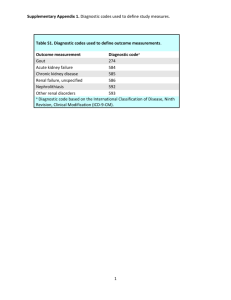

2012 American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for

advertisement