Improving the competitiveness of supply chains

advertisement

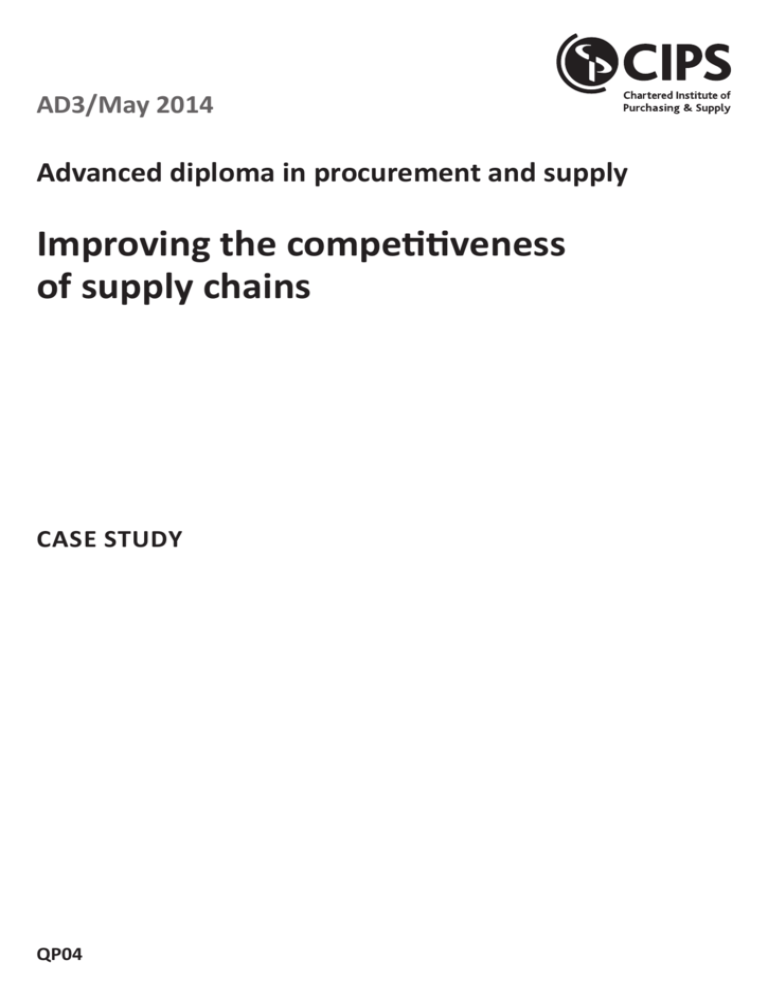

AD3/May 2014 Advanced diploma in procurement and supply Improving the competitiveness of supply chains CASE STUDY QP04 INSTRUCTIONS FOR CANDIDATES The pre-released case study examination is designed to assess your ability to apply the relevant theories, principles and techniques associated with the unit content to a realistic business situation. The examination is a three hour open-book examination. The examination questions will test each of the learning outcomes from the unit content. You will be expected to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of relevant theoretical principles, concepts and techniques; to apply these appropriately to the particular situation described in the case study and; above all, to make sound decisions. You will not gain marks by writing a general essay on the topic. Prepared notes may not be included as part of the answer. Please note that all work should be your own. Copying or plagiarism will not be tolerated and could result in no marks being awarded. If quotes or short extracts are used they should be attributed or the source of the information identified. You should acquaint yourself thoroughly with the case study before the examination. You must take your copy of the case study into the examination. Page 2 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 COMPETITIVENESS IN FASHION SUPPLY CHAINS Introduction Fashion, by definition, is transitory in nature – it does not linger for very long. In fact some fashions exist for very short periods and are rapidly superseded by other fashions. This is certainly true of the clothing and accessories markets, but can be equally true of other product categories. Fashion markets are not solely driven by what happens to be the current fashion trend. Seasonal factors are also significant. In countries where there is a significant Christian population or culture, Christmas has a major impact on sales demand across a large number of product categories. In fact categories such as jewellery depend on good Christmas trade for much of their annual profit. Weather also has a significant impact upon demand. A mild winter can result in lower than forecast sales of knitwear, heavy coats and other items designed to combat cold weather. Similarly, a cold or wet summer can result in lower demand for items such as t-shirts and beachwear. These seasonal, short-term changes in demand and styling, taken within the context of global supply networks, create volatile, complex and rapidly changing markets that pose substantial challenges to those seeking to exploit them. Martin Christopher et al (2004) determined that fashion markets would typically exhibit the following characteristics: • “Short life-cycles – the product is often ephemeral, designed to capture the mood of the moment: consequently, the period in which it will be saleable is likely to be very short and seasonal, measured in months or even weeks. • High volatility – demand for these products is rarely stable or linear. It may be influenced by the vagaries of weather, films, or even by pop stars and footballers. • Low predictability – because of the volatility of demand it is extremely difficult to forecast with any accuracy even total demand within a period, let alone week-by-week or item-by-item demand. • High impulse purchasing – many buying decisions by consumers for these products are made at the point of purchase. In other words, the shopper when confronted with the product is stimulated to buy it; hence the critical need for availability.” (Christopher M., Lowson R., Peck H., (2004) “Creating agile supply chains in the fashion industry”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 32 Iss: 8, pp.367 – 376 (5). Gordon Selfridge, founder of the famous Selfridges department store in London’s Oxford Street, was reputed to have said that retailing was all about ‘having the right product in the right place at the right time’. Having the right product involves a combination of the right style and colour, quality specification and price. Value for money is important and goods must also be fit for purpose, which includes compliance with any relevant legislation or regulations. Although by their nature the most fashionable products are not expected to have a long product life they must look good and meet quality standards. Fashion retailers at the more expensive end of the market may not regard price as a primary consideration in their marketing proposition. Within the mass market, however, it is essential to be price competitive. To achieve lower costs and compete effectively on price, so-called ‘fast fashion’ retailers source their finished goods globally and in large volumes from countries with the lowest production costs such as China, India and Bangladesh. Page 3 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 The most cost