallest amount of overlap, with only one megadimension. This weak link suggests that the content of this factor is relatively specific to a developmental focus (especially the “Personal Adjustment” part of the factor). Some megadimensions did not overlap with any of this study’s factors, indicating areas more important for day-to-day activities than for performance development. 42 CONWAY One limitation of this discussion is that these results may be somewhat specific to the Benchmarks instrument. However, Benchmarks was carefully developed based on extensive collection of information from managers in many organizations. This broad sampling should tend to mitigate instrument-specific biases and promote generalizability. Why Personality is Related to Managers’ Behavior Personality correlates generally supported hypotheses. The Interpersonal Effectiveness factor correlated with CPI Empathy and MBTI Thinking–Feeling (interpreted here as agreeableness), providing evidence that this factor reveals the motive to get along with others. The Willingness factor correlated with several potency-related CPI dimensions, suggesting that this factor reveals the motive to get ahead. Interestingly, Willingness had a negative correlation with CPI Self-Control. The Leadership and Development factor correlated with empathy and agreeableness, and also showed some relations with potency variables. Leadership and Development therefore shows both the motive to get along and the motive to get ahead. The other two factors, Adaptability and Teamwork and Personal Adjustment, also showed distinct patterns of personality correlates. Why are responses to personality instruments related to others’ ratings of managers? Multisource performance ratings reflect managers’ behaviors (and corresponding developmental needs). Hogan and Shelton (1998) suggested that a person’s behaviors—what interactions a person enters into, and how the interactions are handled—are a function of identity, or the person’s hopes, dreams, fears, and self-image. According to this view, a person is motivated to engage in behaviors consistent with his or her identity but not behaviors that are inconsistent. For example, if I see myself as someone who is well-liked by others but who is not comfortable leading others and making difficult decisions, I will be motivated to engage in “getting along” behaviors such as showing empathy but I will not be motivated to engage in “getting ahead” behaviors such as taking charge. I might therefore be the kind of manager that Johnson, Schneider, and Oswald (1997) described as an “amiable underachiever,” scoring high on performance ratings for Interpersonal Effectiveness but low on performance ratings for Willingness to Handle Difficult Situations. Hogan and Shelton (1998) argued that responses to personality scales are another form of behavior that is governed by identity. The same identity that leads to amiable underachievement would also therefore lead to high scores on personality scales like empathy and low scores on scales like dominance. In other words, the personality–job performance relation exists because both personality inventory responses and job behavior reflect the same underlying identities and motives. MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 43 Practical Implications of Personality Correlates: Development and Selection Personality measures, given a motivational interpretation, reflect why a manager does things. Understanding a manger’s personality and motivations can be helpful in finding remedies for weaknesses. For example, the earlier section on personality–job performance relations suggests that amiable underachievers are typically motivated to get along but not to get ahead. However, Hogan and Shelton (1998) noted that others’ evaluations of our behavior depend on social skill in addition to motivation. It is possible that rather than lacking the motivation to get ahead, an amiable underachiever is motivated to get ahead as well as to get along, but lacks the social skills necessary for taking charge and for leading others. Such a manager would be one whose idealized self-image includes ambition and dominance, but whose attempts to lead forcefully are ineffective. The amiable underachiever’s problem could therefore be due to personality (lack of motivation to get ahead), or due to lack of skill. This distinction is important because, although personality is fairly stable, social skills are more easily trained (Hogan & Shelton, 1998). Personality measures used in conjunction with multisource feedback ratings can help to identify the source of a manager’s weakness. If the “amiably underachieving” manager scores low on personality scales indicating ambition and potency, then the source of the underachievement would appear to be personality-related. If, on the other hand, scores on these personality scales are high, the manager would probably like to be an achiever, but needs work on social skills to carry out getting-ahead behaviors effectively. Another example involves a manager receiving low ratings on Leadership and Development (shown to correlate with both getting along and getting ahead personality constructs). The low ratings might be because of a lack of motivation to get along, a lack of motivation to get ahead, or both. Scores on relevant personality constructs can help identify the underlying reason, leading to better targeted developmental experiences (e.g., improving interpersonal effectiveness vs. developing a more forceful motivational approach). Personality measures are also useful for managerial selection. If the personality measures are administered to managerial job candidates, the measures can be used to predict which candidates will need more or less developmental work in a particular area. For example, candidates scoring high on getting along personality dimensions such as empathy are likely to need less work in the Interpersonal Effectiveness area than low-scoring candidates. Selecting candidates who score high on relevant personality measures should reduce the need for extensive developmental work. 44 CONWAY Rating Source Differences Differences between rating sources were found both in factor analysis results and in personality correlates. Factor analysis parameter estimates were generally very similar. One exception was managers’ self-ratings. Self-loadings and self-factor correlations were lower than those for other sources. This result is consistent with meta-analyses showing self-ratings differed from those of other sources (Conway & Huffcutt, 1997; Harris & Schaubroeck, 1988) and adds to the literature showing that workers see their own performance quite differently than it is seen by others. Another exception to the consistent results across sources involved subordinates, who showed higher factor correlations than other sources. This finding suggests that subordinates did not distinguish between dimensions as well as supervisors and peers. Correlations with personality measures were generally strongest for supervisors and weakest