effective way of transporting finished goods from countries many thousands of miles away is by sea freight. However, this can take weeks and adds significantly to the order lead time for finished goods. Sea freight from China to Europe can take from four to six weeks. Air freight, which is much faster and can take days rather than weeks, is more costly and thus impedes price competitiveness. The challenge for the fast fashion retailers is to leverage the economies inherent in global sourcing of clothing and at the same time deal effectively with the longer timescales and distances involved, and their impact on flexibility of supply. This makes supply chain management complex as it involves controlling and managing large networks of distant suppliers, more effort in developing the product design function, and producing greater numbers of collections and individual designs (7). Andres Mazaira et al in their 2003 case analysis of Inditex-Zara (18) suggested that the following trends would be the determining factors for the future development of the global fast fashion sector: • • • • • • • • De-localisation of textile and clothing manufacture in Europe and North America. A strong increase in competitive pressure. Company growth strategy and forward-looking integration for clothing manufacturers. Development of distribution chains. Increased market participation for “killers”. Growing internationalisation. A strong commitment to flexibility. Low fidelity levels. ‘One-brand wardrobes’ no longer exist, and companies seek to increase their share in customer wardrobes” (19). Many of these predicted factors have now become reality. Many international fast fashion retailers such as Gap and Topshop source their products globally from independent producers. Often retailers claim to have long-standing relationships with their manufacturers and some express concern for the social and ethical governance of their supply chain. Retailers are concerned not just that product specification is met, but how the specification is met. Textile workers are traditionally among the lowest paid and most exploited in the world. Compliance with ethical and environmental codes can be as important as conformance to order specification. Managing these risks is a significant challenge for retailers. Basic and more predictable clothing such as T-shirts, for which it is easier to forecast demand further in advance and more accurately, is where retailers can best achieve economies of scale sourcing from low cost countries, particularly in Asia. One retailer in the UK sold 6 million T-shirts in 2006 (17). However, the profit margins on these types of products are lower than on the more innovative and more fashionable products where order volumes are lower and the lifecycle shorter. Fast fashion retailers, using supply networks of independently owned manufacturers, therefore try to predict and even influence demand for the more fashionable products. “Emerging fashion trends in each of these market groups would be very closely monitored as well as more general inspiration from movies, television, popular holiday destinations, music industry offerings and so on” (18). Different approaches to the management of global supply networks in the fast fashion marketplace are exhibited by three of the largest global fast fashion retailers: Benetton, H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) and Zara (Inditex Group). Page 4 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 Benetton Benetton is an Italian company and one of the first truly global fast fashion retailers, with more than 6,000 shops in 120 countries (Benetton Group 2013). While the whole of the European Union has become a net importer of clothing, Italy still has a positive balance of exports, although this dropped considerably between 1997 and 2007, falling from 50% to 17% with imports into Italy from China more than doubling in the same period (19). Benetton was founded in 1965 in Ponzano Veneto near Treviso, Italy and grew rapidly based on a business model that included quasi-franchised1 outlets (a minority of stores were wholly owned), a wholly owned manufacturing and dyeing facility, and a network of relationships with small to medium sized local manufacturers. These manufacturers included home workers that specialised in knitting, cutting and sewing. The suppliers operated in a tiered supply network with tier one suppliers coordinating tier two suppliers and tier two coordinating lower tiers, often consisting of the home workers. Benetton had also developed a new method for dyeing knitted cotton goods. This meant that it was possible to alter the colour balance of orders very quickly once first indications of demand, via sales reports, came in. In the past the franchise owners would order around two thirds of the forecasted demand for the season up front, with the remainder of the orders placed once early reaction had been received. Thousands of designs were produced annually from teams of more than 300 designers working on short-term contracts. This model was very successful and led to rapid international growth in numbers of outlets as well as unit sales, fuelled in particular by creative, and often controversial, advertising. Global distribution was, and still is, handled from a state-of-the-art distribution hub based at Castrette in Italy. Benetton and Zara both have supply chain models based upon a degree of vertical integration that allows them to exercise more control since some of the manufacturing takes place in their own factories. This differs from other international fashion retailers such as Gap, Topshop, H&M and Mango where the supply chain strategy is not to own manufacturing but to deal with independent suppliers (7). Although Benetton is widely known as an Italian manufacturer, things have changed. Benetton has relocated much of its production abroad and retains less than 20% of its manufacturing in Italy (6). The Benetton Group has clearly defined its consumer experience in terms of operational objectives as: • • • • • QUALITY RIGHT PRICE PROXIMITY TIME TO MARKET TIMELY DELIVERY (2). To achieve these objectives Benetton has set out to develop a supply chain strategy that delivers flexibility, efficiency and effectiveness in responding to the production requirements of the company. Benetton has based its supply network on two models: the Industrialised Model and the Commercial Model, each accounting for 50% of total production requirements. This approach is sometimes referred to as a dual supply chain. Benetton refers to the stores that are not wholly owned as ‘wholesale’ and these account for around 75% of the group business. The wholly owned stores which account for a further 25% of group business are referred to by the Benetton Group as Directly Managed Stores. The wholesale stores have area or regional agents who organise the orders from the individual wholesalers direct to Benetton. The store owners are, in fact, retailers in their own right but do not pay royalties to Benetton. However, they can only stock Benetton branded products and the retail pricing is controlled by Benetton. So the system operates more like a kind of franchise operation although it is strictly speaking not a franchise in the legal sense of the word. 1 Page 5 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 The Industrialised Model has higher levels of direct control and vertical integration with the Benetton Group. Production takes place in Italy, Eastern Europe, Tunisia and India. There is also significant investment in expanding production centres in Croatia and Tunisia where facilities control the complete production cycle from raw materials to finished goods. Non-vertically integrated operations in these countries handle more intensive manufacturing and finishing, which is outsourced but directly controlled by Benetton’s own production sites in Italy and other countries. Direct in-house control by Benetton is exercised over those operations that it considers ‘strategic’ in nature, such as where large scale automation is required, e.g. weaving and quality control. Significant investment has been made in automation and enhanced quality control systems. The Olympias Group, which is wholly owned by Benetton, provides textiles, yarns, clothing manufacturing, labels and laundry processes such as dyeing (garment, yarn and fabric) and finishing (stone washing jeans would be one example of this). The Commercial Model that accounts for the remaining 50% of production is outsourced to manufacturers in China, India, South-East Asia and Turkey. With this model, Benetton is seeking to maximise the benefits and lower costs of global sourcing, while maintaining rigorous control of quality and compliance, using its own locally based personnel. This double supply chain is intended to ensure efficiency and speed for Benetton’s supply operations and it uses two approaches to planning: a sequential approach aimed at minimising costs and maximising efficiency; and an integrated approach aimed at minimising response times to changes in demand. This system conducts key activities such as R&D, product design, production activities and sales in parallel (see Exhibit 1). In terms of logistics and distribution the Benetton Group has total direct control of both its Industrialised Model of direct production and the Commercial Model of outsourced production. The operations of Benetton’s distribution centre at Castrette2 are integrated with two other distribution hubs, in Asia and Latin America, which share the development of automation, modelling and organisation of the systems that have long been a feature of the Castrette operations. The IT system, which coordinates and optimises worldwide deliveries, is fully centralised and Benetton continues to invest in structures and processes (See Exhibit 2). A multinational team of more than 