for subordinates. The low subordinate correlations were especially evident for Leadership and Development. This is interesting because this dimension is very subordinate-focused and should be more important to subordinates than to other sources. Subordinate ratings are difficult to interpret based on these results. No personality scales correlated most highly with subordinates. It is possible that subordinate ratings depend more on situational factors than do supervisor or peer ratings. A number of leadership theories have proposed that the most appropriate type of leader behavior depends on the type of situation (e.g., Fielder & Garcia, 1987). Subordinates are probably better aware than supervisors or peers of the situation in which the manager’s behavior occurs, especially for Leadership and Development-related behavior. Subordinate ratings may better reflect the appropriateness of the manager’s behavior, given the situation. For example, peers and supervisors may rate based on the general tendency to provide challenging assignments to employees (a “getting ahead” behavior). Subordinates may be more sensitive to the appropriateness of the manager’s behavior, and rate not just based on the manager’s general tendency to try to get ahead, but based on how appropriate it is in the situation at hand. Future research should explore the extent to which differences in sources’ ratings reflect different, valid perspectives on performance as opposed to source-specific error variance. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This article was presented at the 1999 Annual Meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association. Thanks to the Center for Creative Leadership for providing the data for this project, and to Joyce Hogan, Margaret A. McManus, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this article. MANAGERIAL PERFORMANCE DEVELOPMENT 45 REFERENCES Borman, W. C., & Brush, D. H. (1993). More progress toward a taxonomy of managerial performance requirements. Human Performance, 6, 1–21. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21, 230–258. Campbell, J. P., McCloy, R. A., Oppler, S. H., & Sager, C. E. (1993). A theory of performance. In N. Schmitt & W. C. Borman (Eds.), Personnel selection in organizations (pp. 35–70). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Center for Creative Leadership. (1995). Benchmarks developmental learning guide. Greensboro, NC: Author. Conway, J. M., & Huffcutt, A. I. (1997). Psychometric properties of multi-source performance ratings: A meta-analysis of subordinate, supervisor, peer, and self-ratings. Human Performance, 10, 331–360. Fiedler, F. E., & Garcia, J. E. (1987). New approaches to effective leadership: Cognitive resources and organizational performance. New York: Wiley. Ford, J. K., MacCallum, R. C., & Tait, M. (1986). The application of exploratory factor analysis in applied psychology: A critical review and analysis. Personnel Psychology, 39, 291–314. Gough, H. G. (1987). CPI administrator’s guide. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Harris, M. M., & Schaubroeck, J. (1988). A meta-analysis of self–supervisor, self–peer, and peer–supervisor ratings. Personnel Psychology, 41, 43–62. Hogan, J. (1998). Introduction: Personality and job performance. Human Performance, 11, 125–127. Hogan, J., Rybicki, S. L., Motowidlo, S. J., & Borman, W. C. (1998). Relations between contextual performance, personality, and organizational advancement. Human Performance, 11, 189–207. Hogan, R. T. (1991). Personality and personality measurement. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 873–919). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Hogan, R., & Shelton, D. (1998). A socioanalytic perspective on job performance. Human Performance, 11, 129–144. Hough, L. M. (1992). The “Big Five” personality variables–construct confusion: Description versus prediction. Human Performance, 5, 139–155. Hough, L. M. (1998, April). Job performance models & personality taxonomies. In J. C. Hogan (Chair), Meaning and models of the personality–job performance relation. Symposium conducted at the 13th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Dallas, TX. Howard, A., & Bray, D. W. (1988). Managerial lives in transition: Advancing age and changing times. New York: Guilford. Hurley, A. E., Scandura, T. A., Schriesheim, C. A., Brannick, M. T., Seers, A., Vandenberg, R. J., & Williams, L. J. (1997). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Guidelines, issues, and alternatives. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 667–683. Johnson, J. W., Schneider, R. J., & Oswald, F. L. (1997). Toward a taxonomy of managerial performance profiles. Human Performance, 10, 227–250. Kamp, J. D., & Hough. L. M. (1988). Utility of temperament for predicting job performance. In L. M. Hough (Ed.), Utility of temperament, biodata, and interest assessment for predicting job performance (ARI Research Note 88–02; pp. 1–90). Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. Kim, J.-O., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis: Statistical methods and practical issues. Beverly Hills: Sage. Lindsey, E. H., Homes, V., & McCall, M. W., Jr. (1987). Key events in executives’ lives (Tech. Rep. No. 32). Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. 46 CONWAY MacCallum, R. (1998). Commentary on quantitative methods in I–O research. The Industrial–Organizational Psychologist, 35, 19–30. Maurer, T. J., Raju, N. S., & Collins, W. C. (1998). Peer and subordinate performance appraisal measurement equivalence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 693–702. McCall, M. W., Jr., Lombardo, M. M., & Morrison, A. M. (1988). The lessons of experience: How successful executives develop on the job. Lexington, MA: Lexington. McCauley, C. D., Lombardo, M. M., & Usher, C. J. (1989). Diagnosing management development needs: An instrument based on how managers develop. Journal of Management, 15, 389–403. McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1989). Reinterpreting the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 57, 17–40. McDonald, R. P. (1985). Factor analysis and related methods. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Murphy, K. R., & Cleveland, J. N. (1995). Understanding performance appraisal: Social, organizational, and goal-based perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. SAS Institute, Inc. (1989). SAS/STAT user’s guide, Version 6 (4th ed., Vol. 1). Cary, NC: Author. Tornow, W. W., & Pinto, P. R. (1976). The development of a managerial job taxonomy: A system for describing, classifying, and evaluating executive positions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 410–418. Viswesvaran, C., Ones, D. S., & Schmidt, F. L. (1996). Comparative analysis of the reliability of job performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 557–574. Widaman, K. F. (1985). Hierarchically nested covariance structure models for multitrait–multimethod data. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9, 1–26.