300 designers research feedback from stores to determine trends and consumer requirements. This is supplemented with information on customer requirements from local regional sales agents. The planning processes aim to “simplify the structure of the collections and the production processes (based on feedback received from the sales network), optimising the various operational phases to provide a constantly improved service to the point of sale” (2). The objective is to ensure rapid reaction to seasonal trends and changes in consumer demand so that the products delivered to stores are constantly updated. The Castrette platform optimises deliveries and the quality of the service to the sales network, thanks to its geographical position (close to the domestic market and the countries of Europe) and the use of innovative technologies. This structure has a fully automated electromagnetic sorting system, which can manage the individual orders of the 6,400 Benetton stores worldwide, ensuring the total integration of the production cycle. (order management, packaging and deliveries). The folded and hung garments are automatically sorted, packaged and sent through a 1km-long tunnel to the Automated Distribution Centre, which covers a 30,000 m² area, has an overall capacity of 800,000 boxes and is capable of handling 120,000 incoming and outgoing packages daily. The centre requires a workforce of only 28 people, compared to a couple of hundred people that would be necessary in a traditionally operated plant” (2). 2 Page 6 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 H&M H&M (Hennes & Mauritz) is one of the largest global fast fashion retailers. The first Hennes store opened in Vasteras, Sweden in 1947. Today it has a network of more than 3,000 H&M stores in more than 53 countries worldwide. The company continues to thrive and expand. Expansion today is focused on the USA and China as well as European markets such as Russia, Germany, the UK, Italy, Poland and France. Unlike Benetton, most of this worldwide network of retail outlets is wholly owned, with franchising playing only a small role where necessary to enter a particular market. Franchising is not seen as a core part of the development strategy long term. H&M has an intense corporate focus on sustainable practice throughout its operations and particularly with regard to supply chain operations. Quality and rapid reaction to trends also feature highly in corporate communications regarding supply side objectives. The company also strives to achieve the best possible price by: • Keeping all of the design function in-house using a team of more than 160 multinational designers and 100 pattern makers based at the company headquarters in Stockholm. • Disintermediating the supply chain – removing intermediaries and coordinating manufacturing using its own production offices and personnel in each supply market. • Achieving economies of scale by placing large volume orders. • Using global resourcing to ensure the best possible price – ‘buying the right products from the right markets’. • Efficiency in the vertically controlled logistics and distribution operations. • Maintaining a focus on costs throughout the whole organisation. H&M has concept teams comprising buyers, designers and pattern makers, which are responsible for ensuring that H&M stores keep up to date with customers and the latest trends. Highly fashionable merchandise is produced and stocked in smaller quantities in large cities. A larger volume of more basic merchandise is distributed more widely (11). To achieve the lowest possible price H&M sources from around 800 independent suppliers across Europe and Asia. Although these suppliers source the raw materials they require, H&M has extended its quality and compliance audits downstream to incorporate the mills and finishing plants that supply products and services to its suppliers. H&M’s audits also include a strong focus on environmental responsibility, sustainability and chemical management. Although H&M does not own any manufacturing it does have its own production offices and personnel in the markets where its merchandise is manufactured. These production offices are responsible for managing the timing and practical aspects of progressing orders placed, carrying out quality testing, ensuring chemical requirements are met, and conducting audits. Lead times for orders placed can vary within the supply system from a few weeks for high fashion trend items to six months for more basic high volume products. “The decision of which supplier is the right one, is not only a matter of cost-efficiency but also depends on other factors such as transport times, import quotas and quality aspects. To minimise risk, buying is carried out on an ongoing basis throughout the year. “In recent years, H&M has reduced the average lead time by 15-20% through developments in the buying process. Flexibility and short lead times diminish the risk of buying the wrong items and allow stores to restock quickly with the best-selling products” (9). Most of the goods purchased are transported by rail and sea (90%) with shops receiving goods from distribution centres in their ‘geographic vicinity’. H&M controls the inventory but outsources the transport to third parties. A large percentage of goods sold are routed to local distribution centres via a transit terminal in Germany. Page 7 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 Inditex – Zara The fast fashion chain Zara is another of the world’s largest fashion clothing retailers. It is part of the Inditex Group, a group of more than 100 companies operating in textile design, manufacturing and distribution, with headquarters in La Coruña in northern Spain. The Inditex Group has more than 6,000 retail outlets in more than 400 cities across five continents and continues to grow rapidly (15). Its fashion retail stores include Zara (1,770 shops), Zara Kids (166 shops), Pull & Bear (825 shops), Massimo Dutti (634 shops), Bershka (910 shops), Stradivarius (816 shops), Oysho (533 shops), Zara Home (363 shops) and Uterqüe (87 shops). Most of the retail outlets are wholly owned by Inditex and, similar to H&M, franchising is only used where local regulations impede direct foreign ownership. One of the unusual features of Zara is the lack of a formal marketing department and the low spend on advertising (10). Observers such as journalists and academics have therefore looked to other factors such as logistics and supply chain management for the secret to the fashion retailer’s continued success. The team of designers at Zara produce around 24,000 designs each year, out of which around one third will find their way into stores. This is significantly more designs than other fashion chains and represents a key feature of Zara’s approach to fast fashion. It ensures that the store collections or ‘product ranges’ are constantly refreshed with new merchandise. Each of the 6,000+ Inditex stores receives at least two deliveries of new merchandise every week. Regular customers shopping in Zara understand that if they see something they like they will need to buy it immediately because it is unlikely that there will be any repeat deliveries (production) of exactly the same garment. “In this way, says Masoud Golsorkhi, the editor of Tank, a London magazine about culture and fashion, Inditex has completely changed consumer behaviour. “When you went to Gucci or Chanel in October, you knew the chances were good that clothes would still be there in February,” he says. “With Zara, you know that if you don’t buy it, right then and there, within 11 days the entire stock will change. You buy it now or never. And because the prices are so low, you buy it now” (10). Communication directly from the shop floor to the production and design department in La Coruña is vital in ensuring the designers and production planners are kept up to date with customer reaction to new products, with what styles are selling and what trends are emerging. Staff in the shops contact the Zara production office to let it know what customers are asking for and if clothes with particular style features are experiencing high demand. Store staff have handheld computers to view the next order allocation and can change quantities based upon local customer preferences. Retailers essentially have two objectives. The first is to maximise return on investment in each store, by maximising sales. The second is to maximise the profitability and return on inventory for each product line. Different locations may have somewhat different demographic mixes and this will impact upon demand. Zara attempts to ensure that stores stock the optimum mix of products that appeal to particular customer requirements in each location and to maximise return on inventory in each product line by ensuring effective and accurate distribution to meet local demand characteristics. The whole of Zara’s strategy is based upon shortening lead times and reaction times to a few weeks – a quick response (QR) approach that is the retail sector equivalent of manufacturing’s JIT (Just in Time). In fact some of the factories near to Zara’s head office in La Coruña are connected to the distribution centre by an aerial monorail so that the transfer of completed garments for finishing (ironing, quality control inspection etc) is quicker and more efficient. The cutting of fabric takes place in Inditex-owned factories using the latest CAD (computer aided design) machinery and this is then sent out to a large network of small-to-medium sized sewing workshops and subcontractors. Page 8 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 Only one third of actual forecast requirement is produced ahead of the season, with the remaining two thirds produced during the season based on in-season style trends. Production is, in fact, based upon JIT principles. A substantial amount of the fabric used in Zara’s own factories is left undyed to be coloured as late as possible in the garment production cycle so that a more accurate reaction to specific local demand can be achieved (3). Half of the production for Zara comes from factories mostly owned by Inditex close to La Coruña in Spain with some also in Portugal and Morocco. The remaining 50% is produced by independent manufacturers with 30% coming from factories in Eastern European countries such as Turkey, Romania and Bulgaria, and the remainder from Vietnam, China, Brazil and Bangladesh among others (Hansen S.) where Zara can achieve 15- 20% lower production costs (3). These distant independent markets tend to be used for more basic merchandise that has a longer product life and where demand is not as volatile as the more fashionable merchandise. Zara has around 50 stores in the United States and there are limited plans for further expansion there. Zara has expanded very successfully in China where there are approximately 150 stores. Questions have been raised regarding the ability of Inditex to continue to supply China in the way it has done to date with such a large scale expansion. Doubts have been voiced as to whether the existing supply chain strategy and business model can be replicated in other distant markets (10). Nelson Fraiman, a professor at Columbia Business School who has studied the Inditex model, told the New York Times Magazine: “Their factories in La Coruña have a finite capacity to respond quickly. You open more and more stores, and you don’t have flexibility of the last-minute response. Once they have a big thrust in China, then what happens is that they will have to take the whole model” – the processing of customer reactions, the quick-turnaround design teams, the logistics platform – “and replicate it in China.” But the bigger Inditex gets, he says, the more it will lose control over quality and efficiency (10). Conclusion Fast fashion retailers are most concerned about their gross margin return on inventory (GMROI). They need to achieve a particular return on their investment in stock and as this stock is fashion clothing, the return (profit) needs to be achieved quickly. The key performance ratio GMROI is calculated in the following way: Gross Margin (on sales less VAT) Average Inventory Value at Retail Selling × 100 The lower the stock holding or inventory compared to the gross margin, the higher the GMROI becomes. This is a powerful measure considering that the main purpose of existence for a retailer is to purchase goods at one price and sell them at a higher price. So this measure informs the market on how successfully a retailer is achieving this aim – how well it is managed. Institutional investors and banks focus on this metric when making investment and financing decisions. The lower the average stockholding is compared to gross margin, the higher the GMROI will be. Shops can work on lower inventories if they have an efficient and regular delivery system. However, if sales drop, because the wrong styles or colours or size assortments are stocked, then inventory will increase. Sales promotions which reduce gross margin will need to be applied (to encourage customers to buy more of the slower moving lines) and this will mean a reduction in gross margin and, therefore, in GMROI. Having the right merchandise in stock, in exactly the right quantities, in such a fast moving and volatile global market means synchronising production, supply, distribution and deliveries to consumer demand to provide a flexible, responsive and efficient supply chain. Page 9 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 Success in the fast fashion market will, therefore, be achieved by those companies that can create and effectively manage such supply systems. Competition will, therefore, not be between retailers alone but rather between their global supply networks. This was clearly articulated in Masson et al’s (2007) published research into the complexities and challenges of managing such supply networks to achieve agility. “... the high-product variety required to succeed in this market almost always requires a significantly large and changeable supply base, so the industry is also a particularly good example of network competition (Christopher and Towill, 2000). Retailers that can successfully manage the complex supply network to achieve supply chain speed and flexibility will maximise profits when they do meet market needs, while at the same time minimising the penalties associated with missing the market” (18). With demand increasing for a smaller volume of innovative products that are introduced more frequently throughout the year there is a growing requirement for suppliers with more sophisticated production, design and operational skills. This is challenging retailers in this sector since it involves a further widening of this already complex supply structure. Page 10 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 Bibliography 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Benetton Group 2013, Downloaded on 07.11.13 from http://www.benettongroup.com/media-press/ Benetton Group Value Chain, Downloaded on 07.11.13 from http://www.benettongroup.com/valuechain/index.html Caro F., (2012), Zara; staying fast and fresh, Case Study, UCLA Anderson School of Management Christopher M., (2000), “The Agile Supply Chain; competing in volatile markets”, Industrial Marketing Management, Iss. 29, pp.37-44 Christopher M., Lowson R., Peck H., (2004) “Creating agile supply chains in the fashion industry”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Vol. 32 Iss: 8, pp.367 – 376 Christopher M., Peck H., (1997) “Managing Logistics in Fashion Markets”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol 8, No. 2, pp.63-74 Crestanello P. & Tattara G. (2009) A Global Network and its Local Ties; Restructuring of the Benetton Group, Working Paper, Department of Economics, Ca Foscari University of Venice, Downloaded on 25.10.13 from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1397103 De Brito M.P., Carbone V., Meunier Blanquart C., (2008) “Towards a sustainable retail fashion supply chain in Europe: organisation and performance”, International Journal of Production Economics Vol. 114, pp.534 - 553 E-Business Watch, Case Study: Hennes & Mauritz, downloaded on 31.10.13 from http://ec.europa. eu/enterprise/archives/e-business-watch/studies/case_studies/documents/Case%20Studies%20 2004/CS_SR01_Textile_2-HM.pdf Hansen S., How Zara Grew Into the World’s Largest Fashion Retailer, New York Times Magazine, November 9th 2012, downloaded on 13.11.2013 from, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/11/ magazine/how-zara-grew-into-the-worlds-largest-fashion-retailer.html?_r=0 H & M, AboutH&M.com, Downloaded on 24.10.13 from http://about.hm.com/en/About.html Hennes & Mauritz, Our Supply Chain, Downloaded on 31.10.13 from http://about.hm.com/en/About/ Sustainability/Commitments/Responsible-Partners/Supply-Chain.html Inditex Annual report 2012, downloaded on 24.10.13 from www.inditex.com/en/downloads/AnnualReport-Inditex-2011.pdf INDITEX Timeline, downloaded on 20.10.13 from http://www.inditex.com/en/who_we_are/timeline InditexGroup, who we are, downloaded on 08.11.13 from http://www.inditex.com/en/who_we_are/ our_group Irish Independent.ie, How fashion giant Inditex bucked trend to notch €16bn sales, 28 October 2013, Downloaded on 28.10.13 from http://www.independent.ie/business/world/how-fashion-giantinditex-bucked-trend-to-notch-16bn-sales-29704439.html MacCarthy B.L. & Jayarathne P.G.S.A., (2009) Fast Fashion; Achieving Global Quick Response (GQR) in the Internationally Dispersed Fashion Industry, Nottingham University Business School Research Paper series 2009-09 Masson R., Losif L., MacKerron G., Fernie J., (2007) “Managing complexity in agile global fashion industry supply chains”, International Journal of Logistics Management, The, Vol. 18 Iss: 2, pp.238-254 Mazaira A., González E., Avendaño R., (2003) “The role of market orientation on company performance through the development of sustainable competitive advantage: the Inditex-Zara case”, Emerald 21 Polese F., Moretta Tartaglione A., Sarno S. & Carrubbo L., (October 2009) An Efficient Value Chain, or a Service Value Network? Best practices Deriving From Zara., 2nd Annual EuroMed Conference of the EuroMed Academy of Business Managerial and Entrepreneurial Developments in the Mediterranean Area StatisticBrain.com, Fashion Industry Statistics, downloaded on 24.10.14 from http://www.statisticbrain.com/fashion-industry-statistics/ Tokatli N., (2007) “Global Sourcing Insights from the global clothing industry-the case of Zara a fast fashion retailer”, Journal of Economic Geography Tiplady R., (04,04,2006) “Zara taking the lead in fast fashion”, Bloomberg Business Week Europe Page 11 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 EXHIBITS EXHIBIT 1 – Benetton Industrial Structure Double Supply Chain EFFICIENCY SPEED Sequential Supply Chain Integrated Planning System Design Operations R&D Vs Consistency Operations R&D Design Sales Sales Benetton Group Value Chain, Downloaded on 07.11.13 from http://www.benettongroup.com/valuechain/index.html EXHIBIT 2 – Benetton Organisational Model – Operations European and Mediterranean plants Asian plants Central American plants Independent suppliers European logistics hub Asian logistics hub Central America logistics hub Italy Shenzehn Mexico City Global store network Benetton Group Value Chain, Downloaded on 07.11.13 from http://www.benettongroup.com/valuechain/index.html END OF CASE STUDY Page 12 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 BLANK PAGE Page 13 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 BLANK PAGE Page 14 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014 BLANK PAGE Page 15 of 16 AD3 Case Study May 2014